6 Jul 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

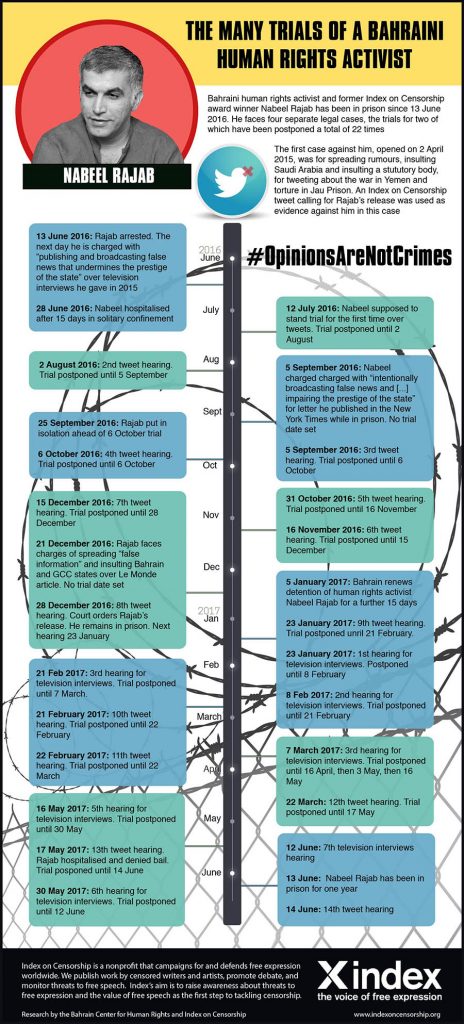

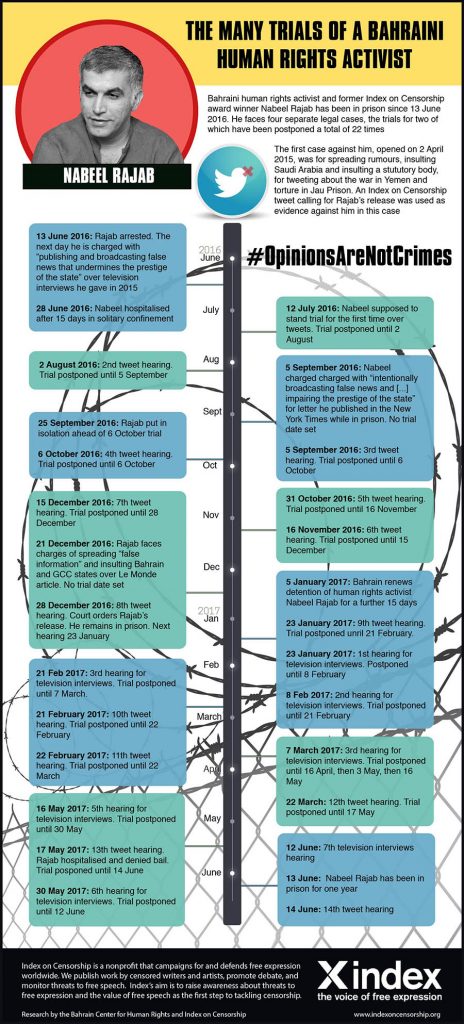

The trial of Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab has been delayed yet again. He was due to stand trial on Sunday 2 July, but this was postponed until 3 July and again until 10 July.

Rajab, president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights and Index award winner, was arrested on 13 June 2016 and remains in prison despite a court order to release him on 28 December 2016. He faces four separate legal cases, the trials for two of which have been postponed over 20 times.

“We are particularly concerned about Rajab’s health, which continues to deteriorate due to the poor conditions and mistreatment he receives in prison,” said Melody Patry, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship. On 5 April 2017, Rajab underwent major surgery at a military hospital to remove ulcerated tissue from his lower back. He was returned to his cell at East Riffa Police Station two days later against medical recommendations.

“My father’s fate is unknown. He might end up in a prison cell for the next 18 years, so it’s difficult and tiring for him and for our family,” Rajab’s son Adam Rajab told Index today. “However, that does not mean he will ever stop his struggle for rights and freedom.”

“We all know that my father will be released if he guarantees them that he will be silent, but he will not,” Adam added. “He will always be a voice for the victims of human rights abuses and he will always stand against oppressors and dictators. As he always says ‘I am willing to pay the price for freedom and democracy.'”

Index continues to express concern over the treatment of many human rights defenders in Bahrain including women’s rights activist Ebtisam Al-Sayegh, who this week was arrested following a raid on her home and now risks being tortured. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”6″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1499332927690-0ca55f53-22f9-3″ taxonomies=”3368″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”6″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1499332927690-0ca55f53-22f9-3″ taxonomies=”3368″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Jul 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

As she was getting ready for bed on 3 July, Bahraini women’s rights defender Ebtisam Al-Sayegh was arrested by masked officers. Her whereabouts remain unknown.

Just before midnight, five civilian cars and one minibus arrived at Al-Sayegh’s home. Two female officers demanded she handed over both her mobile phone and her national identity card. No arrest warrant was presented and the officers did not answer questions from her family on why she was being arrested. Her family believe these officers are from the Bahraini National Security Agency.

“Index calls for the immediate release of Ebtisam Al-Sayegh. The conditions of her arrest are deeply concerning and we fear she is again at risk of torture,” said Melody Patry, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship. “The unceasing harassment and persecution of human rights defenders in Bahrain are blatant violations of human rights and in total contraction with claims of progress or improvement in this regard.”

Al-Sayegh, a human rights defender with Salam for Democracy and Human Rights, was detained and tortured in late May 2017 for documenting the abuses in Duraz where five protesters were killed and about 300 arrested.

During this time, Al-Sayegh was blindfolded and sexually assaulted while standing for seven hours of interrogation. Al-Sayegh told Amnesty: “The men told me ‘no one can protect you’. They took away my humanity, I was weak prey to them.”

Al-Sayegh was also detained in March after she participated in the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. In June, the UN released a statement about the increasingly hostile situation in Bahrain. UN experts said: “We are particularly worried about these measures, coupled with the campaign of harassment aimed at human rights defenders, who are increasingly being charged with offences for which the death penalty may be imposed.”

4 Jul 2017 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Spain

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Within the last month, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform has recorded a number of restrictions on media access to events in Spain by police and politicians.

Melody Patry, Index’s head of advocacy, called to attention these encroachments on press freedoms by Spanish law enforcement: “The police are clearly — intentionally or not — restricting access to information and interfering with legitimate journalistic work,” she said. “This further highlights the need for improved policy and training of law enforcement bodies to protect freedom of expression and ensure journalists’ safety.”

On 10 June, police officers blocked access to journalists covering an eviction in Santiago de Compostela and threatened to fine them.

During a protest against an eviction, police obliged reporters to stand behind the police cordon a hundred meters from where the eviction was taking place. This restricted access made it difficult for the journalists to see and report on the event.

Police agents in plain clothes asked reporters for their IDs and personal documents while simultaneously refusing to identify themselves. According to the journalists, the police acted aggressively, wielding batons against them, threatening them with fines for taking photos and warning reporters that photos already taken would be erased.

Journalist Cristina Fallarás received a €600 fine on 13 June for disobeying police orders and standing on the street during a Madrid protest.

On 18 May, Fallarás participated in a protest against the assassination of Mexican journalists in front of the Mexican embassy in Madrid. Police cordoned off a road near the embassy. “There were so many people at the protest, we were squeezed, so I went on the road. A policeman told me to go back to the pavement,” the journalist told Público. Fallarás then explained to the policeman that she had not interrupted traffic on the road and that there were many people on the pavement. He asked for her ID.

“When I gave my ID I knew they were going to fine me but I didn’t think it would be a €600 fine,” Fallarás said. She was fined according to the Citizen Security Law, which some critical media outlets have called a ‘gag law’. She was notified of the fine on 13 June and has indicated a plan to appeal it.

On 16 June, the Spanish newspaper El País removed an article it had published on the parliament spokesman of the ruling party because the editor-in-chief considered it to be “inappropriate”.

The article criticised the behaviour of MP Rafael Hernando during a debate with MP Irene Montero. Within the opinion article, author Salazar called Hernando a “male chauvinist and misogynist”.

“They (El País) told me that the article is fantastic, that it will be published on the cover page of the web edition,” Salazar told Público. A few hours later, after 300 comments appeared on the article, El País told Salazar that the editor-in-chief, Antonio Caño, had read the article and said that it would have to be either “softer” or removed. “I told them that there was nothing to change,” said Salazar. He received another phone call, this time from the director of El País, who told him that to call Hernando a “male chauvinist and misogynist” was not appropriate. The article was then removed from the website.

The left-wing Podemos party failed to invite six Spanish media outlets to an “off the record” breakfast briefing on 20 June where they introduced the new party spokespeople to the rest of media.

Podemos excluded reporters from El País, la Cadena SER, El Periódico de Catalunya and online outlets El Independiente, Voz Pópuli and Ok Diario. The Madrid Press Association called it a “veto” on the media and asked Podemos to refrain from such actions in the future. According to the APM, all affected journalists typically report on Podemos.

Podemos’ members say that the party has a right to decide who will be invited to their private events and that there was a lack of confidence with the reporters in question.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Jul 2017 | Europe and Central Asia, Magazine, News and features, Russia, Volume 46.02 Summer 2017 Extras

The summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the 1917 Russian Revolution still affects freedom today, in Russia and throughout the world.

To mark the release of the issue, Index has compiled a reading list for people wishing to learn more about its legacy in the world today. This list includes works from Soviet Russia and post-Soviet Russia, including Russia under Putin today.

Soviet Russia

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, God keep me from going mad*

1972; vol 1, 2: pp.149-151

An excerpt of a longer poem written by Solzhenitsyn while in a labour camp in North Kazakhstan. The camp later became the inspiration for Solzhenitsyn’s novel A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Alexander Glezer, Soviet “unofficial” art*

1975; vol 4, 4: pp. 35-40

Glezer was responsible for organising the now famous unofficial art exhibitions in Moscow in 1974. The first exhibition, on 15 September, was ‘”bulldozed” by police and KGB agents, and a number of artists who tried to exhibit their work were arrested. Two weeks later, however, an open-air exhibition did take place, after the authorities gave permission, and some 10,000 people turned up to see paintings and sculptures by modern Soviet artists who did not enjoy official favour.

Michael Glenny, Orwell’s 1984 through Soviet eyes*

1984; vol 13, 4: pp. 15-17

This article examines Soviet interpretations of 1984, including the assertion that George Orwell was actually critiquing capitalism, not the USSR, with his novel.

Natalya Rubinstein, A people’s artist: Vladimir Vysotsky

1986; vol 15, 7: pp. 20-23

This is an article about the musician Vladimir Vysotsky, once called “the most idolised figure in the Soviet Union”. His songs were circulated on homemade tapes, though never officially recorded until after his death.

Irena Maryniak, The sad and unheroic story of the Soviet soldier’s life

1989; vol 18, 10: pp. 10-13

An Estonian reporter’s exposé prompts a call from the army. Madis Jurgen, who brought to light the dark side of the Soviet armed forces, left Tallinn on Friday 13 October, bound for New York and Toronto, from where he decided to await events.

Post-Soviet Russia

Svetlana Aleksiyevich, A Prayer for Chernobyl

1998; vol 27, 1: pp. 120-128

Early on 26 April 1986, a series of explosions destroyed the nuclear reactor and building of the fourth power generator unit of Chernobyl atomic power station. These extracts are not about the Chernobyl disaster but about a world of Chernobyl of which we know almost nothing. They are the unwritten history.

Viktor Shenderovich, Tales from Hoffman*

2008; vol 37, 1: pp. 49-57

As they say, still waters run deep. On 8 February 2000, an announcement was made in the St Petersburg Gazette by members of the St Petersburg State University Initiative Group. Shortly beforehand they had, in competition with others, nominated Putin as a presidential candidate and now wished to demonstrate their enthusiasm for their former pupil. What they published was a denunciation.

Fatima Tlisova, Nothing personal

2008; vol 37, 1: pp. 36-46

Fatima Tlisova was brutally beaten for her uncompromising journalism on the North Caucasus. Here, she recounts the tactics used to intimidate her.

Anna Politkovskaya, The cadet affair: the disappeared

2010; vol. 39, 4: pp. 209-210.

An article on the disappeared in Chechnya, who officially number about 1,000, but unofficially are almost 2,000. They disappeared throughout the war. The author, Anna Politkovskaya, was murdered in her Moscow apartment in a contract killing in 2006.

Nick Sturdee, Russia’s Robin Hood*

2011; vol 40, 3: pp. 89-102

Widespread frustration with the establishment has fostered a brand of political street art that is taking the country by storm.

Ali Kamalov, Murder in Dagestan

2012; vol 41, 2: 31-37

Ali Kamalov, the head of Dagestan’s journalists’ union fears for the future of press freedom following the murder of the country’s most prominent editor. On 15 December 2011, Hadjimurad Kamalov was murdered in Makhachkala, the seaboard capital of Dagestan.

Maxim Efimov, Religion and power in Russia

2012; vol 41, 4

Although the Russian constitution enshrines freedom of expression, the authorities routinely clamp down on anybody who treasures this fundamental right. State officials, judges, deputies, prosecutors and police officers serve the ruling regime and control society, rather than defend the constitution or protect human rights.

Elena Vlasenko, From perestroika to persecution

2013; vol 42, 2: pp. 74-76

Elena Vlasenko covers wavering hopes for an open Russia, and the evolution of repressive legislation, state censorship and journalists under threat.

Helen Womack, Making waves

2014; vol 43, 3: pp. 39-41

Helen Womack interviews the founder of the last free radio station in Putin’s Russia. These men are not dissidents, just journalists dedicated to professional principles of objectivity and balance. But in Putin’s Russia, where almost all the media spout state propaganda, that position looks like radical nonconformity, and it seems a wonder that Echo survives.

Andrei Aliaksandrau, Brave new war*

2014; vol 43, 4: 56-60

In the winter 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Andrei Aliaksandrau investigates the new information war between Russia and Ukraine as he travels across the latter country.

Andrei Aliaksandrau, We lost journalism in Russia

2015; vol 44, 3: pp. 32-35

Andrei Aliaksandrau examines the evolution of censorship in Russia, from Soviet institutions to today’s blend of influence and pressure, including the assassination of journalists.

Andrey Arkhangelsky, Murder in Moscow: Anna’s legacy*

2016; vol. 45, 3: pp. 69-74.

Andrey Arkhangelsky explores Russian journalism a decade on from Anna Politkovskaya’s murder and argues that the press still struggles to offer readers the full picture.

*Articles which are free to read on Sage. All other articles are available via Sage in most university libraries. To find out more about subscribing to the magazine in print or digitally, click here.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”6″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1499332927690-0ca55f53-22f9-3″ taxonomies=”3368″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”6″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1499332927690-0ca55f53-22f9-3″ taxonomies=”3368″][/vc_column][/vc_row]