16 Sep 2014 | Magazine, Volume 43.03 Autumn 2014

Index on Censorship autumn magazine

In the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine, don’t miss: Burmese-born author Wendy Law-Yone on the challenges the Burma’s media face in the run-up to the next election; TV journalist Samira Ahmed on how television channels should respond to viewers’ complaints; award-winning foreign correspondent Iona Craig reports from Yemen on threats to journalism in conflict zones; plus a brand new short story from playwright and author Ariel Dorfman.

While debates on the future of the media tend to focus solely on new technology and downward financial pressures, we ask: will the public end up knowing more or less? Will citizen journalists bring us in-depth investigations? Will crowd fact-checking take over from journalists doing research? Who will hold power to account? The subject is tackled from all angles, from our writers from across the globe.

Also writing for this issue are Australia’s race commissioner Tim Soutphommasane; human rights lawyer Tamsin Allen on defamation; and novelist Kaya Genc. From South Korea Steven Borowiec talks to controversial artist Lee Ha, and in London political editor Ian Dunt walks the corridors of political power in the UK’s Houses of Parliament and asks if journalists there get too close to government.

Other articles include:

- African digital journalism by Ray Joseph

- Generation why by Ian Hargreaves

- Funding news freedom by Glenda Nevill

You can buy the print version magazine or subscribe for £31 per year here, or download a digital version for your iPad for just £1.79. All subscriptions help fund Index’s work, protecting freedom of expression worldwide.

Read about our magazine launch at the Frontline Club on 22 October.

FULL CONTENTS: ISSUE 43, 3 – The future of journalism

Back to the future: Iona Craig on journalists trying to stay safe in war zones

Digital detectives: Ray Joseph on the new technology helping Africa’s journalists investigate

Re-writing the future: Five young journalists talk on their hopes and fears for the profession – from Yemen, India, South Africa, Germany and the Czech Republic

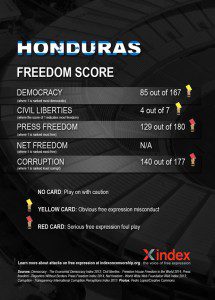

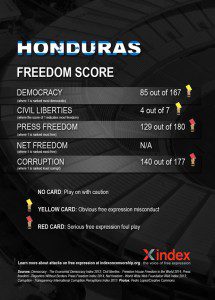

Attack on ambition: Dina Meza on a Honduran generation ground down by fear

Stripsearch cartoon: Martin Rowson envisages an investigative reporter meeting Deep Throat

Generation why: Ian Hargreaves asks on how the powerful may or may not be held to account in the future

Making waves: Helen Womack reports from Russia on the radio station standing up for free media

Switched on and off: US journalist Debora Halpern Wenger on TV’s power shift from news producers to news consumers

TV news will reinvent itself (again): Taylor Walker interviews a veteran TV reporter on the changes ahead

Right to reply: Samira Ahmed on how the BBC tackles viewers’ criticism

Readers as editors: Stephen Pritchard on how news ombundsmen create transparency

Lobby matters: Political reporter Ian Dunt on the push/pull of journalists and politicians inside Britain’s corridors of power

Funding news freedom: Glenda Nevill looks at innovative ways to pay for reporting

Print running: Will Gore on how newspapers innovate for new audiences

Paper chase: Luis Carlos Díaz on overcoming Venezuela’s newsprint shortage

IN FOCUS

Free thinking? Australia’s race commissioner Tim Soutphommasane on bigotry

Guarding the guards: Jemimiah Steinfeld on China’s human rights lawyers becoming targets

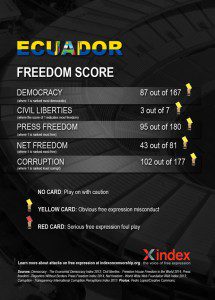

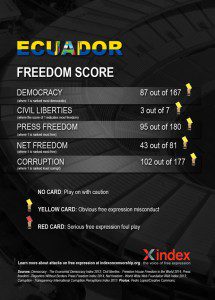

Taking down the critics: Irene Caselli investigates allegations that Ecuador’s government is silencing social media users

Maid equal in Brazil: Claire Rigby on the Twitter feed giving voice to abuse of domestic workers in Brazil

Home truths in the Gulf: Georgia Lewis on how UAE maids fear speaking out on maltreatment

Text messaging: Indian school books are getting “Hinduised”, reports Siddarth Narrain from India

We have to fight for what we want: our editor, Rachael Jolley, interviews the OSCE’s Dunja Mijatovic on 20 years championing free speech

Decoding defamation: Lesley Phippen’s need-to-know guide for journalists

A hard act to follow: Tamsin Allen gives a lawyer’s take on Britain’s libel reforms

Walls divide: Jemimah Steinfeld speaks to Chinese author Xiaolu Guo about a life of censorship

Taking a pop: Steven Borowiec profiles controversial South Korean artist Lee Ha

Mapping media threats: Melody Patry and Milana Knezevic look at rising attacks on journalists in the Balkans

Holed up in Harare: Index’s contributing editor Natasha Joseph reports from southern Africa on the dangers of reporting in Zimbabwe

Burma’s “new” media face threats and attack: Burma-born author Wendy Law-Yone looks at news in the run up to the impending elections

Head to head: Sascha Feuchert and Charlotte Knobloch debate whether Mein Kampf should be published

CULTURE

Political framing: Kaya Genç interviews radical Turkish artist, Kutlug Ataman

Action drama: Julia Farrington on Belarus Free Theatre and the upcoming Belarus election

Casting away: Ariel Dorfman, a new short story by the acclaimed human rights writer

ALSO

Index around the world: Alice Kirkland gives a news update on Index’s global projects

From the factory floor: Vicky Baker on listening to the world’s garment workers via new technology

18 Jun 2014 | Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Middle East and North Africa

GROUP A

GROUP B

GROUP C

GROUP D

GROUP E

GROUP F

GROUP G

GROUP H

This article was published on June 18, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Mar 2014 | Americas, News and features, United States

(Image: Free Barrett Brown)

On 7 March, a US federal judge granted the government’s motion to dismiss the majority of its criminal case against journalist Barrett Brown. The 11 dropped charges, out of 17 in total, include those related to Brown’s posting of a hyperlink that led to online files containing credit card information hacked from the private US intelligence firm Stratfor.

Brown, a 32-year old writer who has had links to sources in the hacker collective Anonymous, has been in pre-trial detention since his arrest in September 2012 – weeks before he was ever charged with a crime. Prior to the government’s most recent motion, he faced a potential sentence of over a century behind bars.

The dismissed charges have rankled journalists and free-speech advocates since Brown’s case began making headlines last year. The First Amendment issues were apparent: are journalists complicit in a crime when sharing illegally obtained information in the course of their professional duties?

“The charges against [him] for linking were flawed from the very beginning,” says Kevin M Gallagher, the administrator of Brown’s legal defense fund. “This is a massive victory for press freedom.”

At issue was a hyperlink that Brown copied from one internet relay chat (IRC) to another. Brown pioneered ProjectPM, a crowd-sourced wiki that analysed hacked emails from cybersecurity firm HBGary and its government-contracting subsidiary HBGary Federal. When Anonymous hackers breached the servers of Stratfor in December 2011 and stole reams of information, Brown sought to incorporate their bounty into ProjectPM. He posted a hyperlink to the Anonymous cache in an IRC used by ProjectPM researchers. Included within the linked archive was billing data for a number of Statfor customers. For that action, he was charged with 10 counts of “aggravated identity theft” and one count of “traffic[king] in stolen authentication features”.

On 4 March, a day before the government’s request, Brown’s defence team filed its own 48-page motion to dismiss the same set of charges. They contended that the indictment failed to properly allege how Brown trafficked in authentication features when all he ostensibly trafficked in was a publicly available hyperlink to a publicly available file. Since the hyperlink itself didn’t contain card verification values (CVVs), Brown’s lawyers asserted that it did not constitute a transfer, as mandated by the statute under which he was charged. Additionally, they argued that the hyperlink’s publication was protected free speech activity under the First Amendment, and that the application of the relevant criminal statutes was “unconstitutionally vague” and created a chilling effect on free speech.

Whether the prosecution was responding to the arguments of Brown’s defense team or making a public relations choice remains unclear. The hyperlink charges have provoked a wave of critical coverage from the likes of Reporters Without Borders, Rolling Stone, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the New York Times, and former Guardian columnist Glenn Greenwald.

Those charges were laid out in the second of three separate indictments against Brown. The first indictment alleges that Brown threatened to publicly release the personal information of an FBI agent in a YouTube video he posted in late 2012. The third claims that Brown obstructed justice by attempting to hide laptops during an FBI raid on his home in March of that year. Though he remains accused of access device fraud under the second indictment, his maximum prison sentence has been slashed from 105 years to 70 in light of the dismissed charges.

While the remaining allegations are superficially unrelated to Brown’s journalistic work, serious questions about the integrity of the prosecution persist. As indicated by the timeline of events, Brown was targeted long before he allegedly committed the crimes in question.

On 6 March 2012, the FBI conducted a series of raids across the US in search of material related to several criminal hacks conducted by Anonymous members. Brown’s apartment was targeted, but he had taken shelter at his mother’s house the night prior. FBI agents made their way to her home in search of Brown and his laptops, which she had placed in a kitchen cabinet. Brown claims that his alleged threats against a federal officer – as laid out in the first indictment, issued several months later in September – stem from personal frustration over continued FBI harassment of his mother following the raid. On 9 November 2013, Brown’s mother was sentenced to six months probation after pleading guilty to obstruction of justice for helping him hide the laptops – the same charges levelled at Brown in the third indictment.

As listed in the search warrant for the initial raid, three of the nine records to be seized related to military and intelligence contractors that ProjectPM was investigating – one of which was never the victim of a hack. Another concerned ProjectPM itself. The government has never formally asserted that Brown participated in any hacks, raising the question of whether a confidential informant was central to providing the evidence used against him for the search warrant.

“This FBI probe was all about his investigative journalism, and his sources, from the very beginning,” Gallagher says. “This cannot be in doubt.”

In related court filings, the government denies ever using information from an informant when applying for search or arrest warrants for Brown.

But on the day of the raids, the Justice Department announced that six people had been charged in connection to the crimes listed in Brown’s search warrant. One, Hector Xavier Monsegur (aka “Sabu”), had been arrested in June 2011 and subsequently pleaded guilty in exchange for cooperation with the government. According to the indictment, Sabu proved crucial to the FBI’s investigation of Anonymous.

In a speech delivered at Fordham University on 8 August 2013, FBI Director Robert Mueller gave the first official commentary on Sabu’s assistance to the bureau. “[Sabu’s] cooperation helped us to build cases that led to the arrest of six other hackers linked to groups such as Anonymous,” he stated. Presuming that the director’s remarks were accurate, was Brown the mislabeled “other hacker” caught with the help of Sabu?

Several people have implicated Sabu in attempts at entrapment during his time as an FBI informant. Under the direction of the FBI, the government has conceded that he had foreknowledge of the Stratfor hack and instructed his Anonymous colleagues to upload the pilfered data to an FBI server. Sabu then attempted to sell the information to WikiLeaks – whose editor-in-chief, Julian Assange, remains holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London after refusing extradition to Sweden for questioning in a sexual assault case. Assange claims he is doing so because he fears being transferred to American custody in relation to a sealed grand jury investigation of WikiLeaks that remains ongoing. Though Sabu’s offer was rebuffed, any evidence linking Assange to criminal hacks on US soil would have greatly strengthened the case for extradition. It was only then that the Stratfor data was made public on the internet.

During his sentencing hearing on 15 November 2013, convicted Stratfor hacker Jeremy Hammond stated that Sabu instigated and oversaw the majority of Anonymous hacks with which Hammond was affiliated, including Stratfor: “On 4 December, 2011, Sabu was approached by another hacker who had already broken into Stratfor’s credit card database. Sabu…then brought the hack to Antisec [an Anonymous subgroup] by inviting this hacker to our private chatroom, where he supplied download links to the full credit card database as well as the initial vulnerability access point to Stratfor’s systems.”

Hammond also asserted that, under the direction of Sabu, he was told to hack into thousands of domains belonging to foreign governments. The court redacted this portion of his statement, though copies of a nearly identical one written by Hammond months earlier surfaced online, naming the targets: “These intrusions took place in January/February of 2012 and affected over 2000 domains, including numerous foreign government websites in Brazil, Turkey, Syria, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Nigeria, Iran, Slovenia, Greece, Pakistan, and others. A few of the compromised websites that I recollect include the official website of the Governor of Puerto Rico, the Internal Affairs Division of the Military Police of Brazil, the Official Website of the Crown Prince of Kuwait, the Tax Department of Turkey, the Iranian Academic Center for Education and Cultural Research, the Polish Embassy in the UK, and the Ministry of Electricity of Iraq. Sabu also infiltrated a group of hackers that had access to hundreds of Syrian systems including government institutions, banks, and ISPs.”

Nadim Kobeissi, a developer of the secure communication software Cryptocat, has levelled similar entrapment charges against Sabu. “[He] repeatedly encouraged me to work with him,” Kobeissi wrote on Twitter following news of Sabu’s cooperation with the FBI. “Please be careful of anyone ever suggesting illegal activity.”

While Brown has never claimed that Sabu instructed him to break the law, the presence of “persons known and unknown to the Grand Jury,” and whatever information they may have provided, continue to loom over the case. Sabu’s sentencing has been delayed without explanation a handful of times, raising suspicions that his work as an informant continues in ongoing federal investigations or prosecutions. The affidavit containing the evidence for the March 2012 raid on Brown’s home remains under seal.

In comments to the media immediately following the raid, Brown seemed unfazed by the accusation that he was involved with criminal activity. “I haven’t been charged with anything at this point,” he said at the time. “I suspect that the FBI is working off of incorrect information.”

This article was posted on March 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Nov 2013 | Americas, News and features

While president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s government took a hit during midterm elections, Argentina’s supreme court ruled her restrictions on the country’s media were constitutional. (Photo: Claudio Santisteban / Demotix)

The Argentinian supreme court recently ruled to uphold the country’s controversial media law. The decision represents a big victory for President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who argued that the law helps break up the power concentrated in the hands of Argentina’s biggest media conglomerate Grupo Clarín. Opponents, however, says it stifles freedom of expression and press as it would force media companies to sell off some of their outlets. Concerns have also been raised about the law being a way of punishing Clarín, which fell out with the government after negative coverage during tax protests in 2008.

This is only the latest chapter in the ongoing story of the media business in some Latin American countries, with left wing governments and private companies locked in a decade-long fight for control of what will be shown on TV, heard on the radio, printed in newspapers, and posted on websites. New communications laws, persecution of journalists and closure of television networks, however, shows who is really in charge.

Governments like Venezuela and Argentina are waging war against big media companies, while more moderate ones, like Brazil, are using milder means to try and balance the power of communication in their countries. But far from being presented as a straightforward issue of freedom of expression, most of these cases have two opposing and radical interpretations.

On one side, there is the pro-government camp. They believe the governments are democratising the media, which has traditionally been in the hands of the few. In Brazil, for example, eight families control almost 80% of all traditional media companies. The aforementioned Grupo Clarín owns national and regional newspapers, radios, TV channels and more.

Those opposing these measures, however, say they amount to censorship. Again, a good example comes from Argentina: there are some rumours that Kirchner’s administration is trying to suffocate Grupo Clarín by not allowing big chain stores to advertise in their papers. There is also the infamous case of the the closure of Venezuela TV channel RCTVI in 2010.

Both sides talk of freedom of expression, arguing they want to show what is better for the public. But the public – those with the most to benefit from a good and transparent media – are not being allowed to decide for themselves. This is not happening just in Argentina and Venezuela, but across the continent – in Ecuador, Nicaragua and Bolivia, and, albeit in a much gentler way, in Brazil.

Professor Mirta Varela, specialist in history of the media at the University of Buenos Aires, is among those who believe governments are not repressing the big companies or trying to dominate the industry. “The measures taken have shown the political and economic power of the main companies, the spurious origin of their economic growth and their relationship with the dictatorship”, she explains, referencing Grupo Clarín and the military regimes that held power in almost all the Latin American countries from 1960 to 1980. But she also sees some problems with this polarisation: “There is a little room to set a new agenda; to make independent criticism, not overtly for or against the government.”

Cecilia Sanz works for Argentinian TV show “Bajada de línea”, which roughly translates to “Under the Line”. The show is hosted by Uruguayan Victor Hugo Morales, a well-known journalist connected to what Sanz calls “the progressive governments” in Latin America. Here she groups together a number of different left-leaning governments from across the continent – from moderates Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, to the more radical Evo Morales in Bolivia and Rafael Correa in Ecuador.

The show comments on the state of the media in Latin America, mainly arguing against the big private companies. “Our main goal is to put in context and show how the media owners have the intention, above all else, to accomplish their economic objectives,” she says. “The are using ‘freedom of expression’ as an excuse for this”. She mentions the case of powerful Mexican TV Azteca, which according to her, supports all the candidates from the hegemonic party PRI, and Chilean paper “El Mercurio”, which used to attack Chilean ex-president Salvador Allende in the 1970s – again putting very different cases in the same group.

The more radical of these “progressive governments” accuse the media industry of trying to destabilise the authorities or to encourage coups d’état. Venezuela’s putsch in 2002 is always mentioned. In this case factions of the media was directly fighting against Hugo Chávez – so Chávez took them off the air.

“This is an insult to the audience because in all of cases it is about the most popular media channels”, counters Claudio Paolillo, president of the freedom of press and expression commission of SIP, Sociedad Interamericana de Prensa (the Inter-American Press Society). “No one has put a gun to the audience’s head to force them to choose what to read, listen or watch, and on what channel.”

Paolillo says the government engages in “Goebbels’ style” propaganda, sustained by public resources, to oppress independent or critic media and journalists. He adds that, ironically, these radical “progressive governments” act like the conservative military regimes of the past. “It is an ideological posture. They want to nationalise communications media as if it was a regular business that offers services or products.”

Paolillo says SIP is against Latin Americas state-controlled monopolies or oligopolies, but reaffirms it is the audience that has the real power to decide what to watch, and where. If they want to watch the same news program, the government shall not interfere. “Unfortunately in Argentina as in Venezuela (and we must add here Ecuador, Nicaragua and Bolivia), governments have created their own media companies, expropriated and bought private ones – in some cases even working through a figurehead”, he complains.

Brazilian political scientist Mauricio Santoro brings up another common problem in the region – organised crime targeting reporters in Mexico and Colombia. But he says this is not a new situation. In his opinion, what is new, is “progressive governments” using the power of the state to control its opponents.

“The alternative proposed by these leftist governments is not based on the construction of an alternative model that privileges pluralism and gives a voice to social and community movements. It is about breaking business groups and giving power to a state press that acts like a government representative and not a public one.”

Worried about the poor quality of the media across Latin America, Santoro suggests the continent needs a more dynamic media, more capable of listening and understanding the true necessities of the people of a region going through “profound change”.

“Looking at the local scene”, he asks, “are we able to find any country where the traditional media meets this expectation?”

Not really.

This article was originally posted on 11 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org