Tyrant of the year 2025: Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

A further crackdown on dissent this year continues the Supreme Leader’s bloody rule

A further crackdown on dissent this year continues the Supreme Leader’s bloody rule

Choose from our shortlist of 10 authoritarian leaders and vote on who you think has done most to crack down on freedom of expression this year

Index on Censorship has today published a new report entitled Breaking encryption is legally and practically unworkable which sets out our position on why governments should not break end-to-end encryption (E2EE).

Major service providers such as WhatsApp – which alone services 42 million users in the UK – Telegram, and Signal, use E2EE, allowing their users to securely send private messages that only they can read. E2EE works by scrambling the contents of a message into unintelligible code using a pair of cryptographic keys. In systems protected by E2EE, only the sender and the recipient hold the keys needed to decrypt the message, meaning that no one else – not even the service provider itself – can access its contents.

E2EE is an essential factor in protecting individuals and businesses from hacking, identity and personal data theft, and fraud, and it is a critical tool used by individuals for whom their safety and security depend on their communications being private and secure. This includes journalists communicating with their sources, dissidents under authoritarian regimes, human rights defenders, and victims in victim support groups.

The report builds upon years of work by Index on Censorship, parliamentarians, and independent counsel at Matrix Chambers to clearly and unequivocally demonstrate that “Technology Notices” that can be issued by Ofcom under s. 121 of the Online Safety Act 2023 (the “OSA”) are fundamentally incompatible with international and domestic human rights laws: their effect would amount to ending access to end-to-end encrypted messaging in the United Kingdom, contravening Articles 8 and 10 of the European Court of Human Rights and breaching Ofcom’s obligations under the Human Rights Act 1998, fundamentally alter the face of digital communications in the United Kingdom, and leave the UK government vulnerable to a barrage of diplomatic and international legal disputes.

At Index on Censorship, we have published censored writers across the globe since 1972. Today, we’re using encrypted messaging apps to keep in touch with our network of correspondents around the world, from Iran, to Afghanistan, to Hong Kong.

We were vindicated in raising the alarm over the government’s ongoing crusade against encryption, its potential abuse under the IPA, and we have repeatedly called for Ofcom’s power to issue Technology Notices to be removed from the OSA given their legal and practical failings.

While the OSA’s aims are commendable, the road to mass censorship is paved with good intentions, and the Government still has the chance to avoid this legal headache and practical international embarrassment.

Read the report here or flip through it below.

If you had told Sai a month ago that his latest exhibition would force him to flee across the world, he might not have been surprised.

After spending hundreds of days hiding above an interrogation centre in his home country of Myanmar, sneaking cameras illegally through military checkpoints and risking his life raising awareness about the horrors of the junta through art, he seems immune to shock.

He told Index that to get out of the country and come to Thailand in 2021, he had to “imagine himself dead”.

This experience influenced his work as an artist and curator who has become renowned for his powerful works about the trauma of political persecution and Myanmar’s military coup.

His latest Bangkok show, co-curated with his wife, is Constellation of Complicity: Visualising the Global Machine of Authoritarian Solidarity. It links his experiences with artists from around the world in a powerful exploration of how authoritarian regimes collude internationally in systems of repression. But for some, its message struck too close to home.

It opened at the end of July at the Bangkok Arts and Cultural Centre (BACC), where Sai and his wife had settled in exile. But shortly after it opened, he says that Chinese embassy officials arrived with Thai authorities and demanded that it be shut down.

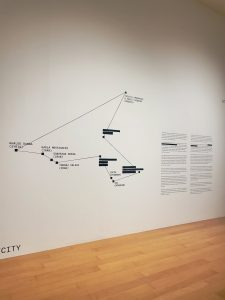

A display showing artist names which were redacted after complaints from Chinese embassy officials in Thailand. Photo: Pran Limchuenjai

A compromise was reached, but what followed was a wave of censorship that stripped the audacious exhibition of artists’ names, politically sensitive references and some of its bravest works.

The names of Uyghur artist Mukaddas Mijit, Tibetan artist Tenzin Mingyur Paldron and Hong Kong artist duo Clara Cheung and Gum Cheng Yee Man were all blacked out and their works pared down or removed entirely.

Tenzin Mingyur Paldron was the most heavily censored, with the televisions screening his video installations about the Dalai Lama and LGBTQ+ Tibetans switched off.

Tibetan and Uyghur flags were removed and a description of the censored artists’ homelands was concealed with black paint. An illustrated postcard comparing China’s treatment of Muslim populations to Israel’s was also taken down.

Sai, who goes by a single name to protect his identity after repeated warnings that he is being sought by the junta, is no stranger to state power.

His father, the former chief minister of Myanmar’s biggest state, was abducted and jailed on falsified charges after the 2021 coup. His mother lives under 24-hour surveillance, constantly fearing for her safety.

This experience has shaped both his politics and his practice. “My works usually combine social experiment with institutional critique,” he explained. “But since 2021, it has mostly been reflective of my lived experience.”

This inspired the most recent exhibition, which brings together exiled Russian, Iranian, Syrian, Burmese, Tibetan, Uyghur and Hong Kong artists. It’s a snapshot of life under repression, mapping the contours of a global authoritarian network.

“We formulated what would happen if all of the oppressed united together against the few [oppressors],” Sai explained about his defiant stance which quickly stoked retaliation.

“We were very used to absurdity, with what happened to my father, my country, my loved ones. But this was another international-level absurdity happening – the absurdity of transnational repression.”

Thailand, which Sai had once seen as a place of refuge where a large community of pro-democracy artists and dissidents from Myanmar could work with relative freedom suddenly felt perilously unsafe.

“Thailand has long tried to balance being a host for dissidents with keeping strong relations with China,” he said. “The intervention by the CCP, and Thailand’s willingness to comply with it, shows just how fragile that space really was.”

After being informed that police were looking for them, Sai and his wife booked flights out of the country. They fled within hours and are now seeking asylum in the UK.

But he is sympathetic towards the BACC. It is funded by the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, and he said it decided to censor the show due to its “connection to city authorities and the political sensitivities such as threats to diplomatic relations between Thailand and China”.

“They were under immense pressure and chose partial censorship as a way of protecting the institution,” he concluded.

However, the irony was almost too much to bear as the Chinese response handed the exhibition, which might otherwise not have been noticed, a global platform. The artists who had their names blocked out have gone viral, reaching new heights of fame. Visitors have flocked to the exhibition, while the gallery has faced uproar for its decision to bow to censorship.

Sai also says it also taught him a valuable lesson. “When we got out [of Myanmar] we promised that we would make something for our country. Now we’ve learned something – we can’t just do it for our own country, because all of these geographical boundaries are just constructs. We live in one world, and we need to fight against global repression together.”