24 Sep 2021 | Bosnia, China, News and features, Turkey, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117556″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Almost three decades ago, some three million books and countless artefacts went up in flames when Sarajevo’s National and University Library – inside the Vijecnica (city hall) – was burned to the ground. The destruction of the Vijecnica at the beginning of the war was a symbol for one of the aggressor’s main objectives – silencing the soul of the city and crushing the cultural identity of an entire society.”

So said Dunja Mijatović, the current Council of Europe commissioner for human rights, who was born in Sarajevo when it was part of Yugoslavia.

Just weeks before the anniversary of the burning of the library on 25 August 1992, Mijatović spoke to Index about its symbolism and what its destruction was meant to achieve.

She quoted Heinrich Heine’s play, Almansor: “Where they burn books they will also, in the end, burn people.”

Libraries and archives have been targets for centuries, and the reason is always the same: it’s about taking away knowledge and stifling free thinking.

Libraries are, and have always been, symbols of freedom – the freedom to think and learn and find documents and books to debate and discuss.

Throughout history, when authoritarians take power and seek to control thought and behaviour, they either lock up libraries or destroy the manuscripts and books inside them.

The Serbian forces who burned the Sarajevo library were seeking to obliterate evidence of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s existence as a successful multicultural and multi-ethnic state. The documents they burned told a different history from the one that the army leaders wanted to portray.

Omar Mohammed, who reported as Mosul Eye on the Isis occupation of his city in Iraq, risked his life to blog anonymously about the occupiers’ wish to destroy books as well as to execute people as they sought to repress the population.

Mohammed told Index that it was not just the university library that was destroyed in Mosul, but it was the one that was reported on the most.

Many other libraries, even private collections, were wiped out. “The only possible reason is because knowledge is power,” he said. “Once you prevent people from accessing knowledge then you will have full control over them.”

Like many other scholars who have delved into the history of libraries, Mohammed understands that it is not about the buildings themselves.

“They don’t want people to have this access because they know if people write the history, it will be completely different from the one they wanted it to be,” he said.

Targeting libraries sends out a powerful message to scholars, historians and scientists, he added.

“When they see that such people are able to totally target the libraries, that they are literally able to destroy everything, it’s a manifestation of brutality.”

Today, Richard Ovenden, the most senior librarian at the Bodleian libraries at the University of Oxford, is worried about libraries in Turkey being closed under pressure from the government of president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

According to some sources, at least 188 libraries were closed there between 2002 and 2020.

Ovenden’s book, Burning the Books, looks at the history of the intentional destruction of knowledge. He was recently contacted by a Turkish student, who said: “I’ve just read your book and I want you to know how bad it is in Turkey, because libraries are being destroyed. And all the things that you write about are true in Turkey today.”

Ovenden said: “There is an absolutely authoritarian control over knowledge. Attacks on knowledge are being exercised by the authoritarian leader of Turkey right now. It is the ability for the population to generate their own ideas and to come up with their own thoughts that some governments, some authoritarian powers, some dictators and rulers do not like.”

When dictatorships seek to establish that certain minorities don’t exist, or haven’t lived somewhere, getting rid of the documentary evidence is very convenient.

Archives that establish the existence of Uighurs in China and Muslims in parts of India also look like targets.

Ovenden feels that what is fantastically important about libraries is that they “preserve the past thoughts and ideas of human beings so they’re parts of that evidence base”.

He added: “They’re also disseminating institutions [where] you can borrow the books, you can come and take those ideas away and write other books about them, or pamphlets, or newspaper articles, or whatever it is.”

Governments around the world are failing to protect libraries as a resource, sometimes by withdrawing or drastically reducing funding.

In the UK, almost 800 libraries closed between 2010 and 2019, and a major campaign kicked off in Australia this year to save the national archives.

Michelle Arrow, professor of history at Macquarie University in Sydney, argued in April that if funding cuts were not reversed, irreplaceable audio-visual collections would fall apart. After a public campaign, the national government has delivered some extra funding, but this has not solved all the archives’ problems.

She told Index that with a reduction in staff of almost 25% since 2013, more staff would be needed to deal with the large backlog of requests to view archived material.

She said the archives contained “unique records, and they touch almost every Australian: it is a democratic archive, a collection of ordinary people’s records, rather than famous or renowned Australians”.

While some countries are seeing numerous library closures due to financial or other threats, there are new defenders coming to light. In the coastal city of Santa Cruz in California, there’s a massive investment in upgrades to current libraries, and new ones are opening over the next two years.

Santa Cruz mayor Donna Meyers told Index: “In California, we just tend to believe in public institutions. We believe that public education, public libraries, all of that, lead to a better community, lead to a more informed society.”

Santa Cruz residents passed a special tax – by 78% of the vote – to pay for investment in the libraries which, Meyers says, is a sign of how committed the community is to libraries being around for future generations.

Back in Sarajevo, Mijatović can see the new library that rose from the ashes of the Vijecnica from her terrace.

She said: “One hopes that the soul and the people of Sarajevo will recover and that new generations will hopefully enjoy this magnificent symbol of Sarajevo and, more importantly, live in peace.”

Library destruction in recent history

1914: German troops destroy the library of the Catholic University of Louvain

1939: The Great Talmudic Library in Lublin is destroyed by the Nazis

1966-76: Chairman Mao destroys libraries across China as part of the Cultural Revolution

1976-79: The Khmer Rouge deliberately destroy libraries across Cambodia, including the Phnom Penh national library

2013: Islamic troops set fire to the library in Timbuktu, Mali

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Aug 2021 | Bosnia, News and features, Russia, Serbia, Syria, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras

Thirty years separate the beginnings of conflicts in Bosnia-Herzegovina, where I come from, and Syria, where I work now. Bosnia and Syria are the bookends that encompass the three decades when we lived in a world where our collective conscience, eventually, recognised we had a responsibility to protect the innocent, to bring those responsible for war crimes to justice, and to fight against revisionism and denial. Whereas the Bosnian tragedy of the 1990s marked the (re)birth of these values, the Syrian carnage has all but put an end to them.

Nowhere is this sad fact more apparent than in the expansion of disinformation, revisionism and denial about the crimes perpetrated by the Syrian regime against its own people. As a result, disinformation campaigns have become increasingly vicious, targeting survivors, individuals and organisations working in conflict zones.

Coddled by the ever-expanding parachute of academic freedom and freedom of expression, these unrelenting smear campaigns have ruined, endangered and taken lives. They have eroded trust in institutions, democratic processes and the media and sown division in fragmenting democratic societies. Their destabilising effect on democratic principles has already led to incitement to violence. Left unchecked, it can only get worse.

The disinformation movement has brought together a diverse coalition of leftists, communists, racists, ideologues, anti-Semites and fascists. Amplified by social media, their Nietzschean contempt for facts completes the postmodernist assault on the truth. But more important than the philosophical effect is the fact that disinformation campaigns have been politically weaponised by Russia. Under the flag of freedom of expression, they have become a dangerous tool in information warfare.

I know this, because I am one of their targets.

Beyond the fringe

Earlier this year, the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA), an NGO of which I am one of the directors, flung itself into the eye of the Syria disinformation storm by exposing the nefarious nature of the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media (WGSPM), an outfit comprising mainly UK academics and bloggers.

The CIJA investigation revealed that, far from being fringe conspiracists, these revisionists, employed by some of the UK’s top universities, were collaborating with Russian diplomats in four countries; were willing to co-operate with presumed Russian security agents to advance their agenda and to attack their opponents; were co-ordinating dissemination of disinformation with bloggers, alternative media and Russian state media; appeared to be planning the doxxing of survivors of chemical attacks; and admitted to making up sources and facts when necessary to advance their cause.

The investigation was a step out of my organisation’s usual focus. For almost a decade, CIJA has been working (quietly and covertly) inside Syria to collect evidence necessary to establish the responsibility of high-ranking officials for the plethora of crimes that have become a staple of daily news. More than one million pages of documents produced by the Syrian regime and extremist Islamist groups sit in CIJA’s vaults and inform criminal investigations by European and American law enforcement and UN bodies. These documents tell, in the organisers’ and perpetrators’ own words, a deplorable story of a pre-planned campaign of murder, torture and persecution, a story that started in 2011 when the Syrian regime began its systematic and violent crackdown on protesters.

CIJA’s work is pioneering and painfully necessary as it ensures crucial evidence is secured, analysed and properly stored when there is no political will or ability to engage official public bodies to investigate the crimes. Our evidence has been described by international criminal justice experts to be stronger than that available to Allied powers holding the Nazi leadership to account during the Nuremberg trials. This makes us dangerous and this makes us a target – both in the theatre of war and in the war on the truth.

Before long, we were in the crosshairs of apologists for Syrian president Bashar al-Assad and, soon after that, in those of the Russian-sponsored disinformation networks.

The weaponisation of propaganda

Propaganda has been the key ingredient of every war since the beginning of time. But its unrelenting advance in the midst of the Syrian war is unprecedented. The beginnings of its weaponisation can be traced back to 2015 when the wheels of fortune turned for Syria as Russia got militarily involved in the conflict. Assad was on the way to winning on the ground but the battle to own the narrative of the war was only just beginning. In its advance, Moscow’s disinformation machinery swept up Western academics, former diplomats, Hollywood stars and punk-rock legends. New outfits and personalities mushroomed, bringing a breath of fresh air to the stale and steady group of woo-woo pedlars and conspiracy theorists from the 1990s.

The WGSPM is one such outfit. Founded in 2017, its most prominent members are Piers Robinson, formerly of Sheffield University; Paul McKeigue and Tim Hayward, of the University of Edinburgh; David Miller, of the University of Bristol; and Tara McCormack, of the University of Leicester. Apart from their shared interest in proliferating pro-Assad, pro-Russian Syria propaganda, between them these professors cover 9/11 truthism, Skripal poisoning conspiracies, Covid-19 scepticism, anti-Semitism and Bosnian war crimes denial.

The modus operandi of disinformation in Syria is simple and borrows from how it was done in Bosnia: sow seeds of doubt regarding two or three out of myriad atrocities committed by the Syrian regime in order to put a question mark over the whole opus of criminal acts overseen by Assad over the past decade.

In Bosnia, according to revisionists, Sarajevo massacres were staged or committed by the Bosnian army against its own people, Prijedor torture-camp footage was faked and the number of Srebrenica genocide victims was inflated. In Syria, according to disinformationists, the Syrian regime’s chemical weapon attacks were staged or committed by opposition groups, footage of children and other civilian victims was faked and the number of those who went through the archipelago of torture camps was inflated.

Syria disinformationists make great use of the postmodernist scepticism about evidence and truth in order to advance their theories. They resort to obfuscation, distortion and alternative evidence. The vision is blurred. Questions are important, answers not so much. Context is irrelevant.

There is not much of a change there from the 1990s. The only marked difference is that today’s approach to advancing disinformation focuses much more on tearing down individuals and organisations working in or reporting on the war. In order to make a lie believable, one must discredit those who endeavour to test the truth.

The WGSPM started by disputing that chemical weapons attacks were conducted by the Assad regime, proffering instead pseudoscientific arguments that the attacks either did not happen, or were staged or committed by opposition groups, potentially with the support of Western imperialist governments. They zoned in on two out of more than 300 documented chemical weapons attacks. But two was enough to start sowing the seeds of doubt among wider audiences.

The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) was in the crosshairs as its investigative teams and fact-finding missions returned with findings pointing to the Syrian regime’s responsibility for the attacks over and over again. The OPCW was portrayed to be issuing doctored reports in support of the alleged Western imperialist agenda to overthrow the regime, including by the use of military intervention for which chemical weapons attacks would be a pretext. The disinformationists parroted Damascus and Moscow in whose view all of the alleged chemical attacks were staged on the orders of the West.

The targeting of the White Helmets

A special level of vitriol targeted the White Helmets, a Syrian search and rescue organisation whose cameras record the daily toll of Syrian regime and Russian bombs and chemical weapon attacks on innocent people’s lives as they rush in to pull the victims out of the rubble. They were branded as actors, jihadists and Western intelligence service agents. They were accused with zero evidence of organ-harvesting. The children they pulled out of the rubble were cast as fake or actors. WGSPM members promulgated theories that the White Helmets killed civilians in gas chambers and then laid them out as apparent victims of fake chemical weapons attacks.

The group’s most influential member, Vanessa Beeley, a self-proclaimed journalist residing in Damascus, openly incited and justified the deliberate targeting of the White Helmets, hundreds of whom have died in so-called double and triple-tap airstrikes carried out by the Russian and Syrian air forces. Beeley claimed the White Helmets’ alleged connection to jihadists made them a legitimate target. The jihadists connection itself was a “manufactured truth”. Beeley has spent years producing blogs and twisting the facts to present the White Helmets as aiders and abetters of the extremist armed groups. This falsehood then proliferated in cyberspace, amplified by alternative and Russian state-sponsored media, and eventually parts of these allegations began to stick with wider audiences.

Last year, a study from Harvard University found that the cluster of accounts attacking the White Helmets on Twitter was 38% larger than the cluster of accounts representing their work in a positive light or defending them from orchestrated info warfare.

Soon, Russian state officials started singling out White Helmets’ co-founder James Le Mesurier, branding him as an MI6 agent with connections to terrorist groups. The hounding of this former British soldier was relentless. Le Mesurier was so deeply affected by the relentlessness of the campaign against the organisation, its people and himself that it contributed to the erosion of his psychological wellbeing and, eventually, his death.

The fastest way to erode the credibility of an entity is to discredit its leadership. This is what the disinformation network tried to do with the White Helmets and Le Mesurier. When they started shifting focus to CIJA, the messaging and the mode of its delivery did not change much.

At first, CIJA did not pay attention to the attacks. As with the White Helmets, the coverage of CIJA’s work by the international media was overwhelmingly positive, although with the difference that we were not as prominent in the public eye. But after the New Yorker published a long read in 2016, within days the alternative media and bloggers produced a dozen articles casting doubt over the authenticity or even the existence of the documents in our archive, branding CIJA the latest multi-million-dollar propaganda stunt.

By 2019, things had got more serious. When The New York Times and CNN within days of each other published articles about CIJA’s evidence of Assad’s war crimes, inexplicably it was the Russian embassy in the USA that spoke out first, issuing a statement attacking the media for writing about such an “opaque” organisation. Within 10 days, US online outlet The Grayzone published a lengthy hit piece, calling CIJA “the Commission for Imperialist Justice and al-Qaeda”, claiming we were collaborating directly with Isis and Jabhat al-Nusra affiliates.

It was reproduced in other alternative media outlets and among social media enthusiasts. But, more worryingly, calls from the people who work in the field of international criminal justice and Syria started coming in. These are not the types who would normally believe in conspiracy theories, and the majority of them are apolitical. However, the more the hit piece circulated, the fewer people focused on its source – a Kremlin-connected online outlet that pushes pro-Russian conspiracy theories and genocide denial – and focused instead on what was being said about the people in their field who are so rarely in the media.

Predictably, before long, the allegations raised by the hit piece were being directly or indirectly shared by and referred to on social media by international lawyers and other NGOs in our field. It was a perfect example of the speed and efficiency with which information warfare could penetrate the mainstream.

CIJA and disinformation

In 2020, the WGSPM made it known it was turning its attention to CIJA. The focus, replicating that of the White Helmets attack, was on CIJA founder and director Bill Wiley who was perceived by the conspiracists to be a CIA agent in Canadian disguise working with British money and jihadists to subvert the government of Assad and, in the process, enrich himself. It was one year after Le Mesurier’s death and, by then, the impact the disinformation campaign had on the last months of his life had been well documented.

We would not be sitting ducks. CIJA’s undercover investigation commenced out of fear for the security of its people and operations. Only three out of 150 of us appear in public. Locations of our people and our archives are kept secret. This is not because we are a covert intelligence front but because the threat is real.

Our investigators have been detained, arrested and abused at the hands of both the regime and extremist armed groups. One has been killed. Among the Syrian regime documents in our possession are those that show that Assad’s security intelligence services are looking for our people both inside and outside Syria.

Running investigative teams inside one of the world’s most dangerous countries requires a low profile, independence, access and mobility. The nature of the narrative falsehoods spread by the likes of the WGSPM was such that it threatened each of those requirements.

Being caught in possession of Syrian regime documents in the country would be a death sentence if our people were stopped, either by the regime or by Islamist extremist groups. Linking the organisation to foreign intelligence services or even to jihadist groups makes them easy targets in the theatre of war that is Syria. Allegations of financial or other types of impropriety are a death sentence to organisations that are donor dependent.

This is what makes these disinformation networks dangerous. By proliferating lies and innuendo and obfuscating the reality about organisations and individuals working in the field, they not only threaten to derail the legitimate work we are doing but also directly endanger the lives of the people doing it. This is not what freedom of expression should be about.

The old saying goes, a lie travels halfway around the world before the truth puts its boots on. The influence of disinformation networks today cannot be compared to those of the 1990s. The proliferation of online media outlets, the growing influence of social media, the increasing embrace of alternative facts and multiple versions of truths have all contributed to the dissemination of a skewed picture of what is really happening in Syria.

Even with the constant reporting by the international media of the atrocities the Syrian regime has bestowed on its own people – with thousands of crimes and survivors’ testimonies unrelentingly documented by Syrian and international human rights organisations as well as the UN – Western communities have remained at best on the sidelines in the face of the biggest carnage of this century. The core values of humanity dictate that a collective outcry should have reverberated across the political divide at the sight of gassed children gasping for breath, babies being pulled out of rubble, and emaciated, tortured and decaying bodies strewn around prison courtyards. Yet, by and large, the general population stayed silent. Why? Because the Syrians have been dehumanised on an industrial scale in Western general public opinion.The purpose of disinformation campaigns is to sow the seed of doubt about what is happening, to stoke fear and ultimately to erode trust in democratic processes and human rights values. And that is precisely the effect of the Syria disinformation campaign.

This has been possible only because the revisionists are no longer a fringe group with limited reach. The trajectory of an untruth about the White Helmets just like that about CIJA is very similar: a blog will come out, which will be picked up by a connection in alternative online media, which will then be amplified by Russian state-linked media, which will then be repackaged by Moscow and presented as legitimate facts worthy of discussion in front of the UN Security Council in New York, at the UN in Geneva, and at OPCW State Parties meetings in The Hague. They have even started penetrating parliaments in London, Berlin and Brussels.

With the help of social media, bots and trolls, and in the era of Trumpian contempt for mainstream media, its trajectory can go only upwards.

CIJA’s probe revealed the level of these connections as the Assad apologist from WGSPM Paul McKeigue outlined them in quite some detail in correspondence with our investigators. The campaigns against the White Helmets, the OPCW and CIJA were not isolated attempts to point to inconsistencies in the “mainstream narrative” of the Syrian war. They were an orchestrated attack on what were deemed to be the biggest obstacles to an attempt to whitewash Assad’s crimes.

Although CIJA uncovered the nefarious connections between academics, bloggers and Russian state operatives, the “alternative truth” lives on even when it is proven to be a lie.

Fake news?

For proof, again look at Bosnia. Twenty years ago, Living Marxism magazine went bankrupt after a UK court found that it had defamed ITN and its journalists by claiming the images they recorded in death camps in north-western Bosnia in 1992 were fake. Since then, an international tribunal in The Hague has established beyond reasonable doubt the truth about the macabre crimes that took place in the camps. The journalists’ reports were entered into evidence and withstood rigorous challenges offered by the defence in more than a dozen cases. Yet the claim that this was “the picture that fooled the world” and that the camps were mere refugee centres lives on.

My friend Fikret Alić is the man whose emaciated body behind barbed wire was snapped by cameras on that hot August afternoon in 1992. Thirty years later, he is still tortured by a relentless denial campaign. Weeks ago he was ridiculed on Serbian television by journalists and filmmakers who relied on Living Marxism’s proven lie to back their claims.

It is a never-ending quagmire. As he told Ed Vulliamy, the Observer journalist who reported from the Bosnian camps in 1992: “When those people said it was all a lie and the picture of me was fake, I broke completely. There was nothing they could give me to get me to sleep.”

Living with the nightmare of survival is a lifelong struggle for most. Living with the accusation that what they experienced did not happen condemns them to reliving that torture over and over again.

Mansour Omari, a Syrian journalist who survived a whole year of being bounced around different detention facilities in the Syrian security services’ torture grid, recently wrote that “those who callously deny our torture ever happened are torturers in another guise”. His words are not a poetic metaphor. The psychological and physical suffering for thousands of Fikrets and Mansours subjected to that denial is very much real.

Yet the survivors are effectively told that those whose denial torments them are doing so in the name of free speech and with the aim of challenging injustices. The idea is preposterous. Disinformation encourages discrimination, dehumanisation and prejudice against the victims.

Instead of being denied the platform from which to inflict further pain and incitement, the revisionists are revered and rewarded with peerages and space to spread the poison in the mainstream.

The mainstream media of today is even more reluctant to challenge revisionism than it was in the 1990s. When ITN decided to sue Living Marxism, the debate it ignited in media circles was not about the heinousness of the lie but about whether it was right for a large media outfit to sue a smaller one.

Today’s alternative media go much further than Living Marxism dared to venture. Reports of massacres are challenged by attacking the journalists who bring them. They are claimed to be Western imperialist shills connected to US/UK intelligence services, fabricating reports from Syria with the assistance of Isis or al-Qaeda.

But I have yet to see a mainstream media outlet take steps to defend the honour of its journalists, the integrity of its reporting and the truth in the way ITN did so many years ago. The result? Public trust in the media is in steady decline, with a 20% slump recorded in the UK in the past five years alone.

This is not to undermine the journalists who continue seeking to investigate and understand the actors in the Syrian disinformation network space. But they face more of an uphill struggle to get the space for it from their editors than was the case in the past. The question media management should ask themselves is not if it is unseemly for a large media outlet to defend its journalistic track record by challenging the revisionist lies that make it a target of disinformation. The more important question is whether it is right to let such a falsehood go unchallenged. What impact does it all have in the long run on historic record, on the victims, and on journalistic ethics which include seeking the truth?

Academia, too, has been stunned into inaction as a growing number of university staff abuse their credentials to spread propaganda. Whether gathered in coalitions such as the WGSPM, or working as lone wolves, they have become weaponised agitprop agents of Moscow (in the case of the WGSPM and its affiliates, knowingly and wilfully so, as their members have admitted to be co-ordinating with a variety of Russian diplomats to subvert the work of the OPCW, the White Helmets and others such as CIJA).

Universities are hiding behind academic freedom to explain their lack of action to sanction such wholly unscientific behaviour. The professors and their universities alike claim that these individuals are acting in their private capacity. Yet each one of them links to their university page on the WGSPM website. As plain Paul, Tim, Tara, Piers and David, they would be just another set of fringe conspiracists in the masses. With their full affiliations to prestigious universities listed every time they put their names to a revisionist or disinformationist story, they command credibility.

Fighting the disinformation war

With media and academia becoming major carriers of disinformation, what kind of a history of Syrian conflict is being written?

The perturbing answer of what awaits Syrians and the future discourse about that conflict can be gleaned from what has transpired in Bosnia in the years since. The denial of Bosnian atrocities has not only seeped into the mainstream but is being rewarded at the highest level. In 2019, Peter Handke, a prominent denier of the Srebrenica genocide and supporter of Serb leader Slobodan Milošević, received the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 2020, Claire Fox, who was co-publisher of Living Marxism and continued to deny Bosnia war crimes afterwards, was given a peerage.

What hope is there, then, for the truth about Syria to prevail when Assad apologists are regularly given space in the traditional media, on neo-liberal platforms and within academia? Revisionists such as the WGSPM’s Tara McCormack, who lectures at Leicester University and holds a regular slot on Russia Today and Sputnik, frequently appears on the BBC and LBC, too. The DiEM25 movement, a pan-European organisation whose stated aims are to to “democratise the EU” gives over a whole panel to some of the most vehement Assad apologists, including Aaron Maté who not only denied the survivors their truth but openly mocked them on social media. These are not people who present “diversity” of opinions or ideological or political alignments.

Ultimately, these people, instead of being challenged for their lies and the harm they cause to survivors and others, are being given the space to trickle their pseudoscientific revisionism into the mainstream. It is time to stop giving them a platform. And it is time to challenge them with all lawful means.

It might be unpalatable to read such a proposal in a magazine that stands up against censorship. After all, without freedom of expression and academic freedom we might as well bid goodbye to democracy and human rights. But this crucial value is what revisionists clutch at every time they are called out. In turn, such accusations make most of us uncomfortable to take the necessary steps to tackle a growing problem.

Truth-seeking is supposed to be at the core of universities’ existence, but revisionism and denial do not constitute truth-seeking. Academic freedom should allow for robust debate and challenge the conventional wisdom. But it should not allow for incitement of hatred or slandering of victims, survivors, journalists and others.

Truth matters because disinformation destroys lives, as history has taught us. It torments people: from Fikret Alić to Mansour Omari to James Le Mesurier, to countless others whose names we will never learn.

Disinformation exposes those such as the White Helmets or CIJA working in conflict situations to additional risk. Labelling journalists as security intelligence or jihadi sympathisers puts a target on their backs. The unrelenting advance of disinformation must be stopped before more harm is done.

29 Apr 2020 | News and features

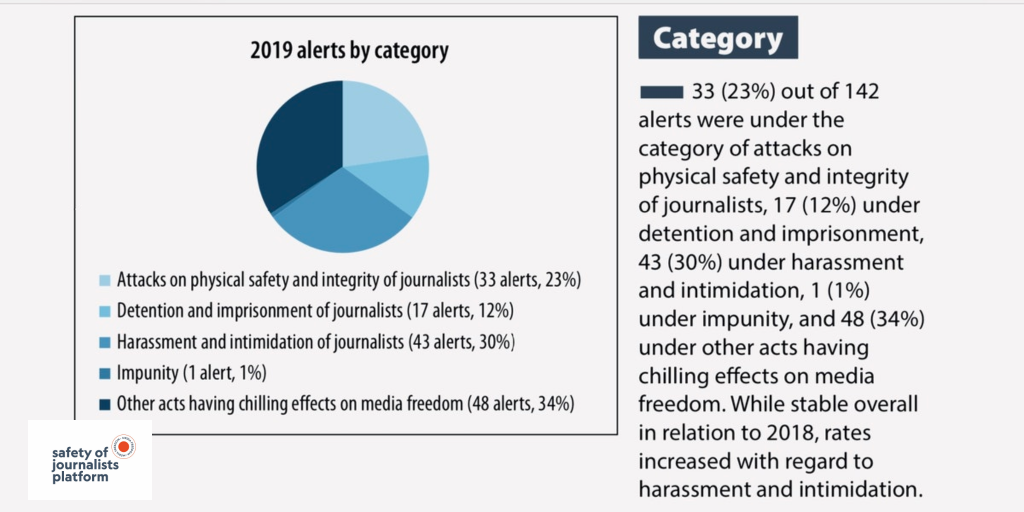

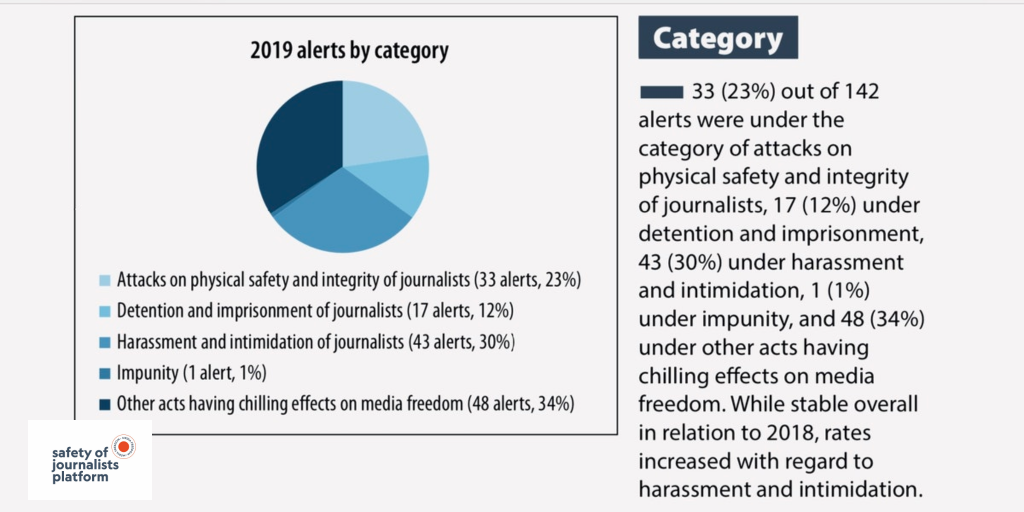

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Attacks on press freedom in Europe are at serious risk of becoming a new normal, 14 international press freedom groups and journalists’ organisations including Index on Censorship warn today as they launch the 2020 annual report of the Council of Europe Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and the Safety of Journalists. The fresh assault on media freedom amid the Covid-19 pandemic has worsened an already gloomy outlook.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

These threats risk a tipping point in the fight to preserve a free media in Europe. They underscore the report’s urgent wake-up call on Council of Europe member states to act quickly and resolutely to end the assault against press freedom, so that journalists and other media actors can report without fear.

Although the overall response rate by member states to the platform rose slightly to 60 % in 2019, Russia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan – three of the biggest media freedom violators – continue to ignore alerts, together with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

2019 was already an intense and often dangerous battleground for press freedom and freedom of expression in Europe. The platform recorded 142 serious threats to media freedom, including 33 physical attacks against journalists, 17 new cases of detention and imprisonment and 43 cases of harassment and intimidation.

The physical attacks tragically included two killings of journalists: Lyra McKee in Northern Ireland and Vadym Komarov in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the platform officially declared the murders of Daphne Caruana Galizia (2017) in Malta and Martin O’Hagan (2001) in Northern Ireland as impunity cases, highlighting authorities’ failure to bring those responsible to justice. Only Slovakia showed concrete progress in the fight against impunity, indicting the alleged mastermind and four others accused of murdering journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová.

At the end of 2019, the platform recorded 105 cases of journalists behind bars in the Council of Europe region, including 91 in Turkey alone. The situation has not improved in 2020. Despite the acute health threat, Turkey excluded journalists from a mass release of inmates in April 2020, and second-biggest jailer Azerbaijan has made new arrests over critical coverage of the country’s coronavirus response.

2019 saw a clear increase in judicial or administrative harassment against journalists, including meritless SLAPP cases, and spurious and politically motivated legal threats. Prominent examples were the false drug charges filed against Russian investigative journalist Ivan Golunov and the continued imprisonment of journalists in Ukraine’s Russia-controlled Crimea. The Covid-19 crisis has strengthened officials’ tools to harass journalists, with dangerous new “fake news” laws in countries such as Hungary and Russia that threaten journalists with jail for contravening the official line.

Other serious issues identified by 2019 alerts included expanded surveillance measures threatening journalists’ ability to protect their sources, including in France, Poland and Switzerland, as well political attempts to “capture” media through ownership and market manipulation, most conspicuously of all in Hungary. These threats, too, are exacerbated by the actions taken by several governments under the health crisis, which further include arbitrary limitations on independent reporting and on journalists’ access to official information about the pandemic.

Jessica Ní Mhainín, Index’s policy research and advocacy officer, says, “There is a growing pattern of intimidation aimed at silencing journalists in Europe. The situation in Eastern Europe – especially in Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria – is particularly concerning. But the killing of Lyra McKee shows that we cannot take the safety of journalists for granted anywhere – not even in countries that are seen to be safe for journalists. This report provides an opportunity for us all to come to grips with the serious situation that is facing European media and to remind ourselves of the vital role that the media play in holding power to account.”

Index and the other platform partners call for urgent scrutiny of action taken by governments to claim extraordinary powers related to freedom of expression and media freedom under emergency legislation that are not strictly necessary and proportionate in response to the pandemic. Uncontrolled and unlimited state of emergency laws are open to abuse and have already had a severe chilling effect on the ability of the media to report and scrutinise the actions of state authorities.

While the platform welcomes an increased focus on press freedom by European institutions, including both the Council of Europe and European Union institutions, the ongoing crisis demands more urgent and stringent responses to protect media freedom and freedom of expression and information, and to support the financial sustainability of independent professional journalism. In the age of emergency rule, protecting the press as the watchdog of democracy cannot wait.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Dec 2017 | Bosnia, Croatia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Journalists who referred to Slobodan Praljak, seen here in 2013, and his co-defendants as war criminals after their conviction have been targeted by parties who think the men are heroes. (Photo: UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia)

Several journalists and news outlets from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina faced death threats and intimidation following their coverage a war crimes trial at the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague, Netherlands.

In the ruling ending the case, six Bosnian Croat leaders were sentenced on several charges for an ethnic cleansing campaign against Muslim Bosniaks during the 1992-95 Bosnian war.

One of the six defendants was Slobodan Praljak, who committed suicide during the delivery of the court’s verdict by potassium cyanide. Just a seconds before taking the poison, the defendant addressed the court: “Slobodan Praljak is not a war criminal! I reject your judgment with contempt!”

What was supposed to be an easy task, writing a news report from a trial, turned out to be a quite delicate situation. The problem stems from how reporters should refer to the convicted men. War criminals or heroes?

For the conservative and right-wing politicians, currently in power in Croatia, the case is clear. The defendants are heroes, regardless of what court has said. Therefore, Praljak and the other five defendants, in line with the nationalistic narrative, should be praised as heroes, while his suicide is seen as a highly moral act. In line with this, the majority of politicians in the Croatian Parliament held a minute’s silence honouring Praljak. Even the Croatian prime minister, Andrej Plenković, said that the UN court’s verdict was a “deep moral injustice” becoming, as the Guardian reported, the first head of an EU government in support of a convicted war criminal. Later, following the national and international critics, Plenković back-pedalled in his narrative, even though keeping “but” in his argumentation.

In this kind of fraught environment the professional media were supposed to objectively inform the public. For those media workers that used “war criminal” to describe Praljak and other five defendants, what followed was a nightmare. A series of death threats, intimidations, insults and bullying, mainly via social media, were issued against all those outlets and journalists who described Praljak as a sentenced war criminal, or were critically analysing Croatia’s involvement in the 1992-95 Bosnian war.

In just a few days, Croatian news website Index.hr and its journalists received tens of serious death threats, including bomb and napalm threats. As reported by the site, the threats included: “I will fuck your treacherous mother. You are a dead man”; and “there will be time when your 18-year-old daughter will be walking alone around the town.”

Nataša Božić Šarić, editor and host of a political talk show Točka na tjedan (Point for the Week), which is aired on regional private broadcaster N1, received death threats and insults on Facebook after the show. Her question to the guests “should the sentenced be stripped of awarded medals?” was considered as provocation by conservative and right-wing viewers.

The most recent report from the Croatian Journalists’ Association (HND) says that the latest in the long line of intimidated journalists is daily Jutarnji list op-ed Jurica Pavičić. He was threaten for his critical column on the Croatian Parliament’s decision to hold a minute’s silence for the defendants.

The Praljak case resulted in similar rhetoric and threats in neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the war crimes were committed. Sanel Kajan, a journalist and correspondent for the regional private broadcaster Al Jazeera Balkans (AJB), received threats from his fellow citizens, Bosnian Croats, for using his voice for the announcement of a special show on the ICTY trial on AJB and for sharing colleagues’ pieces on Facebook.

“I received a ton of threatening messages via Facebook,” Kajan told Index on Censorship. “At the beginning I was just deleting them, but once I realized the gravity, as threats were multiplying every minute, I decided to report the case to the police,” he said. Among the numerous Facebook messages there were death threats like “You won’t be alive for a long time. I promise you this”; and a religious-based ones like “Shame on you, you unbaptised Satan”.

This is not the first time these kind of threats have been “provoked” by objective reporting while nationalistic reports have been praised as true, patriotic journalism. Similar incidents have happened in all post-conflict Balkan states. In recent years, Mapping Media Freedom has documented similar cases in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo and the Republic of Macedonia. In all those cases media workers were threatened, intimidated and bullied for questioning nationalistic dogmas.

Zdenko Duka, a well-respected Croatian journalist and former president of HND pointed out that there is plurality in the society which is backed by professional and critical media. “But unfortunately the ruling elite is pushing towards nationalistic rhetoric as a compensation for their incompetence and cowardness,” Duka said. Elaborating on the power dynamics he said that “the Catholic Church and the war veterans” are influencing Croatian politics through the ruling conservative Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). “Veterans are a privileged group with 2-3 times higher average pensions than the rest of the citizens,” Duka explained.

Croatia’s public and politicians have applied doubles standards to the ICTY verdicts: The court is praised when others are found guilty, but denounced as corrupt when it convicts “heroes”. For years this line of argument has been validated in the public discourse. Srdjan Puhalo, a political analyst from Bosnia and Herzegovina, calls this phenomenon the “moral incompleteness” of the Balkan societies.

“Nowadays is hard to critically analyse the 90s wars. If you write critically you will be called a traitor, and everybody knows what one should do with traitors. Bottom line is that it is you against the system which is backing up the 90s ‘heroes’,” Puhalo said. The only exit out of this vicious circle, according to him, is time. “At the end, only the verdicts will stay throughout history and everything else will be forgotten,” Puhalo concludes.

It is even more important that these kinds of threats against press freedom are not minimised and left unpunished.

“If there will be no concrete action/investigation/outcome out of this then the message will be loud and clear: You are free to intimidate them, and journalists should shut up,” Kajan said.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified more than 3,700 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”10″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”2″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1513934685366-7918602e-7d9f-0″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]