26 Jul 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Screenshot from Mona el-Mazbouh’s apology video.

The below signatories express grave concern for the status of free speech and expression in Egypt. The authorities continue to openly silence anyone who is critical of the Egyptian government and of the state of affairs in Egypt. The arrest of Lebanese tourist Mona el-Mazbouh last month is yet another episode in President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s continued crackdown on rights and freedoms. We call for the immediate and unconditional release of Mona el-Mazbouh, who was sentenced to eight years in prison earlier this month.

Background

Lebanese Mona el-Mazbouh, 24, posted a 10-minute video to her Facebook account in May after she was allegedly sexually harassed, a lived reality that is experienced on a daily basis by most women in Egypt. The video included profanity against Egypt and Egyptians. Mona was stopped and arrested on 31 May at Cairo airport before leaving Egypt, after her video went viral on social media. Egyptian lawyer Amr Abdelsalam had filed a report against her with the general prosecution, accusing her of insulting the Egyptian people and the president. Abdelsalam has asked that she be added to the scores of Egyptians barred from leaving the country while her case remains open and until her sentence is completed, and to later permanently prevent her from entering the country.

The Egyptian attorney general ordered the immediate referral of Mona to an expedited criminal trial on 3 June for insulting the Egyptian people on social media. The prosecution accused Mona of “spreading false rumours that aim to harm society and defame religions, as well as creating inappropriate content and displaying it through her Facebook page”.

A Cairo misdemeanours court sentenced Mona to eight years in prison on 7 July for publishing a video with indecent content, defaming religion, insulting the Egyptian people and insulting the president. She was also fined EGP10,700 (around $598 USD).

Draconian laws that curtail free expression in Egypt

Accusations such as insulting the Egyptian people or the president are a serious transgression of the right to freedom of expression, which is guaranteed and protected by the Egyptian constitution and international human rights law. Over the past two years, there have been rapid and disturbing developments concerning the closure of physical and digital public spaces in Egypt, and an increased surveillance of social media and digital content.

A few weeks before Mona’s arrest, on 11 May, Egyptian activist Amal Fathy was arrested two days after she posted a video on Facebook condemning sexual harassment and disapproving of the government’s negligence on the issue. Fathy was charged with “disseminating a video on social media to publicly incite overthrowing the government”, “publishing a video that includes false news that could harm public peace”, and “misusing telecommunication tools”.

In addition, the Egyptian government continues to draft and approve laws that significantly curtail freedom of expression online, while heightening surveillance and censorship of social media users. On 5 June, Parliament approved the final draft of the new Cybercrime Law, titled “the Law on Combating Cybercrimes” that legalises broad censorship of the internet and facilitates comprehensive surveillance of communications.

Most recently, Parliament also approved a final reading a bill allowing authorities to monitor social media users and combat “fake news”, whereby individuals whose social media accounts have more than 5,000 followers could be placed under the supervision of Egypt’s Supreme Council for Media Regulations.

These developments reinforce the troubling and ongoing trend in Egypt of silencing public discourse and shrinking civic space that has now led to Mona’s arrest and detention.

Urgent action required

Before her arrest, Mona published a second video addressing the public response she received for the first. In her second video, Mona apologised for the content of the first, and clarified that she was not making a political statement and did not mention the Egyptian President at all in her initial video.

She was initially sentenced to 11 years in prison, however, her sentence was reduced to eight years after her lawyer provided the court with evidence that she “underwent a surgery in 2006 to remove a blood clot from her brain, which has impaired her ability to control anger”. Mona awaits her appeal date set for 29 July.

The below signatories believe that Mona el-Mazbouh’s arrest is a violation of her basic rights and freedoms, and connotes an even bigger threat to the general state of free expression in Egypt. We demand the immediate and unconditional release of Mona el-Mazbouh, and request that all charges be dropped allowing Mona to leave and enter Egypt freely.

Signed,

Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE)

7amleh – Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media

Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

Africa Freedom of Information Centre (AFIC)

Article 19

Association of Caribbean Media Workers

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS)

Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI)

Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)

Freedom Forum

Human Rights Network for Journalists – Uganda (HRNJ-Uganda)

I’lam Arab Center for Media Freedom Development and Research

Independent Journalism Center (IJC)

Index on Censorship

Maharat Foundation

March

Mediacentar Sarajevo

Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA)

Pacific Islands News Association (PINA)

Pen American Center

Pen Canada

Social Media Exchange (SMEX)

South East Europe Media Organisation

Vigilance for Democracy and the Civic State

Visualizing Impact (VI)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1532684122469-2df2f596-084e-2″ taxonomies=”147″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Jun 2018 | Global Journalist, Media Freedom, News and features, Zimbabwe

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published interviews with exiled journalists from around the world.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”100854″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Georgina Godwin grew up in a country at war.

Born to a liberal white family in what was then Rhodesia in the late 1960s, she lived through an era of atrocities as the white-minority government of President Ian Smith battled rebels from Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army. An older brother Peter, now a journalist and author, was conscripted to fight the rebels in the British South Africa Police. An older sister, Jain, was killed in 1978 when she and her fiancé drove into an army ambush.

After white-rule ended in 1980 and Mugabe won election as prime minister in what was now Zimbabwe, some whites left the country. Godwin stayed and became a well-known DJ on state-owned radio, later hosting the morning television program “AMZimbabwe” for the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corp.

By the late 1990s, that position was more and more uncomfortable. Mugabe’s government had become increasingly authoritarian and corrupt. An opposition movement led by trade unionists and backed by some whites began to grow, and Godwin felt herself increasingly drawn to opposition politics.”It felt irresponsible to be in a public position and not say or do anything,” Godwin says, in an interview with Global Journalist.

When a group of friends told her they planned to go to court to challenge the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corp.’s monopoly of the country’s airwaves, she offered to help them start the country’s first independent radio station if they won.

In a surprise decision in 2000, the Zimbabwe Supreme Court allowed the station to go forward.

“While I was on air, getting the weather update, chatting about music, the phone call came through from the court – they have actually won the case,” she says. “I continued the show and at the end I signed off. I resigned on air and said ‘I’m really sorry, this will be my last broadcast with the Zimbabwean Broadcasting Corporation.’ I couldn’t say where I was going next because it was a secret. At that point, we didn’t know really how we were going to set it up [the radio station] or what we were going to do.”

The short-lived Capital FM began broadcasting soon afterwards from a transmitter atop a hotel roof in Harare. Within a week, Mugabe, then president, issued decree closing the station, and soldiers raided Capital FM’s studio, destroying its equipment.

In 2001, Godwin moved to London, where the founders of Capital FM set up a station called SW Africa Radio to broadcast news and information back to Zimbabwe via shortwave. Zimbabwe’s government declared her and her colleagues “enemies of the state.” Return trips to the country, where her elderly parents still lived, became increasingly nerve-wracking.

Godwin spent several years with SW Africa Radio before becoming a freelance journalist and working for a number of British news outlets. Currently, she is books editor for Monocle 24, the online radio station of Monocle magazine. She hosts the literary program “Meet the Writers” and frequently appears on Monocle 24’s current affairs shows.

Godwin spoke with Global Journalist’s Teodora Agarici about her exile from Zimbabwe and her feelings about the Zimbabwe military’s ouster of Mugabe last year. Below, an edited version of their interview:

Global Journalist: How difficult was it for you to adapt to life in the United Kingdom?

Godwin: Adapting has been really interesting. I look like the majority of British people, I’m white and I don’t have a particularly strong accent, so people look at me and they think I’m British.

But when I first arrived here, I had no understanding of how the underground network worked, the kind of cultural and historical things that people have all grown up watching on television, not even the huge class divide that you find here.

I think, particularly after Brexit, I’m very aware of the fact that I am not British, but I am a Londoner. Being in London means that we’re part of the city, but that doesn’t mean we’re British and certainly doesn’t mean that we’re part of the people who chose to really turn inward and reject the rest of the world as they did with the Brexit vote.

GJ: How do you assess press freedom in Zimbabwe now?

Godwin: Some of the old people who were writing very brave stories, they’re still carrying on. We need to salute those people who did it through the bad times when newspaper offices were being bombed, when journalists were being disappeared and beaten up.

I think it’s easier now and people do feel more emboldened to speak out and say what is going on. I’d be very interested to see in the run-up to the [July 2018] election how much they are actually allowed to say, but I think that there are some incredible journalists and correspondents doing excellent work at some cost to themselves.

As for how foreign media covers Zimbabwe, people do have a genuine choice. The internet exists, independent newspapers are publishing, and then there are all the international stations like al-Jazeera, the BBC and South African stations.

GJ: Mugabe’s former vice president Emmerson Mnangagwa is now president. He was minister of state security in the 1980s, when the security services killed up to 20,000 civilians. Do you think it’s safe for you to return now?

Godwin: I’d been there twice since I left, both times under a different passport that I no longer have access to. Because I was on television, it doesn’t really matter what names are in your passport. People recognise you from TV.

You’re basically relying on the goodwill of the immigration officer and you just have to hope that he’s not somebody that was aware of what you’ve done before or if they were aware, it was something that they approved of.

As my brother writes in one of his memoirs, he went in and the immigration officer asked, “Are you related to Georgina?”

I think he tried not to reply, but the officer quietly said, “Please tell her we listen to her every day.”

The question is now, under the change of government, would I be welcome? I’m still being outspoken about what I think. I have no personal animosity towards [President] Emmerson Mnangagwa, but I do believe what was done under his watch was absolutely criminal. It was genocide.

I’m not sure that he would welcome me into what is effectively his country at this point. But I have such wonderful optimism for the country. We’re at a time now where Zimbabweans have a real choice and I hope that what they do is not dictated by history and they don’t just vote because they’ve always been for [the ruling party] ZANU–PF.

The next generation has got something to offer and take us in a different direction. So many Zimbabweans have been suffering under the regime and finally, everybody can enjoy the fruits of the labour, of the people who fought so hard, not just the journalists, not just my colleagues, but all of the everyday people who have just fought so hard against the the deep, uncaring corruption and the people that are in charge of them.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/tOxGaGKy6fo”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook). We’ll send you our weekly newsletter, our monthly events update and periodic updates about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share, sell or transfer your personal information to anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Nov 2017 | Digital Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Facebook has received much criticism recently around the removal of content and its lack of transparency as to the reasons why. Although it maintains their right as a private company to remove content that violates community guidelines, many critics claim this disproportionately targets marginalised people and groups. A report by ProPublica in June 2017 found that Facebook’s secret censorship policies “tend to favour elites and governments over grassroots activists and racial minorities”.

The company claims in their community standards that they don’t censor posts that are newsworthy or raise awareness, but this clearly isn’t always the case.

The Rohingya people

Most recently, almost a year after the human rights groups’ letter, Facebook has continuously censored content related to the Rohingya people, a stateless minority who mostly reside in Burma. Rohingya have repeatedly been banned from Facebook for posting about atrocities committed against them. The story resurfaced amid claims that Rohingya people will be offered sterilisation in refugee camps.

Refugees have used Facebook as a tool to document the accounts of ethnic cleansing against their communities in refugee camps and Burma’s conflict zone, the Rakhine State. These areas range from difficult to impossible to be reached by reporters, making first-hand accounts so important.

Rohingya activists told the Daily Beast that their accounts are frequently taken down or suspended when they post about their persecution by the Burmese military.

Dakota Access Pipeline protesters

In September 2016 Facebook admitted removing a live video posted by anti-Dakota Access Pipeline activists in the USA. The video showed police arresting around two dozen protesters, although after the link was shared access was denied to viewers.

Facebook blamed their automated spam filter for censoring the video, a feature that is often criticised for being vague and secretive.

Palestinian journalists

In the same month as the Dakota Access Pipeline video, Facebook suspended the accounts of editors from two Palestinian news publications based in the occupied West Bank without providing a reason. There are no reports of the journalists violating the networking site’s community standards, but the editors allege their pages may have been censored because of a recent agreement between the US social media giant and the Israeli government aimed at tackling posts inciting violence.

Facebook later released a statement which stated: “Our team processes millions of reports each week, and we sometimes get things wrong.”

US police brutality

In July 2016 a Facebook live video was censored for showing the aftermath of a black man shot by US police in his car. Philando Castile was asked to provide his license and registration but was shot when attempting to do so, according to Lavish Reynolds, Castile’s girlfriend who posted the video.

The video does not appear to violate Facebook’s community standards. According to these rules, videos depicting violence should only be removed if they are “shared for sadistic pleasure or to celebrate or glorify violence”.

“Facebook has long been a place where people share their experiences and raise awareness about important issues,” the policy states. “Sometimes, those experiences and issues involve violence and graphic images of public interest or concern, such as human rights abuses or acts of terrorism.”

Reynold’s video was to condemn wrongful violence and therefore was appropriate to be shown on the website.

Facebook blamed the removal of the video on a glitch.

Swedish breast cancer awareness video

In October 2016, Facebook removed a Swedish breast cancer awareness campaign that had depictions of cartoon breasts. The breasts were abstract circles in different shades of pinks. The purpose of the video was to raise awareness and to educate, meaning that by Facebook’s standards, it should not have been censored.

The video was reposted and Facebook apologised, claiming once again that the removal was a mistake.

The Autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine explored the censorship of the female nipple, which occurs offline and on in many areas around the world. In October 2017 a Facebook post by Index’s Hannah Machlin on the censoring of female nipples was removed for violating community standards.

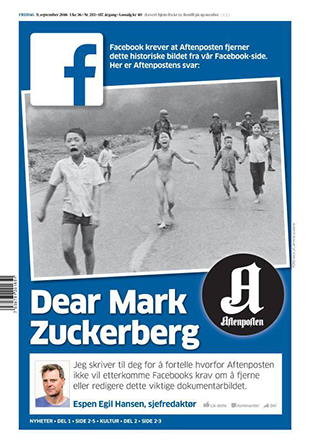

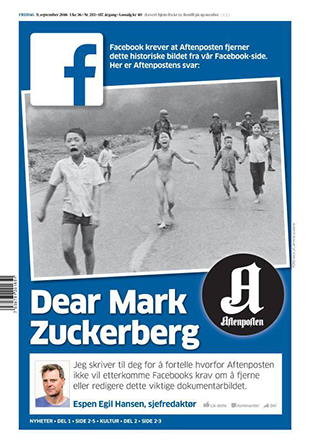

“Napalm girl” Vietnam War photo

A month earlier, in a serious blow to media freedom, Facebook removed an iconic photo from the Vietnam War. The photo is widespread and famous for revealing the atrocities of the war, especially on innocent people like children.

A month earlier, in a serious blow to media freedom, Facebook removed an iconic photo from the Vietnam War. The photo is widespread and famous for revealing the atrocities of the war, especially on innocent people like children.

In a statement made following the removal of the photograph, Index on Censorship said: “Facebook should be a platform for … open debate, including the viewing of images and stories that some people may find offensive, is vital for democracy. Platforms such as Facebook can play an essential role in ensuring this.”

The newspaper whose post was censored posted a front-page open letter to Mark Zuckerberg stating that the CEO was abusing his power. After public outrage and the open letter, Facebook released a statement claiming they are “always looking to improve our policies to make sure they both promote free expression and keep our community safe”.

Facebook’s community standards claim they remove photos of sexual assault against minors but don’t mention historical photos or those which do not contain sexual assault.

The young woman shown in the photo, who now lives in Canada, released her own statement saying: “I’m saddened by those who would focus on the nudity in the historic picture rather than the powerful message it conveys. I fully support the documentary image taken by Nick Ut as a moment of truth that capture the horror of war and its effects on innocent victims.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1509981254255-452e74e2-3762-2″ taxonomies=”1721″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

A month earlier, in a serious blow to media freedom, Facebook

A month earlier, in a serious blow to media freedom, Facebook