23 Sep 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Address for response c/o

Campaign for Freedom of Information

Unit 109

Davina House

137-149 Goswell Rd

London EC1V 7ET

The Rt Hon David Cameron MP

Prime Minister

10 Downing Street

London SW1A 2AA

21 September 2015

Dear Prime Minister,

We are writing to express our serious concern about the government’s approach to the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act and in particular about the

Commission on Freedom of Information and the proposal to introduce fees for tribunal appeals under the Act.

It is clear from the Commission’s terms of reference that its purpose is to consider new restrictions to the Act. The Commission’s brief is to review the Act to consider: whether there is an appropriate balance between openness and the need to protect sensitive information; whether the ‘safe space’ for policy development and implementation is adequately recognised and whether changes are needed to reduce the Act’s ‘burden’ on public authorities. The ministerial announcement of the Commission’s formation stressed the need to protect the government’s ‘private space’ for policy-making.1 There is no indication that the Commission is expected to consider how the right of access might need to be improved.

The Commission’s five members consist of two former home secretaries, Jack Straw and Lord Howard of Lympne (Michael Howard), a former permanent secretary, Lord Burns, a former independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, Lord Carlile of Berriew (Alex Carlile) and the chair of a regulatory body subject to FOI, Dame Patricia Hodgson. A government perspective on the Act’s operation will be well represented on the Commission itself.

One of the Commission’s members, Jack Straw, has repeatedly maintained that the Act provides too great a level of disclosure. Mr Straw has argued that the FOI exemption for the formulation of government policy should not be subject to the Act’s public interest test.2 Such information would then automatically be withheld in all circumstances even where no harm from disclosure was likely or the public interest clearly justified openness. Mr Straw has also suggested that the Supreme Court exceeded its powers in ruling that the ministerial veto cannot be used to overturn a court or tribunal decision under the Act unless strict conditions are satisfied.3 He has argued that there should be charges for FOI requests and that it should be significantly easier for public authorities to refuse requests on cost grounds.4 Mr

Straw’s publicly expressed views cover all the main issues within the Commission’s terms of reference. Speaking in the Commons shortly before the Commission’s appointment, the Justice Secretary, Michael Gove, expressly cited Mr Straw’s views with approval saying that he had been ‘very clear

about the defects in the way in which the Act has operated’.5

Another member of the Commission is Ofcom’s chair, Dame Patricia Hodgson. In 2012, when she was its deputy Chair, Ofcom stated that ‘there is no

doubt’ that the FOI Act has had a ‘chilling effect’ on the recording of information by public authorities. One of the Commission’s priorities is likely to be to consider whether there has been such an effect — and whether the right of access should be restricted to prevent it. Ofcom has also

called for it to be made easier for authorities to refuse requests on cost grounds and for the time limits for responding to requests to be increased.6

An independent Commission is expected to reach its views based on the evidence presented to it rather than the pre-existing views of its members. Indeed, in appointing members to such a body we would expect the government to expressly avoid those who appear to have already reached and expressed firm views. It has done the opposite. The government does not appear to intend the Commission to carry out an independent and open minded

inquiry. Such a review cannot provide a proper basis for significant changes to the FOI Act. The short timescale for the Commission’s report, which is due by the end of November, further reinforces this impression. At the time of writing, half way towards the Commission’s final deadline, it has so far not even invited evidence from the public.

The FOI Act was the subject of comprehensive post-legislative scrutiny by the Justice Committee in 2012 which found that the Act had been ‘a significant enhancement of our democracy’ and concluded ‘We do not believe there has been any general harmful effect at all on the ability to conduct business in the public service, and in our view the additional burdens are outweighed by the benefits’. We question the need for a further review now.

We are also concerned about the government’s proposal to introduce fees for appeals against the Information Commissioner’s decisions.7 Under the proposals, an appeal to the First-tier Tribunal on the papers would cost £100 while an oral hearing would cost £600. The introduction of fees for employment tribunal appeals has led to a drastic decrease in the number of cases brought. A similar effect on the number of

FOI appeals is likely. Requesters often seek information about matters of public concern, so deterring them from appealing will deny the public information of wider public interest. On the other hand, fees are unlikely to discourage public authorities from challenging pro-disclosure decisions, so the move will lead to an inequality of arms between requesters and authorities. Given that the Ministry of Justice and the Justice Committee have recently begun to review the impact of employment tribunal fees on access to justice we find it remarkable that this proposal should be put forward before the results of their inquiries are even known.

We regard the FOI Act as a vital mechanism of accountability which has transformed the public’s rights to information and substantially improved the scrutiny of public authorities. We would deplore any attempt to weaken it.

Yours sincerely,

Act Now Training, Ibrahim Hasan, Director

Action on Smoking and Health, Deborah Arnott, Chief Executive

Against Violence and Abuse, Donna Covey, Director

Animal Aid, Andrew Tyler, Director

Archant, Jeff Henry, Chief Executive

ARTICLE 19, Thomas Hughes, Executive Director

Article 39, Carolyne Willow, Director

Belfast Telegraph, Gail Walker, Editor

Big Brother Watch, Emma Carr, Director

British Deaf Association, Dr Terry Riley, Chair

British Humanist Association, Andrew Copson, Chief Executive

British Muslims for Secular Democracy, Nasreen Rehman, Chair

BSkyB, John Ryley, Head of Sky News

Burma Campaign UK, Mark Farmaner, Director

Campaign Against Arms Trade, Ann Feltham, Parliamentary Co-ordinator

Campaign for Better Transport, Stephen Joseph, Chief Executive

Campaign for Freedom of Information, Maurice Frankel, Director

Campaign for National Parks, Ruth Bradshaw, Policy and Research Manager

Campaign for Press & Broadcasting Freedom, Ann Field, Chair

Centre for Public Scrutiny, Jacqui McKinlay, Executive Director

Chartered Institute of Library & Information Professionals, Nick Poole, Chief Executive

Children England, Kathy Evans, Chief Executive

Children’s Rights, Alliance for England, Louise King, Co-Director

CN Group Limited, Robin Burgess, Chief Executive

Community Reinvest, Dr Jo Ram, Co-Founder

Computer Weekly, Bryan Glick, Editor in Chief

CORE, Marilyn Croser, Director

Corporate Watch / Corruption Watch, Susan Hawley, Policy Director

Coventry Telegraph, Keith Perry, Editor

Cruelty Free International, Michelle Thew, Chief Executive Officer

CTC, the national cycling charity, Roger Geffen, Campaigns and Policy Director

Daily Mail, Paul Dacre, Editor; Jon Steafel, Deputy Editor; Peter Wright, Editor Emeritus; Charles Garside, Assistant Editor; Liz Harley, Head of Legal

Debt Resistance UK

Deighton Pierce Glynn, Sue Willman, Partner

Democratic Audit, Sean Kippin, Managing Editor

Disabled People Against Cuts, Linda Burnip, Co-Founder

Down’s Syndrome Association, Carol Boys, Chief Executive

Drone Wars UK, Chris Cole, Director

English PEN, Jo Glanville, Director; Maureen Freely, President

Equality and Diversity Forum, Ali Harris, Chief Executive

Evening Standard, Sarah Sands, Editor

Exaro, Mark Watts, Editor in Chief

Finance Uncovered, Nick Mathiason, Director

Friends of the Earth, Guy Shrubsole, Campaigner

Friends, Families and Travellers, Chris Whitwell, Director

Gender Identity Research and Education Society, Christl Hughes, Legal Consultant

Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, Peter Newell, Co-ordinator

Global Witness, Simon Taylor, Co-Founder and Director

Greenpeace, John Sauven, Executive Director

Guardian News and Media Limited, Gillian Phillips, Director of Editorial Legal Services

Hacked Off, Dr Evan Harris, Executive Director

i, Oliver Duff, Editor

Inclusion London, Tracey Lazard, Chief Executive Officer

independent.co.uk, Christian Broughton, Editor

Index on Censorship, Jodie Ginsberg, Chief Executive Officer

INQUEST, Deborah Coles, Co-Director

Involve, Simon Burall, Director

Johnston Press Editorial Board, Jeremy Clifford, Chairman

Jubilee Debt Campaign, Sarah‐Jayne Clifton, Director

KM Group, Geraldine Allinson, Chairman

Labour Campaign for Human Rights, Andrew Noakes, Director

Law Centres Network, Julie Bishop, Director

Leigh Day, Russell Levy, Head of Clinical Negligence

Liberty, Bella Sankey, Policy Director

Liverpool Echo, Alastair Machray, Editor

London Mining Network, Richard Solly, Co-ordinator

Loughborough and Shepshed Echo, Andy Rush, Editor

LUSH, Mark Constantine, Managing Director

medConfidential, Phil Booth, Co-ordinator

Metro, Ted Young, Editor

Migrants’ Rights Network, Don Flynn, Director

Move Your Money UK, Fionn Travers-Smith, Campaign Manager

mySociety, Mark Cridge, Chief Executive

NAT (National AIDS Trust), Deborah Gold, Chief Executive

National Commission on Forced Marriage, Nasreen Rehman, Vice Chair

National Union of Journalists, Michelle Stanistreet, General Secretary

Newbury Weekly News, Andy Murrill, Group Editor

News Media Association, Santha Rasaiah, Legal, Policy and Regulatory Affairs Director

Newsquest, Toby Granville, Editorial Development Director; Peter John, Group Editor for Worcester/Stourbridge

Nursing Standard, Graham Scott, Editor

NWN Media, Barrie Phillips-Jones, Editorial Director

Odysseus Trust, Lord Lester of Herne Hill QC, Director

Open Data Manchester, Julian Tait, Co-Founder

Open Knowledge, Jonathan Gray, Director of Policy and Research

Open Rights Group, Jim Killock, Executive Director

OpenCorporates, Chris Taggart, Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer

Oxford Mail and The Oxford Times, Simon O’Neill, Group Editor

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals Foundation, Dr Julia Baines, Science Policy Advisor

Press Association, Pete Clifton, Editor in Chief; Jonathan Grun, Emeritus Editor

Press Gazette, Dominic Ponsford, Editor

Prisoners’ Advice Service, Lubia Begum-Rob, Joint Managing Solicitor

Privacy International, Gus Hosein, Executive Director

Private Eye, Ian Hislop, Editor

Public Concern at Work, Cathy James, Chief Executive

Public Interest Research Centre, Richard Hawkins, Director

Public Law Project, Jo Hickman, Director

Pulse, Nigel Praities, Editor

Race on the Agenda, Andy Gregg, Chief Executive

Renewable Energy Foundation, Dr John Constable, Director

Reprieve, Clare Algar, Executive Director

Republic, Graham Smith, Chief Executive Officer

Request Initiative CIC, Brendan Montague, Founder and Director

Rights Watch (UK), Yasmine Ahmed, Director

RoadPeace, Beccie D’Cunha, Chief Executive Officer

Salmon and Trout Conservation (UK), Guy Linley-Adams, Solicitor

Sheila McKechnie Foundation, Linda Butcher, Chief Executive

Society of Editors, Bob Satchwell, Executive Director

South Northants Action Group, Andrew Bodman, Secretary

South Wales Argus, Kevin Ward, Editor

Southern Daily Echo, Ian Murray, Editor in Chief

Southport Visitor, Andrew Brown, Editor

Spinwatch, David Miller, Director

Stop HS2, Joe Rukin, Campaign Manager

Sunday Life, Martin Breen, Editor

TaxPayers’ Alliance, Jonathan Isaby, Chief Executive

Telegraph Media Group, Chris Evans, Editor and Director of Content

The Corner House, Nick Hildyard, Founder and Director

The Independent, Amol Rajan, Editor

The Independent on Sunday, Lisa Markwell, Editor

The Irish News, Noel Doran, Editor

The Mail on Sunday, Geordie Greig, Editor

The Sun, Tony Gallagher, Editor; Stig Abell, Managing Editor

The Sunday Post, Donald Martin, Editor

The Sunday Times, Martin Ivens, Editor

The Times, John Witherow, Editor

Transform Justice, Penelope Gibbs, Director

Transparency International UK, Robert Barrington, Executive Director

Trinity Mirror, Simon Fox, Chief Executive; Lloyd Embley, Group Editor in Chief; Neil Benson, Editorial Director Regionals Division

Trust for London, Bharat Mehta, Chief Executive

UNISON, Dave Prentis, General Secretary

Unite the Union, Len McCluskey, General Secretary

Unlock Democracy, Alexandra Runswick, Director

War on Want, Vicki Hird, Director of Policy and Campaigns

We Own It, Cat Hobbs, Director

Welfare Weekly, Stephen Preece, Editor

WhatDoTheyKnow, Volunteer Administration Team

Women’s Resource Centre, Vivienne Hayes, Chief Executive Officer

WWF-UK, Debbie Tripley, Senior Legal Adviser

Zacchaeus 2000 Trust, Joanna Kennedy, Chief Executive

38 Degrees, Blanche Jones, Campaign Director

4in10 Campaign, Ade Sofola, Strategic Manager

1 www.gov.uk/government/speeches/freedom-of-information-new-commission

2 The Rt Hon Jack Straw MP, oral evidence before Justice Committee, Post-Legislative Scrutiny of the Freedom of Information Act, 17 April 2012, Q.344. www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmjust/96/120417.htm

3 BBC Radio 4, Today programme, 14 May 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/may/14/court-exceeded-its-power-in-ordering-publication-of-charles-memos-straw. The Supreme Court’s ruling related to the use of the veto to block the release of Prince Charles’ correspondence with ministers in response to a request by the Guardian newspaper

4 Oral evidence to Justice Committee, 17 April 2012, Q.355 & Q.363. www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmjust/96/120417.htm

5 House of Commons, oral questions, 23.6.15, col. 754, www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmhansrd/cm150623/debtext/150623‐0001.htm#15062354000032

6 Ofcom, February 2012, Written evidence to the Justice Committee, Post-legislative Scrutiny of the Freedom of Information Act, Volume 3, Ev w176-177. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmjust/96/96vw77.htm

7 The Government response to consultationon enhanced fees for divorce proceedings, possession claims, and general applications in civil proceedings and Consultation on further fees proposals

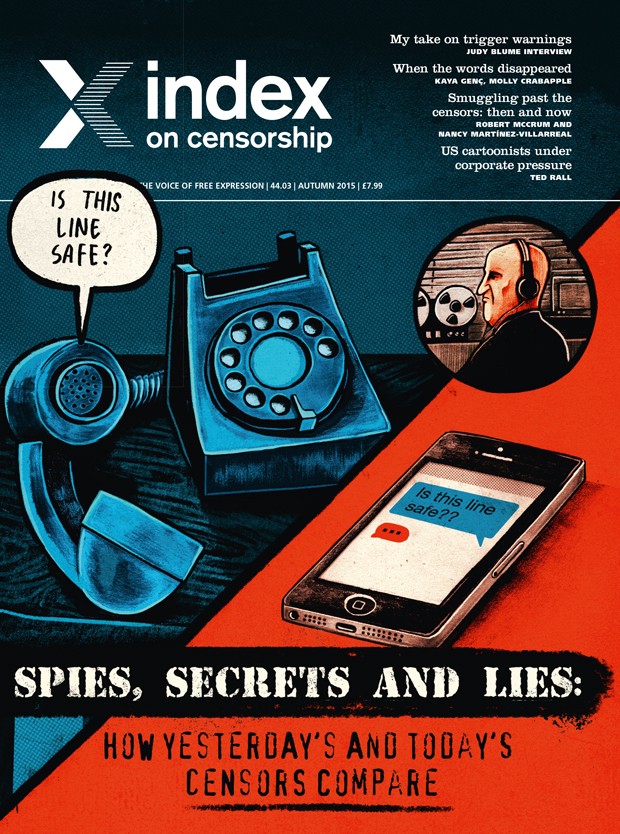

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

Today the bulk of the media in the Balkans has “been bought by people with no history in, or understanding of, the media business; they promote narrow interests of their owners or new political elites; sometimes without even pretence of objectivity,” said Kemal Kurspahic, former editor of Oslobodjenje, an independent newspaper published during the Bosnian war, reflecting on the development of media freedom over the past 25 years.

While in the 1990s nationalism was the order of the day, today a whole host of challenges – including murky media ownership – face independent journalists across the region. The Balkan Investigative Journalism Network in Serbia, for instance, has documented the campaign against them from authorities and pro-government press on a dedicated website, BIRN Under Fire. Television journalist Jet Xharra and BIRN Kosovo took the government to court over the right to report on the prime minister’s accounts, and to set a legal precedent for press freedom in the state. But Xharra, country director of BIRN in Kosovo, said there is a sense of disbelief among those who had to report during war, that these kinds of battles still need to be fought.

“We cannot understand why, 20 years later, you have to deal with [such] a strain on your reporting,” said Xharra.

During the war years that tore Yugoslavia apart, press freedom, like pretty much every other aspect of society, experienced a profound crisis. Large swathes of the media in the former republics became propaganda tools for ruling elites, even before the fighting started. In fact, concerted media campaigns of hate and fear-mongering played an important part in priming people who had lived side by side for decades for war. As British historian Mark Thompson put it in his 1999 book Forging War, on the media’s role in the conflicts in Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia: “War is the continuation of television news by other means.”

|

Dangers of reporting in the Balkins

Attacks on journalists and journalism in the Balkans, compiled from Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project

SERBIA

Independent online news outlet Peščcanik has been targeted on several occasions after reporting in June 2014 that a senior minister had plagiarised parts of his doctoral dissertation. The site has faced distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and hackers have altered text and blocked IP addresses, thus preventing readers from accessing content.

MONTENEGRO

In May 2015, after reporting on corruption in local government, journalist Milovan Novovic’s car was vandalised. In June, journalist Alma Ljuca’s car was attacked in a similar way. This comes after a car belonging to the daily Vijesti was torched in early 2014.

BOSNIA

In December 2014, police raided the Sarajevo offices of news site Klix.ba, looking for a recording in which the prime minister of the country’s Republika Srpska entity spoke about “buying off” politicians. This came after the site’s director and a journalist were interrogated and asked to reveal their source for the recording, which they refused to do.

CROATIA

In May 2015, journalist and blogger Željko Peratović was attacked by three men outside his home, and hospitalised with head injuries. Peratović is known for his investigative reporting, and has covered the trial of two agents of the former Yugoslav Security Agency.

MACEDONIA

Deputy Prime Minister for Economic Affairs Vladimir Peshevski was filmed physically assaulting Sashe Ivanovski, a journalist and owner of the news site Maktel, who has been critical of the government.

SLOVENIA

In March 2015 photojournalist Jani Bozic received a suspended prison sentence for publishing a photo of Alenka Bratusek, then prime minster elect, which showed him receiving a congratulatory text message from a prominent businessman 20 minutes before results were announced.

KOSOVO

Express journalist Visar Duriqi, who has covered radical Islamists in Kosovo, has received a number of death threats, including threats of beheading.

Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project launched as in 2014 to record threats to media freedom throughout the European Union and EU candidate countries. It has recently expanded to cover Russia and Ukraine. |

Yet during the Balkan wars beginning in the 1990s there were local journalists who, in the face of enormous pressure, rejected nationalist and propagandist lines, and attempted to sift truth from lies and distortion. Beyond the daily struggle that came with just existing in a war zone, independent journalism was dangerous work. As Human Rights Watch points out in a new report on the state of media freedom in the Balkans, journalists who were, at the time, “critical of official government positions were often labelled as traitors or spies working on behalf of foreign interests and against the state”.

Serbia’s B92, a rare dissenting voice in a media landscape shaped by President Slobodan Milosevic’s propaganda strategy, is perhaps the most famous example of independent journalism. Set up in 1989 as a youth-focused radio station (later branching out into TV and web platforms), B92 bravely covered a turbulent time – from the war in Bosnia, to the Nato bombing of Serbia, to the protest movement that eventually saw Milošević ousted. For this, it was continuously hounded by the government. At one point in 1999 authorities commandeered its offices and radio frequency, forcing the station off air, before it could resume broadcasting from a different studio and frequency, under the name B2-92.

In Croatia, President Franjo Tudjman also made sure ultra-nationalism had a place in column inches and on airwaves. Feral Tribune, which started out in 1983 as a satirical supplement in the newspaper Slobodna Dalmacija, had other ideas. Under sustained pressure from the authorities, it covered stories of human rights and conflict that many other outlets avoided, in addition to its biting satire. It was taken to court, publicly burned, and one journalist was even drafted into the army after Feral published an edited photo of Tudjman and Milosevic in bed together on the front page.

Bosnia was the country in the region that would be by far the hardest hit by fighting. But even as war came to Sarajevo, independent journalism survived in some small way. Oslobodjenje, which started out as an anti-Nazi paper in 1943, had a track record of editorial independence. In 1988, staff for the first time voted for their own editor – Kemal Kurspahic – instead of accepting one appointed by the authorities. Just three years later they fought for their freedom again, this time in the constitutional court, as the newly elected nationalist parties agreed to adopt a law whereby they could appoint the editors and managers of Bosnian media. In 1992 came their toughest challenge yet. With the two towers of their office building under fire – in one night they lost six floors on one side and four on the other – they decided to go underground, and continue their work from a nuclear bomb shelter, with no newsprint supplies and no phone links.

“If dozens of foreign journalists could come to report on the siege of Sarajevo and Bosnian war, how could we – whose families, city and country were under attack – stop doing our job?” Kurspahic, now managing editor of Connection Newspapers, told Index. They felt an obligation to their readers: “We could not leave them without news at the worst time of their lives.”

Oslobodjenje even celebrated its 50th anniversary during the war, with 82 papers around the world printing some of their stories. With that they achieved “the ultimate victory”, Kurspahic said, “if the aim of the terror against Oslobodjenje was to silence us as a voice of multiethnic Bosnia”.

“People were getting killed, so we were reporting it. The risk was physical at that time to journalists,” Xharra told Index. Today she hosts Kosovo’s most watched current affairs programme, as well as fulfilling her role at BIRN Kosovo. But she cut her reporting teeth as a translator, fixer and field producer for UK broadcasters – the BBC and Channel 4 – during the Kosovo war. She recalled going through frontlines for a story, and hiding tapes from paramilitary checkpoints, painting a vivid picture of a time when practicing journalism in the western Balkans meant near constant risk of physical harm.

Journalists could be caught in crossfire, or targeted specifically for their work. Kurspahic remembers the Oslobodjenje reporter Kjasif Smajlovic in Zvornik, who sent his wife and children away, and stayed to report on the fall of the town until he was killed by Serbian paramilitary forces in April 1992. In 1999, Slavko Curuvija, known for his critical reporting, was shot 17 times in a Belgrade side street, just days after a pro-government daily had labelled him a Nato supporter. In many cases, there has been little to no accountability for such crimes, breeding a culture of impunity that still hangs over the region.

Because while the darkest days for press freedom in the Balkans came during wartime, peace has not brought the improved conditions many hoped for. At a talk in March, Dunja Mijatovic, the OSCE’s free expression representative, went as far as to say that the situation now is worse than in the aftermath of the conflicts.

And today the media itself remains part of the problem, especially when journalists turn on their colleagues. One prominent example is the story of BIRN Serbia. Following their critical investigation into a state-owned power company, Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic labelled the group liars who had been funded by the EU to speak against his government. That attack was then taken forward by the pro-government Serbian press, including in the newspaper Informer. Just one example where the media has been a less than staunch defender of its own rights.

Data from Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project, which tracks media freedom across Europe, indicates that worries of threats to media rights are justified. In just over a year it has received more than 170 reports of violations from the countries of the former Yugoslavia. Incidents included a Croatian journalist who received a letter saying she would “end up like Curuvija”; a Bosnian journalist threatened over Facebook by a local politician; Kosovan journalists depicted as animals on several billboards; a Montenegrin daily that had a company car torched; a Macedonian editor who had a funeral wreath sent to his home; and a Slovenian who faced charges for reporting on the intelligence agency. Online and offline, physical and verbal, serious threats to press freedom remain, some 20 years on.

© Milana Knezevic

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.

23 Sep 2015 | Africa, Angola, mobile, News and features

Four of the jailed Angolan activists in the case that has dragged on since June. Photograph: Ekuva Estrela

Over the past month, the Angolan government has continued its crackdown on freedom of expression and the right to assemble in the country.

Most recently, on 14 September, human rights activist José Marcos Mavungo received a six year jail sentence for attempting to hold a peaceful protest on 14 March. Even though the demonstration was banned, a judge of the provincial court of Cabinda charging him with rebellion.

Mavungo is a former member of “Mpalabanda”, a group that was banned after it highlighted rights abuses by security forces in the province.

Concerns have been raised that the activist’s sentencing represents a serious abuse of the Angolan justice system. “It did not meet basic due process guarantees and formal trial standards required by Angolan law,” wrote 2015 Index journalism award winner Rafael Marques de Morais, Angolan activist and founder of anti-corruption website, Maka Angola. “The judge, Jeremias Sofrera, ignored the blatant lack of evidence exposed during the trial and all allegations and complaints presented by the defense lawyers.”

Mavungo’s legal counsel said they will appeal his sentencing.

Marques has repeatedly been targeted by Angolan authorities for his investigative journalism. He was briefly detained and had his passport confiscated by immigration officers on 10 September while returning from a trip to South Africa. Marques wrote that he was given contradicting explanations as to why he was being held. It was unclear whether a new order had been issued or an old one banning him from leaving Angola was still in force. Ultimately his passport was returned and he was released.

The incident did not deter the Marques, who only a few days later helped to organise a meeting in solidarity with political prisoners, which was attended by more than a thousand people. The event was broadcast live by the radio station and streamed through various social networks for nearly four hours.

The mother of 19-year old political prisoner Nito Alves, Adalia Chivonde, told the gathering that her son was being subjected to psychological torture and isolation. “We are asking the President and General Ze Maria [Chief of the Military Intelligence and Security] to free our sons,” she said.

One of the most well-known recent cases is that of 15 men imprisoned since June on charges of civil disobedience and planning to overthrow the government. The men, who were part of a study group, had been organising peaceful demonstrations against President José Eduardo dos Santos since March 2011. On 28 August, the families of the prisoners staged a march in support their loved ones despite a banning order issued by the local governor.

The families have repeatedly attempted to hold public demonstrations to bring attention to their relatives’ situation, but have been thwarted by bureaucratic obstacles. The family members have responded by submitting petitions and modifying their plans to meet the official objections.

The protest was supposed to take place at 3pm on Friday 28 August at Praca da Independencia (Independence Square) in Luanda. However, as the protest coincided with the 73rd birthday celebrations of President dos Santos, the streets were not only filled with music, dancing and craft fairs, but also secret police agents and the presidential guard, with RPG-7s and AK47s in tow.

“We are not going to sit and wait for our sons. We really are going to march. It is our right,” stated Adália Chivonde, the mother of prisoner Manuel Nito Alves, in the days running up to the demonstration.

“We will not be able to hold the demonstration because, as you can see, [they] have already invaded all the space,” said Elsa Caolo, sister of Osvaldo Caolo, one of the jailed men. “We can not even walk in peace — we are to be chased down the street […] we can’t speak out.”

22 Sep 2015 | Austria, mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

Panelists at the OSCE meet on online attacks against journalists: writer Arzu Geybulla; Gavin Rees, Europe director of the Dart Center for journalism and trauma; Becky Gardiner, from Goldsmiths, University of London; journalist Caroline Criado Perez

“This is not something that only ‘ladies’ can fix,” emphasised Dunja Mijatovic, the OSCE’s Representative on Freedom of the Media at an expert meeting on the safety of female journalists in Vienna on 17 September 2015, which Index on Censorship attended.

The importance of collectively tackling the growing problem became an overarching theme of the conference. “There is a new and alarming trend for women journalists and bloggers to be singled out for online harassment,” said Mijatovic, while highlighting the importance of media, state and NGO voices coming together to address the abuse.

Arzu Geybulla and Caroline Criado Perez, journalists from Azerbaijan and the UK respectively, started the meeting with moving testaments of their own experiences. Despite covering very different topics, they have received shockingly similar threats – sexual, violent and personal. “Shut your mouth or I’ll shut it for you and choke you with my dick” was one of the messages received by Perez after she campaigned for a woman to feature on British banknotes.

Although male journalists also receive abuse, women experience a two-fold attack, including the gendered threats. Think tank Demos has estimated that female journalists experience roughly three times as many abusive comments as their male counterparts on Twitter.

The problem, said Perez, was not just the threats but how the women who receive them are then treated. “Women are accused of being mad or attention seeking, which are all ways of delegitimising women’s speech,” she said. “People told me to stop, close my Twitter account, go offline. But why is the solution to shut up?” She added: “This is a societal problem, not an internet problem.”

“Labelling a person, and making that person an object, is particularly common in Azerbaijan,” said Geybulla, an Azeri journalist and Index on Censorship magazine contributor who was labelled a traitor and viciously targeted online after writing for a Turkish-Armenian newspaper. “Our society is not ready to speak out. You can’t go to the police. The police think it must be your fault.”

The intention of the meeting was to highlight the problem, while also proposing courses of actions. Suggestions included calls for more education in digital literacy; more training for police; more support from editors and media organisations, and from male colleagues. There was some disagreement on whether the laws were robust enough as they stand, or needed an update for the internet age.

Becky Gardiner, formerly editor of Guardian’s Comment is Free section, spoke about how her own views on dealing with online abuse had changed, having initially told writers they should develop a thicker skin. “It is not enough to tell people to get tough. Disarming the comments is not a solution either. That genie is out of the bottle.” Gardiner, who is now a lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London, is working on research into the issue, as commissioned by the Guardian’s new editor, Kath Viner.

It was suggested that small but crucial steps could be taken by media organisations to avoid inflammatory and misleading headlines (which are not written by the journalist, but put them in the firing line) and to be careful of exposing inexperienced writers without preparation or support. Sarah Jeong from Vice’s Motherboard plaform said, in her experience, freelancers often came the most under attack because they don’t have institutional backing.

The OSCE said this will be the first in a series of meetings, with the aim of getting more organisations to take it serious and to produce more concrete courses of action.

Read more about the online abuse of women in the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, with a personal account by Gamergate target Brianna Wu and a legal overview by Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (Fire).

Tweets from OSCE’s #FemJournoSafe conference:

https://twitter.com/julieposetti/status/644456066432937984