21 Apr 2021 | Belarus, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116608″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Today Index’s friend and former colleague, Andrei Aliaksandrau, will spend his 100th day in detention in Belarus. As we renew our calls for his immediate and unconditional release, we are joined by Christine Jardine MP who will become his honorary godparent as an expression of her solidarity with him.

“The conditions in which opposition activists like Andrei are being kept are not acceptable. Our Government must work with our European partners to put pressure on the Belarusian Government to release those held on political charges,” Jardine said. Jardine is joining more than 160 politicians from across Europe as they stand in solidarity with political prisoners in Belarus through the #WeStandBYyou campaign.

Belarusian authorities accuse Aliaksandrau of financing the protests that have rocked Belarus since President Alexander Lukashenko returned to power after the fraudulent elections last August. According to the authorities, Aliaksandrau paid the fines of hundreds of protesters who were detained between August and November 2020, using funds sent to him by the London-based BY help fund. By mid-November, Belarus had ordered banks to freeze any money sent from the fund.

“Andrei is a fearless human rights defender, and he should not have to spend one day – much less 100 days – in prison,” Jessica Ní Mhainín, Index’s policy and campaigns manager said. “Andrei is one of 357 political prisoners currently being detained in Belarus. They need us – whether we are members of parliament like Christine Jardine or ordinary citizens – to use our voices in defence of their right to use theirs.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”172″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Apr 2021 | News and features

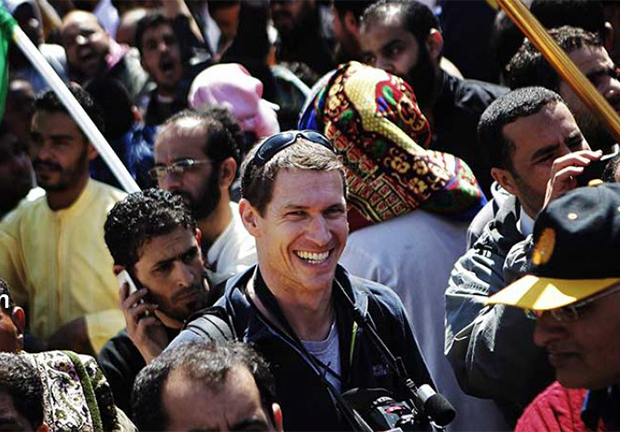

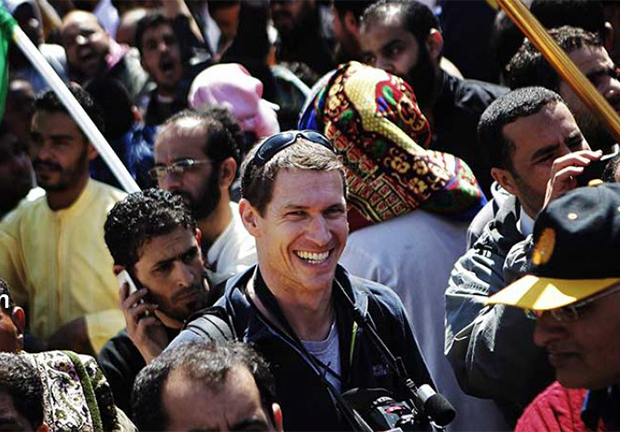

Tim Hetherington’s mission to create a better understanding of the world cast him in many roles: photojournalist, filmmaker, human rights advocate, artist and a leading thinker in media innovation. He was killed in Libya by a mortar in in April 2011.

On 20 April 2011, photojournalist Tim Hetherington was killed by shrapnel from a mortar blast in Misrata, Libya.

Born in Liverpool on 5 December 1970, Hetherington was a prominent photojournalist whose work was acclaimed by his peers. He was once described as one of ‘brightest photojournalists of his generation’ and his work included co-producing the Oscar-nominated Restrepo, a 2010 documentary film about US soldiers in the war in Afghanistan.

His passion for his work was rooted in developing a relationship between his audience and the events portrayed in his work. He once said: “I want to record world events, big history told in the form of a small history, the personal perspective that gives my life meaning and significance. My work is all about building bridges between myself and the audience.”

A clear passion for people is what led him to the Libyan civil war and to the front line between rebel forces and those of Muammar Gaddafi, where he met his death.

After a degree in photojournalism from Cardiff University in 1997, Hetherington pursued his photography career. His coverage was extensive and ranged from the aftermath of the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, to the events during and after the Liberian civil war.

Director of the Tim Hetherington Trust, Stephen Mayes, shed a light on where his appetite for his work came from. He wrote: “His family talks about a child who was playful yet intense, perpetually curious and seeking new experiences, pushing the proper boundaries of an English adolescence, characteristics that later served him well as a journalist.”

“It was never enough to simply witness events, he had to experience the lives of his subjects”

After Hetherington’s death, Sebastian Jungar, the director of Restrepo and someone who worked closely with him released the film “Where is the Front Line from Here? The Life and Time of Tim Hetherington”, a documentary about his life and work.

Junger told Index of his work with Hetherington and his unique way of thinking.

“In my mind he was some ways a brother. We were in combat together and it builds a kind of experience of brotherhood that is hard to find anywhere else,” Junger recollected.

“When he was killed, I was devastated like I had never been devastated by anything. Among other things, I decided to stop combat reporting.”

“He really thought out of the box. He said to me ‘I only use a camera because that is the easiest way to tell a certain kind of story. If I could tell that story without a camera I would drop it in a second’.”

During the filming of the pair’s co-project, Restrepo, Junger recalls a moment that typified Hetherington’s approach to his work.

“There was a lot of combat, but when there wasn’t, the guys [US infantry] would basically sleep as much as they could.”

“One day everyone was asleep, but Tim was sort of creeping around and I asked him ‘What are you doing? It is like 100 degrees and everyone is asleep’.”

“He said ‘Don’t you get it? They look like children. This is how their mothers see them’.”

Tim Hetherington’s name lives on not only through his work but also through an eponymous fellowship with Index on Censorship, established in 2016 in conjunction with Liverpool John Moores University and the Tim Hetherington Trust. The fellowship sees a student from the university join Index for a year as editorial assistant on the magazine and website, gaining valuable journalistic experience.

Steve Harrison, journalism lecturer at LJMU’s Liverpool Screen School, who manages the fellowship, spoke of the how Hetherington’s work continues to be a good example to his students.

“His main media output was documentaries, so it is of particular interest to people looking to go into that. But it was his journalism roots that is relevant to all students and an example of a way in which journalism can be put to a very powerful use,” he said.

“It is not just journalism, it is art as well, the intersection of journalism and art. It is our view that Tim’s work was an inspiration for current and future journalists and one of the main reasons we thought naming [the fellowship] after him was so appropriate. An ideal fit.”

The fellowship has helped a number of former LJMU students gain a foothold in the industry. Last year’s recipient Orna Herr, now a communications officer for the British Science Association, said: “The Tim Hetherington fellowship gave me incomparable experience of working in journalism and the confidence to pitch and write my own stories. Being a member of the team at Index allowed me to be part of the process of editing and publishing articles from all over the world, working closely with the journalists themselves and the editorial team.

“I left Index with a portfolio of work I’m very proud of.”

Lewis Jennings, the 2018/19 fellow, said, “I learned a lot about the craft of journalism and also what it means to be an advocate for free expression. It opened my eyes to a lot of things that go on in the world in terms of threats to the media and free speech. It has enabled me to pursue a career in journalism, both in print and radio. It was an honour to carry on the legacy of Tim Hetherington through the fellowship. Tim’s work as a visual storyteller and human rights advocate continues to inspire ten years after his death.”

20 Apr 2021 | Croatia, Monaco, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116596″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]A British oil industry whistleblower was detained last night by armed police in Zagreb and held overnight against his will in a psychiatric hospital after British diplomats raised concerns about his mental health.

Jonathan Taylor has been stranded in Croatia since July last year, when he was arrested while entering the country for a holiday with his family. The authorities in Monaco, where he worked for oil company SBM Offshore, have accused him of extortion and requested his extradition to the Principality. He is awaiting a decision from the Croatian Supreme Court this week.

In 2013, Taylor blew the whistle on a multimillion dollar network of bribery payments made by SBM around the world and cooperated with prosecutors in the UK, the US, Brazil and the Netherlands. These investigations resulted in fines against the company to the tune of $827 million and the conviction of two former CEOs of SBM for fraud-related offences. However, Monaco has decided to target the whistleblower rather than those responsible for the bribes.

Freedom of expression organisations, including Index on Censorship, have been lobbying the British government to put pressure on Monaco and Croatia to allow Taylor to return England where his family is now based. Media Freedom Rapid Response partners have demanded an end the extradition proceedings.

Taylor had alerted the British Embassy and the Sofia-based regional consul last Friday about his deteriorating mental health and was asked to put his thoughts into writing. This set off a train of events in Zagreb that Jonathan Taylor relates in his own words here:

“I was met by two armed officers at the roadside to the entrance of the forecourt to my apartment at about 9:15pm last night. I was told I had to wait with them until a psychiatrist arrived in an ambulance. After about 45 minutes we went up to my apartment as it had started raining and the ambulance still hadn’t arrived.

“At about 10:15pm the ambulance drivers arrived and joined the two policemen in my apartment. I was then told I had to accompany them to hospital. I protested stating I had been told a psychiatrist would come to me. I made it clear I was not prepared to leave the apartment. Then four more other armed officers arrived. I again explained I was not happy to go to hospital (see picture top).

“Eventually two of the armed officers manhandled me to the ground causing my head to hit a wall and a resulting headache. I was the cuffed with face against the floor and manhandled out of my apartment into an ambulance where I was strapped into a stretcher. Upon arrival at hospital (no idea where I am) I was dragged out of ambulance and sat on a chair just inside the door to the hospital. I was left there under guard, still handcuffed, for about 30 minutes.

“A lady came to see me (apparently a psychiatrist, but she did not introduce herself) and she asked a few basic questions like ‘why did I arrive with the police?’ and ‘how long had they been following me?’ (!).

“Shortly after this I was taken to a room, still cuffed, where I was strapped to a bed by my feet and legs and my hands. I then refused unidentified tablets and was invited to swallow them whilst someone held a cup of water to my mouth. I refused. I was then forcibly turned and something was injected into my upper thigh. It was now at least 12:30am. At about 6:30am, again against my will, I had a further injection. Another psychiatrist came to see me at about 10:15am and she determined I could go…

“A smiling male nurse has just prodded my arm saying ‘everything will be OK, don’t hate Croatia now!” I have just discovered that I am at the University Hospital Vrapte. What to say?…Where I was looking for help, I got one of the worst twelve-hour experiences of my life.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”256″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Apr 2021 | Fellowship 2021, Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, a 2020 Freedom of Expression Awards winner

This week we were interviewing for a new member of the team to help support our work on the Freedom of Expression awards. The joy of interviewing for a new role is that it makes you reflect on what you do and why, even as you’re speaking to the candidates. As I was outlining the importance of the awards, I was reminded of why they are so incredibly important and not just for the winners, but also for the team. The fact is they give us hope, we get to show real solidarity with people who are on the frontline, people who every day are demanding their rights and protections under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Those people shortlisted for an award are typically unknown outside their countries, their stories untold. They have been jailed for campaigning for free speech. Hounded for using their talents as artists and writers to explore people’s realities under totalitarian regimes. Threatened for being journalists exposing corruption and repression at a national level. They are also just people who have found themselves in horrendous situations which they are determined to help fix.

Our award-winners and all of those nominated are extraordinary. They are inspirational. And they honestly keep the team going when day in and day out we are exposed to some of the horrors of what people are facing in too many places around the world, from Myanmar to Kashmir, from Afghanistan to Hong Kong, from Belarus to Xinjiang, from Komsomolsk-on-Amur to Greece.

It can be emotionally exhausting just trying to keep on top of what is happening in too many countries by too many authoritarian leaders. Soul-destroying to say today we have to focus on Egypt rather than Iran because we don’t have enough resource. The guilt that we aren’t doing enough or that we aren’t providing enough support or that the world has moved on and we can’t get traction for someone’s story. The world can just feel too depressing.

The Index team is extraordinary and resilient – but we all need a little hope.

And that’s what our awards do – they provide hope. The remind us of the struggles that people are prepared to fight and allow us to celebrate those people are fighting the good fight – so they know they are not alone, and that people genuinely care what happens to them.

Our award nominees and the eventual winners are extraordinary individuals but for the team at Index they embody our mission – to ensure that we are a Voice for the Persecuted. They represent the best of us, and we honour and support them not just because of who they are and what they have done – but because of what they represent. Bravery, resilience and determination for a better world.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]