21 Dec 2015 | Asia and Pacific, China, Magazine, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This is an extract from an article in the Winter 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. You can read the article in full here.

The streets of Dongguan in southern China have been quiet of late. In the past, China’s city of sin would hum to the sound of late-night karaoke bars offering more than just an innocent sing-along. Now these establishments have been forced underground or driven out of business entirely. Their chances of a future are not looking good. On 1 January 2016, new regulations will come into effect that dictate appropriate behaviour for the Communist Party’s 88 million members. As part of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, the new rules explicitly ban the trading of power for sex, money for sex, and adultery – but these are the foundations of business in Dongguan.

“In Dongguan, whose reputation, if not economy, practically rests on its skin trade, I’m told by several sources that the trade remains mostly out of sight nearly two years after a television report [led to]a sweeping crackdown,” said Robert Foyle Hunwick, a writer who has visited the city many times to research his forthcoming book The Pleasure Garden: China’s Hidden World of Sex, Drugs and the Super-Rich.

Dongguan is not the only city suffering from this campaign against smut – it has been lights out for many brothels across China. Nor is this crackdown limited to China’s Communist party members, as the January 2016 regulations imply. Instead, it forms part of a broader crackdown on China’s sex industry that has been underway since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012.

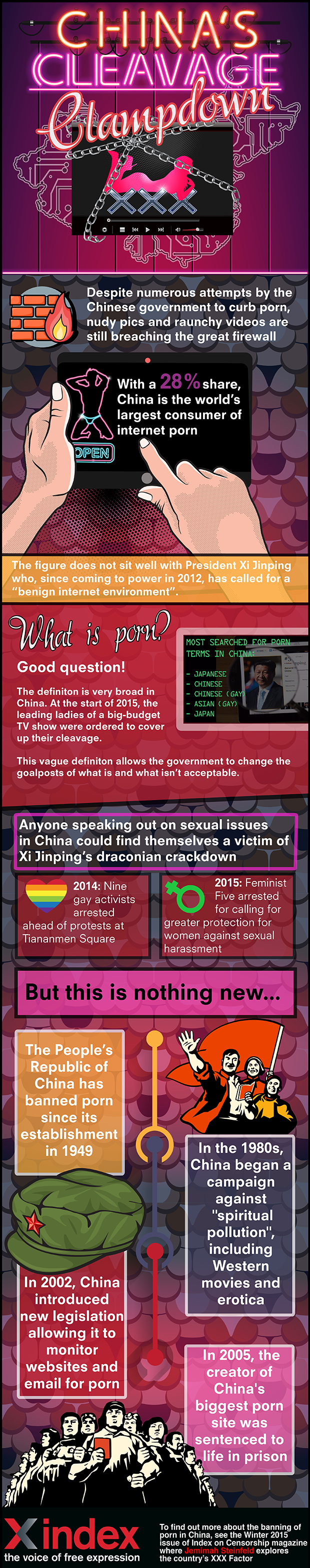

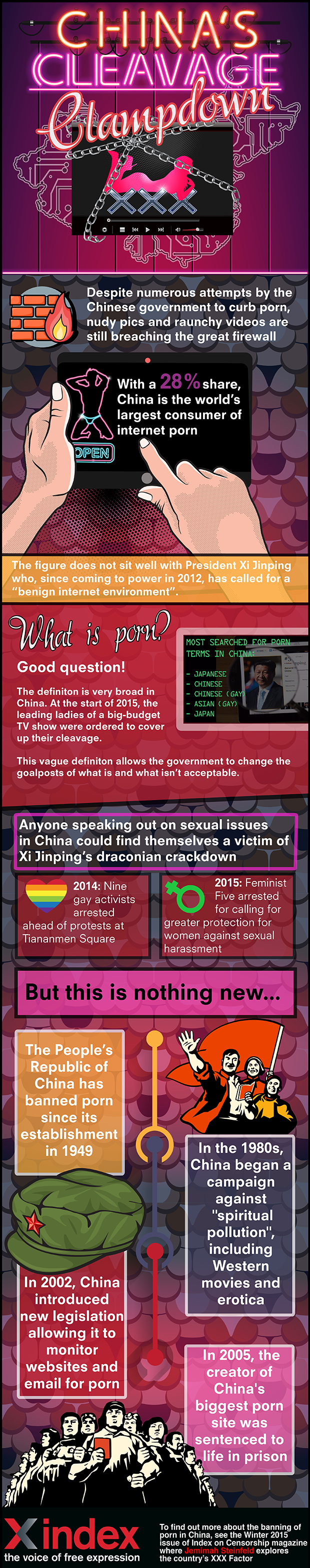

Enemy number one is internet pornography. In the most recent statistics, from 2014, China accounts for up to 28% of the world’s porn consumption, taking the global lead. It’s a statistic that does not sit well with Xi. Shortly into his term in power, he launched his first anti-pornography crusade, calling for a “benign internet environment”. An attempt was made to clear China’s internet of anything verging on pornography. A similar initiative was launched this summer, following the release of a video featuring a couple having sex in a Uniqlo store. It was the usual drill: sites were blocked or removed and anyone caught facilitating the production or distribution of pornography was arrested.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Jul 2013 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

The Prime Minister’s touching belief that he can clean up the web with technology is misguided and even dangerous, says Padraig Reidy

Announcing plans to clean up the internet on Monday morning, David Cameron invoked King Canute, saying he had been warned “You can as easily legislate what happens on the Internet as you can legislate the tides.”

The story of Canute and the sea is that the king wanted to demonstrate his own fallability to fawning fans. But David Cameron today seems to want to tell the world that he can actually eliminate everything that’s bad from the web. Hence we had “rape porn”, child abuse images, extreme pornography and the issue of what children view online all lumped together in the one speech. All will be solved, and soon, through the miracle of technology.

Cameron points out that “the Internet is not a sideline to ‘real life’ or an escape from ‘real life’; it is real life.” In this much he’s right. But he then goes on to discuss the challenge of child abuse and rape images in almost entirely technological terms.

I’ve written before about the cyber-utopianism inherent in the arguments of many who are pro filtering and blocking: there is an absolute faith in the ability of technology to tackle deep moral and ethical issues; witness Cameron’s imploring today, telling ISPs to “set their greatest minds” to creating perfect filters. Not philosophers, mind, but programmers.

Thus, as with so many discussions on the web, the idea that if something is technologically possible, then there is no reason not to do it, prevails. It’s simply a matter of writing the right code rather than thinking about the real implications of what one is doing. This was the same thinking that led to Cameron’s suggestion of curbs on social media during the riots of 2011.

The Prime Minister announced that, among other things, internet service providers will be forced to provide default filters blocking sites. This is a problem both on a theoretical and practical level; theoretically as it sets up a censored web as a standard, and practically because filters are imperfect, and block much more than they are intended to. Meanwhile, tech-savvy teenagers may well be able to circumvent them, meaning parents are left with a false sense of security.

The element of choice and here is key; parents should actively choose a filter, knowing what that entails, rather than passively accepting, as currently proposed by the Prime Minister. Engaging with that initial thought about what is viewed in your house could lead to greater engagement and discussion about children’s web use – which is the best way to protect them.

It is proposed that a blacklist of search terms be created. As Open Rights Group points out, it will simply mean new terms will be thought up, resulting in an endless cat and mouse game, and also a threat of legitimate content being blocked. What about, say, academic studies into porn? Or violence against women? Or, say, essays on Nabokov’s Lolita?

Again, there is far too much faith in the algorithm, and far too little thinking about the core issue: tracking down and prosecuting the creators of abuse images. The one solid proposal on this front is the creation of a central secure database of illegal images from which police can work, though the prime minister’s suggestion that it will “enable the industry to use the digital hash tags from the database” does not fill one with confidence that he is entirely across this issue.

The vast majority of trade in abuse images comes on darknets and through criminal networks, not through simple browser searches. This is fairly easily proved when one, to use the Prime Minister’s example, searches for “child sex” on Google. Unsurprisingly, one is not immediately bombarded with page after page of illegal child abuse images.

As Daily Telegraph tech blogger Mic Wright writes: “The unpleasant fact is that the majority of child sexual abuse online is perpetrated beyond even the all-seeing eye of Google.”

The impulses to get rid of images of abuse, and shield children from pornography, are not bad ones. But to imagine that this can be done solely by algorithms creating filters, blacklists and blocking, rather than solid support for police work on abuse images, and proper, engaged debate on the moral and ethical issues of what we and our children can and cannot view online, really is like imagining one can command the tides.

30 Jan 2013 | Uncategorized

A former CIA officer was sentenced on 25 January to more than two years in prison for leaking official information to the media. John Kiriakou had released the name of a covert officer to a reporter in 2007 in media interviews which were among the first to confirm the waterboarding of detainees, including al-Qaida terrorist Abu Zubaydah. Defenders say the former officer acted as a whistleblower to the CIA’s use of torture to interrogate detained terrorists, whilst prosecutors said his intention was purely to gain fame and status. He pleaded guilty to violating the Intelligence Identities Protection Act in 2012, the first conviction under the law in 27 years. Kiriakou was initially charged under the World War I-era Espionage Act but swapped charges in a plea deal. The deal meant US district judge Leonie Brinkema was restricted to imposing a two and a half year sentence — which she said she would have extended if she could.

Poster for the play Behzti – Gurpreet Bhatti has faced censorship of another play by the BBC

Human rights defender Alaa Abdel Fattah was arrested in Egypt on 29 January for allegedly defaming a judge. The political activist and 2012 Index on Censorship awards nominee was released on bail by Judge Tharwat Hammad on Tuesday, as part of a wider investigation into allegations against private satellite channels. Charges have been filed by 1,164 judges, who complained that TV station workers had invited guests on air who had criticised the judiciary. Abdel Fattah was charged with incitement against the military in October 2011 during the Maspero demonstrations in which 27 protestors were killed.

Playwright Gurpreet Bhatti said that her play scheduled for broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 1 February has had lines removed from the script. During Index on Censorship’s arts conference Taking the Offensive at the Southbank Centre on 29 January, Bhatti told attendees that her play Heart of Darkness had been altered by broadcasters. The episode, due to be played on the Afternoon Drama slot, followed the investigation into the honour killing of a 16 year old Asian girl – a case investigators are told to handle sensitively because of her Muslim heritage. Bhatti’s play Behzti was axed from a Birmingham theatre in 2004 following protests from the Sikh community. The playwright denied the BBC’s compliance department accusations that lines were offensive in Heart of Darkness, saying “we live in a fear-ridden culture.”

Germany’s foreign minister said on 28 January that Russia’s draft bill banning “homosexual propaganda” could harm Russia’s ties with Europe. In a meeting on Monday evening, Guido Westerwelle told Russia’s ambassador in Berlin, Vladimir Grinin, that the law violated the European human rights convention and will harm Russia’s image and relationships within Europe. The draft legislation was passed by the State Duma, Russia’s lower house of parliament, on 25 January and prompted protests by the gay community, including a kiss-in protest by activists which was broken up by police on Friday. The law will ban the promotion of homosexuality amongst children and is alleged to intend consolidation of public support for President Vladimir Putin.

On 28 January, Twitter began censoring porn related searches on its video sharing app Vine yesterday, after a six-second porn clip was accidentally made editor’s pick. Searching for terms such as #sex and #porn came up with no results, but users could still access pornographic content if it had been posted under a different hashtag. The social networking site apologised for circulating the video of a graphic sex act on the app launched last week, blaming the slip-up on a “human error”. Vine was introduced to Twitter as a video programme similar to Instagram, where users can upload six second video loops, some of which proving to appeal to a more adult audience. Last week, Apple banned 500px, a photography app with a section dedicated to nudity, from its app store.

22 Feb 2012 | Digital Freedom, Middle East and North Africa

On 22 February the Cassation Court of Tunis (Tunisia’s highest court of appeal) overturned a verdict ordering Tunisian Internet Agency (ATI) to filter pornography on the internet. The court has sent the case back to the Court of Appeal.

On May, 26, 2011, the Court of First Instance issued a ruling ordering the Tunisian Internet Agency (ATI), to filter X-rated websites. On August, 15, 2011, the ruling was affirmed by the Court of Appeal.

Tunisian free speech advocates fear that blocking access to pornography would be used as pretext to block other content, and would pave the way for a return to internet censorship.

The ATI is technically incapable of undertaking the role of internet censor. This what Moez Chakchouk, CEO of the agency said, in an interview with Index three weeks ago, he said the agency had neither the financial or legal backing to enforce web blocking.

In a press release this afternoon the agency said it will “continue working towards the development of Internet in Tunisia and to act as an IXP (Internet Exchange Point), in a transparent and neutral way towards all”.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]