22 Sep 2020 | Art and the Law, Free Speech and the Law, Hate Speech, Index in the Press, News and features, Statements, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114965″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Heavy fines for social media companies who fail to act on online abuse and hate speech will have a negative effect on online expression, according to Index on Censorship CEO Ruth Smeeth.

Smeeth was taking part in a discussion on the proposed Online Harms Bill with the Board of Deputies of British Jews, a group that acts as a forum for members of the country’s Jewish community, along with shadow home secretary Nick Thomas-Symonds and Tottenham MP David Lammy (see top).

“Self-regulation has not really been effective,” said Smeeth. “[But] if we fine heavily they will be so conservative with what they allow on the platform.”

The discussion was called after rising incidence of anti-Semitism in the UK. Between January and June, 789 separate incidents of anti-Semitism were logged, up 4% on the previous year.

The proposed Online Harms Bill – still in its white paper stage – aims to force social media companies to regulate their sites in order to clamp down on abuse and harmful speech. The legislation is in line with a similar ruling in Germany introduced in 2017, where social media companies can face fines of up to €50 million.

Smeeth, herself a victim of online abuse, expressed her support for the bill as a way of tackling illegal hate speech, but suggested that alterations need to be made so that overly heavy fines do not cause social media companies to over-regulate.

“There are young people who have not been able to access counselling services having self-harmed,” she said. “They are using online forums to talk about their pain sometimes in very explicit language to support groups.”

“They would not be able to do so under this legislation.”

Clause 3.5 of the white paper draft will ensure that not just illegal hate speech can be shut down, but also what the legislation deems ‘legal but harmful’.

“The idea that we have something that is legal on the street but illegal on social media makes very little sense to me,” she said.

In 2019, Index made a submission to the white paper consultation, stating: “The focus on the catch-all term of ‘harms’ tends to oversimplify the issues. Not all harms need a legislative response.”

The law in Germany has since been criticised by Human Rights Watch and said it sets a precedent that will turn private companies into ‘overzealous censors’.

Shadow home secretary Thomas-Symonds is keen to have an independent regulator and feels the time for self-regulation has ‘long passed’.

He said: “We need a statutory duty of care and an independent regulator that has teeth. It has to have that power to levy particular penalties when social media companies are simply not doing what they should be.”

Lammy added that the key to curbing online hate speech towards minorities and anti-Semitism was the Online Harms Bill.

“You are not a civilised democracy if you do not protect minorities,” he said. “Until we have dealt with this issue nationally, we will not have fully dealt with it.”

In June, Lord Puttnam – Chair of the Lords Democracy and Digital Committee – warned that the bill may not come into effect until late 2023 or early 2024.

The full Index issued response to the white paper can be read here.

[/vc_column_text][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”38952″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Feb 2016 | Academic Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, Poland

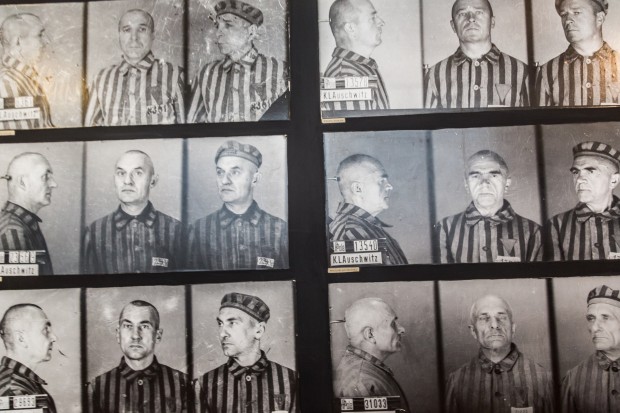

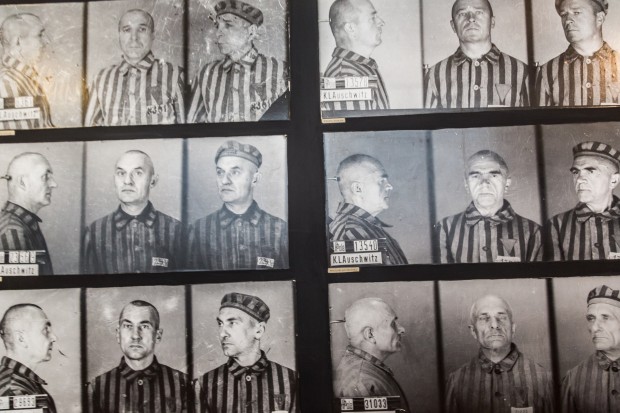

Still from an Auschwitz exhibition, 22 July 2014 in Oswiecim, Poland

When discussing academic freedom more than a century ago, German sociologist and philosopher Max Weber wrote: “The first task of a competent teacher is to teach his students to acknowledge inconvenient facts.” In Poland today, history appears to be an inconvenience for the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, which is introducing legislation to punish the use of the term “Polish death camps”.

The Polish justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro announced earlier this month that the use of the phrase in reference to wartime Nazi concentration camps in Poland could now be punishable with up to five years in prison. If enacted, Poland would find itself in the unique position of being a country where both denying and discussing the Holocaust could land you in trouble with the law. Holocaust denial has been outlawed in Poland — under punishment of three years “deprivation of liberty” — since 1998.

Any suggestion of Polish complicity in Nazi war crimes against Jews brings with it, in the party’s own words, a “humiliation of the Polish nation”.

Of course, Poland was an occupied country which suffered terribly under Nazi Germany, so any talk of acquiescence understandably hits a nerve. As all good history students know, however, the discipline has its ambiguities and competing theories, from the acclaimed to the crackpot, and singular, simplistic narratives are rare. But few democratic countries in the world punish those who argue unpopular historical positions. Which is why legislating against uneasy truths is the same as legislating against academic freedom.

Two recent examples show the Polish government of doing just this. Firstly, Poland’s President Andrzej Duda made public his serious consideration to stripping the Polish-American Princeton professor of history at Princeton University Jan Gross of an Order of Merit — which he received in 1996 both for activities as a dissident in communist Poland in the 1960s and for his scholarship — over his academic work on Polish anti-Semitism. Gross outlined in his 2001 book Neighbors that the massacre of some 1,600 Jews from the Polish village of Jedwabne in July 1941 was committed by Poles, not Nazis. More recently, the historian has claimed that Poles killed more Jews than they did Germans during the war, which prompted the current action against him.

Some who disagree with his arguments have labelled Gross an “enemy” of Poland and a “traitor to the motherland”. The historian has hit back, saying in an interview with the Associated Press: “They want to take [the Order of Merit] away from me for saying what a right-wing, nationalist, xenophobic segment of the population refuses to recognise as facts of history.”

Academics too — Polish and otherwise — have come to his defence. Agata Bielik-Robson, professor of Jewish Studies at Nottingham University, points out that a “democracy has to have a voice of inner criticism”. She is worried that PiS is seeking to do away with such criticism in order “to produce a uniform historical perspective”.

Polish journalist and former activist in the anti-communist Polish trade union Solidarity Konstanty Gebert explained to Index on Censorship that PiS has made “convenient scapegoats” of people like Gross. “PiS is moving fast to reestablish a ‘positive narrative of Polish history’ by breaking with an alleged ‘pedagogy of shame’,” he said.

The party first tried — unsuccessfully — to outlaw the term “Polish death camps” in 2013 when it was in opposition. Should the law now pass, and you need help adhering to the proposed rules, the Auschwitz Museum has released an app to correct any “memory errors” you may experience. It detects thought crimes such as the words “Polish concentration camp” in 16 different languages on your computer, keeping you on the right track with prompts asking if you instead meant to write “German concentration camp”.

Poland may have lurched to the right with the election of PiS last October, but the party’s authoritarianism — from crackdowns on the media to moves to take control of the supreme court — seems positively Soviet in some respects. Attempts to control history, too hark back to the Polish People’s Republic of 1945-1989, when, in the words of Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier in the winter 1985 issue of Slavic Review, “cultural patterns” and “habits of mind” made it impossible to make historical interpretations “alien to that national sense of identity and a methodology at odds with the canons and objective scholarship”.

Gebert sees similarities between current and communist-era propaganda “in the basic formulation that there is nothing to be ashamed of in Polish history, and in Polish-Jewish relations in particular, and in the belief that there is one correct national viewpoint”.

However, now that freedom of speech exists, the government can and are being criticised for their actions. “This puts the government propaganda machine on the defensive,” Gebert said.

Just last week, President Duda spoke against the “defamation” of the Polish people “through the hypocrisy of history and the creation of facts that never took place”. He has made his motives clear: “Today, our great responsibility to create a framework […] with the dual aim of fostering a greater sense of patriotic pride at home while enhancing the country’s image abroad.”

It should be intolerable for the freedoms of any academic subject to be impinged for ideological ends. If academic freedom is to mean anything, it should include the right to tell uneasy truths, get things wrong and have you work challenged by the highest academic standards.

There’s only one place to turn for PiS to find an example of best practice on how to challenge Gross’ research, and that is to the very body the party will grant authority to on deciding on what is and isn’t a breach of the law regarding “Polish death camps”. Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) produced several reports between 2000-03 challenging claims in Gross’ book on the Jedwabne massacre. It used research and reason — as opposed to censorship — to make the case that the historian didn’t get all the facts right. It found, for example, that German’s played a bigger part in the slaughter than Gross had claimed, and that the numbers killed were more likely to be around the 340 mark, rather than 1,600.

IPN should tread carefully, though. Any inconvenient truths with the potential to humiliate the Polish people could one day soon see it branded a “traitor”.

Ryan McChrystal is the assistant editor, online at Index on Censorship

2 Jul 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

It is probably a sign of the success of our society that people like me spend so much of our time defending the rights of jerks.

Racists, misogynists, Christian fundamentalists, jihadists, wannabe jihadists, counter-jihadists, homophobes, trolls, Top Gear presenters, True Torah Jews, Nazis; cretins of all colours and creeds. In modern, liberal Europe, these are the people who tend to get in trouble over free speech. In the past, they were the ones in charge.

That is not to say everyone else is entirely free from censorship; and of course, the reason we defend free expression as a good in itself is because we understand that the powers used to silence the craven can also be used to silence the virtuous, but by and large, it’s the oddballs who tend to get into trouble. Them and journalists.

And so we turn our attention, wearily but determinedly, to the case of the “anti-Jewification” protest which was due to take place in London’s Golders Green on 4 July. As others have pointed out, anyone hoping to prevent the “Jewification” of Golders Green is, frankly, a bit late. But then, we know full well that Judenfrei policies have experienced some success in the past.

The stationary protest will now not take place in Golders Green, but instead in central London – Whitehall to be precise, away from Golders Green’s Jewish community. Ironically, many Jews are now planning to make their way to Westminster to stage a counter-demonstration.

As Richard Ferrer, editor of Jewish News, noted: “Saturday’s rally is fast turning into the social event of the season for the capital’s Jewish community. When it was originally announced, synagogues braced themselves for their lowest Shabbat attendance figures in years. I had a family lunch booked, but had to make sure it didn’t clash with the scheduled Holocaust denial and book burning.”

It does all sound rather fun, but the moving of the Nazi demonstration does raise questions about the nature of protest and how it is policed.

A demonstration must be disruptive, by its very nature. So there’s a dilemma raised by the moving of a protest from the scene of its target, in this case the Jewish community, does it become effectively meaningless? What happens if a swastika waves in a side street in Whitehall, with no one there to fear it? Does it still resound?

The police decision to move the demonstration, in spite of earlier claims that they were powerless to do so, has effectively neutered it. It’s meaningless.

Now here’s the question: should the police have a right to neuter protest in that manner? Or does the fact that the neo-Nazis are allowed stand in the street and make their little speeches, even if it’s not the street they wanted to stand in, mean that their free speech has been fully protected? I’m not entirely sure we’ve thought about this fully. But I do recall past campaigns against “designated protest zones”, for example during the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

I don’t really know what the answer is here: I guess the simple point is that one should be free to protest outside institutions but not outside people’s homes. But then what about the UK Uncut protesters who staged a “street party” outside then-Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg’s home?

This case of the relocated anti-Semites is interesting exactly because it has not turned out to be Britain’s Skokie case. To briefly recap, Skokie was an Illinois town where many Holocaust survivors had settled.

In 1977, the National Socialist Party of America proposed a march there. They were opposed. The case eventually ended up in the Supreme Court. The ACLU backed the Nazis’ right to march. Eventually, the court upheld the Nazis’ right to march. But they never actually did. [For more on this case, read Index on Censorship magazine, Vol 37, Number 3, 2008].

In 2015 in north London we have a similar but different case. There are some Nazis wanting to march in a Jewish neighbourhood, there are some people who object. But there is no great call to principle, no great desire to take up the cause seemingly on either side. It’s hard to even get anyone on the Nazi side to own up to who exactly is in charge. Joshua Bonehill, the Somerset Stormtrooper and all round troll, is widely believed to be responsible. He was arrested early this week on suspicion of incitement to racial hatred. No one seemed that bothered.

This is the British way of free expression; a matter of practicality rather than principle, a pliable concept, one that can almost always be tempered by appeals to taste: it is simply distasteful for Nazis to demonstrate in Golders Green; just not done to burn a poppy.

By and large, taste wins out in these compromises. Remember that the Chatterley ban only came to an end because it was deemed that the book was of high enough literary quality, not because adults have the right to read what they damned well please.

Tastefulness being the characteristic the British most pride themselves upon means it’s rare that anyone will argue against it. It’s a soft tyranny most people seem happy to live with.

This article was posted on 2 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Feb 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

Should we be worried about anti-Semitism in the United Kingdom? Wrong question. We should always be worried about anti-Semitism. There is no point at which we can relax about anti-Semitism in the UK. Should we be more worried about anti-Semitism in the UK?

Probably.

Britain’s All Party Parliamentary Group on Antisemitism has just released a report that unequivocally tells us we should be. The list of incidents in the UK that could reasonably be described as anti-Semitic is discouraging reading. Some are tied to the Israel/Hamas conflict, some are not. Some come under the cover of “legitimate criticism of Israel”, some do not bother to wear that cloak.

What does it mean to boycott an Israeli theatre production? Or to tell a Jewish film festival it cannot take money from the Israeli government? On a superficial level, it is, of course, nothing more than a simple stand against militarism, in solidarity with oppressed Palestinians. Of course. Jewishness has nothing to do with anything; though, you’d think, with their history, they’d know better. Better than persecuting others; better than standing out and blending in simultaneously, confusingly; better than once again bringing down wrath upon themselves.

And suddenly it’s all about Jewishness. And that’s how we get so quickly from picketing plays to supermarkets hiding kosher products for fear of vandalism.

And then there is the simple, straightforward, hatred: an attack on a north London kosher cafe; a Holocaust Memorial Day poster daubed with the word “liars”. A proposed Nazi march on a Jewish neighbourhood.

Anti-Jewish bigotry is not alone in this complexity: too often, too easily, criticism of political Islamism, or jihadist violence, spills into discrimination against Muslims. In the United States, and in Britain, “counter-jihad” really means “anti-Muslim”. Populist parties suddenly present themselves as deeply concerned about animal welfare in halal slaughterhouses, or even women’s rights, when it gives them a chance to make Muslims feel uncomfortable.

But this is not a competition, a race to find which people are more oppressed. Too often, concerns about anti-Semitism are shrugged off because Jews are perceived as, by and large, “comfortable”. This is to ignore how quickly such “comfort” can be upended, and has been in the past. And as if assumed financial status wasn’t a classic component of anti-Semitism in the first place.

The worry that little has really changed, and things may in fact be getting worse, is borne out in the All Party Parliamentary Group on Antisemitism’s paragraph on social media. To quote the report, which covers August to November 2014:

Tweets that read (sic): “The Jews now are worse than they were in Hitler’s time no wonder he wanted to get rid, right idea!!”, “If anyone still believes jews have a “right” to exist on this planet, you are a f****** moron” and “Somhow bring back Hitler.. Just for once to finish off the job he startd & show the Muslim world how to do it”

• Pictures shared on Twitter of individuals with waxworks of Hitler and accompanying antisemitic messages

• Antisemitic imagery such as that sent to Luciana Berger MP (for which the perpetrator was later prosecuted)

• An antisemitic trope about Jewish control of politicians referenced by a BBC journalist

• The presence of Hitlerian themes and imagery on Facebook comment chains for pro-Palestinian demonstrations, organised by groups such as Palestine Solidarity Campaign, Stop the War Coalition and Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

So far, so familiar: at this stage it’s barely even worth pointing out that anti-Semitic comments were found on left-wing Facebook pages. We’ve seen how it works.

Can anything be done to change this? The APPG suggests that the Crown Prosecution Service examines the possibility of “prevention orders” (“internet ASBOs”, as they have been dubbed by the press), which would ban people expressing anti-Semitic views from posting on certain social media sites. The group expresses “limited” sympathy for social media providers in their efforts to control hate speech on their platforms, given the volume of content posted every day, while suggesting a greater role for prosecutors.

But will it really help to simply kick these people off Twitter? Bigotry existed and thrived long before the internet. It would be lazy to imagine that the best way to stop a phenomenon which sometimes manifests itself on the web would be to ban it from the web itself: that way lies complacency.

Three weeks ago, I attended the official Holocaust Memorial Day commemoration at Westminster Central Hall. There, to his credit, David Cameron told Holocaust survivors of the government’s plans to fund a Holocaust Learning Centre and a permanent memorial. Many of the remaining survivors of the Holocaust have spent their old age travelling the country, talking and talking and talking, telling the world. They understand that the only hope we have to stop a repeat of what happened is to keep on talking, to pass on the stories, to ensure no one has an excuse for ignorance about what they went through.

The risk with attempting to ban anti-Semitic language is that the ban becomes bigger than the counterspeech. The ban consumes, while the story fades. And if the story fades, the bigots can rebuild, this time on their terms, high on resentment and low on truth.

This article was posted on 12 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org