Awards 2024 arts shortlist Aleksandra Skochilenko

ALEKSANDRA SKOCHILENKO Arts Award | Nominee | Freedom of Expression Awards Artist and musician Aleksandra Skochilenko was arrested on 11 April 2022. In response to Russia’s unlawful and full-scale invasion of Ukraine, she had participated in anti-war rallies (for...50 years on wounds still raw from Chile coup

Today, we mark the 50th anniversary of the coup that brought the right-wing dictator General Augusto Pinochet to power in Chile. The country remains deeply divided over Pinochet’s legacy and marches to pay tribute to the thousands of “disappeared” opponents of the regime this weekend ended in violence. Chile’s left-wing President Gabriel Boric attempted to use the anniversary as a moment of national unity, calling on all political parties to condemn the coup and celebrate democracy. He has failed to reach even this most basic consensus. According to polls, 36% of the Chilean people now believe the military was right to intervene to overthrow the Socialist government of Salvador Allende in September 1973.

Index on Censorship has always had a close relationship with Chile, particularly during the editorship of Andrew Graham-Yooll (1989-1994), who was an expert on South America. In 1991, a year after the peaceful handover of power to Pinochet’s successor, Patricio Aylwin, Index published an interview with the Chilean writer and opposition figure Ariel Dorfman, alongside the English translation of his play, Death and the Maiden. Dorfman had recently returned to his native Chile after many years in exile.

Already the fissures in Chilean society were clear. Graham-Yooll identified the difficulties faced by the Commission for Truth and Reconciliation set up to investigate the murders carried out by the Pinochet regime. “The role of the Commission was intended to be cautious and to limit the chance of antagonising the military,” wrote Graham-Yooll. “Survivors of the prisons and place of torment would not be considered. Testimony received could be with withheld from the public. Compensation to the victims would be decided in closed session of parliament.”

In the interview, Dorfman said there was a fundamental difficulty in societies transitioning from dictatorship to democracy. “Basically, there will always be a co-existence in many societies between those who committed crimes and those who were repressed. This co-existence is a fact of contemporary society. It does not happen only in the Chilean transition to democracy, which in its own way is very Chilean. It happens in all the transitions – in Eastern Europe and elsewhere. We call the situation created la impunidad – the state of impunity.”

Death and the Maiden captures Chile’s conundrum. A woman whose husband has been appointed to the Commission of Inquiry into the crimes of an authoritarian regime recognises one of her former torturers. The suspect denies his crimes, the woman craves revenge, and the husband must seek justice.

In 1991, the world was full of hope. The end of the Pinochet regime seemed to be part of a global shift towards a democratic consensus that included the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of apartheid. We have learnt to know better. As Dorfman was so quick to realise after his exile, the wounds remained raw and open. “We have to say ‘hello’ politely to our adversaries and there are topics we’d better not discuss, and wherever I scratched the surface I found this terrible pain,” he told Index.

It is clear from the events in Chile over the weekend that the “terrible pain” is still there 50 years after the coup. Chile is a democratic country now, but three decades of “truth and reconciliation” have not helped heal the divisions.

Our Autumn issue of the magazine, due out next week, contains two articles on the anniversary, including an interview and new short story from Ariel Dorfman. To purchase a copy click here

Ariel Dorfman interview: Writer unveils new short story lost after Chilean coup

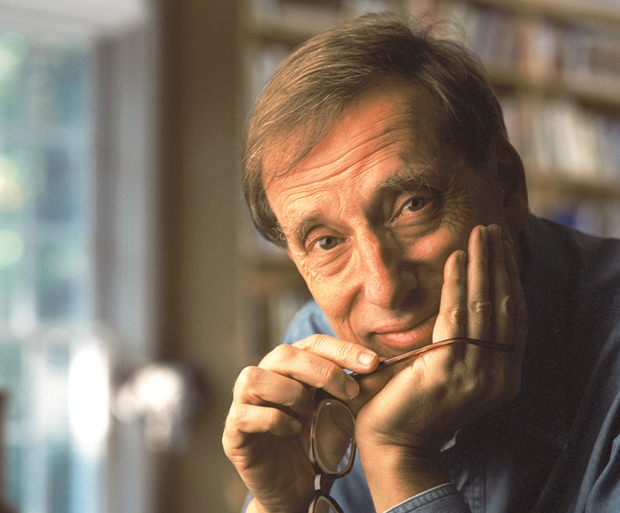

Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman

Fifty years ago, Chilean author Ariel Dorfman wrote down the seed of a story, which he then lost in his years of exile during General Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. Recently he revisited the idea and realised how to develop it into his new short story, All I Ever Have, which is published for the first time in the latest Index on Censorship magazine. Vicky Baker speaks to him about its key theme of music as resistance

Writer Ariel Dorfman remembers the exact moment the idea first came to him for his latest short story, All I Ever Have. It was 7 January 1966, his wedding day. As dawn broke over Chile, an image came into his mind of a man in a military band, playing a defiant, rebellious song on his trumpet. Just seven years later General Augusto Pinochet would seize power.

“Perhaps because I was so full of the music of the day, the positive songs of betrothal, that counter-image visited me that morning,” Dorfman said from his current home in the USA, where he is soon to celebrate his golden wedding anniversary with his wife, Angelica. The words he hastily scribbled down that morning were lost in Chile’s 1973 coup, when he was forced into exile, having supported the ousted president Salvador Allende and worked as his cultural adviser.

But the image of the lone musician never went away. “Only recently, I understood how to write it,” he said. “It was not only about the man who plays the trumpet but about what stays behind him, how the singer may die but not the song.”

Dorfman has always been interested in music as a form of resistance. He remembers Ode to Joy, from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, being sung in the streets of Santiago as a protest against Pinochet. Groups would assemble outside prisons to sing over the walls, and inmates who survived the torture there later spoke of the strength it gave them. Dorfman’s 1990 play Death and the Maiden, which was first published in English in Index on Censorship magazine, tells of a sadistic doctor who rapes a political prisoner to the sound of Schubert’s String Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, known as Death and the Maiden.

“Death and the Maiden echoes the horror that the commanders of Nazi concentration camps adored Beethoven,” he said. “I have been reflecting for a long time on music as a meeting place with those who are our adversaries and even enemies. That music is a territory that we share with many whose views we disagree with.”

In All I Ever Have, one of the most powerful moments comes when the soldier quietly whispers “You are not alone” to the dissenting trumpeter, just out of earshot of the anonymous general. Dorfman said the moment was informed by his years writing about human rights and talking with victims of torture. “I am always moved by a moment – an almost invariable moment – when each of them [the victims] says that, in jail, or after having been tormented, they realise they are not alone, not only because there are other prisoners nearby, but because the guards suddenly change their attitude, the guards become wary, as if they know they are being watched. This solidarity is almost like a physical wave that can be felt by those in need. It’s as if we were sending songs to the injured and insulted of the world, and they hear the songs, they really do.”

You can read the Ariel Dorfman’s new short story, All I Ever Have, in the latest Index on Censorship magazine. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year).

You can also find Index on Censorships Music as Resistance playlist here.

Ariel Dorfman’s latest novel in Spanish, Allegro, is narrated by Mozart in three crucial moments of his life (Editorial Stella Maris, November 2015)