1 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Governments are using the Covid-19 crisis to change freedom of information laws and, unless we are very careful, important stories could get unreported. Since the beginning of the crisis, governments from Brazil to Scotland have made changes to their FOI laws; some of the changes are rooted in pragmatism at this unprecedented time; others may be inspired by more sinister motives.

FOI laws are a vital part of the toolkit of the free media and form a strong pillar that supports the functioning of open societies.

According to a 2019 report by Unesco – published some two and a half centuries after the first such law was introduced in Sweden – 126 countries around the world now have freedom of information laws. These typically allow journalists and the general public the right to request information relating to decisions made by public bodies and insight into administration of those public bodies.

US president Thomas Jefferson once wrote: “Whenever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights.”

Now in this time of crisis, freedom of information processes are being shut down, denied unless they relate specifically to the crisis or the deadlines for responses are being extended.

When the Covid-19 crisis first erupted, we made a decision to monitor attacks on media freedom. It wasn’t just a random idea; we know that in similar times of crisis, repressive governments often attack the work that journalists do – sometimes the journalists themselves – or introduce new legislation they have wanted to do for some time and now see a time of crisis as an opportunity to do so without proper scrutiny.

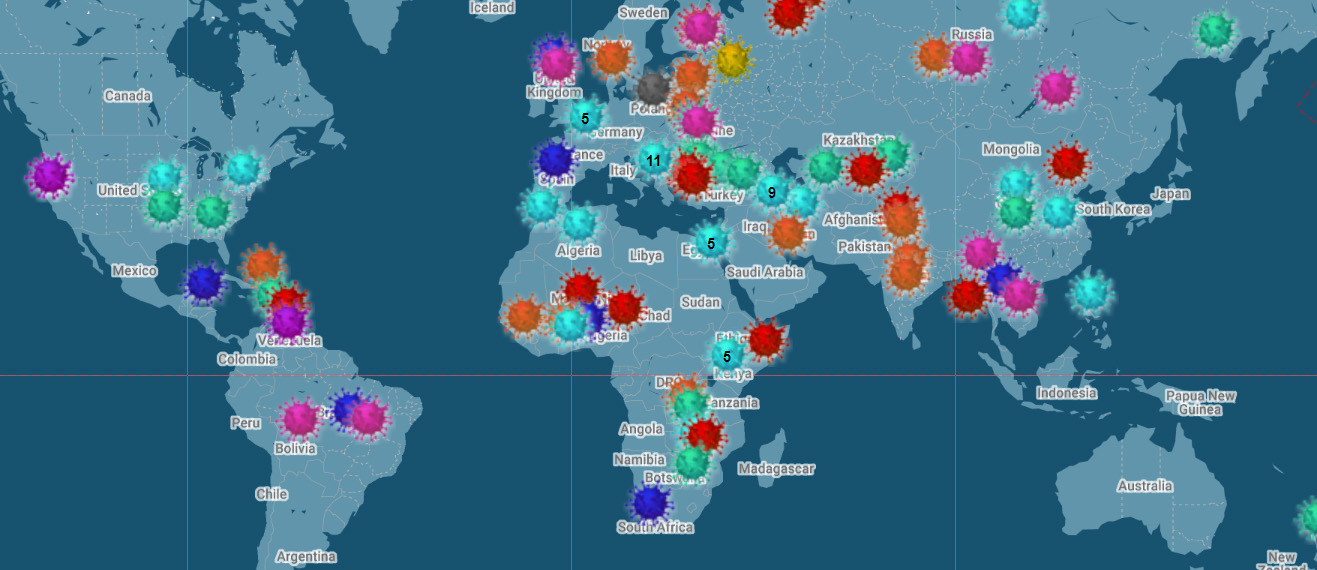

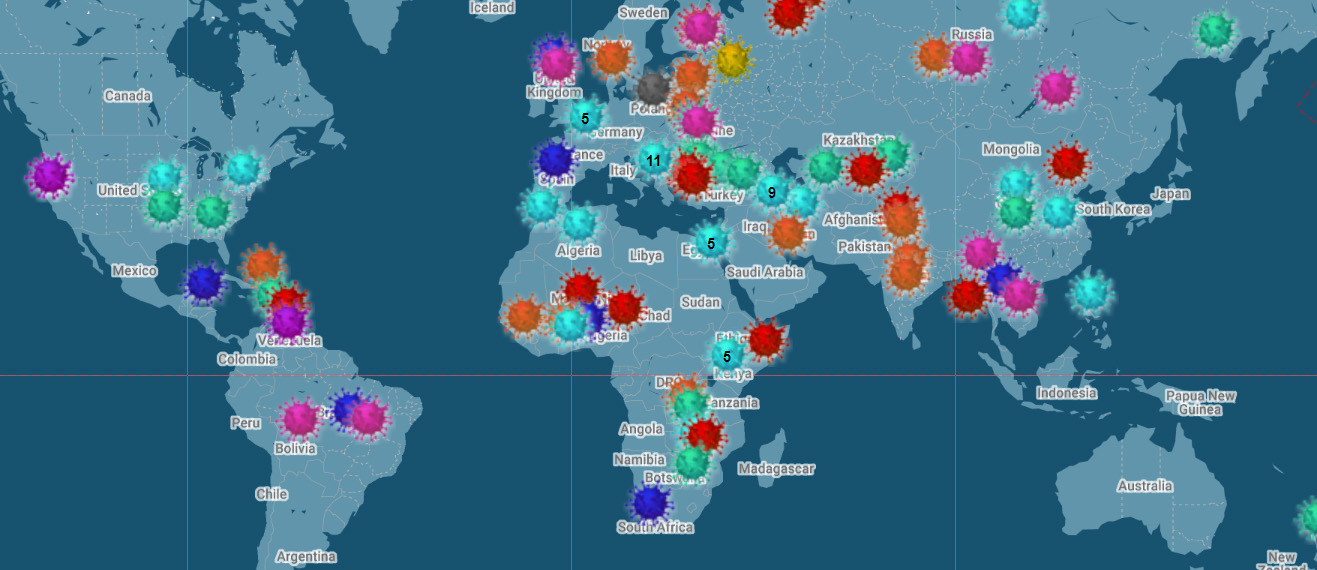

Since the start of the crisis, we have been collecting reports on attacks on media freedom through an innovative, interactive map. More than 125 incidents have been reported by our readers, our network of international correspondents, our staff in the UK and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation. Many relate to changes to FOI legislation.

Let us be clear there can be legitimate reasons for amending legislation in times of international crisis. With many public officials forced to work from home, many do not have access to the information they need or the colleagues they need to consult to be able to answer journalists’ requests. Others need more time to be able to put together an informed response.

Yet both restrictions and delays are worrying. They allow politicians and public bodies to sweep information that should be freely available and subject to wider scrutiny under the carpet of coronavirus. News that is three months old is, very often, no longer news.

In its Coronavirus (Scotland) Bill, the Scottish government has agreed temporary changes to the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 that extend the deadlines for getting response to information requests from 20 to 60 working days. The initial draft wording sought to allow some agencies to extend this deadline by a further 40 days “where an authority was not able to respond to a request due to the volume and complexity of the information request or the overall number of requests being dealt with by the authority”. However, this was removed during the reading of the bill following concerns raised by the Scottish information commissioner.

The bill was passed unanimously on 1 April and became law on 6 April. As it stands the new regulations remain in force until 30 September 2020 but can be extended twice by a further six months.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has issued a provisional measure which means that the government no longer has to answer freedom of information requests within the usual deadline. Marcelo Träsel of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism says the measure is “dangerous” as it gives scope for discretion in responding to requests.

The decree compelled 70 organisations to sign a statement requesting the government not to make the requested changes, saying “we will only win the pandemic with transparency”.

Romania and El Salvador are among the other countries which have stopped FOI requests or extended deadlines. By contrast, countries such as New Zealand have reocgnised the importance of FOI even in a crisis. The NZ minister of justice Andrew Little tweeted: “The Official Information Act remains important for holding power to account during this extraordinary time.”

FOI law changes are not the only trends we have noticed.

Index’s deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld has noted how world leaders are ducking questions on coronavirus while editorial assistant Orna Herr has written about how the crisis is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims.

If you are a journalist facing unreasonable delays in receiving information from public bodies at this time, do report it to us at bit.ly/reportcorona.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Aug 2019 | Academic Freedom, China, News, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/b21faoXVpM4″][vc_column_text]“Students in the United States must be free to express their views, without feeling pressured to censor their speech…We can and will push back hard against the Chinese government’s efforts to chill free speech on American campuses.” This is what Marie Royce, US assistant secretary of state for educational and cultural affairs, said in her address welcoming Chinese students to American universities in July 2019.

As much a warning as a welcome, the speech illustrates the balancing act America and other western countries often perform when engaging with Chinese people and organisations on campus. The presence of the Chinese Communist Party on campuses severely limits the free expression of Chinese students, and threatens more broadly to curtail academic freedom, the right to protest, and the ability to engage with the uncomfortable truths about the Chinese government honestly.

To understand the situation, one must first understand the unique nature of the party apparatus. The CCP attempts to control not only China’s political arena but every aspect of Chinese citizens’ lives, at home and abroad, including on US campuses. Dr Teng Biao, a well-known Chinese human rights activist and lawyer, tells Index on Censorship: “It’s quite unique. The party’s goal is to maintain its rule inside China at all costs, and so it sets about making the world safe for the CCP. It is all-directional.”

That control looks very different abroad than it does at home. CCP does not control much of its foreign influence network directly. “It has different ways of implementing influence,” Teng explains. Some Chinese organisations “are directed by the Chinese government and don’t have much independence in making decisions.” However, other organisations, such as alumni networks and Chinese businesses, as well as Chinese students, have their own agency and goals, and operate largely independently.

Sources from US intelligence agencies to the New York Times have reported that the Confucius Institutes, which teach Chinese language skills to non-Chinese people, and the Chinese Students and Scholars Associations, which are student-led organisations that provide resources for Chinese students and promote Chinese culture, are directed by the CCP. The CSSA has worked closely with Beijing to promote its agenda and suppress critical speech. According to Royce, “there are credible reports of Chinese government officials pressuring Chinese students to monitor other students and report on one another” to officials, and the CSSA often facilitates this spying.

Similarly, the Confucius Institutes, have a history of stealing and censoring academic materials, have been accused of attempting to control the Chinese studies curriculum, and have been implicated in what FBI director Cristopher Wray recently described to Congress as “a thousand plus investigations all across the country” into possible CCP-directed theft of intellectual property on campuses.

Beijing’s influence is perhaps the most indirect and complex with regard to Chinese students themselves. The same day Royce made her welcome address, 300 Chinese nationalists disrupted a demonstration against China’s Hong Kong extradition bill at the University of Queensland, Australia, leading to violent clashes. On 7 August 2019 more violence between detractors of the extradition law and supporters of the CCP occurred at the University of Auckland, New Zealand, in what China’s consul general in Auckland calls a “spontaneous display of patriotism”. Earlier this year, Chinese students at MacMaster University in Canada, incensed by a lecture on the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uigher ethnic minority, allegedly filmed the event and sent the video to the Chinese consulate in Toronto, which denied involvement but praised their actions as patriotic. [/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/kW3c211dy8g”][vc_column_text]Speaking to Index about the Queensland protest, Dr Jonathan Sullivan, director of China Programs at the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute, said “Many Chinese students have passionately held views and they sometimes mobilise to voice them. I don’t think it’s helpful to see such mobilisations as being the work of the party, although there is also evidence that party/state organisations sometimes provide help.” Sullivan notes, however, that their passion and convictions “are themselves a product of the authoritarian information order created by the party-state” and that “there is among Chinese students potential to react in an organised way.”

Isaac Stone Fish, a prominent journalist and a senior fellow at the Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations in New York City told Index “[The party is] very effective generally at keeping students in an ideological framework,” convincing them, for instance, that “the communist party and China are the same” and thus motivating them to protect the party. However,he agrees that students’ convictions belong to them. “It’s ok for Chinese students to feel that Beijing’s policies are correct,” he says. Problems only arise when they try to control the conversation.

As the extent of the CCP’s influence is gradually revealed to the public, there have been fears that governments will retaliate indiscriminately and restrict visas for all Chinese students abroad, or withhold them specifically from members of the CSSA. Tensions over immigration, especially in the US, mean such a reaction is possible, but as Sullivan says: “We should keep in mind that most Chinese students care about their degree and getting on in life, and we all must resist any temptation to homogenise — let alone demonise — them.” Stone Fish concurs. “There is…a danger of a racially-tinged backlash against Chinese people, which would be an ethical and strategic mistake.”

Sullivan is concerned that many universities treat Chinese students like an easy source of income instead of treating them as students with unique and pressing needs. They have that in common with the party itself. One of the biggest dangers in dealing with the CCP, explains Stone Fish, is “its willingness to use Chinese students as bargaining chips” directing them to some universities and way from others to encourage political conformity. Western institutions are vulnerable to such a tactic, Teng claims, because they “care about money more than universal values,” and “They don’t profoundly realise” that the CCP “has become an urgent threat.”

So far, the western response to the issue has been inconsistent and uncertain. “I think universities need to develop a much clearer understanding of the issues,” Sullivan says. “These can be complex and university administrators are not generally China specialists who are able to identify the nuances, which makes policy and provision inadequate and potentially unbalanced.” Going forward, Stone Fish asserts, we should be “Educating college administrators about how the party works,” and “having universities work together.” Cooperation is essential, because “Beijing prefers to negotiate one-on-one,” but as a bloc, Universities have leverage of their own.

Demand for western education in China is strong and continues to grow, especially among the Chinese elite and middle class. However, universities can only use that demand to resist pressure from the CCP if they coordinate their response. Stone Fish concludes, “I think the greatest danger is giving in to Beijing’s demands not to have certain speakers, or allow the party to prevent certain voices from being heard.” [/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1566913121795-e09fc4f8-7d31-10″ taxonomies=”8843″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Feb 2019 | Artistic Freedom, Artistic Freedom Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Press Releases, Statements, Uganda

More than 130 musicians, writers and artists, together with many British and Ugandan members of parliament, have signed a petition calling on Uganda to drop plans for regulations that include vetting songs, videos and film scripts prior to their release. Musicians, producers, promoters, filmmakers and all other artists would also have to register with the government and obtain a licence that can be revoked for a range of violations.

Index on Censorship is deeply concerned by these proposals, which are likely to be used to stifle criticism of the government.

“Around the world from Cuba to Indonesia and Uganda, artists are being pressured by governments seeking to control their art and their message. These misplaced efforts are an intolerable intrusion into artistic freedom and must not be enacted,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index said.

Signatories to the letter include U2’s Bono and Adam Clayton, author Wole Soyinka, and Razorlight’s Johnny Borrell.

Full text of the letter follows:

Uganda’s government is proposing regulations that include vetting new songs, videos and film scripts, prior to their release. Musicians, producers, promoters, filmmakers and all other artists will also have to register with the government and obtain a licence that can be revoked for a range of violations.

We, the undersigned, are deeply concerned by these proposals, which are likely to be used to stifle criticism of the government.

We, the undersigned, vehemently oppose the draconian legislation currently being prepared by the Ugandan government that will curtail the freedom of expression in the creative arts of all musicians, producers and filmmakers in the country.

The planned legislation includes:

- All Ugandan artists and filmmakers required to register and obtain a licence, revokable for any perceived infraction.

- Artists required to submit lyrics for songs and scripts for film and stage performances to authorities to be vetted.

- Content deemed to contain offensive language, to be lewd or to copy someone else’s work will be censured.

- Musicians will also have to seek government permission to perform outside Uganda.

Contained in a 14 page draft Bill that bypasses Parliament and will come before Cabinet alone in March to be passed into law, any artist, producer or promoter who is considered to be in breach of its guidelines shall have his/her certificate revoked.

This proposed legislation is in direct contravention of Clause 29 1a b of the Ugandan

Constitution which states:

- Protection of freedom of conscience, expression, movement, religion,

assembly and association.

(1) Every person shall have the right to—

(a) Freedom of speech and expression which shall include freedom of the media;

(b) Freedom of thought, conscience and belief which shall include academic

freedom in institutions of learning;

Furthermore, in accordance with Clause 40 (2)

(2) Every person in Uganda has the right to practise his or her profession and to

carry on any lawful occupation, trade or business.

As a Member State of the African Union, the Republic of Uganda has ratified the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Article 9 of the Charter provides:

- Every individual shall have the right to receive information.

- Every individual shall have the right to express and disseminate his opinions within the law.

We therefore call upon the Ugandan government to end this grievous and blatant

violation of the constitutional rights of Ugandan artists and producers, and to honour

its international obligations as laid down in the various international human rights

conventions to which Uganda is a signatory and for Uganda to uphold freedom of speech.

Background

- Although freedom of expression is protected under the Uganda constitution, it is coming under increasing threat in the country.

- In 2018, authorities arrested popular musician and opposition member of parliament, Robert Kyagulanyi, better known as Bobi Wine. He was badly beaten in military custody. Musicians, writers and social activists including Chris Martin, Angelique Kidjo, U2’s The Edge, Damon Albarn and Wole Soyinka, signed a petition calling for his release, which ultimately succeeded.

- Since July 1, Ugandans have had to pay a tax of 200 shillings, about 5 US cents, for every day they use services including Facebook, Twitter, Skype and WhatsApp.

- The government said it wanted to regulate online gossip, or idle talk but critics fear this meant it wanted to censor opponents.

- During the presidential election in 2016, officials blocked access to Facebook and Twitter

- On Thursday January 31 a statement was made by Jeremy Hunt MP, the UK’s Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs: “”We are aware of the proposed regulations to the Ugandan music and entertainment industry that are currently being consulted on and are yet to be approved by the Cabinet. The UK’s position is that such regulations must not be used as a means of censorship. The UK supports freedom of expression as a fundamental human right and, alongside freedom of the media, maintains that it is an essential quality of any functioning democracy. We continue to raise any concerns around civic and political issues directly with the Ugandan government.”

ABTEX – Producer, Uganda

ADAM CLAYTON – Musician, U2

ALEX SOBEL – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

AMY TAN – Novelist, Screenwriter

ANDY HEINTZ – Freelance journalist and author, USA

ANISH KAPOOR – Artist, United Kingdom

ANN ADEKE – Member of Parliament, Uganda

ANNU PALAKUNNATHU MATTHEW – Artist, USA and India

ASUMAN BASALIRWA – Member of Parliament, Uganda

AYELET WALDMAN – Writer

BELINDA ATIM – Uganda Sustainable Development Initiative

BILL SHIPSEY – Founder, Art for Amnesty

BONO – Musician, U2

BRIAN ENO – Artist, Musician and Producer

BRUCE ANDERSON – Journalist Editor/Publisher

CLAUDIO CAMBON – Artist/Translator, France

CRISPIN BLUNT – Member of Parliament and former Chair of Foreign Affairs Select Committee, United Kingdom

DAN MAGIC – Producer, Uganda

DANIEL HANDLER – Writer, Musician aka Lemony Snicket

DAVID FLOWER – Director, Sasa Music

DAVID HARE – Playwright

DAVID SANCHEZ – Saxophonist and Grammy Winner

DEBORAH BRUGUERA – Activist, Italy

DELE SOSIMI – Musician – The Afrobeat Orchestra

DOCTOR HILDERMAN – Artist, Uganda

DR VINCENT MAGOMBE – Journalist and Broadcaster

DR PAUL WILLIAMS – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

EDDIE HATITYE – Director, Music In Africa

EDDY KENZO – Artist, Uganda

EDWARD SIMON – Musician and Composer, Venezuela

EFE OMOROGBE – Director Hypertek, Nigeria

ERIAS LUKWAGO – Lord Mayor of Kampala Uganda

ELYSE PIGNOLET – Visual Artist, USA

ERIC HARLAND – Musician

FEMI ANIKULAPO KUTI – Musician, Nigeria

FEMI FALANA – Human Rights Lawyer, Nigeria

FRANCIS ZAAKE – Member of Parliament, Uganda

FRANK RYNNE – Senior Lecturer British Studies, UCP, France

GARY LUCAS – Musician

GERALD KARUHANGA – Member of Parliament, Uganda

GINNY SUSS – Manager, Producer

HELEN EPSTEIN – Professor of Journalism Bard College

HENRY LOUIS GATES – Director of the Hutchins Center at Harvard University

HUGH CORNWELL – Musician

IAIN NEWTON – Marketing Consultant

INNOCENT (2BABA) IDIBIA – Artist, Nigeria

IRENE NAMATOVU – Artist, Uganda

IRENE NTALE – Artist, Uganda

JANE CORNWELL – Journalist

JEFFREY KOENIG – Partner, Serling Rooks Hunter McKoy Worob & Averill LLP

JESSE RIBOT – American University School of International Service

JIM GOLDBERG – Photographer, Professor Emeritus at California College of the Arts

JODIE GINSBERG – CEO, Index on Censorship

JOEL SSENYONYI – Journalist, Uganda

JON FAWCETT – Cultural Events Producer

JON SACK – Artist

JOHN AJAH – CEO, Spinlet

JOHN CARRUTHERS – Music Executive

JOHN GROGAN – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

JONATHAN LETHEM – Novelist

JONATHAN MOSCONE – Theater Director

JONATHAN PATTINSON – Co-Founder Reluctantly Brave

JOHNNY BORRELL – Singer, Razorlight

JOJO MEYER – Musician

KADIALY KOUYATE – Musician, Senegal

KALUNDI SERUMAGA – Former Director – Uganda National Cultural Centre/National Theatre

KASIANO WADRI – Member of Parliament, Uganda

KEITH RICHARDS OBE – Writer

KEMIYONDO COUTINHO – Filmmaker, Uganda

KENNETH OLUMUYIWA THARP CBE – Director The Africa Centre

KING SAHA – Artist, Uganda

KWEKU MANDELA – Filmmaker

LAUREN ROTH DE WOLF – Music Manager Orchestra of Syrian Musicians

LEMI GHARIOKWU – Visual Artist, Nigeria

LEO ABRAHAMS – Producer, Musician, Composer

LES CLAYPOOL – Musician, Primus

LINDA HANN – MD Linda Hann Consulting Group

LUCIE MASSEY – Creative Producer

LUCY DURAN – Professor of Music at SOAS University of London

LYNDALL STEIN – Activist/Campaigner, United Kingdom

MARC RIBOT – Musician

MARCUS DRAVS – Producer

MAREK FUCHS – MD Sauti Sol Entertainment, Kenya

MARGARET ATWOOD – Author

MARK LEVINE – Professor of History UC Irvine – Grammy winning artist

MARY GLINDON – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

MATT PENMAN – Musician, New Zealand

MARTIN GOLDSCHMIDT – Chairman, Cooking Vinyl Group

MEDARD SSEGONA – Member of Parliament, Uganda

MICHAEL CHABON – Writer

MICHAEL LEUFFEN – NTS Host, Carhartt WIP Music Rep

MICHAEL UWEDEMEDIMO – Director, CMAP and Research Fellow King’s College London

MILTON ALLIMADI – Publisher, The Black Star News

MORGAN MARGOLIS – President, Knitting Factory Entertainment, USA

MOUSTAPHA DIOP – Musician, Senegal MusikBi CEO

MR EAZI – Musician, Producer, Nigeria

MUWANGA KIVUMBI – Member of Parliament, Uganda

NAOMI WEBB – Executive Director, Good Chance Theatre, United Kingdom

NICK GOLD – Owner, World Circuit Records

NUBIAN LI – Artist, Uganda

OHAL GRIETZER – Composer

OBED CALVAIRE – Musician

OMOYELE SOWORE – Founder Sahara Reporters and Nigerian Presidential Candidate

PATRICK GRADY – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

PAUL MAHEKE – Artist, United Kingdom

PAUL MWIRU – Member of Parliament, Uganda

PETER GABRIEL – Musician

RACHEL SPENCE – Arts Writer and Poet, United Kingdom

RASHEED ARAEEN – Artist, United Kingdom

RAYMOND MUJUNI – Journalist, Uganda

RHETT MILLER – Musician, Writer

RILIWAN SALAM – Artist Manager

ROBERT MAILER ANDERSON – Writer and Producer

ROBIN DENSELOW – Journalist, United Kingdom

ROBIN EUBANKS – Trombonist, Composer, Educator

ROBIN RIMBAUD – Musician

RUTH DANIEL – CEO, In Place of War

SAMIRA BIN SHARIFU – DJ

SANDOW BIRK – Visual Artist, USA

SANDRA IZSADORE – Author, Artist, Activist, USA

SEAN JONES – Musician, Composer, Bandleader, Educator

SEBASTIAN ROCHFORD – Musician, Pola Bear

SEUN ANIKULAPO KUTI – Musician, Composer

SHAHIDUL ALAM – Photojournalist and Activist, Bangladesh

SIDNEY SULE – B.A.H.D Guys Entertainment Management, Nigeria

SIMON WOLF – Senior Associate, Amsterdam & Partners LLP

SRIRAK PLIPAT – Executive Director, Freemuse

STEPHEN BUDD – OneFest / Stephen Budd Music Ltd

SOFIA KARIM – Architect and Artist

STEPHEN HENDEL – Kalakuta Sunrise LLC

STEVE JONES – Musician and Producer

SUZANNE NOSSEL – CEO, PEN America

TANIA BRUGUERA – Artist and Activist, Cuba

TOM CAIRNES – Co-Founder Freetown Music Festival

WOLE SOYINKA – Nobel Laureate, Nigeria

YENI ANIKULAPO KUTI – Co-Executor of the Fela Anikulapo Kuti Estate

ZENA WHITE – MD, Knitting Factory and Partisan Records