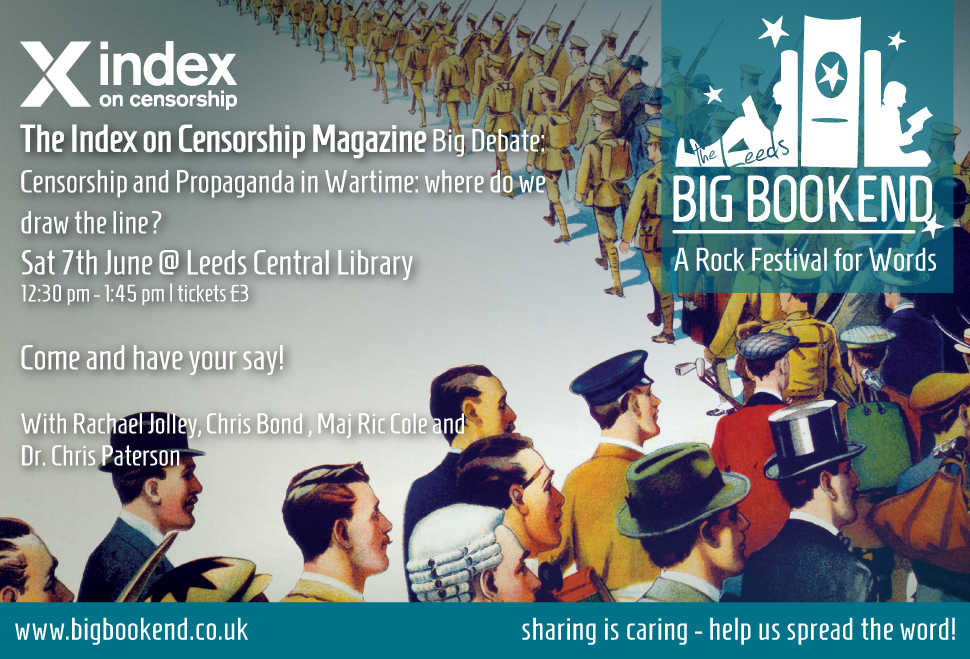

7 June: Propaganda in wartime – where do we draw the line?

Join Index on Censorship Magazine at Leeds Big Bookend Festival to debate whether it is acceptable for governments and others to withhold information from the public during a conflict or war.

Is it always unreasonable not to tell the public the whole truth? Is propaganda sometimes necessary? Maybe the USA wouldn’t have entered WWII without it, so can it be justified? Does propaganda or censorship matter? Why and when should we care?

With Major Ric Cole (Former Royal Marines Commando & Infantry Officer), Dr Chris Paterson (author ‘War Reporters Under Threat: The United States and Media Freedom’), Chris Bond (Yorkshire Post & Legacies of War) and Rachael Jolley (Editor, Index on Censorship Magazine).

When: Saturday 7th June, 12:30 – 13:45pm

Where: Leeds Central Library, LS1 3AB

Tickets: Book your tickets here.

China: Censors work overtime for Tiananmen anniversary

“Keep quiet and carry on” is the slogan that can best describe China’s take on the approaching 25th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

This is the yearly Tiananmen anniversary crackdown, and people within China know what to expect; slower internet, blocked search terms, more military personnel in public and the arrest of high profile individuals. But this year’s crackdown appears particularly thorough, either a reaction to dissent being higher than usual or a perception that it is in light of the milestone anniversary.

The Chinese government has already jailed scores of lawyers, activists and intellectuals, sending a chilling message to any other would-be agitators. Of the most widely reported was the arrest of Pu Zhiqiang, a prominent human rights lawyer who helped organise the 1989 protests. His detention came three days after he joined a private panel discussion on the massacre. Around 15 people were at the event, five of whom have since been detained. Then there was the airing of confessions on state media by journalist Gao Yu and citizen journalist Xiang Nanfu this May, which echoes Maoist propaganda tactics.

As we get closer to 4 June actions against freedom of expression will grow. Yvonne Shen, who is Asia News Digest Editor at Freedom House, an NGO committed to tracking violations to free expression, says the Chinese government “step up their censorship efforts in the days surrounding that date”. Within a week the organisation anticipate spikes in suspicious activity online. They are keeping a close eye on social platform WeChat in particular, given its current popularity.

“There was a leaked document dated 31 May, 2011, from the Beijing Municipal Government, that suggested the authorities had launched a ‘wartime coordination mechanism’ that required all units to report suspicious information during the “sensitive period,” Shen tells Index of the government’s usual tactic.

China forbids open discussion of the Tiananmen Square crackdown, in which soldiers fired on crowds of unarmed pro-democracy protesters, killing hundreds if not thousands (no official death toll has ever been released). On top of arrests, an army of censors work overtime to ensure mentions of the event are quickly removed. Sites are blocked and words that allude to or directly reference it vanish.

The private realms of emails and direct messages are also monitored, as Louisa Lim, author of upcoming book The People’s Republic of Amnesia, Tiananmen Revisited, describes: “I wrote my book on a brand-new laptop that had never been online. Every night I locked it in a safe in my apartment. I never mentioned the book on the phone or in e-mail, at home or in the office — both located in the same Beijing diplomatic compound, which I assumed was bugged.”

Chinese journalists are trained “not to ever touch Tiananmen with a 10 foot pole,” Beijing-based journalist Eric Fish tells Index. He too perceives a recent shift: “The atmosphere for Chinese journalists has tightened quite a bit in general since Xi Jinping came to power. It feels like they’ve clamped down a lot more than normal in the lead-up to this anniversary.”

As Fish says, the detentions form part of a broader crackdown on free speech. When Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, there were hopes he would relax censorship. These hopes were quickly dashed. Index recently reported on a ban of seemingly innocent US TV shows, which shows just how pervasive the attack has been.

Even foreign journalists, who are usually granted more leeway, have experienced “a big uptick in pressure over the past two years,” says Fish, a reference to several prominent cases of journalist visas being revoked.

This is a fact Steven Levine has had to accept. “I anticipate being refused a Chinese visa the next time I apply to visit China as this is one way in which the Chinese authorities punish foreigners who criticise their human rights practices,” explains the retired professor of Chinese history and politics, who coordinates the Tiananmen Initiative Project — an individual effort aimed at focussing attention on the Tiananmen Movement and government crackdown.

Levine’s project has already been banned from the Chinese online world; within days of launching last November, the site had been blocked. Levine will not be deterred and continues to correspond with Chinese individuals inside the country, as well as with exiled Chinese who were either leaders or active in the 1989 movement. For him, being refused a visa is a price worth paying. It’s a different story for those inside of China, who take a much bigger gamble.

That said many have come up with creative ways to circumvent censorship. For example, prominent writer Murong Xuecun avoided the censors by using the politically neutral word “tractors” instead of the highly provocative “tanks”. And while “4th June” is blocked, the new code of “May 35th” has filled its place — a count of that month’s 31 days plus four in June.

It’s a game of cat and mouse. Ultimately, the cat is winning, but the mice aren’t going down without a fight.

This article was posted on May 23, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Padraig Reidy: Why does everyone want to be censored?

Nick Griffin, leader of the British National Party, arrives at a protest in June 2013 in Westminster. (Photo: Paul Smyth / Demotix)

BBC Radio Five Live’s Breakfast yesterday dutifully carried out its public service remit by interviewing Nick Griffin, the world’s most tedious Nazi demagogue, ahead of the European elections. Griffin’s British National Party does have some seats in the European Parliament, so is entitled to some airtime.

It was a dull interview. They always are. The BBC interviewers–in this case, Nicky Campbell–want to pick away at the BNP facade, but always somehow miss out on the really strange stuff. Long ago, I vowed that I would never write about Griffin without pointing out that he had written a pamphlet called “Who Are The Mindbenders?”, which is a catalogue of Jewish and Jewish people who work in the media. Griffin believes that these evil Jews (sorry, “Zionists”) are involved in an enormous plot to keep him–the saviour of the white race–out of the press and off the airwaves.

The conspiracist aspect of BNP policies is often overlooked, with the straightforward racism critiqued more heavily. So it was here. Campbell asked Griffin if he had a problem with black and mixed-race players representing England in the upcoming World Cup. Griffin, barely missing a beat, started complaining about BBC liberals smearing him and worse, denying him airtime.

“The BBC owes me 12 Question Times,” he declared, bemoaning his lack of invitations to appear on the BBC’s Thursday night festival of shouting from and at the telly.

It might have been interesting to delve into why Griffin felt he was being kept off Question Time, to see how long he would be able to maintain a line before going full Doctor Strangelove. As it was, we got only the superficial whine. The whine of the martyr-bully.

It is the background sound of our time. There is absolutely no one engaged in modern public life at any level at all who has not complained that they’ve been silenced, denied a platform, bullied into submission by a cruel cabal of agents of reaction or “the liberal agenda”, take your pick.

That is not to say people are not censored, even in the lovely modern 21st Century. It happens, quite a bit. People get locked up for saying stupid things on the internet that affront public sentiment. For years the libel laws restrained reporters, reviewers and the man on the Clapham Omnibus from saying what they really knew, or thought, or thought they knew. And no reader of this site needs to be told what happens in the less than democratic countries all over the world.

But there is actual censorship, and there is the claim to being censored, which are often two separate things. The BNP’s Griffin, UKIP’s Nigel Farage, and every Blimp all the way to Westminster delights in telling us, at length, the things that nobody, least of all them, is allowed to talk about anymore.

Meanwhile, on the left and the pseudo-left, there is an obsession with “platforms”; who has one, who deserves one, who is denied one. Editors and writers who do their best to represent as many diverse views as possible are denounced routinely for the articles they haven’t published rather than the ones they have. Every oversight is evidence of a conspiracy rather than a cock-up. The right people are always being excluded by the wrong people. If only, if only everyone shut up and let me speak, we think, then I could sort everything out.

It’s ironic that many of those who argue most vehemently that they are being censored are the exact ones who demand everyone else shut up. Intersectional feminists who insist they are being excluded from debate demand that radical feminists be “no platformed”. Ukipers who claim they’re not allowed talk about immigration want the police to arrest their opponents in anti-racist movements. All of them, simultaneously, noisily, will end up invoking Niermoller’s “First they came for…” (with the possible exception of the BNP, who, stopping short of displaying sympathy with Communists or Jews, instead content themselves with calling their opponents “the real fascists”, as I once heard Griffin do at Oxford Union).

Why is this? Why does everyone want to be censored?

It’s possible that the simple reason is that we are constantly improving as a society. Triumphalism and privilege are pretty much taboo for many. On the face of it, most of the people reading this, and certainly the person writing it, are probably the luckiest sons of bitches to ever have walked the earth. But a combination of our still-relevant horror at the great wars of the last century, plus a greater ability to learn about the ideas and experiences of others, make most of us wary of revelling in our role as the victor. Instead, we prefer to be the underdog, because underdogs are more virtuous–victims rather than perpetrators. Martyrs, even.

The Nazis and Communists of the 20th century also believed they were more sinned against than sinning, but the difference was that they were certain they would show the world who was really boss. Now, no one outside the most extreme movements – Al Qaeda; or North Korean Juche – really wants to state that aim openly. We want to remain oppressed. Censorship is considered almost universally as a bad thing, so people on whom it is inflicted are good.

The background whine of censorship, emanating even from the powerful may just be the tiny price we pay for a world that is generally better and kinder.

I think we can live with that.

This article was posted on May 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org