17 Jan 2025 | Asia and Pacific, News and features, Vietnam, Volume 53.04 Winter 2024

This article first appeared in Volume 53, Issue 4 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Unsung Heroes: How musicians are raising their voices against oppression. Read more about the issue here. The issue was published on 12 December 2024.

Hoàng Minh Tường has published 17 novels. Seven of these have been banned from re-publication or circulation in Vietnam and two had to be published overseas due to political sensitivities. But the Hanoi-based writer remains upbeat.

“I have been blessed by the heavenly gods,” said the 76-year-old, who used to work as a teacher and journalist. “Many times, I was afraid that I might be imprisoned. Yet I still remain alive.”

The award-winning novelist is currently seeking help to have his best- known novel Thời của Thánh Thần (The Time of the Gods) translated into English. On release in 2008, it was widely regarded as a literary phenomenon yet was immediately recalled and has been banned ever since.

Hoàng, and many other writers I spoke to for this article, agreed that censorship is accepted as part of living and working in Vietnam, where the Communist Party monopolises the publishing industry. The 2012 Publishing Law emphasises the need to “fight against all thoughts and behaviour detrimental to the national interests and contribute to the construction and defence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam”.

But censorship of fiction is just one part of the country’s free expression quandary. Reporters Without Borders has long categorised Vietnam as being among the worst countries for freedom of the press. The Ministry of Information and Communications (MIC) is the government agency responsible for state management of press, publishing and printing activities. Writers have to regularly negotiate with censors – and then creatively rise above them or patiently wait for the individuals or agencies in charge to change their minds.

Living with censorship

Hoàng, a Communist Party member, said that The Time of the Gods, written between 2005 and 2008, was a turning point in his literary career, which has spanned three decades.

“After finishing writing the book in 2008, my biggest concern was how to get it published,” he said. “I gave it to three influential friends in three publishing houses, all of whom rejected it because if they published it they would be sent to jail.”

In his banned novel, the characters are multi-faceted. Four brothers navigate different sides of armed conflicts, align with various factions and transcend the simplistic “us versus the enemy” narrative often depicted by the Communist Party.

They endure many of the hidden, historical tribulations of Vietnam – from the Maoist land reform in the 1950s, which seized agricultural land and property owned by landlords for redistribution, to the fall of Saigon in 1975, which ended the Vietnam War and resulted in a mass exodus to escape the victorious communist regime.

“The story of a family is not just the story of a single family but the story of the times, the story of the nation, the story of the two communist and capitalist factions, of the North and South regions of Vietnam and the United States,” said Hoàng. “Perhaps that is why, for the past 15 years, tens of thousands of illegal copies of the book have been printed and people still seek it out to read.”

The ban has created fertile ground for black market circulation, he said, with online and offline pirated copies often full of mistakes. There have never been any official government documents justifying the book ban, nor has there been any explanation for the sensitivities surrounding his works. He asserted that this lack of transparency and accountability was a common occurrence for novelists. “Most of the bans [on my books] were purely by word of mouth,” he said.

For years, Hoàng has communicated with editors at the state-owned Writers’ Association Publishing House (which originally published the book), but to no avail. However, the novel has made its way to global audiences, being translated into Korean, French, Japanese and Mandarin Chinese.

His 2014 novel Nguyên khí (Vitality) was originally rejected for publication, and again reasons were not disclosed. The story, revolving around Nguyễn Trãi – a 15th century historical figure who was a loyal and skilled official falsely accused of killing an emperor – symbolises the still strained relationship between single-party rule and patriotic intellectuals. In response, Hoàng revised the narrative of the novel by getting rid of a character – a security agent doubling as a censor and eavesdropper. He retitled the work to The Tragedy of a Great Character, a rebranding that managed to pass through pre-print censorship. Subsequently, in 2019, the book was published and sold out. However, its previous ban was soon recognised, so it didn’t secure a permit for republication.

Learning from history

In his 2022 article Banishing the Poets: Reflections on Free Speech and Literary Censorship in Vietnam, Richard Quang Anh Trần, assistant professor of Southeast Asian studies at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, concluded that the literary landscape in Vietnam was “as limited as political speech itself”.

“The boundaries of permissible speech, moreover, are ever changing that one may find oneself caught in the crosshairs and on the wrong side at any given moment,” he wrote.

Trần identified two turning points when writers were fooled into believing that the Communist Party had allowed them to challenge the established literary norms of serving the party. The first occurred in the 1950s, during a cultural-political movement in Hanoi, called the Nhân Văn-Giai Phẩm Affair. A group of party-loyal writers and intellectuals launched two journals, Nhân Văn (Humanity) and Giai Phẩm (Masterpieces). They sought to convince the party of the need for greater artistic and intellectual freedom. Despite their distinguished service to the state, they were condemned in state media and their publications were banned.

The second case came in the late 1980s and early 1990s during Doi Moi (the Renovation Period), a series of economic and political reforms which started in 1986. Vietnam’s market liberalisation breathed new life into war-centric literature, and many writers crafted brilliant post-war novels that challenged prevailing narratives – but their works were censored. This was done through limiting the number of approved copies, recalling and confiscating books from libraries and bookshops, and destroying original drafts.

Censorship was at its worst when the party decided to burn the books of those it regarded as its enemies. Following the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975, it embarked on a campaign to eliminate what it classified as decadent and reactionary culture, including many books and magazines published in the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam).

“South Vietnamese publications were the main target, plus much of popular music, movies and the fine arts,” said Dr Tuấn Hoàng, associate professor of great books at Pepperdine University’s Seaver College in California. “Government workers entered businesses and private residences suspected of having such materials and took away what they could find.”

“Those materials were burned or recycled at factories,” he said. “Citizens were urged to give up banned materials to the government, or to destroy them themselves. A lot of materials were therefore destroyed in the first few years after the war.”

But some materials were hidden, circulated clandestinely or sold on the black market. Phạm Thị Hoài is one of the most celebrated writers of the post- Renovation Period, whose debut novel The Crystal Messenger was a success both at home and abroad. The first edition (1988) and second edition (1995) were published by the Writers’ Association Publishing House, bar a few censored paragraphs, according to Phạm. But it was later banned by the government.

After leaving Vietnam for Germany, in 2001 she established Talawas, an online forum dedicated to reviving literary works by Vietnamese writers. She says she has been banned from travelling back to her home country since 2004, a fact she attributes to Talawas and her literary works, which have been ambiguously deemed to be “sensitive”. Her books have not been permitted to be republished in Vietnam.

“A few years ago, a friend in the publishing industry also tried to inquire about reprinting a collection of my short stories, which were entirely about love, but no publishing house accepted it,” she said.

In 2018, the government introduced a new cybersecurity law, which has made censorship worse. Critical voices that challenge the state’s version of history online are deemed to be hostile forces that are seeking to discredit the party’s revolutionary achievements.

Appreciate, don’t criticise

Censorship also makes its way into education as, in Vietnam, literature is first and foremost intended to inculcate party- defined patriotism into young minds.

According to Dr Ngọc, a high-school literature teacher in Hanoi, Vietnamese authors who are featured in school textbooks normally have very “red” (communist) backgrounds or hold party leadership positions. She added that the higher an author’s position in government, the more focus is given to their work in textbooks. “Many great writers were unfortunately not selected for the literature textbooks,” she said.

Ngọc provides tutoring for high- school students to help them prepare for their national entrance exams. These exams mostly focus on wartime hardship and heroism. Students’ responses need to show that they revere communist leaders and revile invaders. But this teaching method is not best placed to help them appreciate literature.

But ill-fated books still find their way to readers, often through the black market. Phương (not her real name) has been selling books in Hanoi for the past two decades. She says that every now and then people still look for banned books, which she collects and sells. However, these are reserved only for her closest customers.

“I would not sell sensitive books to a random buyer,” she said. “They might be disguised security agents trying to recall the book from the market.”

21 Jan 2019 | Global Journalist, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Vietnam

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published interviews with exiled journalists from around the world.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”104715″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Dang Xuan Dieu has paid a heavy price for resisting the Vietnamese government.

A community activist, blogger and frequent contributor to the Catholic news outlet Vietnam Redemptorist News, a site that often reports on human rights violations, Dieu was arrested in July 2011 and charged with attempting to overthrow the Southeast Asian nation’s Communist government. He was held without trial until January 2013, when he and 13 other writers and human rights activists were convicted after a two-day trial in the central city of Vinh.

Dieu was sentenced to 13 years in prison and five years of house arrest under Article 79 of the country’s penal code, which criminalises activities aimed at overthrowing the government. He was also accused of being a member being of Viet Tan, an exile-run political party banned in the country.

Such trials aren’t unusual in Vietnam. The Communist Party maintains near-total control over Vietnam’s judiciary, media and civil society. Internet in the country is heavily censored, and nearly 100 political prisoners are behind bars, according to Amnesty International.

Expressing dissent in Vietnamese prisons is even harder. The country’s Communist government often seeks to pressure inmates into confessing to alleged crimes in prison, and if they refuse, they can be beaten or tortured.

Yet resist is what Dieu did. He refused to confess, refused to wear a prison uniform and periodically went on hunger strikes to protest his detention and the treatment of prisoners.

“In Vietnam, a lot of people are arrested where they are harassed and tortured, which forces many people to confess their crimes,” says Dieu, 39, in an interview with Global Journalist. “I never accepted the charges and chose to not admit to any guilt. Because of this, I was unable to see my lawyer or my family.”

In his six years in prison, Dieu endured extensive torture and harassment. He was severely beaten for refusing to wear the prison uniform, and was held in solitary confinement for extensive periods in what he described as a “tiny room with no room to breathe.” According to Amnesty International, he was also shackled in a cell with another prisoner who beat him, forced to drink unclean water, denied access to water for bathing and was forced to live in unsanitary conditions without a toilet.

In early January 2017, as U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry travelled to Vietnam, Dieu was granted early release on the condition that he immediately leave the country. Now living in France, Dieu is a student and continues to blog about Vietnam. Through a translator, he spoke with Global Journalist’s Shirley Tay about the abuse he faced in prison and the country’s media climate. Below, an edited version of their interview:

Global Journalist: How did you get into journalism?

Dang Xuan Dieu: I was a student and contributor to the Vietnam Redemptorist News, and I would write about social justice issues. I created my own blog, Tâm và Tầm [Mind and Games] and also worked with a news website Dang Luon.

[Vietnam] restricts independent media and control all media outlets to maintain power. All media is monitored by the Communist Party of Vietnam, so state bodies end up creating their own media or newspapers. There are probably 600 media outlets in Vietnam at the moment, but all are currently controlled by the government. When I was active in 2011, writing blogs and independent news articles was actually quite dangerous.

GJ: What were some of the work that got you into trouble?

Dieu: While I am Catholic, I also work on other forms of activism. The Vietnamese government often tries to control the information that people are able to have. So I created a small, independent organisation to promote education on things like safe sex, pregnancy, and other issues that youth face. Because it was an independent group, we were often targeted. We were asked to go to the police station several times when we were organising in various parishes.

During this time, I started connecting with civil rights activists from overseas who taught me how to manage and organise independent civil society organisations. After that, I travelled overseas to attend some of these classes. On the way back to Vietnam, I was charged for attending a class on leadership training and nonviolent struggle.

GJ: Can you tell me about your time in prison?

Dieu: In prisons, they have their own systems to punish prisoners. There are areas that allow for people to move freely and do normal, day-to-day activities, but there are also areas within the normal prison that are like a prison within a prison within a prison. So I was in what you would call a third-degree prison area, where people are primarily shackled and kept in solitary confinement.

The problems started when I did not confess to any crimes and when I refused to wear the prison uniform because I believed I wasn’t guilty. I was placed in a cell with someone who was charged for murder and who tried to [beat me] to force me to wear the prison uniform and confess to crimes. He may have been doing this on orders from various prison officials.

After that person was transferred, I started advocating for the rights of prisoners, such as writing petitions to officers regarding mistreatment. As a Catholic, I wasn’t allowed to practice my faith or read the Bible. There were several other injustices which led me to begin a hunger strike.

As punishment, they placed me in solitary confinement. The majority of my six years in prison was in solitary confinement or in cells with very dangerous people as cellmates. During my time in prison, they saw me as a resister and so they didn’t allow me to see my family at any time.

What was worse was that they actually told my family that I refused to see them, rather than that I wasn’t allowed to see them. Because of this, I held an extended hunger strike where I ate only one meal a day for nearly a year, and this led to a transfer of prison locations.

GJ: How did you manage to get out of prison?

Dieu: There was another prison inmate who lived close to my cell, where I had been tortured and mistreated. When he was released, he actually told the wider community about what was going on in prison. At that time, the prison wasn’t able to block information going in and out of the prison.

So the community started organising campaigns calling for my release, and there were diplomats from the European Union, France, the U.S., Australia and Sweden who visited me. At that time, the EU diplomat asked if I wanted to be exiled to a country in Europe. I refused because I wanted to advocate for the release of other people, not my own release.

After the diplomat’s visit, they took me to a different cell and then never allowed me to leave that area for about six months. The situation started becoming dangerous to my life and luckily, another inmate who was not a political prisoner, but just a regular prisoner, was released and contacted my family to inform them of my prison conditions.

So the EU and a French diplomat visited me again, this was during the time of French President [François] Hollande’s visit to Vietnam in September 2016. My family was able to pass me a letter asking me to go into exile. Upon receiving that letter, I agreed. After that, it took another three months for them to arrange it.

GJ: At that point, were you ready to go in to exile?

It was only the letter from my mother which pushed me to choose to be exiled. It was because my mother is fairly old now, and she wanted to see me released before she died. I was determined, I was willing to die in prison rather than be exiled. The Vietnamese government tries to push activists outside of Vietnam, because they see that it’s not a win for activism. And obviously, for humanitarian reasons, a lot of the community advocates for the release of these prisoners.

GJ: Do you have plans to return?

Dieu: I want to return to Vietnam, but it depends on there being changes through international pressure. If I were to return now, I would definitely be arrested. I will just have to wait.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/6BIZ7b0m-08″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook). We’ll send you our weekly newsletter, our monthly events update and periodic updates about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share, sell or transfer your personal information to anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

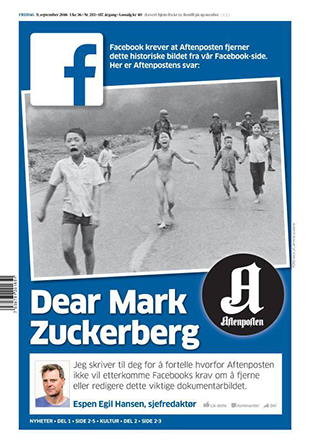

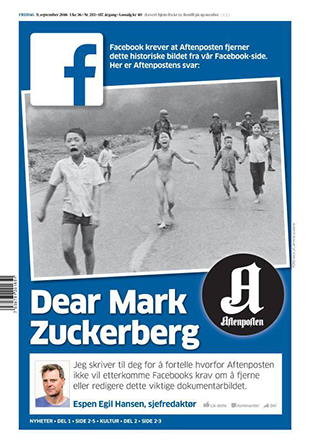

9 Sep 2016 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Norway, Statements

Index on Censorship, a global organisation that campaigns for free expression, fully supports the action of Norway’s Aftenposten newspaper in refusing a request from Facebook to remove an iconic photo of the Vietnam War that features a naked child running from a napalm attack.

Index on Censorship, a global organisation that campaigns for free expression, fully supports the action of Norway’s Aftenposten newspaper in refusing a request from Facebook to remove an iconic photo of the Vietnam War that features a naked child running from a napalm attack.

The social media platform later reversed its decision.

Aftenposten, Norway’s largest newspaper by circulation, said in a front-page editorial on 9 September that Facebook emailed the newspaper to demand the removal of a documentary photograph from the Vietnam War made by Nick Ut of The Associated Press. “Less than 24 hours after the email was sent, and before I had time to give my response, you intervened yourselves and deleted the article as well as the image from Aftenposten’s Facebook page,” Aftenposten’s editor in chief said in the editorial, written as a letter to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

Index is shocked and disturbed by the behaviour of Facebook in this matter. We understand that Facebook, as a private company, has the right to impose terms of service as it sees fit and this includes policies with which we may not agree – such as its policies on nudity. However, its actions in this case demonstrate the crucial role that context plays in assessing what content should be removed. As Aftenposten editor Espen Egil Hansen writes: Facebook rules “don’t distinguish between child pornography and famous war photos”.

Furthermore, Facebook’s decision undermines media freedom by removing from an independent media outlet’s own page an image and article that that organisation has made the considered decision to publish. This calls into question the entire model of Facebook as a social media platform. If Index, for example, is not able to freely publish articles on our own Facebook page that we feel to be important, what purpose is there for us to use Facebook at all? Facebook ceases in this scenario to be a champion, or even a conduit, of free speech.

Finally, Facebook should be a platform for debate. We understand from Aftenposten that when Norwegian author Tom Egeland challenged a decision by Facebook to remove the picture of Phan Thi Kim Phuc from a post he made, he was excluded from Facebook. This, again, flies in the face of the notion that Facebook is a platform for open debate.

Open debate, including the viewing of images and stories that some people may find offensive, is vital for democracy. Platforms such as Facebook can play an essential role in ensuring this. We urge Facebook not just to overturn this decision but to renew its commitment to providing a platform that allows for public debate. This means supporting the free sharing of legal information no matter how offensive it may appear to others.

Index on Censorship, a global organisation that campaigns for free expression, fully supports the action of Norway’s Aftenposten newspaper in refusing a request from Facebook to remove an iconic photo of the Vietnam War that features a naked child running from a napalm attack.

Index on Censorship, a global organisation that campaigns for free expression, fully supports the action of Norway’s Aftenposten newspaper in refusing a request from Facebook to remove an iconic photo of the Vietnam War that features a naked child running from a napalm attack.