18 Jun 2025 | Americas, News, United States

For many casual listeners, Bruce Springsteen’s song Born in the USA sounds like a glorious patriotic celebration of being American.

Yet listen beyond the upbeat chorus and you discover the dejected life story of a Vietnam veteran who has returned from the war and found it difficult to fit in, readjust to home life and find work.

You can assume that President Donald Trump hadn’t previously picked up on these nuances but now that someone has pointed it out to him, he’s mad as hell.

Born in the USA came out in the middle of 1984 – the year that the eyes of the world were on the country for the Olympics Games in Los Angeles.

It seems that former President Ronald Reagan and his campaign team misinterpreted – either inadvertently or otherwise – the meaning of the song. Reagan name-checked Springsteen on the campaign trail but the rocker later distanced himself from the Republicans.

Springsteen has since used his music to focus on the struggles of the working class and has been more closely aligned with the Democrats, throwing his support behind John Kerry, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama.

Whether President Trump was aware of the song’s meaning or not, he did not fail to understand the meaning of the comments the Boss made during his current world tour, which opened in Manchester this month.

Introducing his 1999 song Land of Hope and Dreams in Manchester, which he had previously played at the inauguration of Joe Biden, he said: “In my home, the America I love, the America I’ve written about, that has been a beacon of hope and liberty for 250 years, is currently in the hands of a corrupt, incompetent and treasonous administration. Tonight, we ask all who believe in democracy and the best of our American experiment to rise with us, raise your voices against authoritarianism and let freedom ring!”

If that message wasn’t clear enough for Trump, he carried on ahead of playing the song House of a Thousand Guitars.

He told the crowd: “The last check on power after the checks and balances of government have failed are the people, you and me.”

“It’s in the union of people around a common set of values now that’s all that stands between a democracy and authoritarianism. At the end of the day, all we’ve got is each other,” he said before launching into a stripped-down version of the song on acoustic guitar and harmonica.

Before launching into his song My City of Ruins, a paean to his home town of Asbury Park In New Jersey, he said that the norms of democracy were being eroded. “There’s some very weird, strange and dangerous shit going on out there right now.”

“In America, they are persecuting people for using their right to free speech and voicing their dissent,” he said. “This is happening now.”

He went on: “They’re rolling back historic civil rights legislation that has led to a more just and plural society.

“They are abandoning our great allies and siding with dictators against those struggling for their freedom. They are defunding American universities that won’t bow down to their ideological demands.

“They are removing residents off American streets and, without due process of law, are deporting them to foreign detention centres and prisons. This is all happening now.

“A majority of our elected representatives have failed to protect the American people from the abuses of an unfit president and a rogue government. They have no concern or idea for what it means to be deeply American.”

He signed off with a message of hope: “The America l’ve sung to you about for 50 years is real and, regardless of its faults, is a great country with a great people. So we’ll survive this moment. Now, I have hope, because I believe in the truth of what the great American writer James Baldwin said. He said, ‘In this world, there isn’t as much humanity as one would like, but there’s enough.’ Let’s pray.”

Trump had certainly got the message by this point. He took to his Truth Social platform to call Springsteen “highly overrated”.

“Never liked him, never liked his music, or his Radical Left Politics and, importantly, he’s not a talented guy – Just a pushy, obnoxious JERK, who fervently supported Crooked Joe Biden, a mentally incompetent FOOL, and our WORST EVER President, who came close to destroying our Country,” he posted.

He then went on to threaten Springsteen.

“This dried out ‘prune’ of a rocker (his skin is all atrophied!) ought to KEEP HIS MOUTH SHUT until he gets back into the Country…Then we’ll all see how it goes for him!”

So much for the “free speech” that Trump can’t stop talking about.

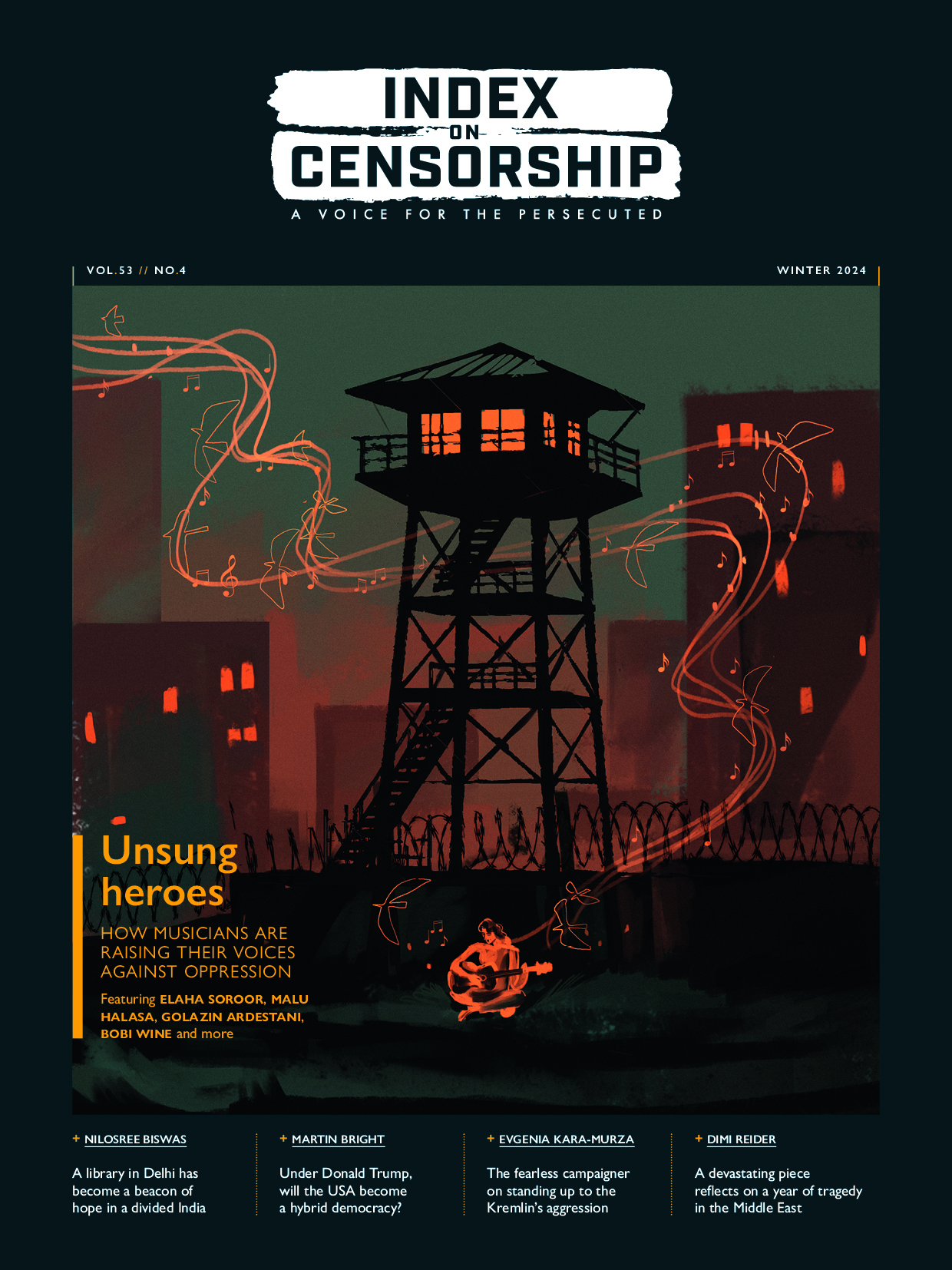

Volume 53, Issue 4 of the print edition of Index on Censorship looked at how musicians are raising their voices against oppression. Read more about the issue here. The issue was published on 12 December 2024.

6 Feb 2025 | Afghanistan, Asia and Pacific, News, Volume 53.04 Winter 2024

This article first appeared in Volume 53, Issue 4 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Unsung Heroes: How musicians are raising their voices against oppression. Read more about the issue here. The issue was published on 12 December 2024.

When the Taliban seized power in Kabul in August 2021, they soon began searching people’s homes for items they deemed to be immoral. Waheedullah Saghar, the head of the music department at Kabul University, had to destroy all of his musical instruments before they were found. Among his collection were special items he’d bought during his time in India, such as a tanpura – a traditional folk stringed instrument.

“It was too risky to keep instruments at home,” he told Index. “Many of my colleagues also felt forced to destroy their instruments, and we disposed of the broken pieces in the garbage to protect ourselves.”

He was denied access to his university and received an official notice from the Taliban that all musical activities in Afghanistan would be prohibited in future.

“It’s very strange, because one day we were honourable, respectable people of our city,” he said. “Then just one day later we became victims and as if we should be punished, because we were musicians. It was very painful and very difficult.”

Saghar and his colleagues were granted asylum in Germany in 2021, and he is currently based in New York on a year-long placement, where he is keeping the culture of his home country alive by teaching university students about Afghan and Indian classical music.

“We had to find a solution for our situation,” he said. “Staying in Afghanistan in that critical moment was not an option because our lives were in danger.”

His story is similar to those of many musicians who have been either forced to leave or forced to abandon their livelihoods. Musicians in the country live in fear of discrimination, humiliation, torture, imprisonment, sexual violence in the case of women and even death. According to the Associated Press, the family of folk singer Fawad Andarabi accused the Taliban of executing him near his home in a mountain province north of Kabul in 2021.

Since their return in 2021, the Taliban have waged a war on music, claiming that it causes “moral corruption”. This approach mirrors their reign between 1996 and 2001, when music was also strictly prohibited. According to figures from its own Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, the group has destroyed more than 21,000 musical instruments over the past year, including traditional items such as tabla drums and rubabs, a type of lute which is Afghanistan’s national instrument.

After their takeover of Kabul, the country’s public radio station, Radio Afghanistan, was swiftly rebranded Voice of Sharia, and music was removed from radio and TV stations, replaced with religious chanting.

Afghans play the dambora at a music festival in Bamyan province in 2017. Photo by Xinhua / Alamy

The Taliban’s use of chanting shows that there is hypocrisy in their extremism, Saghar says. They are sung without instruments, to inspire patriotism and instil their ideology.

“The Taliban don’t seem to understand what music truly represents or its role in society,” he said. “They claim that music is haram (“forbidden”) in Islam, without considering its broader meaning and significance. Music is an inseparable part of human life and is even integrated into aspects of Islamic practice.

“For example, the Quran is recited using musical scales, known as maqams in Arabic, and the Taliban themselves sing taranas – songs composed in Afghan musical scales. However, they overlook these nuances, and they are mainly opposed to musical instruments.”

Since the Taliban’s return, the move towards cultural censorship has gradually worsened, said Ahmad Sarmast, who is the founder of the Afghanistan National Institute of Music, an exiled music school now based in Portugal.

Three years after their takeover, the Taliban announced their “vice and virtue laws”, which have been internationally condemned by human rights groups and the UN. These put in writing the banning of music, said Sarmast, as well as the restriction of women singing or reading aloud in public. This is in addition to the chilling stipulation that women must not speak or show their faces outside their homes.

Cultural bans have since been extended to the wider creative industries, such as filming and photography. The new morality laws prescribe that news media cannot publish images of living things, and TV stations across the country are gradually being closed and converted to radio stations as a result, according to a report from the London-based news site Afghanistan International.

“It’s not just the ban of music or the destruction of musical instruments – it’s a direct attack on the cultural heritage of Afghanistan, and on the freedom of expression of the Afghan people,” said Sarmast.

His orchestral school, which teaches classical Afghan as well as classical and modern Western music, has been “on the Taliban’s hit list” for a decade, he told Index, and endured suicide bombing attempts and targeted attacks even before the group came back into power. Despite the international “whitewashing” of Taliban 2.0, he knew the organisation was “not capable of being changed”.

“We knew that when the Taliban came, our days would be over,” he said.

In a similar way to Saghar’s university department, his music school was “treated like a military barracks” when the Taliban returned. The campus was vandalised, students and faculty were denied entry, property was removed and its bank account was seized.

“Afghanistan was suddenly turned into a silenced nation,” said Sarmast.

Musicians who have been granted asylum tend to be those with a public profile and strong international connections, or those from wealthier backgrounds. Others sold everything they could and took up low-paid jobs, such as selling street food, to survive, Sarmast explained.

One female violinist spoke to Index anonymously about her experiences. She was previously a music teacher but now cannot get a job because she doesn’t have legitimate qualifications beyond her musical education, which is now worthless.

She is currently in hiding and has had to move house several times to avoid being found out as a former musician. She has applied for asylum in Europe, but hasn’t yet been accepted.

“We don’t have a peaceful life. We have to be hidden,” she said. “No one should know that we used to make music. If the Taliban find out, they will kill us.”

Life is particularly treacherous for female musicians. This didn’t start when the Taliban came back into power, but it has worsened, says London-based Afghan singer Elaha Soroor. She told Index that gender discrimination from the fallout from the Taliban’s previous reign made her situation untenable.

“There was a patriarchy, this system, this way of looking at women’s lives – it’s always been there,” she said. “But the Taliban is the worst form of patriarchy. The foundation was there, but people were changing slowly [after their earlier fall], and things were becoming more normal.”

Singer-songwriter Elaha Soroor left Afghanistan in 2010, and now lives in the UK. Photo by Elaha Soroor. Photo by Elaha Soroor

Soroor, who is of the persecuted Hazara ethnic group, was one of the first female musicians to perform in public after the fall of the Taliban in 2000, and appeared on the reality TV show Afghan Star in 2008. She faced death threats, harassment and violence because of her public profile, including from male family members. When an anonymous person uploaded a fake pornographic video of her to YouTube, the violence escalated, and she fled Afghanistan in 2010, seeking asylum in the UK in 2012.

Whilst society was still restrictive, there was more freedom for musical expression then, she said. Bands played at weddings, “music travellers” would walk around the streets with percussion instruments and people loved listening to music.

“You’d go to a taxi [and] everybody’s listening to music at a loud volume,” she said. “It was mainly Afghan pop music from the ’60s and ’70s, new music, Bollywood, Turkish, Arabic and Hindustani.”

She believes that the Taliban’s draconian laws are a way of limiting free thought.

“Musicians, artists, they open up new doors and new ideas. They have this power of entering someone’s subconscious. The Taliban are scared of the power of art, because it can spark new ideas in someone’s mind, and change their way of thinking,” she said.

Now that she’s out of the country, she believes it is her role as an exiled musician to help keep Afghan music alive. In October, she released a new female liberation song titled Naan, Kar, Azadi! (Bread, Work, Freedom!), which she sings in her mother language, Farsi. It features other exiled female Afghans who have spoken out against the Taliban’s oppressive rule, including rapper Sonita Alizadeh. On Instagram, Soroor dedicated the song to “our sisters in Afghanistan as they continue to fight for their rights… in the face of adversity”.

“I feel like the artists who are outside Afghanistan… should be more proactive, create more and stay connected with the story of Afghanistan,” Soroor said. “So at least, if people cannot produce art inside, we should continue producing it outside and export it there [through the internet]. So we keep the flame alive.”

Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey, who produced Soroor’s latest track, is director of performance at Oxford University’s St Catherine’s College, and an academic specialising in orchestral music in Afghanistan. She is working with exiled Afghan musicians to write the first book on orchestral music in the country.

She says that while there is an “absolute ban on music”, its enforcement is likely “uneven”. It’s possible that, in less policed areas, people still listen to music and “engage in their traditional music practices” at home, but professional music-making has certainly been brought to a standstill, which will have long-term impacts on the country’s musical heritage.

“You can’t work – there are no weddings, no parties,” she told Index. “So you have people’s musical knowledge and skill-sets that are probably atrophying. Then they’re becoming impoverished because they don’t have alternative work opportunities.” This has lowered the “social status” of musicians, she said, to historically what it would have been when it was intertwined with “vices” such as alcohol and drug use.

She is particularly concerned about traditional musicians, who she says have been overlooked by European asylum schemes. These have typically given preference to schools making orchestral music – or “Western” music – as they have stronger diplomatic ties with international orchestras, and their students are often better educated with stronger English language skills.

Music made using instruments such as the rubab, the tanbur and the dholak could be lost. She is calling for Germany, which has already established asylum schemes, to set up an Institute of Afghanistan Traditional Music, which could become an international hub for the art form and could help to “potentially get more people out of the country to teach”.

The Afghanistan National Institute of Music is now based in Portugal. Photo by Jennifer Taylor

Artists who made “modern” music, such as rock and pop, also remain stranded in the country. One singer-songwriter and guitar player spoke to Index anonymously. He taught himself the guitar after practising on his father’s dotar. His income stream from music has completely stopped. While he sees music “as a way for great social and cultural change, rather than for money making”, that too has been curtailed.

Having a public profile as a musician is now “almost equal to signing my death certificate”, he said. He has endured threats and physical attacks, and the situation has severely impacted his mental health. “I spend every day with worry and every night with fear, and sometimes I jump from sleep,” he said. “The mental problems that have been created for me are sometimes unbearable. I am always worried about being arrested, killed or tortured.”

Prior to 2021, he would perform for events like International Women’s Day. He hopes that one day girls and women can “study freely and play music, and not be deprived of their basic rights”.

“The absence of music and art has caused freedom of expression to disappear, creativity in culture and art to decline, and national and cultural identity to be weakened,” he said.

Those who have fled Afghanistan have been torn away from their home country, but are still beating the drum for progress and equality. Sarmast, of the Afghanistan National Institute of Music, says that the international music community must work together to raise awareness of the cultural destruction and “gender apartheid” that is happening, and put pressure on the Taliban to restore human rights, of which he believes access to music is one.

As Afghan musicians live in the shadows, those in exile continue to raise awareness of their plight. But there is a real risk that the rich musical heritage of the country will be forever silenced if the world doesn’t continue to campaign for its right to exist.

5 Feb 2025 | Iran, Middle East and North Africa, News, Volume 53.04 Winter 2024

This article first appeared in Volume 53, Issue 4 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Unsung Heroes: How musicians are raising their voices against oppression. Read more about the issue here. The issue was published on 12 December 2024.

In around 2009, Golazin Ardestani was preparing to go on stage in Tehran. The venue was sold out. She and her university classmates had been through months of rehearsals for their traditional concert and had followed all the rules: they had their songs cleared by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, the lead singer was male, the musicians would be seated on the floor and everyone was dressed appropriately, including the correct hijab protocols. And yet, as Ardestani – who goes by the stage name Gola – walked towards the stage, she was told: “No, you can’t perform with them. No female musician can go on stage tonight.”

She stood at the side of the stage and watched her friends perform without her, clutching the formal permission papers which should have allowed her to sing, and which had been wilfully ignored. This is just one of the heartbreaking memories she has of being a female musician in Iran.

A few years later, Ardestani left Iran for good. Now in her 30s, she is based between Europe and the USA, where she creates music that speaks out against the regime. In 2018, she founded her own record label, Zan Recordings, so that she could finally release music on her own terms.

Ardestani was born in Isfahan, in Iran. She taught herself to yodel as a child and grew up in a house filled with a mix of the traditional Persian music favoured by her parents, and the Iranian and Western pop smuggled in by her older siblings, whose musical preferences were inspired by their desire for freedom.

“My teenage years were full of those stolen moments listening to forbidden songs on satellite,” she told Index over email. “Music, and especially female performers, gave me a sense of freedom that was completely absent on our heavily censored government TV.”

Growing up, Gola had never seen a woman on an Iranian stage. At age 19, fed up with trying to conform to traditional norms and still being prevented from singing, she joined some friends and a group of three sisters to create Iran’s first girl band, Orchid.

They wanted to challenge the narrative of female singers being “provocative”, and to resist patriarchal and authoritarian forces. Behind their music was a deep understanding of the history of Iranian music from before the Islamic revolution of 1979, when female singers like Googoosh and Qamar-ol-Moluk Vaziri had been celebrated and were free to perform to mixed audiences.

Orchid was only allowed to perform for female audiences, who had to remain seated. Gestures or movements that could be interpreted as dancing were strictly forbidden. The performers themselves had to avoid showing emotion on stage.

“There were female morality police at the end of each row, watching us and the audience,” Ardestani recalled.

The memory of those performances, in front of thousands of women, is still vivid.

“It was such a powerful experience that I remember making a promise to myself that night: that I would sing, I would sing solo, and I would one day sing for a mixed audience,” she said. “I held onto this vision of a day when our fathers, brothers, husbands and sons could feel proud of the women on stage.”

Whilst in Iran, Ardestani was arrested three times by the morality police, experiences which she said shaped her music and her determination to keep fighting.

The first occasion was when she was just 16, when she was arrested because her hijab wasn’t covering the front of her hair. She sat terrified in a cell and sang to distract herself. A woman shouted at her: “Shut up, close your mouth, shut your ugly voice!”

The last time she was arrested was particularly brutal and was due to the clothes she was wearing. “As they were about to push me into the van, I put on my fighting face, but chaos quickly ensued,” she said. A crowd began to form, and she hit something hard, breaking her arm. With the situation out of control, the police’s superior told her to go home in a taxi.

“All of this because of my ripped jeans, even though I was wearing a long manto [overcoat] and a scarf covering my hair.”

Ardestani considers herself lucky to have escaped alive. Under similar circumstances, Mahsa “Jina” Amini died in custody in September 2022, the moment that sparked the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising.

Iranian singer Golazin Ardestani demonstrating in Washington DC. Photo by Nathan Napolitano

Before leaving Iran in 2011 both to perform without persecution, and to study for a master’s in music psychology in London, Ardestani made a final attempt to plead her case and gain permission to record an album.

“I had to trick my way through the system just to get my foot in the door of the Department of Direction, where the man who granted permissions for male singers worked. But when I finally met him, he wouldn’t even look at me, staring at the floor as he spoke,” she said. She was told that Iran didn’t need a Céline Dion.

Ardestani knew then there was no coming back. “Once I started singing freely, I would lose my home forever,” she said. On the day she left, after Norouz (Persian New Year) in 2011, she decided she would dedicate everything to fighting for change.

“I promised myself that my music would carry the voices of those who can’t be heard,” she said. “There was no way for me to be fully myself as a musician, as a singer or even as a woman. They controlled every aspect of my voice, my body, my agency.”

She knows that she cannot return, and is confident that if she did, she would be arrested and charged with Mofsed fel-Arz, or “spreading corruption on earth”, due to her open challenges to what she calls Iran’s “fabricated religious theocracy”. This charge could carry a death sentence.

The songs she has finally had the freedom to create include Haghame, meaning “It’s My Right”, which is about the freedom to choose whether or not to wear the hijab. Another, Khodavande Shoma, translates to “Your God”, and includes the lyrics: “Your god is sick, it seems – a sick, dangerous criminal. Your religious beliefs, death, and destruction. Your prayers are for murder and blood.”

For female musicians in Iran, freedom is still out of reach. Many women rely on underground scenes, Ardestani told Index, but this comes with its own risks. Posting performances on social media can also lead to arrests, intimidation and the charge of Mofsed fel-Arz.

And censorship does not always respect borders. At a concert in Canada in 2023, designed to support the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, Ardestani was told she could not sing Khodavande Shoma, because the organisers believed it was “attacking people’s religion”. This, she said, is not what the song is about. Rather she is “confronting the twisted version of religion that the Islamic regime has created”.

“I am an Iranian woman fighting for freedom and, specifically, for women’s freedom of choice and speech. Yet here I was, outside of Iran, being told by an organiser – of a concert for freedom, no less – that I couldn’t sing a song in a free country,” she said.

She told the male Iranian organisers that she would sing that song, or not sing at all. They relented.

For every performance Ardestani gives, another song in Iran is silenced. She often posts on social media about the plight of imprisoned Iranian musicians. She condemned the arrest of Zara Esmaeili, who often sang covers of international pop hits in public with her hair uncovered. One social media video showed Esmaeili performing Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black. She was arrested on 25 July 2024, and it is believed that she has not been heard from since.

Ardestani is a huge admirer of Iranian rapper Toomaj Salehi, who won an Index Freedom of Expression Award in 2023. He was first arrested in 2022, and after being detained multiple times and tortured, he was charged with “corruption on earth”, jailed and given the death sentence. The death sentence was dropped after campaigning from prominent musicians and human rights organisations including Index, and Salehi was released in early December.

“It’s unimaginable that a musician, simply expressing himself through lyrics, could be sentenced to death for his art,” Ardestani said. “Iranian music is powerful and resilient; it’s the heartbeat of a people who have been silenced in many other ways. Each song is a form of resistance, a declaration of our existence and our hope.”

As to why Salehi and other musicians are targeted, she has a strong theory: “They know the power of a good song, the potential of meaningful lyrics and the way music can unite people to inspire change.”

For Ardestani now, everything is about fighting for freedom for all – not just in Iran, but globally. She describes music as a way to transform personal struggles into a collective moment. In another of her songs, Betars Az Man, or Fear Me, she sings:

“The butterfly is fleeing its cocoon.

Fear me, as I am that butterfly.

Fear me, as freedom is my voice.”

In her upcoming song Zaloo, she says she will offer her vision for ending theocracy in Iran – a musical call to action. For Ardestani, music is a form of rebellion. And as she told Index, far from being afraid herself: “Those who wish to silence me should be the ones who are afraid.”

See also: Science in Iran: A catalyst for corruption