14 May 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Media Freedom, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100332″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]All that is solid in the Turkish media melted into air over the past year, and much of the entertainment content has migrated from traditional platforms to streaming services like YouTube and Netflix.

Turkey’s watchdogs took notice. In March parliament passed a law that expands the powers of Turkey’s Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK), including blocking internet broadcasts. With the new law the state hopes to have some degree of control over online content that it considers dangerous.

This spring, many bulwarks of Turkish media have shape-shifted. In April, Turkey’s biggest media conglomerate, Doğan, changed hands. Foreign media titles with Turkish editions, including the Wall Street Journal, Newsweek and Al Jazeera, have already pulled out of the Turkish market. Newspaper circulations saw sharp decline.

Meanwhile online streaming services have thrived. Spotify entered Turkey in 2013 and pushed its premium service with a Vodafone deal two years later. On Twitter, BBC’s Turkish service has just short of three million followers. Netflix introduced its Turkish service in 2016. Last year it too signed a deal with Vodafone, and Netflix Turkey pushed its products aggressively, with posters of House of Cards plastered in Istanbul’s subway stations.

Statista, an online statistics website, predicts there will be approximately 397.4 thousand active streaming subscribers to Netflix in Turkey in 2019.

Turkish-owned streaming services also came to the fore. In 2012 Doğuş Media Group launched its video on demand service, puhutv, and there was excitement last year when the channel showed its first series, Fi, based on a best-selling trilogy by Turkish author Azra Kohen. The series quickly became a sensation, largely thanks to scenes featuring nudity and racy sexual encounters.

Puhutv is a free, ad-supported service and watching Fi on Puhutv meant seeing many ads of condoms, dark chocolates and other products linked with pleasure. In just three days, the pilot episode of Fi was viewed more than four and a half million times.

For content producers the Turkish love for the internet means new opportunities for profit. In February a report by Interpress found that the number of internet users increased by 13 percent to 51 million from the past year. Turkey is one of the largest markets for social media networks and it ranks among the top five countries with largest Facebook country populations.

The RTÜK watchdog, which now has great control over streaming services, normally chases television broadcasters. It famously went after popular TV dating shows last year, and producers faced heavy fines accused of violating ‘public morals’. Marriage with Zuhal Topal, Esra Erol and other shows were pulled off the air. A famous dating show duo, Seda Sayan and Uğur Arslan, considered releasing their show Come Here if You’ll Get Married on the internet.

Those dating shows outraged not only conservatives but many other swaths of Turkish society. Feminists considered them an affront to women’s struggle and they signed a petition to ban dating shows en masse. RTUK announced there were around 120 thousand complaints from viewers about the shows.

With the new bill, producers of shows streamed online will need to obtain licenses. “The broadcasts will be supervised the same way RTÜK supervises landline, satellite and cable broadcasts,” reads the new law which gives RTÜK the power to ban shows that don’t get the approval of Turkish Intelligence Agency and the General Directorate of Security.

Family Ties, a recent episode of the US series Designated Survivor angered many viewers when it was broadcast last November. One of the characters in the episode was a thinly veiled representation of Fethullah Gülen, an imam who leads a global Islamist network named Hizmet (‘The Service’).

The Turkish state accuses Hizmet, its US-based leaders and followers in the Turkish Army of masterminding 2016’s failed coup attempt, during which 250 people were killed. Turkey has requested Gülen’s extradition.

But in Family Ties, the Gülen-like character was described as an “activist”, and this led to protests on Twitter in Turkey. Some Turks wanted the show banned. In Turkey Designated Survivor is streamed by Netflix.

In September Netflix will release The Protector, its first Turkish television series by up and coming film director Can Evrenol. “The series follows the epic adventure of Hakan, a young shopkeeper whose modern world gets turned upside down when he learns he’s connected to a secret, ancient order, tasked with protecting Istanbul,” according to a Netflix press release.

“Streaming services give freedom and enthusiasm to directors who are normally reluctant to work for television,” Selin Gürel, a film critic for Milliyet Sanat magazine said.

“Content regulations are unwelcome, but I don’t think anyone would give up telling stories because of them. Directors like Can Evrenol are capable of finding some other way for protecting their style and vision.”

In Gürel’s view, the new regulations will not lead to dramatic changes for Turkish films.

“It is annoying that RTÜK now spreads its control to interactive platforms like Netflix,” said Kerem Akça, a film critic for Posta newspaper. “RTÜK should keep its hands away from paid platforms.”

Akça has high expectations from Evrenol’s new film, but he fears the effects of new regulations on The Protector and future Turkish shows for Netflix can be harmful.

“The real problem is whether RTÜK’s control on content shape-shifts into self-censorship,” Akça said. “Before it does, someone needs to take the necessary steps to avoid content censorship on Netflix.”

But Turkish artists have long found ways of avoiding the censors, and new regulations can even lead to more original thinking.

“This is a new zone for RTÜK,” Gürel, the critic, said. “I am sure that vagueness will be useful for creators, at least for a while.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Press freedom violations in Turkey reported to Mapping Media Freedom since 24 May 2014

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526292811243-b24bb16c-ba6d-1″ taxonomies=”7355″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Award-winning writer, human rights activist and columnist Aslı Erdoğan

“When I understood that I was to be detained by a directive given from the top, my fear vanished,” novelist and journalist Aslı Erdoğan, who has been detained since 16 August, told the daily Cumhuriyet through her lawyer. “At that very moment, I realised that I had committed no crime.”

While her state of mind may have improved, her physical well-being is in jeopardy. A diabetic, she also suffers from asthama and chronic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“I have not been given my medication in the past five days,” Erdoğan, who is being held in solitary confinement, added on 24 August. “I have a special diet but I can only eat yogurt here. I have not been outside of my cell. They are trying to leave permanent damage on my body. If I did not resist, I could not put up with these conditions.”

An internationally known novelist, columnist and member of the advisory board of the now shuttered pro-Kurdish Özgür Gündem daily Erdoğan was accused membership of a terrorist organisation, as well as spreading terrorist propaganda and incitement to violence.

According to the Platform for Independent Journalism, Erdoğan is one of at least 100 journalists held in Turkish prisons. This number – which will rise further – makes Turkey the top jailer of journalists in the world.

Each day brings new drama. Erdoğan’s case is just one of the many recent examples of the suffering inflicted on Turkey. It is clear that the botched coup on 15 July did not lead to a new dawn, despite the rhetoric on “democracy’s victory”.

Turkey faces the same question it did before the 15 July: What will become of our beloved country? Like the phrase “feast of democracy” – which has been adopted by the pro-AKP media mouthpieces – it has been repeated so often that it habecome empty rhetoric.

Such false cries only serve the ruling AKP’s interests. Even abroad there are increased calls that we should support the government despite the directionless politics in Turkey and the state of emergency.

In a recent article for Project Syndicate entitled Taking Turkey Seriously, former Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt wrote: “The West’s attitude toward Turkey matters. Western diplomats should escalate engagement with Turkey to ensure an outcome that reflects democratic values and is favorable to Western and Turkish interests alike.”

Lale Kemal took Turkey seriously. As one of the country’s top expert journalists on military-civilian relations, Kemal stood up for the truth, barely making a living as no mogul-owned media outlet would publish her honest journalism. She headed the Ankara bureau of independent daily Taraf, now shut down because of the emergency decree. She now sits in jail for the absurd accusation that she “aided and abetted” the Gülen movement, an Islamic religious and social movement led by US-based Turkish preacher Fethullah Gülen. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan refers to the movement as the Fethullahist Terrorist Organisation (FETO) and blames it for orchestrating the failed coup.

But actually, Kemal’s only “crime” was to write for the “wrong” newspapers, Taraf and Today’s Zaman.

Şahin Alpay also took Turkey seriously. As a scholar and political analyst he was a shining light in many democratic projects and one of the leading liberal voices in Turkey.

Three weeks ago, he was detained indefinitely following a police raid at his home. His crime? Aiding and abetting terror, instigating the coup and writing for the Zaman and Today’s Zaman. This last point is now reason enough to deny such a prominent intellectual his freedom.

Access to the digital archives of “dangerous” newspapers – Zaman, Taraf, Nokta etc – is now blocked. This is a systematic deleting of their entire institutional memory. All those news stories, op-ed articles and news analysis pieces are now completely gone.

Basın-İş, a Turkish journalists’ union, stated that 2,308 journalists have lost their jobs since 15 July, and most will probably never to be employed again. Unemployment was their reward for taking Turkey seriously.

Erdoğan, Kemal and Alpay, like many journalists, academics and artists who care for their country, are scapegoats for the erratic policies of those in power.

Even businessmen have fallen victim to the massive witch hunt against “FETO”. Vast amounts of assets belonging to those accused of being Gülen sympathisers have been seized and expropriated by the state. Not long ago these businessmen were hailed as “Anatolian Tigers”, who opened the Turkish market to globalisation.

The seizures will probably draw complaints at the European Court level. They are sadly reminiscent of the expropriations at the end of the Ottoman Empire, which had targeted mainly Christian-owned assets.

What all of these cases have in common isn’t the acrimony that pollute daily politics in Turkey. It is the total sense of loss for the rule of law, made worse by post-coup developments.

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

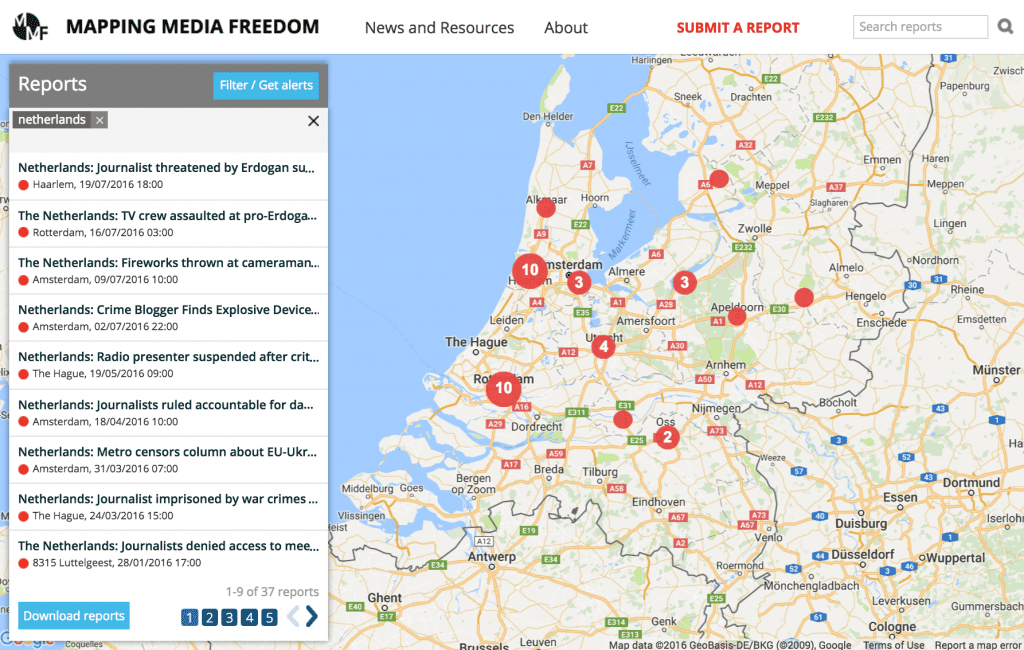

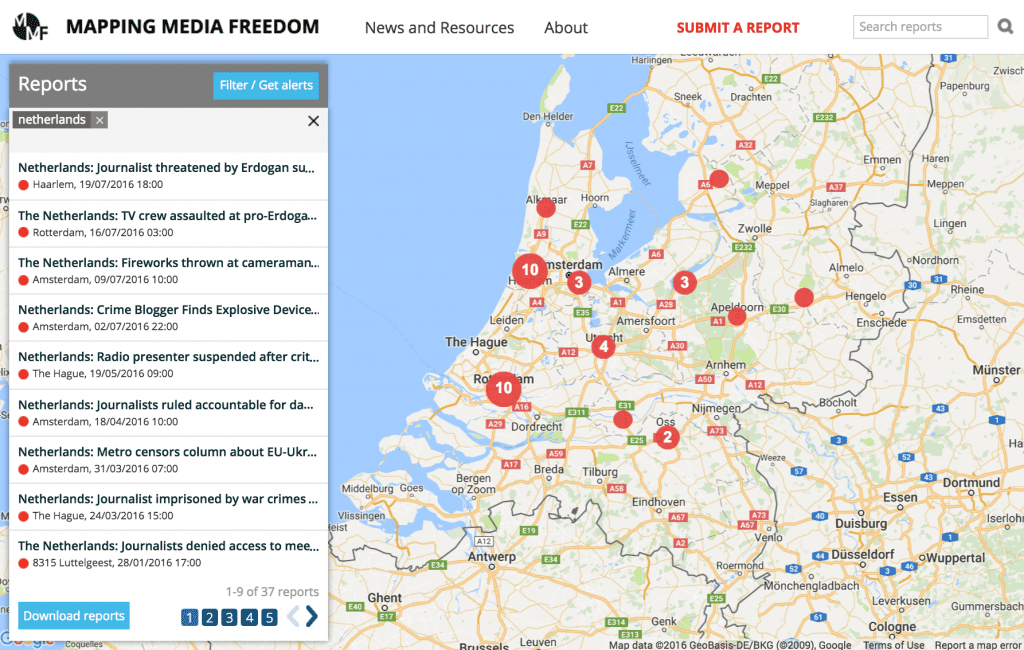

3 Aug 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Netherlands, News and features, Turkey

Following last month’s failed coup, journalists in Turkey are facing the largest clampdown in its modern history. Journalists covering the events from abroad have not escaped unscathed, including a number in the Netherlands who have faced threats and attacks.

Unusually, the journalists of the Rotterdam-based Turkish newspaper Zaman Today welcomed the increased police presence. Long before the military coup that failed to remove Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan from power, the government had been targeting journalists. But today a Dutch police officer drops by frequently to check if Zaman’s journalists are alright. It makes journalist Huseyin Atasever, who has been working for the Dutch Zaman since 2014, feel safe. Or at least safer than he has felt in a while.

On the morning of Tuesday 19 July Atasever was on his way to Amsterdam when he received a phone call. A Turkish-Dutch individual had been abused by Erdogan supporters at a mosque in the city of Haarlem. Atasever decided to go there immediately.

“I found a man sitting in a corner on the floor talking to the police,” he told Index on Censorship. “He was injured and his clothes were torn.”

After Atesaver had interviewed the victim, who had been targeted for being critical of Erdogan, he approached a group of Erdogan supporters nearby to hear their side of the story.

“When these men realised that I work for Zaman Today, things got grim,” Atasever said. “A few of them surrounded me and started shouting death threats at me. They told me ‘we will kill you, you are dead’.”

“Thanks to immediate police intervention I managed to get away unhurt,” he added.

More than ever before, Turks all over the world have seen their diaspora communities divided between supporters and critics of Erdogan.

At around half a million people, the Netherlands has one of the largest Turkish communities in Europe. In the days after the coup, thousands of Dutch Turks took to the streets in several cities to show their support for the Turkish president. Turks critical of the Erdogan government had told media that they’re afraid to express their opinions due to rising tensions.

People suspected of being supporters of the opposition Gulen movement, led by Erdogan’s US-based opponent and preacher Fethullah Gulen, which has been accused of being behind the coup attempt, have been threatened and physically assaulted in the streets. The mayor of Rotterdam, a city with a large Turkish community, urged Dutch-Turks to remain calm and ordered increased police protection of Gulen-aligned Turkish institutions.

The men who had threatened Atasever were arrested, but released shortly afterwards. Atasever said he has pressed charges against them. He still receives threats on social media every day: he has been called a traitor, a terrorist and a coup supporter on Twitter. His photo and contact details have been shared on several social network sites accompanied by messages like “he should be hanged” and “let’s go find him”.

On 1 August Zaman Today’s Dutch website was hit by a DDoS attack and knocked offline for about an hour. An Erdogan supporter reportedly had announced an attack on the website earlier via Facebook, and Zaman Today announced it will be pressing charges.

It hasn’t just been journalists of Turkish descent who have been attacked. During a pro-Erdogan demonstration at the Turkish Consulate in Rotterdam, a TV crew for the Dutch national broadcaster NOS was verbally harassed by a group of youth. NOS reporter Robert Bas told the network that his cameraman had been assaulted and their car was also damaged. “There’s a very strong anti-western media atmosphere here,” Bas said in a live TV interview at the scene.

The Dutch Union for Journalists (NVJ) is worried about growing intimidation of journalists in the Netherlands, NVJ chairman Rene Roodheuvel said in Dutch daily Trouw. “The political tensions at the moment in Turkey and the attitude towards journalists there may in no circumstance be imported into the Netherlands,” he said. “We are second in the world when it comes to press freedom. Media freedom is a great good in the Dutch democracy and it must always be respected.”

“AKP supporters believe that media, especially in the west, are part of an international conspiracy to overthrow Erdogan,” Atasever said. Being a journalist for Zaman Today, he is not new to receiving threats. Many Turks feel the Western media is “the enemy”, he explained. “But we are even worse because we are of Turkish descent. They see us as traitors of our country.”

The government took control of the Turkish edition of Zaman in March 2016. Zaman was a widely distributed opposition newspaper, and very critical of the Erdogan government. The paper had ties with Gulen, who has denied any involvement in the coup attempt, but the Turkish government accuses him a running a parallel government. Zaman and its English-language edition, Today’s Zaman, have since been turned into a pro-government mouthpiece.

Most of Zaman’s foreign editions, however, have so far avoided government control. Zaman has editions in different languages around the world. The Dutch edition, Zaman Vandaag, with a circulation of 5,000, has managed to keep its editorial independence.

While independent journalists in Turkey are being arrested one by one, journalists of Turkish descent in the Netherlands are starting to worry too. “I know for a fact that our names have been given to the Turkish government by Dutch AKP supporters, labelling us as traitors and enemies of the state,” said Atasever, who has no plans to travel to Turkey.

“If our names are on a wanted list, which I expect they are, we will be arrested as soon as we set foot in Turkey.”

18 Dec 2014 | News and features, Turkey

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Photo: Philip Janek / Demotix)

What’s wrong with Turkey? Or, more to the point what is wrong with Turkey’s president that makes him so determined to fight, like a two a.m. drunk vowing to take on all comers?

In the past week alone, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his allies have launched attacks on his former ally Fethullah Gülen and his followers, novelists Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak, and even supporters of Istanbul soccer club Besiktas. It would be foolish to attempt to rank these attacks in terms of importance or urgency, but the attack on the Gülenites is the most interesting.

The Gülen movement was almost unknown to anyone outside Turkey and the Turkish diaspora until 2008, when Fethullah Gülen topped an online poll run jointly by Prospect and Foreign Policy magazines. The poll was almost certainly hijacked by members of the movement, which its leader modestly claims doesn’t really exist (“[S]ome people may regard my views well and show respect to me, and I hope they have not deceived themselves in doing so,” Gülen conceded in an interview with Foreign Policy. “Some people think that I am a leader of a movement. Some think that there is a central organization responsible for all the institutions they wrongly think affiliated with me. They ignore the zeal of many to serve humanity and to gain God’s good pleasure in doing so.”)

The movement, known to some as “Hizmet”, is seen as bearing great power in Turkey. In a country well used to conspiracy theories about secret organisations — such as the perceived ultra-nationalist, ultra-secular Ergenekon — it is unsurprising that the Gülenists attract suspicion. Their cultishness does little to allay that sentiment.

Among the many weapons at the disposal of the movement are its newspapers, the Turkish Zaman and English-language Today’s Zaman. It was journalists from Zaman, among others perceived as Gülenites, who were arrested over the weekend, as reported by Index.

The move by Erdoğan against Gülenists is widely seen as part of Erdoğan’s defence against allegations of corruption within his party — allegations he believes are led by Gülenists within the police and other agencies.

With their journalists arrested, the Gülenists now find themselves facing the kind of censorship they themselves espoused not so long ago.

In 2011, journalist Ahmet Sik was working on a book called Army of the Imam, which was sought to expose the Gülenists’ connections with the police. The manuscript was seized by authorities. When Andrew Finkel, then a columnist with Today’s Zaman (and occasional Index contributor), submitted an article suggesting that the Gülen movement should not support such censorship, he was sacked by the paper. (The column subsequently appeared in rival English-language newspaper Hurriyet Daily News)

It’s tempting amid all this to wish for a plague on all their houses. But as one Turkey watcher pointed out to me, it’s inevitable that some innocents will get caught in the crossfire between the former allies in Erdoğan’s Islamist AK party and the Gülen movement.

Meanwhile, in keeping with the paranoid style of Turkish politics, pro-Erdoğan newspaper Takvim identified an external enemy in the shape of an “international literature lobby”.

The agents of that lobby, which is clearly anti-Turkish rather than pro-free speech, were identified as Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak. It is, in its own way, true that Shafak and Pamuk are part of the international literature lobby: London-based Shafak can often be seen at English PEN events, and Pamuk has long been identified as a literary and free speech hero around the world. But it is an enormous stretch to imagine that the novelists of the world are gathering in smoke-filled rooms plotting the overthrow of the Turkish state, rather than just hoping that Turkish people should be allowed write and read books in peace. Takvim went as far as to imagine that the authors were paid agents of the “literature lobby”, which is to make the terrible mistake of imagining there’s money in free speech. No matter: paranoia excels at inventing its own truths.

Amidst all this, less glamorous than Pamuk and Shafak, less powerful than Gülen and Erdoğan, fans of Besiktas football club too face persecution. The “Çarşı” group are claimed to have attempted a coup against the government after playing a prominent role in the Gezi park protests. Supporters of the tough working class Istanbul club, known as the Black Eagles, have a reputation for anti-authoritarianism and political activism. According to Euronews’ Bora Bayraktar: “While the court’s verdict is uncertain, what is known is that the Çarşı fans – often proud to be ahead of their rivals – have become the first football supporters’ group to be accused of an attempted coup.”

A source in Istanbul tells Index that when asked how he answered to the charge of fomenting a coup, one accused supporter replied: “If we’re that strong we would make Beşiktaş the champions!”, a prospect as unlikely for the underdog club as a dull but functioning liberal democracy seems for Turkey.

This article was posted on 18 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org