21 Sep 2016 | Magazine, mobile, News and features, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016 Extras, Youth Board

In the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, The Unnamed: Does anonymity need to be defended?, Index’s contributing editor for Turkey, Kaya Genç, explores anonymous artists in Turkey. In the piece the artists discuss how vital anonymity is in allowing them to complete their more controversial work. The Index on Censorship youth advisory board have taken inspiration from this piece for their latest task, in which they investigate anonymous art around the world.

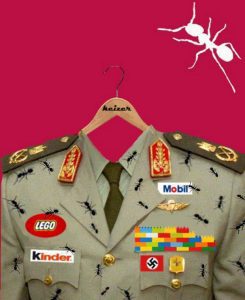

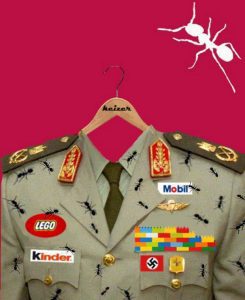

Keizer by Constantin Eckner

Ants feature in Keizer’s work to sybolise “the forgotten ones, the silenced, the nameless, those marginalised by capitalism”. Image: Keizer

Prior to the January 25 Revolution political street art was anything but common in Egypt, yet it has proliferated in public spaces in the aftermath of the revolution. One of the most productive street artists in Cairo is Keizer, who has gained popularity and notoriety in recent years. Like Banksy and other street artists, he uses the well-known stencil technique to empower his fellow countrymen, and people in general, with his thought-provoking work. He likens people to ants, which are featured in most of his graffiti. Keizer explains on his Facebook account that the ant “symbolises the forgotten ones, the silenced, the nameless, those marginalised by capitalism. They are the working class, the common people, the colony that struggles and sacrifices blindly for the queen ant and her monarchy.”

Asked about the reason for protecting his identity, Keizer said: “I am very concerned over my safety and the repercussions of street art which I’ve already had a taste of, especially with this current regime. Including death threats,

Egyptian street artist Keizer has gained popularity in recent years. Image: Keizer

my twitter account was hacked twice. In the past five years of working on the street I’ve been caught once. I came out of it with a few bumps and bruises, nothing major. I consider myself lucky that I came out one day later.

“You can imagine that being caught here is very different than being caught in Europe. There is no proper procedure and that makes you a victim of the person handling you, and the uncertainty of what comes next. Graffiti is a grey area here, they don’t have any definition or classification for it in the books, so they make it up as they go along, taking you for the fear ride. It’s all under vandalism, so they can make it look small or escalate it to exaggerated levels. For instance, you can be dubbed as a political traitor; it can be considered racketeering; they can glue your name to any political movement unpopular with the people…etc.”

Tall walls, low profiles: Icy and Sot by Layli Foroudi

Icy and Sot describe themselves as stencil artists from Tabriz, Iran. As for their identities, they reveal only that they are brothers, born in 1985 and 1991. Their work is created under pseudonyms in countries around the world, including Iran, USA, Germany, Norway, and China, on legal and illegal walls as well as in galleries.

The anonymous duo, who paint on themes like human rights, censorship, and justice, say that charges against artists in Iran make going public risky.

“Pseudonyms help us to keep a low profile,” the brothers explained in an interview with ArtInfo, “Being arrested in Iran is completely different, because they charge you with crimes that you have not even committed, like Satanism or political crimes.”

Their work often uses striking human faces in black and white to make statements about politics and the environment, to call for peace, and to direct messages at the government of Iran. In 2015, Icy and Sot used their art to protest for freedom of expression in Iran, prompted by the arrest and 18-month imprisonment of Atena Farghadani, an Iranian artist who was detained for publishing a cartoon that satirised the Iranian government as animals. In solidarity, they stenciled a tribute piece depicting Farghadani with a backdrop of protesters on a wall in Brooklyn.

Maeztro Urbano’s fight to change a criminal image by Ian Morse.

In the most recent data, Honduras has the highest homicide rate in the world, with 84 intentional homicides per 100,000 people in 2013. The prominence of drug trafficking and ubiquity of poverty does not improve its reputation.

To some Hondurans, their country’s international image has done nothing but hurt citizen’s attempts to improve daily life in the country’s bustling cities and lively cultural centers. Maeztro Urbano and his friends became the face of an urban street art project to disrupt the atmosphere of crime and reveal another side of the country outside of the headlines.

His projects range from adjusting street signs promoting gender equality to vandalising billboards with corrupt politicians, to wall graffiti showing the effect of violence on children. Working his day shifts in the advertising industry, Maeztro Urbano said he wants to contribute more to his country than proliferating consumerism.

“Change should start within society. With each individual,” El Maestro – as he is also called – told The Creators Project. “To have respect for the lives of others, to respect the right to sexual diversity, to a better education.”

“If we don’t change that as a society and as individuals, we will never be able to change as a country.”

Assailants in Honduras have not been very hospitable to those reporting on crime or those wishing to express their identity. Faced with police harassment and shootings from unknown attackers, Maeztro Urbano chooses to wear a mask while he works to spread messages of hope around the country.

Bleeps.gr: Over a decade of political artivism in Athens by Anna Gumbau.

Bleeps.gr is one of Greece’s most prominent street artists, having painted murals on the streets of Athens for over 10 years. Image: Bleeps.gr

“I have been radically oriented to the political discourse, utilising the public sphere, and I am not afraid or discouraged”, Bleeps.gr, one of the most prominent Greek street artists, told Index.

Bleep.gr has been designing murals, that are mostly critical of the austerity policies imposed to Greece, on the streets of Athens for over 10 years. The Greek social turmoil has had a strong influence on his artwork, not only in his scenes, but even in his methods. “I buy very cheap materials and can’t afford those impressive equipment to create a mural”, he said in an interview with Street Art Europe.

Bleeps.gr chooses to use a pseudonym as an attempt to challenge “the institutionalised perception of the identity”, he told Index. While he is not afraid of the state authorities, he points at art institutions, such as galleries, exhibitions and festivals, who reject and exclude his art. “Most of the censorship I have received has come from other artists, especially the ones related to systemic initiatives, who in the past years have removed all of my works from the city center” he said. Greek political street artists often suffer from the exclusion of art galleries and exhibitors; in the summer of 2013, the CRISIS? WHAT CRISIS? street art festival in Athens, which celebrates the value of street art in the current political happenings, invited 20 artists from different European countries but failed to invite any Greek artists.

Nevertheless, Bleeps.gr stresses the fact that the internet “has provided a virtual field of allocation”, and most of the political street art discourse happens there.

Bleeps.gr highlights the mechanisms of such institutions to “absorb street artists” and make them become part of the art “business”, adding: “the majority of them nowadays serve gentrification policies and turn policies and turn political art into a spectacle for tourist pleasure”.

King of Spades by Sophia Smith-Galer.

When it comes to anonymous artists, the art tends to speak far louder than any speculation into the artist themselves. This anonymous artist in Lebanon is no Arab Banksy that lurks tantalisingly close to the limelight; this artist could quite literally be anyone, and the lack of anybody claiming the piece as their own is revelatory of the grave reality of artists in developing countries that test the patience of despots and tyrants.

Despite its tired and no longer relevant label “Paris of the Middle East”, even the dazzlingly artistic city of Beirut, Lebanon, can’t quite get away with hanging something like this banner, depicting the late Saudi Arabian monarch King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz as a brutal King of Spades. Shortly after its creation in 2013, the Lebanese state prosecutor ordered an investigation to reveal the source of these posters after complaints from Saudi Ambassador Ali Awad Asiri.

It seems that nobody got caught, and nor do I particularly want to dwell on what would have happened to the artist if they had. But in the Middle East, such a daring artistic expression must be forbidden fruit in a region of gagged political artistry; demonstrated no better than in this mysterious artist who gambled with the assumed impunity of that gentleman with the bloodied scimitar.

Dede Bandaid by Shruti Venkatraman.

One of Dede Bandaid’s most well known works, a missile target painted in the middle of a large car park, a reference to the Gaza conflict in 2014. Image: Dede Bandaid / Wikicommons

Dede Bandaid is an anonymous Israeli artist who has added colour to Tel Aviv’s streets with thought provoking and politically relevant street art. His artistic career began in 2000 during his compulsory military service, and most of his earlier pieces demonstrated a clear anti-establishment sentiment. His more recent works, following the end of his stint in the military, aim to communicate social and political messages. One of his most well known works is a missile target painted in the middle of a large car park, a reference to the Gaza conflict in 2014.

Dede enjoys using public spaces as a canvas as this approach allows freer and more controversial expression, while also being accessible to and viewable by a larger audience especially when the street art is photographed and its images are circulated online. He also makes use of traditional symbols of peace, like the white dove, and frequently incorporates Band-Aids that represent healing and remedy in his artwork, with “Bandaid” being the pseudonym he signs on all his pieces. Over time, Dede’s style has evolved from stencilling to free-hand painting and collage and he interestingly also exhibits certain pieces in galleries across the world.

Cabbage Walker in Kashmir by Niharika Pandit.

A pheran-clad man walks around with a cabbage on a leash in the neighbourhoods of Srinagar, Kashmir. This performance act that he presents is inspired by Chinese artist Han Bing’s “Walking the Cabbage” social intervention work. While Bing chose to walk the cabbage to reflect on the changing values in the Chinese society, where once cabbage was a subsistence food product but is now only embraced by the poor, in Kashmir, this anonymous artist aims to normalise the cabbage walking to show the absurdity of militarisation in the region. Both the performances employ cabbage as an element of satire to expose the irony inherent in what how elitism and militarisation come to be normalised in societies across the world.

The Kashmiri Cabbage Walker writes on his blog, “I as a Kashmiri am willing to recognise walking the cabbage as part of the Kashmiri landscape but I will never accept the check posts, the bunkers, the army camps, the torture centers, the barbed wire, the curfews, the arrests, the toxic environment of conflict and war, as part of the same.”

This performance artist chooses to remain anonymous as it helps in focusing on the message and not the messenger. The Kashmiri Cabbage Walker says that he represents all Kashmiri lives under militarisation thereby revealing the artist’s identity becomes unimportant here.

Cracked pavements in Budapest by Fruzsina Katona.

Anonymous volunteers have joined the satirial political party the Two-Tailed Dog party (MKKP) to paint cracked pavement on the streets of Budapest. Image: Fruzsina Katona

Anonymity does not necessarily mean that one is trying to hide his or her identity. Sometimes the identity of the person is utterly irrelevant. In Budapest, several anonymous volunteers are painting the streets of the city.

The pavement on the streets of the Hungarian capital are falling apart, ruining the image of the city and endangering those who walk on it. Authorities are known to do very little to fix the problem, but something had to be done. Hungary’s satiric political party, the Two-Tailed Dog party (MKKP) called for action and its artsy, anonymous volunteers started colouring the cracked pavement pieces resulting in dozens of cheerful spots across the city.

Unfortunately, there are some who find quarrels in a straw, and the police were called on the ad-hoc artists while they were peacefully decorating the pavement in a touristic neighbourhood. Now the volunteers are being prosecuted with vandalism.

But we still do not know their identity or how many of them are out decorating. All we know is that now we look at colourful patches of pavements while running our errands, instead of the sad and ugly cracked pavements.

19 Sep 2016 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, mobile, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Does anonymity need to be defended? Contributors include Hilary Mantel, Can Dündar, Valerie Plame Wilson, Julian Baggini, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Maria Stepanova “][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2”][vc_column_text]

The latest issue of Index on Censorship explores anonymity through a range of in-depth features, interviews and illustrations from around the world. The special report looks at the pros and cons of masking identities from the perspective of a variety of players, from online trolls to intelligence agencies, whistleblowers, activists, artists, journalists, bloggers and fixers.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”78078″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Former CIA agent Valerie Plame Wilson writes on the damage done when her cover was blown, journalist John Lloyd looks at how terrorist attacks have affected surveillance needs worldwide, Bangladeshi blogger Ananya Azad explains why he was forced into exile after violent attacks on secular writers, philosopher Julian Baggini looks at the power of literary aliases through the ages, Edward Lucas shares The Economist’s perspective on keeping its writers unnamed, John Crace imagines a meeting at Trolls Anonymous, and Caroline Lees looks at how local journalists, or fixers, can be endangered, or even killed, when they are revealed to be working with foreign news companies. There are are also features on how Turkish artists moonlight under pseudonyms to stay safe, how Chinese artists are being forced to exhibit their works in secret, and an interview with Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot.

Outside of the themed report, this issue also has a thoughtful essay by novelist Hilary Mantel, called Blot, Erase, Delete, about the importance of committing to your words, whether you’re a student, an author, or a politician campaigner in the Brexit referendum. Andrey Arkhangelsky looks back at the last 10 years of Russian journalism, in the decade after the murder of investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya. Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov looks at how metaphor has taken over post-Soviet literature and prevented it tackling reality head-on. Plus there is poetry from Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky and Russian writer Maria Stepanova, plus new fiction from Turkey and Egypt, via Kaya Genç and Basma Abdel Aziz.

There is art work from Molly Crabapple, Martin Rowson, Ben Jennings, Rebel Pepper, Eva Bee, Brian John Spencer and Sam Darlow.

You can order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: THE UNNAMED” css=”.vc_custom_1483445324823{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Does anonymity need to be defended?

Anonymity: worth defending, by Rachael Jolley: False names can be used by the unscrupulous but the right to anonymity needs to be defended

Under the wires, by Caroline Lees : A look at local “fixers”, who help foreign correspondents on the ground, can face death threats and accusations of being spies after working for international media

Art attack, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Ai Weiwei and other artists have increased the popularity of Chinese art, but censorship has followed

Naming names, by Suhrith Parthasarathy: India has promised to crack down on online trolls, but the right to anonymity is also threatened

Secrets and spies, by Valerie Plame Wilson: The former CIA officer on why intelligence agents need to operate undercover, and on the damage done when her cover was blown in a Bush administration scandal

Undercover artist, by Jan Fox: Los Angeles street artist Skid Robot explains why his down-and-out murals never carry his real name

A meeting at Trolls Anonymous, by John Crace: A humorous sketch imagining what would happen if vicious online commentators met face to face

Whose name is on the frame? By Kaya Genç: Why artists in Turkey have adopted alter egos to hide their more political and provocative works

Spooks and sceptics, by John Lloyd: After a series of worldwide terrorist attacks, the public must decide what surveillance it is willing to accept

Privacy and encryption, by Bethany Horne: An interview with human rights researcher Jennifer Schulte on how she protects herself in the field

“I have a name”, by Ananya Azad: A Bangladeshi blogger speaks out on why he made his identity known and how this put his life in danger

The smear factor, by Rupert Myers: The power of anonymous allegations to affect democracy, justice and the political system

Stripsearch cartoon, by Martin Rowson: When a whistleblower gets caught …

Signing off, by Julian Baggini: From Kierkegaard to JK Rowling, a look at the history of literary pen names and their impact

The Snowden effect, by Charlie Smith: Three years after Edward Snowden’s mass-surveillance leaks, does the public care how they are watched?

Leave no trace, by Mark Frary: Five ways to increase your privacy when browsing online

Goodbye to the byline, by Edward Lucas: A senior editor at The Economist explains why the publication does not name its writers in print

What’s your emergency? By Jason DaPonte: How online threats can lead to armed police at your door

Yakety yak (don’t hate back), by Sean Vannata: How a social network promising anonymity for users backtracked after being banned on US campuses

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Blot, erase, delete, by Hilary Mantel: How the author found her voice and why all writers should resist the urge to change their past words

Murder in Moscow: Anna’s legacy, by Andrey Arkhangelsky: Ten years after investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya was killed, where is Russian journalism today?

Writing in riddles, by Hamid Ismailov: Too much metaphor has restricted post-Soviet literature

Owners of our own words, by Irene Caselli: Aftermath of a brutal attack on an Argentinian newspaper

Sackings, South Africa and silence, by Natasha Joseph: What is the future for public broadcasting in southern Africa after the sackings of SABC reporters?

“Journalists must not feel alone”, by Can Dündar: An exiled Turkish editor on the need to collaborate internationally so investigations can cross borders

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Bottled-up messages, by Basma Abdel Aziz: A short story from Egypt about a woman feeling trapped. Interview with the author by Charlotte Bailey

Muscovite memories, by Maria Stepanova: A poem inspired by the last decade in Putin’s Russia

Silence is not golden, by Alejandro Jodorowsky: An exclusive translation of the Chilean-French film director’s poem What One Must Not Silence

Write man for the job, by Kaya Genç: A new short story about a failed writer who gets a job policing the words of dissidents in Turkey

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: Europe’s right-to-be-forgotten law pushed to new extremes after a Belgian court rules that individuals can force newspapers to edit archive articles

Index around the world, by

Josie Timms: Rounding up Index’s recent work, from a hip-hop conference to the latest from Mapping Media Freedom

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

What ever happened to Luther Blissett? By Vicky Baker: How Italian activists took the name of an unsuspecting English footballer, and still use it today

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1483444808560-b79f752f-ec25-7″ taxonomies=”8927″ exclude=”80882″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

22 Aug 2014 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

Street art from Mohamed Mahmoud Street, Cairo. (Photo: Melody Patry/Index on Censorship)

Before the January 2011 uprising, street art was little known in Egypt. Then came the revolution and with it, an outburst of creativity.

With the fall of the authoritarian regime of Hosni Mubarak, Egyptian artists who had routinely faced censorship restrictions under his autocratic rule, felt a strong urge to break out of the confines of their studios and reclaim public spaces. Young artists in particular, decided they needed bigger canvases for the grand ideas they wanted to convey through their paintings. To celebrate their newfound liberation, many of them took their art directly to the people and onto the streets, expressing their views and opinions on public walls and on the sides of buildings.

Bonded by their shared aspirations for a better Egypt, the young graffiti artists spent long hours working together, creating vivid group murals that told the stories of the revolution in which they had actively participated. The images they produced in the months following the 2011 uprising documented the dramatic changes that were unfolding in the country, the continued unrest ensuring a steady supply of material for them to work with. The artists also spread powerful messages of “equality” and “freedom” that helped shape public opinion, attitudes and values.

“Our murals added colour to the otherwise dull streets and boosted the morale of the people. But as graffiti artists and activists, we also played the role of the ‘alternative critical media,’ telling the untold stories and spreading messages that helped the public better understand what was really happening on the ground,” said graffiti artist Salma Sami, a graduate of fine arts who has also worked as a broadcaster.

An image of Pinnochio on TV, spray-painted on a wall on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, off Tahrir Square, shortly after the fall of Mubarak, was intended to poke fun at state media — for long, a propaganda tool of the ousted Mubarak regime. According to Sami, the mural also “serves as a warning to Egyptians not to believe everything the media tells them”.

Besides being a critical voice, raising awareness and informing the public of the events unfolding in the country, Cairo’s nascent street art movement also helped keep the spirit of the January 25 revolution alive.

“As a woman, I wasn’t accustomed to working in the street and was afraid at first especially after hearing stories of sexual assault incidents in the very neighbourhood where we worked. But once I started working, I felt safe. Working in a group helped us revive the spirit of the revolution, letting go of our fears and uniting behind a common goal,” Sami said.

The street artists successfully managed to break down social barriers of class, religion and gender. They created a close-knit community among themselves but were also accessible to the public.

“Crowds would often gather to watch as we worked and then, someone would volunteer to help. Soon, we would find others joining in. The fact that a lot of our work was painted with roller brushes made it easy for anyone to participate,” Sami told Index.

(Photo: Melody Patry/Index on Censorship)

Like Sami, Bahia Shehab — an art historian and graphic designer — was also very much a part of the street art movement that emerged and developed after the 2011 revolution. Her trademark “no” stencils, spray painted on the walls of Mohamed Mahmoud Street have helped draw public attention to social problems, exhorting Egyptians to take a stand against violence, oppression, and other forms of injustice.

Shehab joined the street art movement nine months after the revolution when she saw an image of a protester’s corpse dumped in a pile of rubbish in her Facebook newsfeed. The gruesome picture, which had gone viral on social media networks, so infuriated her that she rushed to Tahrir Square to express her rage. Her stencilled message “no to military rule” marked the beginning of her “thousand times no” campaign — a series of images decrying torture, sexual violence and other issues she felt strongly about.

Carrying on the idea from her 2010 book — a compilation of “one thousand no-s” in a multitude of Arabic calligraphy styles — she added a range of fiery messages denouncing rights abuses that were committed during the country’s transitional period. ”No to violence and thuggery”, “no to stripping girls” and “no to sectarian divisions” are just a few in her long list of stencilled images.

More than three years after the uprising that toppled autocrat Hosni Mubarak, Shehab says her “old” list is “still relevant” and her concerns “still valid”. She continues to consistently add more “no” messages, saying she is “deeply disappointed” with the turn of events in her country. Among the new additions is a stencil calling for an end to the brutal security crackdown on dissent.

A nationalist fervour sweeping the country has however made it dangerous for graffiti artists to express themselves freely. Those who dare criticise government policies are often accused of being “traitors” and “terrorists” by self-proclaimed “patriots”. Today, while many of the young street artists view former army chief and current president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi as merely the new face of the old military regime, few dare depict him in their artworks. Sisi came to power following the 2013 coup that overthrew Egypt’s first democratically elected president, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi. Several established street artists have chosen to remain anonymous, signing their artworks using nicknames for the sake of their security.

“Working in the street has always been dangerous,” noted Shehab, adding that “the only difference is that the danger now comes from violent ‘patriotic’ mobs supporting the military where before it was from the police.”

But mob violence is not the only danger threatening Egypt’s street art movement. A proposed draft law banning so-called “abusive graffiti art” — if passed — may likely restrict artistic expression and may spell the end of the graffiti tradition, even before it fully emerges. Under the draft law, violators could face a prison sentence of up to four years or a fine of up to 100,000 Egyptian pounds.

The recent alleged murder of one of Shehab’s comrades — 19 year-old graffiti artist and member of the April 6 youth movement Hisham Rizk — has compounded her fears, sending shivers down many spines in Egypt’s artistic circles. Rizk’s body was found in a Cairo morgue last month, a week after his family reported his “mysterious disappearance”. A forensic report concluded that the young artist had died of “asphyxiation by drowning in the Nile River”. Sceptical fellow artists however, believe Rizk’s critical views of the government expressed in his drawings and on Facebook may have instigated a confrontation with security officials that led to his death.

(Photo: Melody Patry/Index on Censorship)

“People don’t always agree with our views and different people interpret our artworks in different ways but at least our murals provide food for thought,” noted Sami who, in early 2012, designed a controversial mural depicting a skull with a military cap, holding a flower between clenched teeth. The image was a fitting portrayal of the brutal military regime that replaced Mubarak after the revolution. The 18-month rule of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) was marred by political turmoil and violence including forced virginity tests performed by the military on female protesters

You can still see Sami’s mural on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, along with many others that are critical of both SCAF and the Muslim Brotherhood. The latter are depicted as sheep, while military men are portrayed as butchers in some of the murals. The colourful artworks are reminiscent of a happier time of free artistic expression and hope — a phase that, some of the artists fear, may well be over.

Yet, both Sami and Shehab remain defiant, saying that neither laws nor intimidation will deter them from the journey they have started. They draw similarities between their art and the 2011 revolution, saying both are constantly shifting and come in waves. Their murals in downtown Cairo have been whitewashed several times with other artists painting over them or adding new images as new events unfold, sparking new ideas. “Sometimes, residents in the area paint over the images if they oppose our views,” said Sami.

“I no longer mind when my work disappears. When that happens, I just tell myself it’s time to design a new stencil and I head straight back to Mohamed Mahmoud Street.”

The Index on Censorship interactive documentary Shout Art Loud explores how Egyptians use graffiti and other art forms to tackle the issue of sexual harassment and violence against women. Watch it here.

This article was posted on August 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org