Preventing protest coverage: How Belarus controls what the public knows

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The winter 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine examines the state of the right of assembly 50 years on from 1968. Kyra McNaughton details how authorities in Belarus police the reporting of protests using data from Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project.”][vc_column_text]

Belarusian police detain Belarus Free Theatre’s Siarhai Kvachonok on Saturday March 25 2017 during protests against Presidential Decree No 3, which imposes a tax on unemployed people. (Photo: Tut.by)

“Europe’s last dictatorship” doesn’t tolerate dissent. The country’s constitution claims to protect freedom of the press, but many laws seem to contradict this.

Independent outlets are constrained by laws in favor of state-run media. Most frequently targeted are Belarus’s independent journalists and Belsat TV, alternatives to the heavily censored state-run Belarusian news. These targeted journalists often fall victim to Belarus’ restrictive regime for press accreditation, a system used by the government to “maintain its monopoly on information in one of the world’s most restrictive environments for media freedom”, according to a report by Index.

“An openly critical stance of the [Belsat TV] towards the authorities of Belarus results in the situation when it is not officially registered in the country and its journalists are pushed beyond the legal system through rules that neither grant them official accreditation, nor recognise freelancers as journalists”, said Andrei Aliaksandrau, deputy director of BelaPAN and editor of the Belarus Journal. “Reporters are subject to administrative prosecution, arrests and fines on ridiculous charges of ‘illegal production of mass media materials’”.

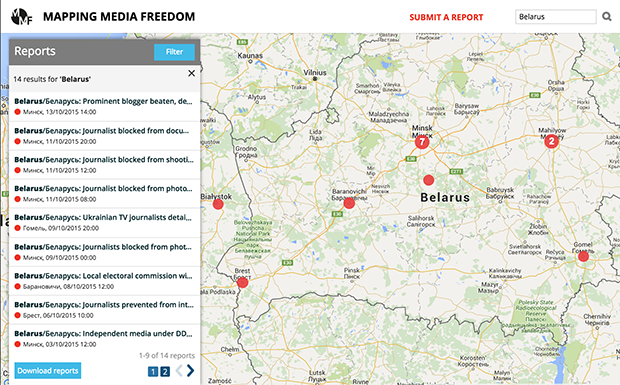

In order to stifle awareness of the public’s unhappiness with the current political climate, the government targets journalists covering protests before, during and after the demonstrations. Index’s Mapping Media Freedom has documented as many as 22 cases since 2015.

“For the past 20 years the authorities in Belarus have been known for their harsh police violence against street protests, including against journalists … After 2011 street protests and mass opposition rallies became rare in Belarus, right until early 2017 when people returned to the streets of Belarusian cities to protest against deterioration of economic situation. The police used brutal force again; and journalists were among those detained”, said Aliaksandrau.

With tactics ranging from detention to assault, Belarusian law enforcement specifically go after independent reporters in an effort to prevent the public from knowing the full extent of protests.

Before

Between March and May of 2017, MMF documented five cases of journalists detained before they were scheduled to cover protests.

Two Belsat TV journalists and one independent journalist were detained twice in one day on their way to cover protests on 18 March 2017. The journalists were first accused of a traffic violation, then later of stealing a car and robbing a bank, according to MMF. The journalists were going to cover one protest in a series nationwide called against a proposed tax.

That same day, four different groups of Belsat journalists were detained in different cities to prevent coverage of demonstrations.

Also on the same day, two Belsat TV journalists were detained during a live broadcast. They were reporting on a possible protest when two police officers arrived. The two were detained without explanation and released hours later.

During

Since 2015 there are 11 documented cases on MMF of journalists being targeted while on site of a protest.

On 25 March 2017, Freedom Day in Belarus, 39 journalists across the country were detained, totalling around 90 detentions alone in the month of March, according to the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ). MMF reports seven of the 30 detained were beaten by police.

After the mass detentions on Freedom Day, 16 journalists were detained the next day during solidarity rallies across the country. Of those detained between both days, some were charged with “hooliganism” and sentenced from five to fifteen days in prison.

In 2015, as independent blogger Viktar Nikitsenka was leaving a demonstration, plain-clothed police officers seized him and dragged him into a bus where he was reportedly beaten. Information and materials were deleted from his phone and camera and his equipment was stolen. He was fined 450 euros.

When Nikitsenka filed a complaint against the officers for unlawful use of force, it was rejected.

After

On 18 March 2017, four Belsat TV crews intending to report on protests were detained in different cities. In one incident, Belsat TV journalist Ales Lyauchuk reported that he and a colleague were stopped by traffic police after covering a protest, then “dragged out of the car [and] brutally assaulted”. The two were reportedly stopped without explanation and held at the station for three hours, their equipment damaged and seized.

“They said that if this goes on, they will shoot us”, Lyauchuk said.

Five days before, video blogger Maksim Filipovich received three separate prison sentences for participating in “illegal” protests. Riot police arrested him at his parents flat, which he livestreamed.

“Targeting journalists who are trying to report on protests is misuse of official powers and it shows how little media freedom there is in Belarus”, said Joy Hyvarinen, Head of Advocacy.

As coverage of protests is censored by targeted the journalists who cover them, freedom of expression both in the form of journalism but also protest is being stifled. Instead of immediately targeting protests, the Belarusian government diminishes the purpose of a protest, since the cause can’t gain attention.

In countries like Belarus where press freedom is protected by the constitution, rulers ignore the law to advance a political agenda.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F%20|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores the 50th anniversary of 1968, the year the world took to the streets, to look at all aspects related to protest.

With: Micah White, Robert McCrum, Ariel Dorfman, Anuradha Roy and more.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship monitors press freedom in 42 European countries.

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified more than 3,700 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1513938526925-22ecd957-f7ad-4″ taxonomies=”19962″][/vc_column][/vc_row]