1 Mar 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship welcomes the announcement by Secretary of State Matthew Hancock that the government will not implement Section 40 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013.

Implementing Section 40 would have meant that Index, which refuses to sign up to a state-backed regulator – and many other small publishers – could have faced crippling court costs in any dispute, whether they won or lost a case. This would have threatened investigative journalists publishing important public interest stories as well as those who challenge the powerful or the wealthy.

We have argued consistently that Section 40 is a direct threat to press freedom in the UK and must be scrapped. This part of the act, created as a response to the Leveson Inquiry into phone hacking, has been on the statute for several years but was not enacted because — until 2016 — there was no approved regulator of which publishers could be part. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1519906042363-4bc2dd22-cabf-7″ taxonomies=”6534″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

1 Mar 2018 | China, News and features

With the historic announcement at the weekend that China would end the two-term limit on presidents, meaning the current leader Xi Jinping could be president for life, it created an online storm.

People took to the popular Chinese social media apps Weibo and WeChat to express either disdain and outrage. It didn’t take too long for the country’s well-oiled censorship apparatus to swing into action and ban all of the obvious terms related. Within hours, you couldn’t say “I don’t agree”, “migration”, “emigration”, “re-election”, “election term”, “constitution amendment”, “constitution rules”, “proclaiming oneself an emperor”, “Yuan Shikai (Former Emperor)” and “Winnie the Pooh” (more on this soon).

At the same time, Chinese citizens created and widely shared a series of memes. Most of these have since been removed, but not before enough people saw them, screenshots were taken and they were spread on media beyond the censor’s reach. Here’s an overview of some of the best:

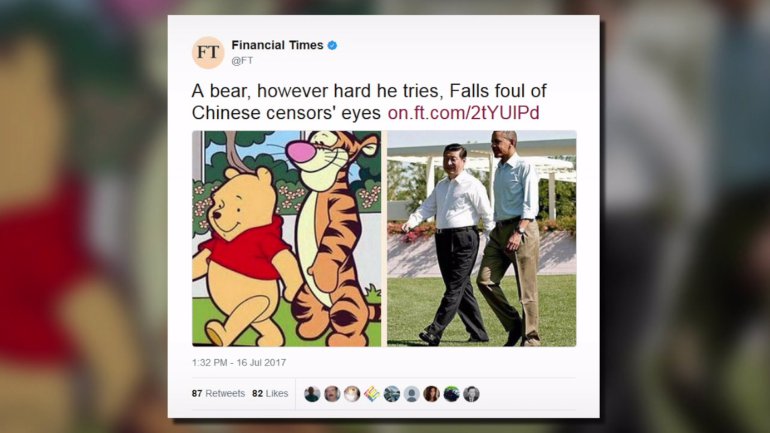

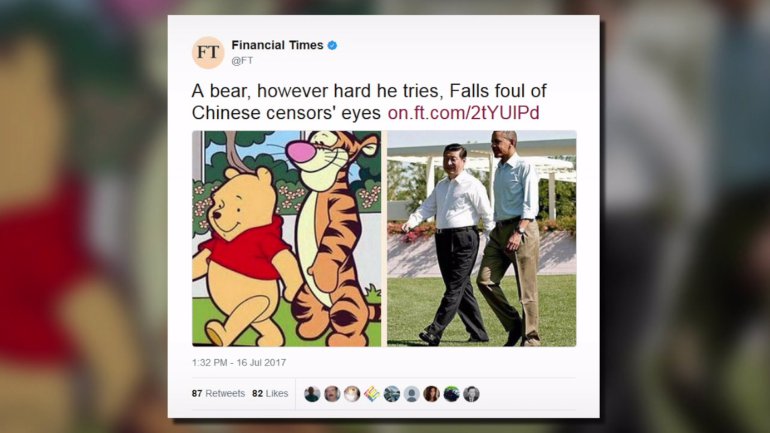

King Winnie

The world’s favourite cuddly teddy bear, unless you’re a Chinese leader. After a meme likened the cartoon character with the Communist Party leader went viral in 2013, Winnie the Pooh became a popular meme when riffing Xi – and arguably the world’s most censored children’s book character. That has not stopped people persisting with the animated representation of the leader. In response to the new proposal, several of the following memes circulated:

The original meme that prompted the government to ban Pooh in 2013.

Another oldie but goodie expressing Xi’s disdain for Pooh, created by cartoonist Badiucao in the China Digital Times.

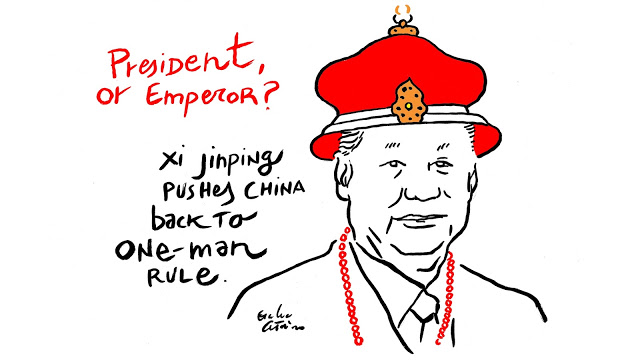

Emperor Xi

An obvious one here. Graphics emerged with references to past emperors of China, emphasizing the point that this new proposal is reminiscent of past Chinese rulers and dictators. Some of these graphics censored include:

Cartoon created on political activism website, ChannelDraw.

Graphic created after the announcement by Badiucao, prolific political activist and cartoonist.

Silver lining?

Perhaps the best of the memes, combining as it does a joke about Xi’s term extension and a joke about the common Chinese pressure to get married. It reads: “My mom said that I have to get married before Xi Dada’s term in office ends. Now I can breathe a long sigh of relief.”

Don’t forget the bunnies

While the latest news is sure to keep the censors busy for some time, they’ve been waging another war in China this year against #Metoo, which has recently come to the country and has not been well-received by a government uncomfortable with any form of protest (read our article on protest in China here). Initially the hashtag #woyeshi went viral, which literally means “me too”. When that was banned, people got creative. Introducing the rice bunny. Rice in Mandarin is mi and bunny tu, pronounced basically “me too”. Now China’s internet is awash with images of bunny and rice combos, that is until the censors catch up. Bunnies and Pooh bears – China’s internet might be censored, but it’s never boring.

The Rice Bunny is against sexual harassment. Image from @七隻小怪獸 on Weibo

28 Feb 2018 | Index in the Press

The default position of politicians and prominent public figures under fire is to blame a free press. On the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht the Index on Censorship, which monitors attacks on world media, reiterates that freedom of expression is a freedom that benefits all. Recently, it noted that once you accept the principle that only certain voices can be heard, “it can be applied to your voice just as easily”. Read the full article

28 Feb 2018 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Recent developments in Turkey, once seen as a role model for the Muslim world, have shown that concepts such as the rule of law and right to free speech are no longer welcome by the Erdogan government.

With 156 journalists behind bars as of 26 February 2018 and the closing down of more than 150 media outlets by virtue of the state’s of emergency decrees, Turkey is the global leader in suppressing the media. The irony is that Erdogan was once a victim of an earlier oppressive regime in the late 1990s, having been dismissed as mayor of Istanbul, banned from political office and put in prison for three months for inciting religious hatred after he recited part of a poem by the Turkish nationalist Ziya Gokalp at a political rally.

The destruction of the rule of law in Turkey has been in the making since the anti-government Gezi Park protests and corruption probes of 2013. However, the government has made its intentions on the right to free speech crystal clear in the aftermath of the 15 July 2016 coup attempt. Many journalists and writers have been imprisoned over accusations as absurd as spreading subliminal messages to promote the coup.

Some of them — like Die Welt journalist Deniz Yucel — have languished in detention without charge for a year. Yucel was used as a bargaining chip against Germany and was only freed after chancellor Angela Merkel put pressure on the Turkish government. Immediately after he was let out of detention he published a video message in which he said: “I still don’t know why I was arrested and why I have been released.”

Ahmet Sik, another well-known journalist, was imprisoned because of his thorough investigations into the dark sides of the coup attempt. Can Dundar was arrested for publishing about Turkish intelligence’s illegal arms transfers to Syria. He was kept in prison for several months and eventually released on a constitutional court decision in February 2016. He fled the country and currently lives in Germany. Veteran journalists Sahin Alpay and Mehmet Altan, on the other hand, were not so lucky. They had been granted freedom by the constitutional court but a local court refused to implement their release. Recently, the Altan brothers, Mehmet and Ahmed, and another senior journalist, Nazli Ilicak, have been brutally sentenced to aggravated life prison sentences. Examples of the obscene unlawful imprisonment of journalists can go on and on.

The heart of the issue is that Turkish journalists do excellent work. They go to extraordinary efforts to make sure the public is informed about corruption, illegal arms transfers, extrajudicial killings of Kurds and minorities, shady affairs of the ruling party with the judiciary and unanswered questions about the coup attempt. The government doesn’t want to see these issues make headlines, and for defying it many journalists have sacrificed their freedom.

Behind the thin veneer of Turley’s judicial system is the political machine manufacturing countless crimes. After 500 days pretrial detention, Ahmet Turan Alkan, an intellectual and a respected writer, pointed that out by telling a judge: “Your honour, I know you can’t release me because if you decide to do so you will be jailed.”

Turkey’s journalists are faced with a unique problem: if they continue to lay bare the truth for all to see they risk exile or prison. In a normal country, journalists performing at the height of their abilities would be encouraged or rewarded, perhaps not by their governments but by the society as a whole. But not so in Turkey, where the government mouthpieces and politically-aligned media outlets spout the latest propaganda to manipulate Turks. Unfortunately, the majority of people actually believe that most of the arrested journalists are criminals or terror supporters.

This collective hostility to freedom of expression makes Turkey one of the biggest violators of press freedom in the 42 European-area countries Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project monitors; one of the lowest ranking countries in Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index; and deemed “not free” by Freedom House’s evaluation.

It’s not just journalists. Academics, rights defenders, philanthropists and lawyers also face punishment for carrying out their professional responsibilities on behalf of the public. Disclosing the unlawful practices of those in power is all it takes for an individual to find themselves on the wrong side of the bars. As with Alpay and Altan, a court had ordered Taner Kilic, the chairman of Amnesty Turkey, to be released from detention, but the prosecutor put him back in prison. Kilic and his colleagues are being targeted in retribution for Amnesty International’s work to make the world aware of the inhumane conditions in Turkey’s post-coup attempt era.

The government’s intolerance toward dissenting voices can also be seen in its treatment of university professors, students and others who signed an Academics for Peace petition, which called for an end to violence in the Kurdish region of the country. Hundreds of distinguished academics have found themselves summoned to courtrooms. For taking a stand about the ongoing tragedy in Kurdish cities, the majority of these academics are dehumanised and defamed. They have not only become enemies of the state but enemies of all Turks.

Yes, the government has terrorised ordinary people with the narrative of the “world against great Turkey” and urged them to stand against outspoken figures who are the “spies, traitors and enemies”.

What do the EU and other international organisations do? Mostly expressing their “concern” in different formats such as “great”, “deep” or “serious”. Even the European Court of the Human Rights has not issued a single verdict against Turkey’s post-coup purge which has seen the country become the world’s largest jailer of journalists.

On the same day the Altan brothers were sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in prison, Tjorbon Jaglan, the secretary general of the Council of Europe was on a two-day visit in Turkey. He didn’t utter a single word about their situation. What else could better fit the definition of the “banality of evil” conceptualised by Hannah Arendt?[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1519832159496-f7b69135-ce98-10″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]