2 Nov 2016 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, Russia, Ukraine

Today is the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists. Since 2006, 827 journalists have been killed for their reporting. Nine out of 10 of these cases go unpunished.

Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform verified a number of reports of impunity since it began monitoring threats to press freedom across Europe in May 2014. Here are just five reports from three countries of concern: Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.

“Impunity empowers those who orchestrate crimes and leaves victims feeling vulnerable and abandoned,” said Hannah Machlin, Index’s project officer for MMF. “What we are witnessing is a vicious cycle of unresolved crimes against journalists.”

Most recently, MMF reported that Sergey Dorovskoy, who the Lyublinski district court in Moscow recognised as orchestrating the murder of Novaya Gazeta journalist Igor Domnikov, received a 200,000 rubles (€2,860) fine but no jail time because the statute of limitations had passed. This small punishment was in compensation for “moral damages” to Domnikov’s wife.

From 1998-2000, Igor Domnikov headed Novaya Gazeta’s special projects department which ran investigations. He had published a series of articles about Dorovskoy’s alleged criminal activities and corruption.

On 19 February 2014, Vyacheslav Veremiy, a Ukrainian journalist for the newspaper, Vesti, died from injuries he sustained from a gunshot and a brutal beating. Veremiy was targeted while covering the anti-government Euromaidan protests in the country’s capital Kyiv. The two-year-old case has produced suspects but no prosecutions. The investigation remains open.

The year ended with an attack on the editor-in-chief of the news website Taiga.info, Yevgeniy Mezdrikov in Russia. Two individuals posed as couriers to gain access to the offices, where they assaulted Mezdrikov. After just one year the offender was granted a pardon.

In Ukraine, on 21 January 2015, Rivne TV journalists Arten Lahovsky and Kateryna Munkachi were physically attacked. The assailants released an unknown substance from a gas canister, choking Lahovsky. The journalists believe the attack to be premeditated and have criticised police failure to investigate.

In Belarus, officials did not file a criminal case in the assault of TUT.by journalist Pavel Dabravolski, who said he was beaten on 25 January 2016 by police while filming another incident at a court facility. The officers involved testified that Dabravolski did not present a press card when requested and grabbed at them while shouting insults. Additionally, police claimed that Dabravolski was interfering with their duties.

Dabravolski captured the incident on his mobile phone, though the recording was not considered as part of the three-month investigation into the incident. According to the journalist, he was thrown to the ground and kicked by police. He was fined for charges of contempt of court and disobeying legal demands.

Index on Censorship calls for more to be done to ensure justice is served for crimes against journalists.

6 Oct 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Magazine, Russia, Student Reading Lists, Volume 45.03 Autumn 2016 Extras

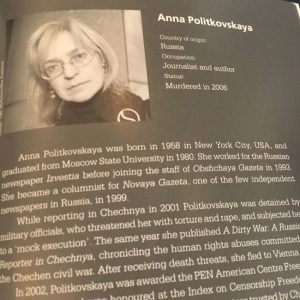

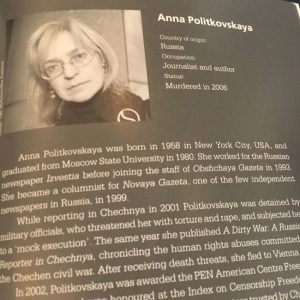

A man lays flowers near the picture of murdered journalist Anna Politkovskaya, during a rally in Moscow, Russia, 7 October 2009. CREDIT: EPA / Alamy Stock Photo

On 7 October 2006 investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya was shot and killed in her apartment building in Moscow. In the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Russian journalist Andrey Arkhangelsky reflects on Politkovskaya’s legacy 10 years on and looks at the state of journalism in the country today.

Politkovskaya, who worked for newspaper Novaya Gazetta, was known for her investigative reporting, particularly looking into the atrocities committed by Russian armed forces in Chechnya, and her criticism of the Putin administration.

She was a recipient of an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award in 2002.

Ahead of the anniversary of her death, Index has compiled a reading list of articles written for the magazine both by Politkovskaya and about her. The collection also includes articles exploring media freedom in Russia and why the deaths are Russian journalists seem to go unnoticed and uninvestigated.

From The Cadet Affair: the Disappeared; an extract, written by Anna Politkovskaya, was published in the winter 2010 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

From The Cadet Affair: the Disappeared

December 2010; vol. 39, 4: pp. 209-210.

In 2010 Index published this extract from Nothing But the Truth: Selected Dispatches, a collection of Politkovskaya’s best writings. In this piece, she writes about the disappeared in Chechnya.

Standing Alone

January 2002; vol. 31, 1: pp. 30-34.

An interview with Politkovskaya who, at the time of publication, was living in Vienna, having been sent there for her own safety by Dmitry Muratov, editor-in-chief of Noveya Gazetta, after receiving threats from high-ranking officials who had been annoyed by her reports from Chechnya.

Codes of conduct

March 2012; vol. 41, 1: pp. 85-95.

Irena Maryniak considers the hidden network of relationships that continue to shape Russian society, undermine the rule of law and protect the status quo. In this article Maryniak highlights Politkovskaya’s concerns of the effects of the Kremlin’s reach and her work reporting on the atrocities inflicted on the Chechen population by the Russian armed forces and the Russian-backed administration of Akhmad Kadyrov.

Years of Living Dangerously

November 2009; vol. 38, 4: pp. 44-58.

Grit in the engine by Robert McCrum, in the 40 year anniversary issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Maria Eismont talks to Dmitry Muratov, editor of the newspaper Novaya Gazeta, at which Politkovskaya spent seven years as a journalist, about his struggle for press freedom and justice in Russia.

Stopping the Killers

November 2009; vol. 38, 4: pp. 31-43.

In this article Joel Simon, of the Committee to Protect Journalists, discusses how impunity is an urgent issue facing press freedom campaigners; and, after reflecting on Politkovskaya’s murder, outlines a roadmap for action

The Big Squeeze

February 2008; vol. 37, 1: pp. 26-34.

Edward Lucas explains how during Putin’s presidency media freedom has moved from the imperfect to the moribund, in an adaption from his book The New Cold War: how the Kremlin menaces Russia and the West.

Grit in the engine

March 2012; vol. 41, 1: pp. 12-20.

Into the Future; Index interviews Anna Politkovskaya in the winter 2005 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Robert McCrum considers Index’s role in the history of the fight for free speech, from the oppression of the Cold War to censorship online; and highlights how Politkovskaya turned to Index for help in making the west understand the dangers Russian journalists face.

Into the Future

November 2005; vol. 34, 4: pp. 120-125.

Index interviews Politkovskaya at the Edinburgh Festival, in which she discusses the future of Russia.

“We lost journalism in Russia”

September 2015; vol. 44, 3: pp. 32-35.

Andrei Aliaksandrau examines the evolution of censorship in Russia, from Soviet institutions to today’s blend of influence and pressure.

Power of the pen

December 2010; vol. 39, 4: pp. 17-23.

Carole Seymour-Jones celebrates the achievements of 50 years of fighting for authors’ freedoms and explains why there is so much more work to be done.

You can read Andrey Arkhangelsky’s article by subscribing to the magazine or taking out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London, News from Nowhere in Liverpool and Home in Manchester; as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship to anywhere in the world.

2 Sep 2016 | Albania, Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, Kosovo, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Russia, Turkey

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

30 August 2016 – The home of veteran journalist and Index contributor Yavuz Baydar was raided by the police, the journalist reported via Twitter.

The raid came shortly after detention warrants were issued for 35 people including 27 journalists. As of 30 August, of the 27 journalists sought nine have been detained in Turkey while 18 other journalists are reportedly abroad.

Also read by Baydar: Turkey: Losing the rule of law

28 August 2016 – At around 10pm an unidentified individual threw a hand grenade at the house of Mentor Shala, the director of Kosovo’s public broadcaster RTK.

Shala and his family were inside at the time. No casualties were reported but according to the RTK director the explosion was strong and that it had shocked the whole neighbourhood.

Kosovo’s police are investigating the case, which is the second attack on national broadcaster RTK within a week. On 22 August 2016 an explosive device was thrown at the broadcaster’s headquarters.

President Hashim Thaci has condemned the attack. “Criminal attacks against media executives and their families threaten the privacy and freedom of speech, and at the same time seriously damage the image of Kosovo,” he told RTK.

Both attacks were claimed by a group called Rugovasit, which said in a written statement to RTK that the attack was “only a warning”.

Rugovasit blames RTK journalist Mentor Shala for only reporting the government’s perspective. “If he does not resign from RTK, his life is in danger,” they said.

27 August 2016 – Journalist and founder of news agency Novy Region, Alexander Shchetinin, was found dead in his apartment in Kiev.

The National Police confirmed in a statement that “a man with a gunshot wound to the head was discovered on the balcony”. He reportedly died between 8-9.30pm.

Police found cartridges, a gun and a letter at the scene. “The doors to the apartment were closed, the interior looks intact,” police reported.

“Until all the facts are established, until the examination and forensic examination is complete, we are investigating it as a murder,” said Kiev police chief Andrey Kryschenko. “The main lines of enquiry are suicide and connections with his professional activities.”

The Russian-born journalist had lived in the Ukrainian capital since 2005. He was often critical of the Russian government. In 2014, he refused Russian citizenship, later joined the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine.

20 August 2016 – Faeces was poured onto the prominent Russian journalist Yulia Latynina, who works for independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta and hosts a programme called Kod Dostupa at radio station Echo of Moscow.

According to Latynina, the incident took place close to the radio’s office at Novy Arbat in central Moscow. An unidentified individual in a motorcycle helmet perpetrated the attack, while his accomplice was waiting for him at a motorcycle nearby. The unidentified individuals fled the scene.

Latynina told Echo of Moscow that it was the 14th or the 15th time she has been attacked. She believes the assailants had been following her for a long time as they seemed to know her daily commute and where she parks her car.

Latynina also believes the incident is connected to her Novaya Gazeta investigations into billionaire Evgeny Prigozhin, who is close to Russian President Vladimir Putin. According to Latynina’s investigations, Prigozhin has orchestrated mass trolling on opposition activists in Saint Petersburg.

22 August 2016 – A prosecutor has asked for a three-month prison sentence for Faig Amirli, the director of the newspaper Azadliq, Radio Free Europe’s Azerbaijan Service.

Amirli’s lawyer declared that his client is being charged for spreading national and religious hatred, along with promoting religious sects and disturbing public order by performing religious activities.

Amirli was detained by a group of unidentified individuals on 20 August. At the time, his whereabouts were unknown while his house was searched by the representatives of Grave Crimes Unit.

Police claim they found literature related to Fethullah Gülen, the alleged orchestrator of the attempted coup in Turkey, in Amirli’s car.

His arrest is considered part of a new crackdown in Azerbaijan ahead of the September’s constitutional referendum.

Also read: Azadliq: “We are working under the dual threat of government harassment and financial insecurity”

26 Aug 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Russia, Ukraine

The conflict over Crimea and the fighting in eastern Ukraine has resulted in a media war, which has left both Russian and Ukrainian journalists struggling to report accurately on the situation, writes Mapping Media Freedom correspondent Andrey Kalikh.

In Russia, the partisan media environment has been driven by state-backed broadcasters. Federally financed TV channels — Russia 1 and RT — toe the government line on events in eastern Ukraine and Crimea. In 2015, the government boosted its funding of media to 72 billion rubles ($1.2 billion).

Mapping Media Freedom is monitoring the situation with Ukrainian media and journalists working in Russia. These are some of the cases filed by MMF Russian correspondents.

Reporting teams working for Ukrainian television outlets were barred from attending the March 2016 trial of Nadezhda Savchenko, a pilot captured by pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine and handed over to Russian military forces. Savchenko was accused of having directed artillery fire that killed two Russian journalists.

Former Los Angeles Times correspondent Sergei Loiko, a Russian, has been repeatedly harassed in Moscow, where he is based, following the publication of articles on the conflict and his book The Airport, a novel set amid the battle for Donetsk airport in eastern Ukraine. In October 2015 he received a threatening phone call, followed in April 2016 by an incident during which four unknown perpetrators approached him as he was entering independent TV Dozhd’s studio to participate in a live programme.

Some journalists have been barred from entering Russia altogether. In one case, Sergei Supinsky, an AFP photographer based in Ukraine, was stopped from traveling to Moscow from Minsk. Supinsky was told he could not board his flight. No reason was given for the ban.

Russian journalists and activists have also become targets for pressure if they are perceived as supporting Ukraine or objecting to Russian involvement in the conflict.

In April 2016, Mikhail Afanasyev, an independent Novaya Gazeta correspondent based in the Republic of Khakassia posted a photo on Facebook of Kiev’s Maidan Square, where he had recently visited. He was immediately targeted with threats and insults by people referring to themselves as “patriots”.

In December 2015, a blogger from the Siberian city of Tomsk received a five-year sentence for “extremist” videos published on his YouTube page. In one of his videos, later removed, Vadim Tyumentsev referred to refugees from eastern Ukraine “who come and stay in Tomsk, although there are enough other problems in the city”. He accused officials of providing more help to the newcomers than the local population.

This article was updated on 6 September 2016 to provide more context and clarification.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s

Each week, Index on Censorship’s