6 Oct 2023 | News and features, Opinion, Ruth's blog

This week is Banned Books Week. It should come as no surprise that the topics of censorship, banned books and cancelled authors are a regular theme of discussion at Index on Censorship. In fact we are the UK partner of the global coalition against banned books. The banning of books has repeatedly proven to be a key tool in the arsenal of tyrants and repressive regimes. Control of information and the need for one dominant narrative always leads despots to ban and even burn books. It’s been true throughout history and as much as that concerns me (and it does – a lot) – what worries me more is how pervasive the banning of books is becoming across more democratic countries and what that means for enlightened societies and their peoples.

I truly struggle to comprehend the rationale behind the banning of a specific text or author.

Words can be challenging, thought-provoking and yes, of course, they can even be hateful and inciting. But the answer, surely, is to argue back, to find different authors, to debate and win an argument – not to ban, not to cancel and definitely not to remove from the shelves of our libraries.

The editor in chief of Index, Jemimah Steinfeld, asked the team to write about their favourite banned books as part of the campaign. And as you will have seen I wrote about Judy Blume, one of my favourite authors as a child, I find it ludicrous that anyone would seek to ban books which help young people come to understand their own sexuality or their personal relationships with faith.

But I could have written about a dozen other authors whose words have shaped my worldview but yet inspired such hate and fear that others have sought to ban them. The works of George Orwell were key to helping me develop my own politics – 1984 and Animal Farm confirmed my lifelong commitment to social democratic politics and inspired my personal political campaigns against those on the extremes. Yet these works have been banned repeatedly and not just in repressive regimes but also in some US school districts, unbelievably for being pro-Communist (it really would help if people read the books before they sought to ban them…)

And as a Jewish European woman my politics are grounded, for better or worse, in understanding the horrors of the Shoah. As a student of history I, of course, believe that we must understand our history so that we aren’t destined to repeat it. So the banning of Anne Frank’s diary and the graphic novel Maus by Art Spielgelman, is completely beyond my comprehension. The crucial importance of both of these books isn’t just the subject matter – but the fact that they bring the horrors of a very dark period of our history to life in a format which is accessible to all – including young people. What is there to ban? Unless your real goal is to rewrite Jewish and European history?

Books are the light, they drive challenge and change. They feed our minds and ensure that societies move on and develop. They educate, inform and entertain, even when they are wrong. There are books that I have considered to be of no value, books which I have considered to contain dangerous views and books which I consider to be hateful. But there is no book so dangerous that I don’t think it should be available in an academic library, available to study.

And if you believe on freedom of speech – then that’s the least you should believe too.

5 Oct 2023 | Uncategorized

Beijing Coma – Ma Jian

In the lead up to the Beijing Olympics, when China was on a global charm offensive, Ma Jian’s book Beijing Coma was published. Through the central character Dai Wei, a protester who was shot in Tiananmen Square and fell into a deep coma, Ma presented the other side of the country, an insecure nation afraid of its past and struggling with its present. Ma stated that he wrote the book “to reclaim history from a totalitarian government whose role is to erase it”. I raced through it, went to several book talks he gave and, given the epic proportions of the novel, even enquired about buying the film rights. They were available but I was told that was because few studios would dare take on a work so confronting. To this day the book remains banned in China and no film of it has yet to be made. We are the worse off for that. Jemimah Steinfeld

Are you there God? It’s me Margaret – Judy Blume

As the only child of an amazing single parent, books were a core feature of my childhood. A trip to the library was a joy and visits to the bookshop were a special treat. Getting lost in the pages of a book every night was my happy place and my favourite author as a teenager was Judy Blume. Blume writes beautifully and takes the reader on a journey of exploration of a teenage mind – helping you realise you aren’t alone in being challenged by new experiences and feelings. While from an Index perspective I should say that my favourite book was the one most banned – Forever (which I loved), my absolute favourite was actually Are you there God? It’s me Margaret. As the only Jewish kid at my school I related to Margaret’s internal conflict and her personal relationship with G-d. Blume remains a personal heroine and every effort to ban her books confirms why the work of Index on Censorship is so important. Ruth Anderson

Lady Chatterley’s Lover – DH Lawrence

I had to read DH Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover at school. I hated it. But I did enjoy the ironies that the attempted prosecution of it for “obscenity” totally undermined the state of the obscenity laws at the time and the court case reaffirmed art’s freedom to say pretty much anything it liked, as long as it was judged to be of literary merit (whatever that means). Those who tried to suppress the book only succeeded in fanning the flames of public interest exponentially, beyond who might otherwise have read it without all the hoo-ha and salacious interest whipped up around it. Public interest was the other marker of whether the book should be permitted, so in bringing the prosecution it rather ensured the inevitable failure of the case. The trial has also been highlighted as the start of societal values changing and ushering in the more permissive 1960s. None of this impacted on DH Lawrence, since he’d been dead for 30 years. Publishers had self-censored by holding off publication until Penguin Books took the plunge and British society was probably never the same again. Now, if only a book could have such a societal impact in the 21st century… David Sewell

The Satanic Verses – Salman Rushdie

The Satanic Verses was the subject of a fatwa issued by the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989, which called for the assassination of its author, Salman Rushdie. The novel is Rushdie’s masterpiece: a comic take on the life of Muhammad that also wraps in the British Indian immigrant experience, Bollywood, Sikh separatism and Hinduism. Its ambition is vast and it deserves to be celebrated as one of the greatest novels of the 20th century. Its legacy will live well beyond the regime which forced its author into hiding. Martin Bright

Spycatcher – Peter Wright

I was at university in London when Peter Wright’s Spycatcher was first published and Margaret Thatcher’s government banned it. Wright was a former assistant director of MI5, who was annoyed about the security service’s pension arrangements and decided to blow the whistle over its shadier activities in order to recoup some money for his retirement in Australia. In the 1980s, the workings of the security services were shrouded in secrecy and the book caused huge ripples with its stories of Soviet moles and the then advanced technologies that were being used to spy on Britain’s ‘enemies’. I still remember reading the first chapter and finding out that a nondescript building around the corner from my university department I passed every day was used by MI5 for its covert operations. As the book was not banned in Australia or Scotland, its contents gradually leaked and Thatcher’s government was forced to admit defeat and the book ban was dropped. Mark Stimpson

The Handmaid’s Tale – Margaret Atwood

Look on the shelves of certain school districts in Texas, Michigan and Florida and you’ll find an empty space where The Handmaid’s Tale used to be, after book challenges led to its removal. Atwood’s most famous book might have been published in 1985, but it still has the power to scare self-appointed censors today. The graphic novel, too, is just as excellent and just as hated by censors. In the dystopian Gilead patriarchal structures are taken to the absolute extreme. A woman’s body is not her own – she is judged by her capacity for baby-making. Even her vocabulary is closely monitored. But the way this society was created is even more concerning, with events in the novel inspired by real-world happenings. It’s a book worth reading again and again – it hit home differently when I was a wide-eyed student to how it does now that I’m a mother, and still sends the same chill in a 2023 context. Katie Dancey-Downs

To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

Harper Lee’s classic 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird explores complex themes of race, justice, and humanity, bringing a degree of warmth to heavy subject matter by using the perspective of child protagonist Scout Finch to invoke a sense of innocence, even while tackling difficult topics. Although the book is considered a modern classic, it has been subject to bans and challenges due to its use of profanity, racial slurs, and adult themes. The language and subject matter may make it an uncomfortable read for some, but the overriding message of tolerance and morality is both important and necessary. Daisy Ruddock

Animal Farm – George Orwell

There’s always a book you read that, when you reflect back on, has made an impression on your whole life. For me it was Animal Farm by George Orwell. I first read the book as a teenager and it made me think about the meaning behind the role of governments and the issues of right and wrong, greed and the corruption of power. When I watched the world news and saw the power and restrictions that states placed on their citizens, a book published in 1945 showed me how the world turns and how little change there can be without true democracy. Cathy Parry

His Dark Materials trilogy – Philip Pullman

The His Dark Materials Trilogy by Philip Pullman made its way to me through my grandmother. This was how I often got the books that have stuck with me nearly two decades later. I wonder whether she knew what she did would be so frowned upon by those in the US states who took offence to its apparent “anti-Christian” message? His Dark Materials is glorious collection of young adult books, which snuck in complex messages without patronising the readers. In fact, it challenges and provokes the readers in a manner that sent my teenage brain racing. Also how can you not love a polar bear wearing armour? Nik Williams

The Bell Jar – Sylvia Plath

The Ireland that I was born into was a cold house for women. There was no access to abortion, no divorce and marital rape had only recently been outlawed. Since then, public opinion has been reshaped and laws have been liberalised, largely as a result of ordinary women speaking out about their personal experiences. That’s why The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath is important. It’s a rare example of a canonical work about the life of a young woman as told in her own words. The semi-autobiographical novel, which was previously banned in Ireland and remains banned in some US states, is a coming-of-age story following a young woman at odds with 1950s US society. It challenges the conventional roles of women and explores the difficult, and still tabooed, subject of mental illness. Jessica Ní Mhainín

28 Jul 2023 | News and features, Opinion, Ruth's blog, United States

In a world of online book shopping most of us rarely consider what we’re able to buy, or what books are available from the library. But there is nothing more important in the world of freedom of expression than access to the written word.

Literature can be an escape from reality. It can provide space to dream and to challenge and the best of literature can challenge our perceptions of the status quo. Of course there are bad books as much as there are good books, but each and every published work adds something to our collective understanding of the world around us. That’s why a democracy should cherish the written word and consider libraries as cathedrals of learning and opportunity. The banning of books is for the unenlightened and should be challenged wherever it happens.

And that’s why it is so shocking that 1,648 titles are banned across the United States at the moment, according to PEN America, in their recently updated list of banned books. Many of these books relate to sexuality and LGBTQ+ experiences, and some challenge historical realities, such as segregation and class, or race and history. With these books banned, not only are authors literally being cancelled but minority communities are prevented from seeing characters like themselves in the literature that they read.

The most commonly banned book in the USA at the moment is Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe. What does this say to young people who are questioning their own identity when books which explore the very things that they are currently experiencing are banned?

As a Jewish woman and an anti-racist activist I find the concept of banning books abhorrent. Only those political leaders who are scared of people can possibly think it’s acceptable to ban the written word and make reading an illicit or illegal activity.

I was lucky as a child. I had an enlightened mum who thought there was little else more important than me reading, although I did resent getting the books about my favourite toys rather than the actual toys (yes mum I am still upset I never had a My Little Pony!). But looking at the list of Banned Books PEN America has published I’m disconcerted to see so many of those books I loved as a child banned, including several by Judy Blume and The Handmaid’s Tale by Index patron Margaret Atwood.

Freedom to read is as crucial an element of freedom of expression as freedom to create.

Censorship doesn’t protect children and young people. Reading about gender and sexuality isn’t going to make them go and have sex, or change who they might later choose to have sex with. Just as reading about Afghanistan doesn’t make a child a victim of war or reading about slavery in the USA a slave. Instead reading about those issues can make a young person more compassionate, more understanding of others and more open to new ideas. It generates empathy and gives us all a more informed and confident community who understand pain and anguish as well as our collective history. That is the society I want to live in.

And in the spirit of Barack Obama, who just released his own summer reading list in support of anti-book banning efforts, might I recommend you check out some of those wonderful titles on the list. Together let’s fight book bans.

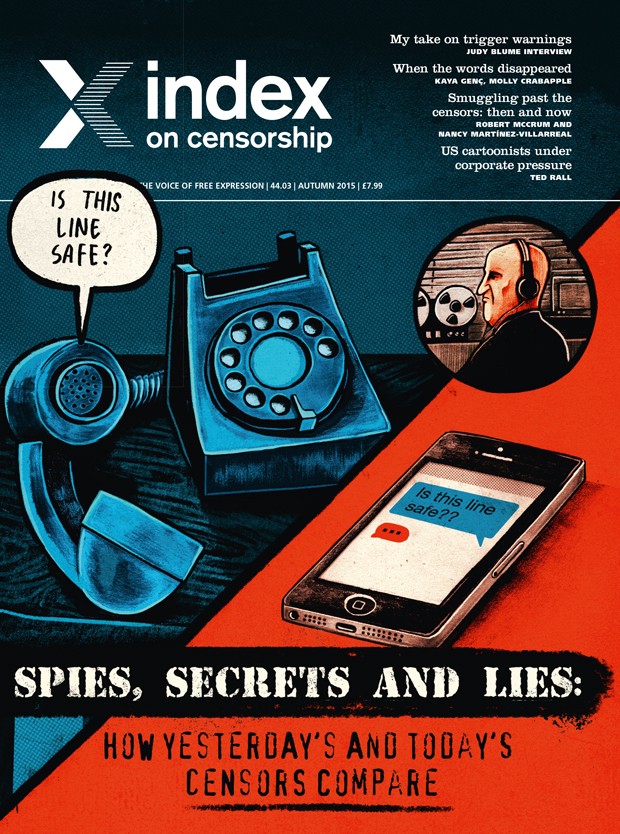

16 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

Judy Blume (Photo: Elena Seibert)

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.

“Why did you kill the pet turtle?” The question took author Judy Blume by surprise on a recent US book tour. The child asking it was referring to a novel first published in 1972, Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing, where Dribble, the pet turtle, is accidentally swallowed by the protagonist’s younger brother. “I’d never heard that complaint before,” Blume told Index on a recent trip to the UK. “People found it funny before, but now I can expect animals-have-feelings-too complaints. Those sorts of questions strike you as funny, but it’s awful too. It’s the adults behind them that are the problem.”

Blume, who has sold 80 million books and been translated into 32 languages, has nothing against turtles, or indeed children’s attachment to pets. But she talks of the “new, very protective” approach to reading that she is seeing more and more. “It’s the job of a parent to help children deal with unexpected things that happen,” said the Florida-based writer, best known for her teen titles. “I often get letters saying, ‘We didn’t like it when this thing happened in your book, so we’re not going to read any of them again.’”

By tackling coming-of-age issues, including sex and puberty, she has experienced various cries of outrage along the way, as well as outright bans by some schools and libraries. In 2009, her publisher even had to send her a bodyguard, after she was deluged with hate-mail and threats for speaking out in support of Planned Parenthood, a US pro-choice group. Five Judy Blume books feature in the 100 most frequently challenged list (1990 to 1999), compiled by the American Library Association, which tracks attempts to ban or censor literature, often by US school boards.

Like many people, I grew up with Judy. I was 11 by the time I had devoured most of her back catalogue. I remember a battered paperback of Forever – the infamous teen sex novel – being passed around my class like contraband, although all our parents and teachers must have known we had it. Her writing about periods was far more enlightening than anything we were taught at school. I still remember the nurse who came into our class and frightened the hell out of us by waving a super-size tampon in the air. “My mum has those!” one school friend said proudly. Her mum was French. I was sure mine didn’t mess with such things.

A US website, Flavorwire, recently compiled a list of “awkward Judy Blume moments” from people’s youth. There was one where a local librarian lent her eight-year-old grandson the novel about a girl’s first period and he wept at the sheer horror of it. There was another about a nine-year-old who had a public tantrum and screamed “Censorship!” at the top of her voice when told she was “not ready” for Judy. Perhaps the most enlightening, however, was the person who admitted trying to get Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret removed from the library because she thought it questioned the existence of God. “I didn’t read it until years later, far past the time when my fundamentalism had lapsed,” she confessed, inadvertently playing a part in the long tradition that sees the most vocal criticism of books coming from those who haven’t read them.

“I’ve always said censorship is caused by fear,” Blume told Index, while on tour to launch her latest book In the Unlikely Event. As a board member of the National Coalition Against Censorship in the US, she has long spoken with passion about her views on the freedom to read, and against books being censored.

Among the most recent children’s books to be targeted in the US are Jeanette Winter’s The Librarian of Basra and Nasreen’s Secret School, which are based on true stories from Iraq and Afghanistan, respectively. Parents from Florida’s Duval County created a petition in July to object to the books references to Islam and war.

“I don’t use age ratings. There’s no reason why someone who wants to, can’t read it. I don’t believe in saying books are for certain age groups,” said Blume, when asked, at a recent UK event at King’s Place, London, if she thought her newest book, written for adults, should be restricted to readers of a certain age.

If censorship had an agony aunt, it would be Blume. Throughout her long career, she’s tackled the big issue openly and without judgement. “Am I being a censor?” a mother asked her recently, after confessing she omitted a section of Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing when she read it to her children. It was a segment where a father is left in charge of his two sons and makes a real hash of it by not knowing how to handle them. “The mother decided not to read that part to her own boys, because she didn’t want them to know how other dads are,” said Blume. “That’s your choice. But my advice is read it all. Talk about it, laugh about it. Say: ‘Aren’t we glad our dad is different?’ No, it’s not censorship. It’s your decision. But are you going to do them any favours by trying to protect them?”

And then comes the thing that makes Blume “very, very upset”: trigger warnings. These are cautions put on books or reading lists to warn of potentially upsetting content, and they are becoming a growing practice at US colleges. Blume only came across the term recently, but instantly took it very seriously. “Why do college students need to be warned that what they are about to read might make them feel bad? These are 20-year-olds, but they need a professor to warn them? What kind of education is that? It makes me crazy.”

The author, who was listed by the US Library of Congress in the living legend category of writers and artists in 2000, also expressed concern about hearing of writers being “dis-invited” from US schools and universities for things they have written or said. “This can be over one incident in a 400-page book,” she said. “I thought the idea of education was to exchange ideas and discuss. How we learn from one another?” Nonetheless, she’s optimistic that this fearful attitude can be fought against. She has already seen professors and teachers standing up to it.

One thing Blume adamantly doesn’t want to see is a return to 1980s America, which was the worse period she has witnessed for freedom to read, and when controversial books were stripped out of classrooms. She believes there has been a return from the precipice of the Reagan era, yet there are still attempts to exert too much control. She referred, very enthusiastically, to The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie, which has also caused a stir and was pulled from the curriculum in Idaho schools. What’s the problem with it I ask? “The language, the sexuality, all things related to life as a teenage boy. It’s like saying it’s a bad thing to be a teenage boy!”

“It’s the kids’ right to read,” she said resolutely as our conversation came to a close and she prepared to continue her whirlwind tour. It’s a mantra she’s been repeating for decades. At 77 and still as dynamic as ever, she shows no sign of stopping anytime soon.

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.