What the world can learn from Hong Kong’s protesters

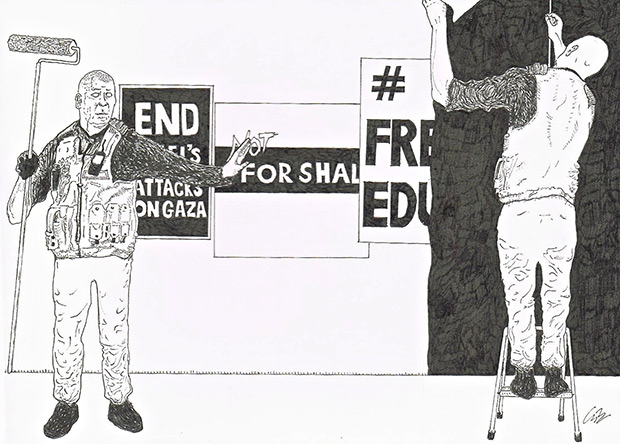

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”108932″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]The Anti-Extradition Bill Movement began with the Hong Kong government’s attempt to amend the extradition bill, which would allow people residing in Hong Kong to be extradited to and tried in the mainland China. Within months, the protest developed into a massive and sustained movement. In one of the many marches, two million Hong Kongers showed up. Protesters also extended their goals and demanded the government investigate police brutality, drop charges against protesters who had been arrested, and implement democratic reform.

Scholars, commentators, and international observers alike are all stunned by the movement. We, common Hong Kongers, are also surprised by our own actions.

We have not achieved our goals yet, so it may sound overconfident to say that protesters worldwide can draw lessons from us. However, this movement grew out of a period of abeyance following the 2014 Umbrella Movement. We may not be able to tell others how to win a battle, but people can learn from us on how to mobilise and how to sustain a mobilisation.

Lesson One

Be tolerant to your fellow protesters who do not strictly share your tactical principles or ideologies.

The Umbrella Movement ended with a split within the opposition camp. Pan-democrats and traditional left-leaning movement groups split with localists, and militants engaged in heated and sometimes toxic verbal quarrels with pacifists and moderates. Social media such as Facebook magnified the mutual resentment. It was very demoralising.

The current movement sees a curious reengagement between militants and moderates. One major reason, of course, is that the government has become more oppressive. Blatant police brutality naturally unites people of all ideologies. Yet, we should also attribute the maintenance of unity to protesters’ willingness to learn from each other and to tolerate differences.

We may already have forgotten, but the first major resistance against the extradition bill was not on the streets. It was within the legislature. Pan-democratic lawmakers, many of whom were not comfortable with physical conflicts, made a “leap of faith” and became more militant. They filibustered, occupied chambers, surrounded a pro-Beijing lawmaker who tried to illegitimately chair the bill’s committee, and clashed with security officers. Their willingness to break some taboos earned them certain recognition from radicals and militants.

The first major test of unity came when militant protesters stormed into the legislature on 1 July, the anniversary of the handover of Hong Kong to China. The breaking of windows and vandalism could have easily alienated moderates. Yet, the militants tried hard to explain their action to seek understanding, and professed a strong sense of determination. Moderates, including the pan-dems, decided to not sever ties with them.

Another trial came when the controversial brawl at the airport broke out. The tying up of a reporter from the Global Times, who protesters believed was an undercover police officer from China, was certainly quite hard for moderates to swallow. However, some militants apologised the next day, providing moderates with the space to continue to stay united.

While radical militants repeatedly attacked police stations, moderates have so far tried to understand their anger and rejected the government’s accusation of riots. When moderates held a massive march the weekend after the airport demonstration, militants, despite believing that peaceful tactics were “useless,” joined in.

This unity is, of course, far from perfect. Moderates and militants continue to exchange strongly worded jibes and critiques. But both sides are more willing than before to cross the aisle. The classical tactic employed by the Chinese Communist Party to quell dissidents is the “united front”: unite with secondary enemies while attacking the major ones. In some sense, Hong Kong protesters have finally adopted this principle. Tactical and ideological differences are secondary, the primary enemy is the government. If the CCP wants to divide and destroy, then we need to unite and resist.

Lesson Two

Be water, be creative, and be humble.

“Be water” is probably the highest principle of mobilisation in this movement. The idea comes from the martial artist and film star Bruce Lee: “Be formless, shapeless, like water… Water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend.” The point is to reject any form of tactical formalism.

During the Umbrella Movement, one of the major difficulties that occupants faced was that it was very costly to maintain an occupied area. It required a sustained flow of resources, a continuous presence of a critical number of occupants, and constant alert over police attack. Contentious action is tiring. Rest is much needed.

This time, protesters have adopted a repeated pattern of “march, attack and rest”: taking action (peaceful or militant) on a weekend, go home and then come out on the streets again next week.

A sustained and prolonged movement is very tiring. Creativity helps. Newness of action encourages people to fight on. The repertoire of tactics has expanded rapidly in this movement. The “traditional” marching route begins in Victoria Park on Hong Kong Island, and ends at the government headquarters. All three million-strong marches roughly followed this route. Yet, protesters have taken an unprecedented step: holding marches and assemblies all over Hong Kong.

When I joined the march on the streets of Kowloon in July, the experience was refreshing. I never imagined I could walk on roads outside the iconic Peninsular Hotel. Sometimes a new action can be very random. When the police violently arrested a student for buying laser pointers, and accused him of possessing “offensive weapons”, people were outraged. Some angry protesters surrounded the police station and were later dispersed by tear gas. On another night, protesters held a “stargazing assembly” outside the Space Museum. All the participants brought laser pointers along. It turned into “a symphony of lights” and, eventually, a dance party.

Hong Kongers are also humble enough to learn from foreign examples. In 2014, protesters imitated the Lennon Wall in Prague and made up one of their own at the occupied zone with colorful postscripts. This time, Lennon Walls sprang up everywhere. The one near the Tai Po Market subway station developed into a spectacular “Lennon Tunnel.” And on 23 August, the 30th anniversary of the Baltic Way, when a human chain stretched across the Baltics in opposition to Soviet rule, we gathered together and built our Hong Kong Way.

Scholars of social movements such as Sidney Tarrow have long been studying how movement tactics diffuse. Some tactics are modular, meaning that they are prevalent and adaptable to new settings. Yet, each specific action also has to resonate with local cultures in order to be effective and affective. In this sense, Hong Kongers “indigenised” both the Lennon Wall and the Baltic Way.

The Hong Kong Way is especially telling. Protesters formed human chains modelling three major subway lines. Moreover, one chain extended onto the symbolic Lion Rock and participants lit it up with cell phone flashlights. When protesters hung a huge yellow banner on that hill in 2014, the “Lion Rock Spirit,” which originally represented economic development, was redefined to a spirit for democracy. The spirit was redefined again by the Hong Kong Way, professing unity, persistence and hope in the face of oppression and darkness. Others far away can learn from us, just as we have learned from those far away from us in space and time

Lesson Three

Stand up to bullies.

When kids are bullied, we teach them to stand up. Retreat or concession will only embolden the bullies. But, when it comes to politics, we seem to quickly come up with the conclusion that “politics is the art of compromise”. It is very common to hear people saying: “Beijing is too strong, don’t oppose it.” “We can gain so much by befriending China, what is the point of becoming its enemies?” But condoning bullies always has consequences. We all know that.

When the Hong Kong government first introduced the proposed extradition amendments, many believed that there was no way to stop the legislation process. The almighty Beijing was behind Carrie Lam, the chief executive of Hong Kong, and civil society was suffering from demobilisation after 2014. The first march against the bill was so small and seemingly insignificant that no one paid serious attention to it. Lam and her colleagues were emboldened, and belittled all opposition voices, including those from the legal sector. People were outraged, and momentum was built up step by step. Our mobilisation eventually forced Lam to suspend the bill (though we are demanding a complete withdrawal).

We still do not know whether we will come out victorious. But we know that we have to fight on. For if we concede now, we will suffer from serious consequences.

Hong Kong’s aviation industry is probably one of the most progressive sectors in the city. Beijing was not happy when a small number of pilots and cabin crew voiced support for the protests. The CCP pressurised the airlines to take action. The biggest Cathay Pacific, owned by conglomerate Swire, launched a heavy crackdown against its own managers and employees to kowtow to Beijing. The reason for surrendering, of course, is the company’s heavy reliance on China’s market and airspace. By conceding to bullying, Cathay Pacific not only lost Hong Kongers’ support, but also allowed Beijing to further step up its repression. Hong Kong cannot become another Cathay.

The fight against the extradition bill is Hong Kong’s battle against Beijing’s bullying. We have conceded so much in recent years that we have learned that, in fact, concession will only invite more intrusive oppression, and even violence. This is not to say that one can start an outright war with a bully without assessing one’s own costs and benefits. Yet, principled self-defense is always necessary. If you do not stand up, no one will stand up for you.

Be water, my friend. Also, be brave and be principled.[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1567590823109-829eac1b-4d0e-1″ taxonomies=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]