27 Apr 2018 | Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

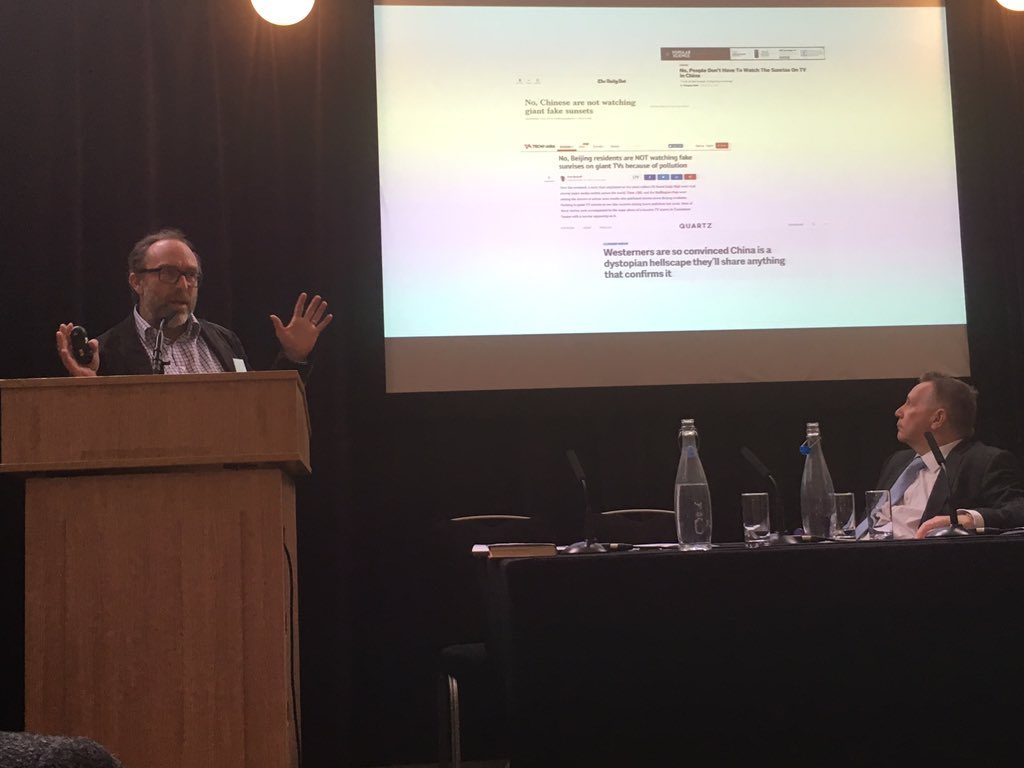

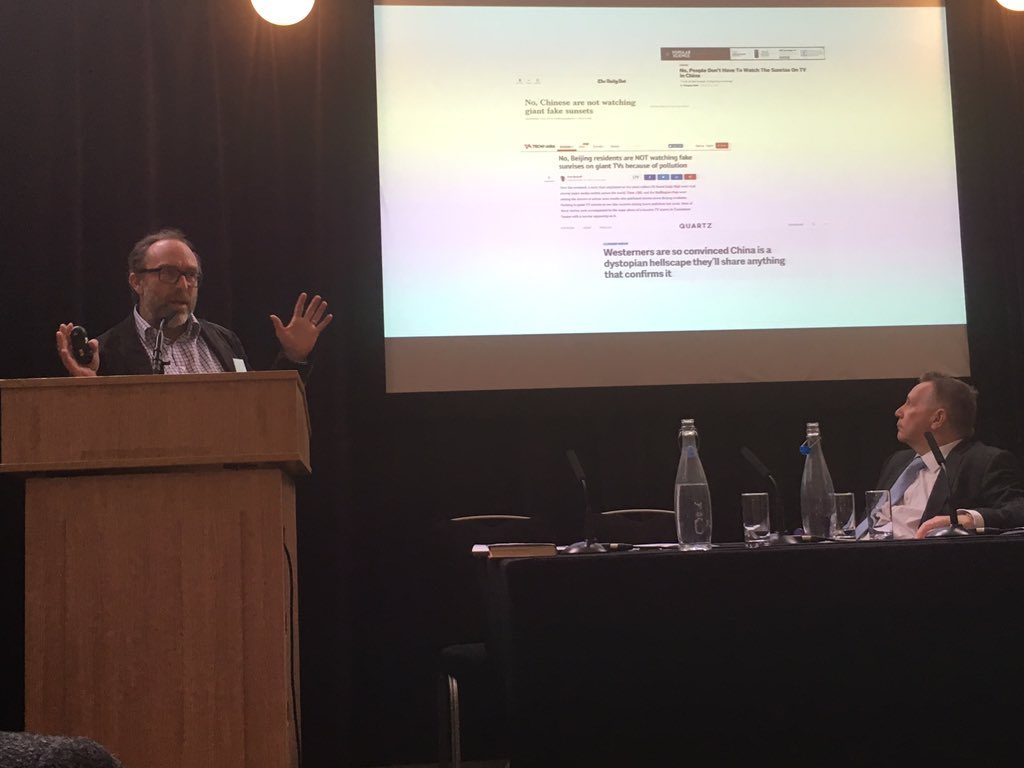

Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales speaking at Westminster Media Forum, April 2018. Credit: Daniel Bruce

“The advertising-only business model has been incredibly destructive for journalism,” said Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales at a Westminster Media Forum event on Thursday 26 April 2018 in London that looked at “fake news”.

“We need to resolve the incentives so that it makes sense and is financially sustainable to do good news,” Wales added.

Wales cited examples of false news stories that had been published on the Mail Online, such as an article featuring a projection of a perfect horizon in Beijing, erected as a way to compensate for the pollution, which proved fake, and a story claiming the Pope supported Donald Trump. He said the Daily Mail of 20 years ago was different. While not what he would choose to read, he thinks there is a place in the media landscape for tabloids, but one running fake news is “a quantum leap we should be very concerned about”.

Suggesting alternatives to advertising-only models, Wales said the Guardian’s donation request box (which he admitted he had consulted on) was an excellent example of how a media organisation can earn money without compromising standards. Meanwhile, a total paywall was very beneficial for some media, in particular financial media, with those readers valuing inside knowledge on the markets, though it would not suit all (the Guardian’s Snowden files, for example, were information he said he would want everyone to be able to access at the same time).

Wales’s concerns about the advertising-only, clickbait-style media models were echoed by others throughout the conference. Drawing an impressive panel of industry experts across media, law and tech, they all united in the view that while fake news meant a myriad of things to many different people, and was not something new, it was nevertheless problematic. Mark Borkowski, founder and head of Borkowski PR, spoke of the 19th-century great moon hoax and how “everything is different and everything is the same” before adding: “The speed at which we expect to get information, without proper fact-checking, is a plague.”

Nic Newman from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism proposed different ways for media to gain more trust, of which “slowing down” was one. Richard Sambrook, former director of global news at the BBC and now director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff University, said the rise in the number of opinion pieces over evidenced-based journalism was because they were cheaper to commission.

Better education about what constitutes good quality, reliable media was another solution proposed.

“Audiences need better education and sensitivity around algorithms,” said Kathryn Geels, from Digital Catapult.

Katie Lloyd, who is development director at the BBC’s School Report and who runs workshops around the country educating school children into news literacy, said there was a sense of urgency and confusion when it came to the topic and that teachers feel like it really needs to be taught.

“Young people are on the one hand savvy and on the other not so much and need extra help,” said Lloyd, adding that of those children she had interacted with, most knew what fake news was in principle, but not how to spot it.

“When we started talking to teachers they said they didn’t have the tools and the skills to teach it,” she added, tapping into a point raised by head of home news and deputy head of newsgathering at Sky, Sarah Whitehead, who said media education was just as important for older people as it was for the young, as the world of online was not the domain of only one group.

Lloyd also explained that diversity was essential when it came to who was delivering news as people were more likely to trust news from those they could relate to. This was in response to an audience member saying they had spoken to school children who expressed that they respected news on Vice over the BBC. Lloyd agreed that it was essential for news organisations to have a wide range of people in terms of age and background. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1524822984082-ad9d065c-d104-5″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Apr 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Daphne Caruana Galizia, the Maltese investigative journalist who was assassinated in October 2017, had numerous lawsuits pending at the time of her murder.

Around the world, big business and corrupt politicians are using threats of legal action to silence journalists and other critics — including NGOs and activists.

Usually this starts with a letter threatening expensive proceedings unless online articles are rewritten or removed altogether, and demanding an agreement not to publish anything similar in the future. The letters often tell the recipient that they cannot even report the fact that they have received the letter.

This process is known as a SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation). SLAPPs are designed to intimidate and silence critics by burdening defendants with huge legal costs. The purpose of SLAPPs is not to win the case. They are vexatious and are designed to eat up time and resources. They are a way to harass and intimidate journalists and others and dissuade them from reporting.

SLAPP suits are a particular problem for independent media outlets and other small organisations. They are financially draining and can take years to process. Faced with the threat of a lengthy litigation battle and expensive legal fees, many who receive SLAPPs are simply forced into silence.

Don’t let them silence you

Index believes that by encouraging journalists and media outlets to talk more openly about these threats, we can begin to put an end to the use of these vexatious lawsuits that threaten democracy.

We support an initiative by members of the European Parliament for a new directive to tackle SLAPPs.

We also know that getting such changes takes time. But it can be done. In the United States, 34 states have enacted laws to combat SLAPPs. California, which adopted its anti-SLAPP legislation in 2009, enables defendants to sue the original plaintiff for malicious prosecution or abuse of process.

In 2015 Canada passed the Protection of Public Participation Act, which aimed to implement a fast-track review process to identify and end vexatious lawsuits.

In the meantime, there are some steps that all journalists can take to help put an end to this practice.

1. Know you are not alone

Journalists from Albania to Japan have received such letters. In Malta, for example, The Shift News website received a letter late last year from law firm Henley and Partners demanding an article be removed. Henley and Partners also stated that the letter was not to be made public.

Daphne Caruana Galizia, the Maltese investigative journalist who was assassinated in October 2017, had numerous lawsuits pending at the time of her murder. She was being sued by Pilatus Bank, a Maltese-based financial institution she frequently criticised. The lawsuit was filed in the USA and dropped following the killing.

Other Maltese media groups, faced with legal threats, have complied with Pilatus Bank’s requests, and deleted and amended articles in their online archives. Pilatus denies any wrongdoing.

In the UK, Appleby, the firm associated with the Paradise Papers, is threatening legal action against the Guardian and the BBC, demanding they disclose any of the six million Appleby documents that informed their reporting and seeking damages for the disclosure of what it says are confidential legal documents.

2. Tell others if you receive a letter

Speak to someone you trust. This could be a colleague at your place of work, your local union or a representative from a nonprofit organisation working in your country or region. Nonprofit organisations and others working in the field of journalist safety include:

Article 19

Committee to Protect Journalists

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom

European Federation of Journalists

International Press Institute

Index on Censorship

Reporters Without Borders

SEEMO

A major fear when receiving a SLAPP letter from a large law firm can be a sinking feeling that you might indeed have something wrong with your story. This casts a long shadow of self-doubt and can prevent journalists even from discussing the letters with each other within the same newsroom.

If you receive these legal threats, discuss them with journalists from other publications who are working on similar stories. This is often the only way to find out that the subject of your investigations is trying to shut down the public discussion systematically. “Discovering that pattern is not only a story in itself, but critically important in helping journalists work together to defend themselves,” says investigative reporter Matthew Caruana Galizia.

3. Report it

If you work in one of the countries covered by the project, you should report such threats to the Index on Censorship Mapping Media Freedom platform, which documents threats to media freedom. Index works with other organisations to raise the worst cases with the Council of Europe so that the council can raise cases directly with the governments concerned.

When you document these threats on Mapping Media Freedom, you help to show that they exist and are a problem for journalists and the public, who are robbed of their right to know. Once we have that documentary evidence, we can push harder for a change in legislation. We believe that the number of threats would speak for themselves, if everyone in the countries we cover reported them.

4. Know your rights

Get expert legal advice but remember that not all lawyers are the same. There are lawyers who are experienced in dealing with SLAPPs. For example, the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom has a legal team that can advise on SLAPP lawsuits and Doughty Street Chambers has an International Media Defence Panel who regularly assist journalists and NGOs faced with these kinds of threats.

Have you received a SLAPP letter? Let us know. Spreading the word about this cases is important in tackling the problem. The more we can document the extent of this issue, the easier it will be to address it. Please let us know by contacting Joy Hyvarinen, Head of Advocacy, at [email protected]. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1523875014232-cb75410f-355e-4″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 May 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

It has been hailed as the damp squib to end damp squibs. The let down of let downs. The mother, the pearl of non-stories. Prince Charles’s “black spider” letters to various government ministers including the prime minister Tony Blair over eight months between 2004 and 2005 have elicited barely an OMG! or a WTF?, but many, many, mehs.

“Where’s the crazy stuff about homeopathy?”, we mumble. “Isn’t there supposed to be some stuff about talking to vegetables, or converting to Kaballah? Aliens? Surely some crop circles?”

Nothing. Or at least nothing worth shaking a divining rod at. One mention of herbal medicines. A hat tip to the Patagonian toothfish and the “poor old albatross”. Lots and lots of impressive detail about agricultural policy.

If anything, having scanned the letters I found myself thinking more highly of Prince Charles than previously. He clearly knows his stuff (or at least has had the good sense to employ someone who knows their stuff) and is genuinely concerned for the farming and fishing sectors.

That is not to say I am comfortable with the existence of these letters. I am a dyed-in-the-wool, though realistic, republican. That is to say, I sincerely disagree with monarchy in any form, but realise there’s not much point in going on about it in the UK. Most people seem reasonably happy with the archaic, arcane set up of the British monarchy. They’re not doing much harm, really, and doesn’t the Duchess of Cambridge have lovely hair? And none of it really matters.

Except that it does matter. The weirdness of the entire set up was exposed after the birth of Princess Charlotte in April. Royal correspondents openly spoke of her assumed lifelong role as second fiddle to her brother, George, who will one day be king.

The BBC did that thing where it reminds you that it is a state broadcaster, informing subjects about how the newborn had brought joy to the entire nation. I am not yet sufficiently misanthropic to be displeased by the birth of a child, but the whole thing had the feeling of the celebration of a successfully completed pagan ritual.

I sometimes wonder if it’s different if you were raised with this stuff: if the British are immune to the oddness of it all.

Times journalist Hugo Rifkind, a writer I admire and generally believe to be right about pretty much everything, confused me with a column after the Supreme Court’s decision that the letters should be published in which he suggested that those who wanted the letters published were guilty of taking the prince too seriously: “[The letters are] the late-night rages of Mr Angry of Highgrove,” Rifkind wrote. “They’re the green ink letters to the press. In a sane and sensible nation, they wouldn’t matter at all.”

The problem is that this isn’t a sane and sensible nation. It is a nation where, purely by birth, Charles has a constitutional role to play. In a republic, the adult first-born of a president could sent whatever letters they wanted, and we’d leave them to it. In a monarchy, you cannot just be the child of a head of state: if that role depends on lineage, then it follows that Charles, while not head of state himself, still has power. It is one thing for a head of state to have regular meetings with her prime minister, but another for her son to throw his weight around on specific policy issues, even if it is all relatively boring stuff. If the monarchy is essentially meaningless and impotent, then scrap it. If not, well, it scrapping is even more urgent.

The government must also take its share of the blame for the fiasco that led to a 10-year legal fight with The Guardian at an estimated cost of £400,000. Why such determination to block the publication of a few letters on farming? Why the panic?

One supposes that they worried not just about the monarchy (former Attorney General Dominic Grieve suggested that the release of the letters would hamper Charles’s future ability to govern), but also about the implications: freedom of information gone wild. If a newspaper can demand to see correspondence from the heir to the throne, where does it all end?

Tony Blair claimed that one of his biggest regrets in government was the introduction of the Freedom of Information Act, which he claimed hampered candid conversations at cabinet level. I have some sympathy with this viewpoint, but I think the benefit of FOI has outweighed any negatives.

But now, with the publication of these old letters, ministers fear they will lose control of the freedom of information process. Hence attempts to strengthen a blanket ministerial veto on freedom of information requests. This on top of the exemption to FOI for senior royals introduced in 2011, in response to the black spider case. It’s a regressive step in an age where we keep being told of the need for open government. But that’s the mess monarchy has got us in to.

We’re not even a week into the new government, and already alarm bells are ringing over freedom of speech (with the government’s extremism plans) and freedom of information. The next few months and years will see bitter wrangling between government and civil libertarians.

If only we knew someone who would be sure that his concerned letters to ministers would be given full attention.

This column was posted on 14 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Jul 2014 | Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, European Union, News and features, Statements

When Europe’s highest court ruled in May that individuals had a ‘right to be forgotten’ many were quick to hail this as a victory for privacy. ‘Private’ individuals would now be able to ask search engines to remove links to information they considered irrelevant or outmoded. In theory, this sounds appealing. Which one of us would not want to massage the way in which we are represented to the outside world? Certainly, anyone who has had malicious smears spread about them in false articles or embarrassing pictures posted of their teenage exploits, or even criminals whose convictions are spent and have the legal right to rehabilitation. In practice, though, the ruling was far too blunt, far too broad brush, and gave far too much power to the search engines to be effective.

At the time of the ECJ decision, Index warned that the woolly wording of the ruling – its failure to include clear checks and balances, or any form of proper oversight – presented a major risk. Private companies like Google – no matter how broad and noble their advisory board might be on this issue – should not be the final arbiters of what should and should not be available for people to find on the internet. It’s like the government devolving power to librarians to decide what books people can read (based on requests from the public) and then locking those books away. There’s no appeal mechanism, no transparency about how Google and others arrive at decisions about what to remove or not, and very little clarity on what classifies as ‘relevant’. Privacy campaigners argue that the ruling offers a public interest protection element (politicians and celebrities should not be able to request the right to be forgotten, for example), but – again – it is hugely over simplistic to argue that simply by excluding serving politicians and current stars from the request process that the public’s interest will be protected.

We are starting to see some of the (high profile) examples of how the ruling is being applied by Google. The Guardian’s James Ball reported on Wednesday that his newspaper had received an email notification from Google saying six Guardian articles had been scrubbed from search results.

“Three of the articles, dating from 2010, relate to a now-retired Scottish Premier League referee, Dougie McDonald, who was found to have lied about his reasons for granting a penalty in a Celtic v Dundee United match, the backlash to which prompted his resignation,” Ball wrote. “The other disappeared articles are a 2011 piece on French office workers making post-it art, a 2002 piece about a solicitor facing a fraud trial standing for a seat on the Law Society’s ruling body and an index of an entire week of pieces by Guardian media commentator Roy Greenslade.”

Similarly, the BBC was told that the link to a 2007 article by the BBC’s Economics Editor, Robert Peston, had also been removed.

Neither The Guardian nor the BBC has any form of appeal against the decision, nor were the organisations told why the decision was made or who requested the removals. You may argue – as some have done – that Google is deliberately selecting these stories (involving well-known journalists with large online followings) as a kind of non-compliant compliance to prove that the ruling is unworkable. Certainly, a fuller picture of the types of request, and much more detailed information about how decisions are arrived at, is essential. You can also point to the fact that it is easy to find the removed articles simply by going to a search engine’s domain outside Europe.

The fact remains that this ruling is deeply problematic, and needs to be challenged on many fronts. We need policymakers to recognise this flabby ruling needs to be tightened up fast with proper checks and balances – clear guidelines on what can and should be removed (not leaving it to Google and others to define their own standards of ‘relevance’), demands for transparency from search engines on who and how they make decisions, and an appeals process. If search engines really believe this is a poor ruling then they should make a clear stand against it by kicking all right to be forgotten requests to data protection authorities to make decisions. The flood of requests that would be driven to these already stretched national organisations might help to focus minds on how to prevent a ruling intended to protect personal privacy from becoming a blanket invitation to censorship.

This article was posted on 3 July 2014 at indexoncensorship.org