25 Jun 2021 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116995″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]It’s a year since I joined the Index family.

I think for all of us the last 12 months have been an emotional rollercoaster. The impact of Covid-19 has been a cloud over our lives; we’ve lost people close to us, we’ve all feared the effect of a virus no one had heard of 18 months ago, we’ve missed our loved ones and we’ve looked on in horror at events both at home and abroad as political leaders have both failed to manage the pandemic and undermined basic human rights under the guise of public health protections.

Repressive leaders have moved against their citizens, we’ve witnessed coups, heard testimony from detention camps and totalitarian regimes have restricted freedoms to an even greater extent throughout the world. And we’ve seen some of the most important vehicles of media freedom undermined – from Rappler to the Apple Daily.

It’s been difficult not to feel impotent. We haven’t been able to travel to stand with those being oppressed. Democratic countries have understandably focused their efforts on their domestic challenges and the institutions we depend on to enforce our shared norms as outlined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights have been distracted by the global public health emergency. In other words, it has felt that totalitarian leaders have had a free pass to enforce even harsher restrictions on their peoples.

At Index, even despite the pandemic, we’ve strived to shine a spotlight on some of the most egregious attacks on free expression around the globe. In the last 12 months, we’ve supported journalists, writers, artists and academics in over two dozen countries. We’ve published reports on the impact of Covid-19, the current use of SLAPPs to undermine journalists and on online harms. Index has held events exploring the impact of 100 years of CCP rule in China, as well as on the untold stories hidden by Covid-19 and the impact of AI on social media content. And nearly three quarters of a million people have engaged with our work.

We’ve rebranded, redesigned the magazine and have completely changed our annual Freedom of Expression awards and we’ve started the celebrations to mark our 50th birthday. All of this and our team have only met in person three times, as we continue to do our work from home.

I’m so proud of the Index family, they have adapted and continue to push the envelope, making sure that no dictator can think that the world isn’t watching and that activists around the world know that we have their back. There is so much work to do in the months and years ahead in the ongoing battle for free speech, but after working with the team for a year I don’t doubt that we are making a positive difference, highlighting the bravest campaigners in the world and with your help – providing a voice for the persecuted.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Aug 2020 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A screenshot of Merdan Ghappar from the video he filmed on his phone from a Chinese prison

In a video clip that went viral yesterday, Uighur model Merdan Ghappar doesn’t speak. But he doesn’t need to – the footage says enough. Shot by Ghappar himself from inside a prison cell, he moves the camera with one hand and reveals his other to be handcuffed to a bed. Ghappar is confined to a tiny room with mesh and bars on a window. His clothes are dirty as are the walls, and his face carries an expression of anguish and exhaustion.

Ghappar is incarcerated in one of China’s notorious prisons for Uighurs, the Muslim population who live in the far western province of Xinjiang. The Uighurs, with their Islamic faith, Turkic language and ties to the cultures of central Asia, have long been viewed by the Chinese state with suspicion and have faced discrimination. Following two brutal attacks against pedestrians and commuters in Beijing in 2013 and in Kunming in 2014, which were blamed on Uighur separatists, this suspicion has morphed into systematic oppression.

Estimates suggest more than one million Uighurs are now incarcerated in a network of prisons across the region. China initially denied the existence of the prisons, then acknowledged them but said they were re-education camps established to counter extremism in the province. The state denies Uighurs are being used as forced labour and denies rumours of torture and other abuses. The camps are also winding down, the state has recently said.

It can be hard to probe the official Chinese party line: foreign media is pretty much banned from Xinjiang. Reporters who have been there have found their visas revoked, such as Buzzfeed’s China bureau chief Megha Rajagopalan, who was forced to leave China in 2018. Rajagopalan had reported extensively on the crackdown in Xinjiang. When media is allowed in, as the BBC has been, the visits are highly controlled and staged.

But with each passing week and month evidence that directly contradicts the party line finds its way into the outside world; shipments of human hair products from Xinjiang reach New York; drone footage of rows of people queuing, shackled and blindfolded, for trains appears; testimonies of sterilisation of Uighur women emerge. And now Merdan Ghappar’s video. It might be the most significant piece of evidence yet.

Sure it does not come close to showing the real horror of the camps, but it does something else. It personalises the Uighurs’ plight. We see his face; we look into his eyes. And through his video and the reports that have emerged around it we learn his own, unique story.

We know that Ghappar studied dance at Xinjiang Arts University and worked as a dancer before he became a successful model. We know that in 2009, he moved away from Xinjiang in search of other opportunities in China’s wealthier eastern cities. We know, from his relatives, that he was told to downplay his Uighur identity and refer to his facial features as “half-European” if he wanted to get ahead in his career. And we know that he was also apparently unable to register the apartment he bought with his own money in his own name, instead having to use the name of a Han Chinese friend. We know that throughout this period Ghappar was in regular touch with his uncle, Abdulhakim Ghappar, who fled China after his activism in Xinjiang made him a target (in 2009, for example, he handed out flyers ahead of a large-scale protest in the city of Urumqi), and that while his uncle says Ghappar is not political, his ties to his uncle might explain why he became a target.

We know that in August 2018 he was arrested and sentenced to 16 months in prison for selling cannabis, a charge many believe is false. We know he was released in November 2019, but that soon after police told him he needed to return to Xinjiang to complete a routine registration procedure and that there “he may need to do a few days of education at his local community”.

We know that on 15 January, his friends and family brought clothes and his phone to the airport where he boarded a flight and was escorted by two officers back to his home city of Kucha. And most significantly, we know that he somehow managed to not only keep, but use his phone and from this reveal some details of his own incarceration (initially in a squalid, unsanitary prison jail where he was surrounded by the sounds of other inmates screaming; later in the facility shown in the new video he says his “whole body is covered in lice”).

But we don’t know where he is today. Ghappar’s messages have stopped. No one has heard from him and authorities have not provided notification of his whereabouts.

There is an increasingly loud chorus of calls for what is happening in Xinjiang to be labelled a genocide – and this could definitely change how the international community responds to the situation. But as history has proved even if it is officially termed a genocide will it force us, on an individual level at least, to act differently?

Comparisons to the Holocaust come easily and one line of defence there, which has come up again and again, is that people didn’t act because people “didn’t know”. But that’s historically contested given how ubiquitous the camps were. There was a reason people on arrival at Auschwitz tried to rouge their cheeks to appear healthy – they knew.

What some historians have argued, though, which could partly explain the inaction of many, is that while people might have known, they didn’t understand. The truth was simply too abhorrent to fathom. And without understanding they didn’t truly know.

And that’s why Ghappar’s video and story is so important. As was the case with Anne Frank, and indeed recently with George Floyd, sometimes you need a face, a singular experience, to relate to the suffering of the whole. Stories that are granular touch people in ways that the bigger picture cannot always. News of the ill treatment of Uighurs is not new and yet within hours of Ghappar’s video circulating, crowds began protesting outside the Chinese Embassy in London.

Ghappar has made the Uighur suffering feel much more real and more personal. He could be our brother, our son, our neighbour, our friend. He’s not just a number or a news headline; he’s a face and a name. Let’s learn that name and tell his story. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Apr 2020 | News and features, Volume 49.01 Spring 2020 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Misinformation is everywhere and I don’t know who to trust, writes a Chinese writer, based in Nanjing” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_single_image image=”113000″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Wuhan doctor Li Wenliang told several of his friends in Chinese social media app WeChat to be careful because some patients had caught a SARS-like disease in his hospital. Within hours of this message being sent it had gone viral – without his name being removed. Li was then accused of rumour mongering. He was called to a local police station and reprimanded. But, not jailed, he returned to work, only to contract coronavirus himself. He died on 7 February.

In the wake of the outbreak of coronavirus, the internet police in China first tried to block information about the disease to maintain society order. This was what Li fell victim to. Then, as the situation became out of control, the main target of censorship moved to suppressing negative coverage, as China tried to position itself as a model country in the fight against coronavirus. There was no bad news, even though there was clearly bad news. Did people believe this positive coverage? It’s hard to tell. Looking at related topics on Sina Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, most comments have been complimentary. After the lockdown of Wuhan, the local medical system was overburdened. People who couldn’t get treatment asked for help on the internet, but the number of such messages fell from being in the thousands each day initially to hardly any later. Pictures of chaotic scenes in hospitals were removed.

The coronavirus is now storming throughout the world at an increasing speed and scale. It has greatly impeded global activities, as if a pause button on life has been pressed.

As the disease has spread around China, something else has been on the move – the intensification of censorship. While censorship existed before coronavirus, it has rapidly increased since then. And I fear this increase in censorship will not stop soon, even if the virus does.

During this time I have been in Nanjing, a former capital city near Shanghai. All I have been able to do is to watch official news and online discussions to see the latest development of the situation. But in China, where the news is tightly controlled, it’s really hard to identify the correct information. Misleading information is everywhere and you don’t know who to trust. I have felt helpless and the only thing I securely know I can do is to stay at home with family and pray for safety.

At the same time, there has been anger over the censoring of important information. In a recent interview published in the magazine Renwu, Ai Fen, head of the emergency department in a major hospital in Wuhan, recounted her experience. She told the magazine that she was the first to alert other people about the novel virus but was told by her hospital not to spread this information, not even to her husband. The article published on Renwu was quickly removed. And yet there have been many translated versions of the original, including in German, English, even Braille. We won’t let her testimony be deleted.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”She told the magazine that she was the first to alert other people about the novel virus but was told by her hospital not to spread this information, not even to her husband. The article published on Renwu was quickly removed.” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The impact of such severe censorship during this critical time has been catastrophic. The censorship carried out by the authorities during coronavirus is not vastly different to that that happens during other sensitive periods, such as around the Tiananmen Square anniversary, except that coronavirus is a global public health crisis, as pointed out by Lotus Ruan, a researcher from Citizen Lab. The censorship of neutral and even factual information related to the virus, which is completely unnecessary, might have limited the public’s ability to share and discuss critical knowledge of how to prevent the virus’ spread. For example, many elderly Chinese people refused to wear masks at the early stage of spread because the government claimed that the disease was preventable, containable and curable and there was no evidence that the virus was contagious between people. Even my grandparents thought I was making a big deal out of the virus.

There was a crucial time-lag of several weeks between when the first doctors started to notify people of the virus and when the authorities actually allowed it to be openly discussed and taken seriously.

China is now starting to come out of quarantine. And just in time for the traditional festival, Qingming, which was this weekend and commemorates the deceased. Residents in the city of Wuhan were allowed to take their departed family’s ashes from the funeral parlor. And yet we were all puzzled. Many web portals and social media platforms received orders not to report news about this, and there were security officers at sites to stop people taking photos. Such action has added more grief to this tragic scene. “The crowd were so quiet. No crying. No dirge. They just left with an urn in silence”, wrote someone on Weibo.

I am lucky. Nanjing has been a relatively safe place since the outbreak. Very few have been infected and as yet there have been no reported deaths. As for the residents of Wuhan, we can’t help but ask: have these people lost their right to mourn?

On 19 March, the official investigation on Li Wenliang’s death was released. It called for Li’s reprimand to be withdrawn and for two policemen who were involved in Li’s arrest to be warned as a punishment and response to the incident. Obviously, this is not enough in the view of the public. The true cause of Li’s tragedy is the deeply rooted censorship which has become a part of daily life. Anyone could be the next Li Wenliang.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The author of this piece is a freelance journalist based in Nanjing, China.

Index on Censorship’s spring 2020 issue is entitled Complicity: Why and when we chose to censor ourselves and give away our privacy

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

1 Mar 2018 | China, News and features

With the historic announcement at the weekend that China would end the two-term limit on presidents, meaning the current leader Xi Jinping could be president for life, it created an online storm.

People took to the popular Chinese social media apps Weibo and WeChat to express either disdain and outrage. It didn’t take too long for the country’s well-oiled censorship apparatus to swing into action and ban all of the obvious terms related. Within hours, you couldn’t say “I don’t agree”, “migration”, “emigration”, “re-election”, “election term”, “constitution amendment”, “constitution rules”, “proclaiming oneself an emperor”, “Yuan Shikai (Former Emperor)” and “Winnie the Pooh” (more on this soon).

At the same time, Chinese citizens created and widely shared a series of memes. Most of these have since been removed, but not before enough people saw them, screenshots were taken and they were spread on media beyond the censor’s reach. Here’s an overview of some of the best:

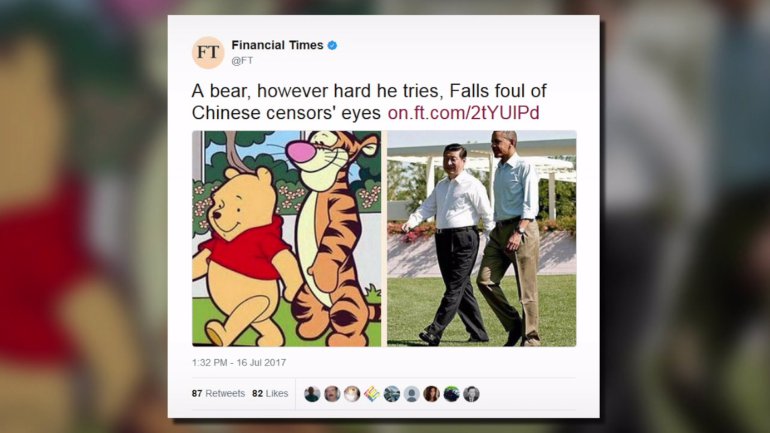

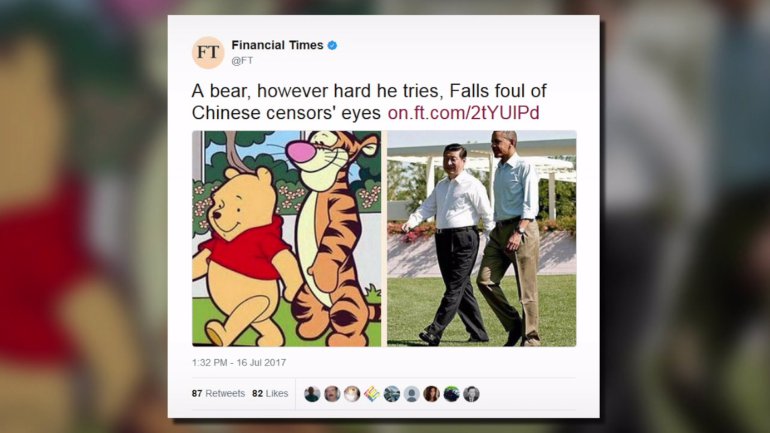

King Winnie

The world’s favourite cuddly teddy bear, unless you’re a Chinese leader. After a meme likened the cartoon character with the Communist Party leader went viral in 2013, Winnie the Pooh became a popular meme when riffing Xi – and arguably the world’s most censored children’s book character. That has not stopped people persisting with the animated representation of the leader. In response to the new proposal, several of the following memes circulated:

The original meme that prompted the government to ban Pooh in 2013.

Another oldie but goodie expressing Xi’s disdain for Pooh, created by cartoonist Badiucao in the China Digital Times.

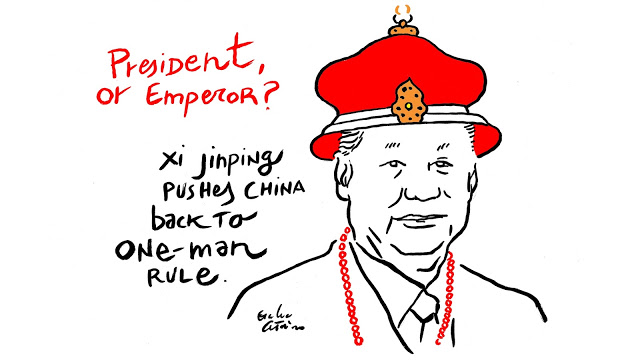

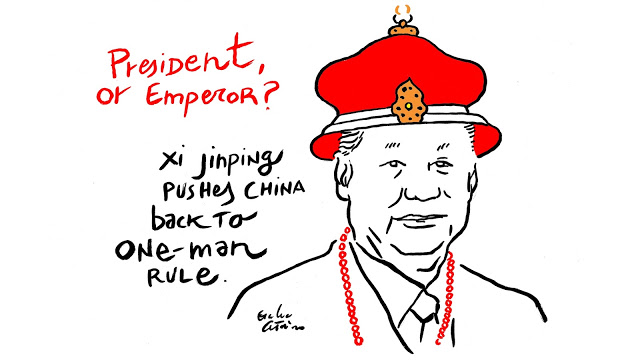

Emperor Xi

An obvious one here. Graphics emerged with references to past emperors of China, emphasizing the point that this new proposal is reminiscent of past Chinese rulers and dictators. Some of these graphics censored include:

Cartoon created on political activism website, ChannelDraw.

Graphic created after the announcement by Badiucao, prolific political activist and cartoonist.

Silver lining?

Perhaps the best of the memes, combining as it does a joke about Xi’s term extension and a joke about the common Chinese pressure to get married. It reads: “My mom said that I have to get married before Xi Dada’s term in office ends. Now I can breathe a long sigh of relief.”

Don’t forget the bunnies

While the latest news is sure to keep the censors busy for some time, they’ve been waging another war in China this year against #Metoo, which has recently come to the country and has not been well-received by a government uncomfortable with any form of protest (read our article on protest in China here). Initially the hashtag #woyeshi went viral, which literally means “me too”. When that was banned, people got creative. Introducing the rice bunny. Rice in Mandarin is mi and bunny tu, pronounced basically “me too”. Now China’s internet is awash with images of bunny and rice combos, that is until the censors catch up. Bunnies and Pooh bears – China’s internet might be censored, but it’s never boring.

The Rice Bunny is against sexual harassment. Image from @七隻小怪獸 on Weibo