3 May 2024 | Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Burma, Ethiopia, Georgia, Hong Kong, News, Opinion, Ruth's blog

With the world absorbed in too much news some important stories in the world of freedom of expression can be lost. As we mark World Press Freedom Day it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on what is really happening around the world, away from the daily news agenda, from the ‘foreign agent’ bill in Georgia, to the restrictions being placed on journalists in Myanmar, Ethiopia, Hong Kong and of course Afghanistan.

It’s one of these unheard stories which I want to focus on this week. In the ongoing global struggle for press freedom, Burkina Faso finds itself embroiled in controversy once again. The recent suspension of foreign media outlets over their coverage of a damning report accusing the country’s army of civilian massacres underscores an appalling trend towards censorship and repression.

The report, released by Human Rights Watch (HRW), alleges that Burkina Faso’s military was responsible for the killing of 223 civilians in retaliation for their support of armed Islamists. This accusation has been vehemently denied by the military government, which seized power in a coup in 2022 with the promise of quelling the Islamist insurgency plaguing the nation.

But instead of choosing light and transparency the government has chosen the tool of the tyrant – censorship.

Foreign media outlets such as the BBC, Voice of America, and Deutsche Welle have been suspended, their websites blocked, and broadcasts halted for daring to report on HRW’s findings. This outrageous approach to silencing truth and dissent stifles the flow of information and undermines the fundamental principles of freedom of expression.

The joint statement from the governments of the United States and United Kingdom unequivocally condemns Burkina Faso’s actions, emphasising the importance of an unfettered press in fostering informed public discourse. As we mark World Press Freedom Day, these acts of censorship serve as a stark reminder of the critical role that media plays in holding power to account and safeguarding democracy.

The suspensions imposed by Burkina Faso’s Superior Council of Communication not only violate the rights of journalists but also deprive the Burkinabe people of access to independent and accurate news. By blocking HRW’s website and restricting media coverage of their report, the government effectively shields itself from scrutiny and accountability.

Such tactics are not unique to Burkina Faso; they are part of a broader global trend towards authoritarianism and censorship. Across the world, journalists face intimidation, harassment, and violence simply for doing their jobs. This week, the BBC World Service has revealed for the first time that 310 of its journalists are living in exile.

The international community must stand in solidarity with journalists and media organisations under attack. Advocating for freedom of expression is not only a matter of principle but also a practical necessity for the functioning of democratic societies. When the voices of the oppressed are silenced, tyranny reigns unchecked.

As the world marks World Press Freedom Day, let us reaffirm our commitment to defending the rights of journalists everywhere. In the face of adversity, their courage and resilience serve as a beacon of hope for a brighter and more just future.

17 Jun 2021 | Africa, Burkina Faso, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré. (Koch/MSC/WikiCommons)

Burkina Faso is supposedly one of Africa’s gems when it comes to press freedom.

In a continent full of countries with extremely poor records on how they treat the media, the Western African state has, traditionally, set a better example. It is placed at number 37 on Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF’s) World Press Freedom Index, sitting between the United Kingdom at 33 and the United States at 44.

But some in the country are raising concerns.

In February two Spanish reporters, David Beriain and Roberto Fraile, and Irishman Rory Young, head of anti-poaching group Chengta Wildlife, were killed in an ambush. The group were filming a documentary highlighting wildlife poaching in the country. Illegal poaching in Burkina Faso is largely facilitated by organised criminal and terror groups who reside mainly in northern Burkina Faso in regions such as the Sahel.

The jihadist group Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen, an affiliate of al Qaeda, has claimed responsibility for the attack, according to AP. There is no suggestion that the journalists themselves were deliberately targeted but their deaths show the risks those reporting and working in the country face.

Another international journalist working in Burkina Faso, who wishes to remain anonymous, said: “The biggest threat to journalists is kidnapping, death or injury from Islamist terror groups. Second to that, it is local security forces and the state. There is no real threat of violence from them, but detention, deportation or obstruction of work are real concerns.”

The deaths of Beriain and Fraile seem to represent a watershed moment.

“In Burkina, the threat has certainly gotten worse in recent weeks,” the journalist said. “From March 2020 there was a period of relatively few attacks. I was certainly feeling more emboldened to go out to more remote areas of the countryside to report.”

“[But] since what happened to [these] journalists, as well as a recent spate of major attacks in the last few weeks, that has led me to reconsider where I will travel and for how long.”

Burkina Faso is also facing a displacement crisis. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs says “violence [has] led to the displacement of more than one million people in just two years and has left 3.5 million people in need of assistance, a 60 per cent increase from Jan 2020 to Jan 2021”.

In May, journalists were denied access to internally displaced people (IDP) sites, with the government citing the “safety and the dignity” of those in the camps. However, the safety and dignity of the displaced is clearly already under threat, with reports of sexual abuse against female IDPs.

“The threat from the state and security forces has certainly gotten worse,” the ISS report continued. “Two French journalists were quietly deported from the country last month a few days after they arrived.”

In early June, more than 100 people were reported killed by militants in Solhan, north-eastern Burkina Faso. Some 500 people have been killed in this region alone in 2021.

Questioning the reporting of the attack, the government announced 132 dead and reprimanded Radio France International, who reported 160 deaths.

President of the Association des journalistes du Burkina (AJB) Guézouma Sanogo says recent events are “unprecedented” and things are getting worse.

“Burkina Faso has been fighting terrorism since 2015. Journalists have since been threatened by telephone. Some have left their places of residence. Radio stations have closed in the Sahel. A radio station was even destroyed in the Sahel. But what happened in April 2021 is unprecedented. No journalist had yet been killed in the fight against terrorism in Burkina.”

Sanogo also pointed to increasingly restrictive legislation and says the country’s placement in the RSF index does not reflect the reality in the country.

In 2015, the ABJ accused the government of president Roch Marc Christian Kabore (pictured top) of interfering in the professional duties of journalists when it issued a directive to state broadcaster RTB to prioritise coverage of the head of state.

Even before that, press freedom has been under attack for decades.

In 1998, the investigative journalist Norbert Zongo, publishing director of the Independent, was assassinated in the country. “There has so far been no justice in this matter,” says Sanogo.

“RSF’s ranking is undoubtedly based on the laws which adopted in September 2015 and decriminalise press offences. But these laws have instituted very heavy fines for journalists in the range of 500,000 FCFA to 3,000,000 FCFA (£650 to £4,000).”

“Since then, the government has also passed laws criminalising coverage of terrorist attacks by journalists.”

Indeed, in 2019, the National Assembly of Burkina Faso introduced a reform to its penal code which stated that journalists and others can receive up to ten years’ imprisonment for reports that “demoralise” soldiers when reporting any military information regarding troop movements or weapons.

The amendment was introduced “to reduce the threat from terrorism”.

The Burkina Faso-based journalist who spoke to Index does not feel restricted by the country’s legislation.

They said: “The legislation for a free press in Burkina Faso actually looks quite good on the surface.”

“There is a prevailing culture here where journalists often self-censor and avoid certain subjects. Although there is little legislation to limit access to places or subjects, in practice there’s a large number of unwritten rules and obstructions which can land you in trouble if you do not abide by them.”

The deaths of David Beriain and Roberto Fraile may well have been collateral damage in the escalating fight between Burkina Faso’s military and Islamist groups but, even if that is the case, the situation for journalists in the country remains precarious.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Mar 2018 | Africa, Artistic Freedom, Burkina Faso, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

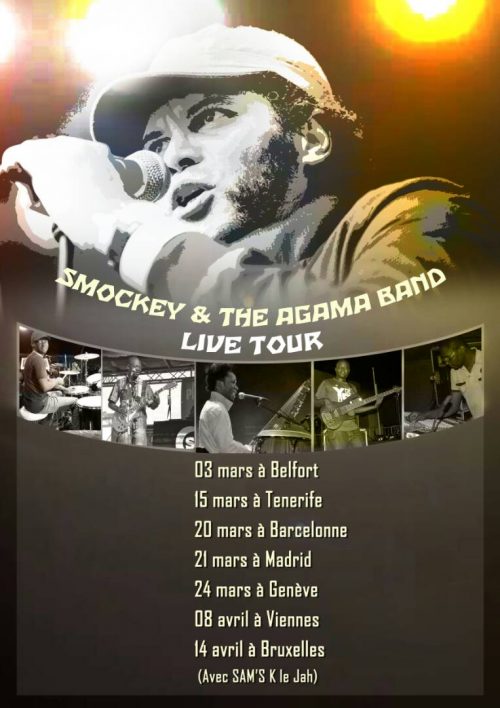

Music in Exile Fellowship Winner Serge Bambara, aka Smockey (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

On 3 March in Belfort, France, Burkinabe rapper and activist Smockey began a two-month long European tour, despite having his studio destroyed twice in recent years. The rapper, whose given name is Serge Bambara, was the inaugural Index on Censorship Music in Exile Fellow in April of the same year. Just three months after the awards, his recording studio, Studio Abazon, was wrecked in a devastating fire.

“All my music files since 2001, including my master tapes and those of my productions and clients, were lost,” Smockey told Index in September 2016. Two years on, it remains unclear how the fire began.

Smockey’s studio was also bombed in September 2015 by armed forces loyal to Burkina Faso’s former president Blaise Compaoré. This was a vengeful attack for his political activism and music critical of Compaoré’s regime.

Despite these aggressive and censorious acts, Smockey continues to record and perform, combating different forms of injustice with each track. As the founder of the grassroots political movement Le Bilai Citoyen, which helped to oust Compaoré, he often promotes the progressive ideas of Burkina Faso’s former socialist leader Thomas Sankara. The Sankarist ideology involves advocating for women’s rights, fighting corruption and imperialism, and upholding the integrity of Burkinabe people, all of which are reflected in Smockey’s lyrics. La Bilai Citoyen translates as the “the citizen’s broom,” which is “a tribute to Thomas Sankara, who organised weekly street-cleaning sessions,” Smockey told the BBC.

In March 2018 Smockey told news website Africa is a Country that Sankara’s image was that of “simplicity, modesty, and integrity … a model for anyone aspiring to manage public property”. He also noted that Sankara had the “courage and determination to build a Burkina Faso of social justice and inclusive development.”

Although the uprising of 2015 was successful in ridding Burkina Faso of an oppressive twenty-seven-year regime, Smockey is not an enthusiastic supporter of the country’s current government led by the progressive former opposition leader Roch Marc Christian Kaboré. Smockey is still a watchdog for human rights violations within his country. “The ones who were our friends before the revolution can be our enemies today,” he told Quartz Africa in July 2016. “We helped them have this power, but we are not friends because we are still sentinels.” For example, his song Tomber la Lame takes aim at widespread Female Genital Mutilation throughout Africa.

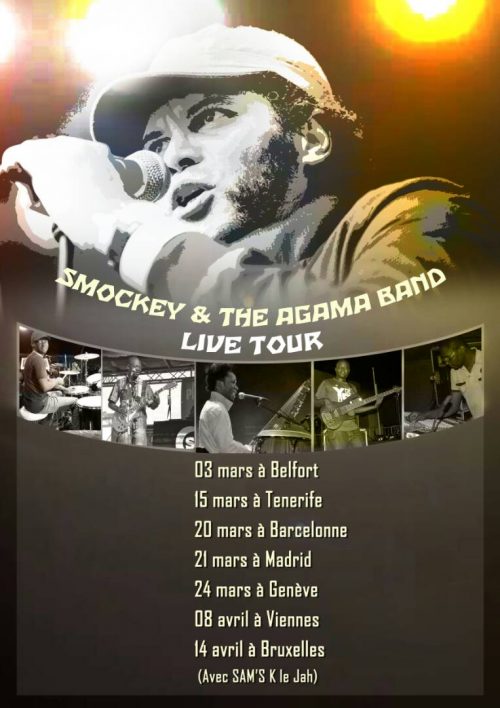

Despite multiple attempts to stop his political and artistic expression, Smockey continues to create and share his music globally. Over six weeks he will perform throughout Europe, finishing his tour in Brussels, Belgium, on 14 April.

Smockey’s European Tour Dates and Locations 2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522161604778-9ae9ecbc-682f-8″ taxonomies=”8072″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Jul 2025 | Africa, Burkina Faso, Chad, DR Congo, Gabon, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, News, Niger, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sudan, Togo

The 2020s have been a busy time for military coups in Africa.

University of Kentucky political scientists Jonathan Powell, who specialises in the study of political instability, and Professor Clayton Thyne, whose research focuses on domestic conflict and coups d’état, said there were 13 attempted coups in Africa in the years 2021 to 2023.

Powell says eight of those coups succeeded – in Chad, Mali, Guinea and Sudan in 2021, two separate coups in Burkina Faso in 2022, one on 23 January of that year and another on 30 September, and in Niger and Gabon in 2023..

The remaining five coups failed: in Niger and Sudan in 2021, in Guinea-Bissau and São Tomé and Príncipe in 2022 and in Sudan in 2023. In the latter, the military rulers who had seized power in 2021 continued to run the war-torn country.

Where the military have been successful in taking control, the army generals leading the coups have since shown no appetite for a return to civilian rule despite promising to do so when they took control..

Two of the coup leaders – Chad’s military leader Mahamat Idriss Déby, who seized power in 2021,and Gabon’s General Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema who masterminded a coup in 2023 – have since held disputed elections in an attempt to give their rule a measure of legitimacy. In May 2024, Déby swept the presidential polls with more than 60% of the vote while Nguema won with 90% of the vote in April this year.

The effects of these coups have been devastating: brutal repression marked by arbitrary detentions, torture, disappearances, and extrajudicial killings to stifle political dissent.

There has also been corruption, erosion of free speech and strained relations with neighbouring countries or former colonial powers in some instances.

Promises to restore security, revitalise the economy or champion the will of the people that were invariably given as a motivation to seize power have been substituted by measures to entrench the rule of the military dictatorships.

Powell said the wave of coups have a common thread, a reluctance to relinquish power and erosion of rights such as free speech.

“The big takeaway is that previously coup leaders or the armed forces typically retreated from power, and often very quickly. This has radically shifted since 2021. Since then, all coups have seen the coup leaders remain in power,” he told Index.

“The coups since 2021 occurred within varying contexts, but major commonalities are other forms of domestic instability, civil war, violence, political manipulation and governments’ loss of legitimacy in the eyes of their people even with [previously] elected leaders “

In those countries where coups have seen the de facto establishment of military rule, freedoms in general are suffering, with journalists and media freedom in particular coming under attack.

“We have seen the arbitrary arrest of journalists in different countries, while Mali’s junta has attempted to virtually ban political coverage altogether,” Powell added.

Mali, Burkina Faso, and Gabon offer a study in how military rulers are corrupted by power, becoming worse or more brutal than the regimes they overthrew.

Mali’s transitional military government, which seized power in May 2021, announced that scheduled elections would be delayed indefinitely for technical reasons.

The military government also suspended political parties, a development the human rights watchdog said violates both Malian law and the rights to freedom of expression, association, and assembly under international human rights law.

Human Rights Watch also said that Mali’s council of ministers has adopted a decree directing all media to stop “broadcasting and publishing the activities” of political parties and associations.

In the case of Burkina Faso, coup leader Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Damaogo Damiba became interim president in January 2022 but was ousted by Captain Ibrahim Traoré in a subsequent coup nine months later.

Traoré pledged to restore the civilian government by 1 July 2024 but last year he extended the transition period by another five years, adding that he would be eligible to contest the elections.

In Gabon, according to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, the country is on track to swap one form of autocratic governance with another. The military regime of Brigadier General Brice Oligui Nguema, who seized power in a coup on 30 August 2023, has instituted a “sequence of actions to pave an unobstructed pathway to claim the presidency” in upcoming elections.

This includes appointing loyalists to two-thirds of the Senate and National Assembly, appointing all nine members of the Constitutional Court, hosting a tightly scripted national dialogue process in mid-2024, from which 200 political parties were banned and rewriting of the constitution to allow members of the military to contest political office, and extend presidential terms to seven years.

An activist from Niger, Dr Mayra Djibrine, told Index that since the July 2023 coup in her country led by General Abdourahamane Tiani, there has been a rise in arbitrary arrests and detentions of political opponents, activists, and journalists.

Djibrine said while military leaders may justify coups as necessary measures to restore order or combat corruption, history has shown that military governance often leads to prolonged instability.

She said the military leaders in Niger have announced their intentions to transition to civilian rule but have not specified a concrete timeline for elections but given the uncertainty and historical precedents in the region, skepticism remains about how soon Niger will revert to a stable civilian government.

“The military regime has imposed restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly, accompanied by heightened surveillance and censorship of media outlets critical of the government. Additionally, ongoing insecurity due to extremist violence in certain regions has further complicated the human rights landscape. Humanitarian access has also been limited in some areas, worsening the plight of those in need,” said Djibrine.

“Freedom of speech in Niger is facing significant challenges in the wake of the coup. While there was some degree of media freedom prior to the coup, the current military government has implemented measures that stifle dissent and control public discourse. Journalists are often subjected to intimidation, harassment, and detention for reporting critically on the regime. Access to independent media has been increasingly limited, and public protests against the government are met with a strong repressive response. This environment has led to self-censorship, diminishing the space for open dialogue and critical expression.”

She said to prevent coups throughout Africa, several approaches could be considered that include building robust democratic institutions that ensure citizen representation and accountability can help reduce discontent and the likelihood of military takeovers.

She said this involves not only conducting credible elections but also promoting transparency within the government.

She said there is also a need to strengthen the role of civil society organisations to enhance public engagement and create mechanisms for citizens to collaboratively voice their concerns, thus reducing disillusionment with political systems.

“Reforming security forces to ensure they operate under civilian authority and focus on national defense rather than political ambitions is crucial. Prioritising military professionalism is essential for building trust between civilians and the armed forces,” she said.

In July 2023, as the world was witnessing an uptick in coups in African countries, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) released a report titled Soldiers and Citizens: Military Coups and the Need for Democratic Renewal in Africa as part of its partnership with the African Union Commission which offered insights into what fuels coups in Africa.

The report said readily exploitable grievances, linked to African leaders’ failures to deliver inclusive development as they rule behind a façade of democracy while deploying innately exclusionary models of governance has created fertile ground for coups to be staged on the continent.

It said there is a correlation between heightened coup risk and stagnant growth, exclusionary economic governance, multidimensional poverty, inequality, reduced youth and women’s participation, governance deficits, among others.

The findings confirm that coup risk can be viewed as a subset of state fragility. Countries that experience contemporary coups perform poorly on global development indices. These rankings are not abstract, but represent millions of lives marred by exclusion, infringement of rights, restriction of opportunity and frustration. These grievances create a base of frustration that coup leaders can readily exploit,” the report said.

Nick Watts, the vice president of EuroDefence UK told Index that the countries affected by coups have been courted by China and Russia who are playing on anti-colonial sentiment.

He said a Russian proxy, the Wagner Group, has been providing the means of removing governments deemed too close to their former colonial masters.

Watts said Wagner has continued operating in the region even after the death of its former powerful leader Yevgeny Prigozhin.

He offered an explanation on why these coups have taken place.

“The regimes have been seen as out of touch, which has played into the hands of ‘liberation’ movements,” he said.

The desire for power in Africa has not diminished.

In May 2024, a failed coup took place in the Democratic Republic of the Congo while other African dictators, such as Togo’s Faure Gnassingbé who ruled the country from 2005 after he was installed by the army when his autocratic father Gnassingbé Eyadéma died, changed the constitution to prolong his rule. Gnassingbé, whose family has ruled the country for nearly six decades, was sworn into a new post of President of the Council of Ministers which has no official term limits, a move which sparked deadly protests.

While the 2020s have been a particularly fertile period for coups in Africa, it continues a historical precedent. The UNDP report says there have been 98 coups in Africa between 1952 and 2022, more than one a year.

The report’s authors said that to mitigate coup risk, African governments must strive to deliver better governance, deepen democracy and inclusive development.

It called on regional and international actors to engage proactively with countries where presidents are nearing the end of their term limits to secure public assurances that they will resign and allow for a peaceful transfer of power. History tells us that Africa’s military leaders are unlikely to listen.