11 Feb 2017 | Index in the Press

Eaten Fish (Ali Dorani), a 25-year-old Iranian cartoonist began a hunger strike on January 31 in Manus Island detention centre. He has now been on hunger strike for more than two weeks. The Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA) published an open letter on February 5 calling on the federal government to free and resettle Eaten Fish and two other media colleagues, journalist Behrouz Boochani and actor Mehdi Savari. Read the full article

7 Feb 2017 | Americas, Art and the Law, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Today, more than thirty cultural institutions and human rights organisations around the world, including international arts, curators’ and critics’ associations, organisations protecting free speech rights, as well as US based performance, arts and creative freedom organisations and alliances, issued a joint statement opposing United States President Donald J. Trump’s immigration ban. Read the full statement below.

On Friday, January 27th, President Trump signed an Executive Order to temporarily block citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries from entering the United States. This order bars citizens of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen from entering the United States for 90 days. It also suspends the entry of all refugees for 120 days and bars Syrian refugees indefinitely.

The organisations express grave concern that the Executive Order will have a broad and far-reaching impact on artists’ freedom of movement and, as a result, will seriously inhibit creative freedom, collaboration, and the free flow of ideas. US border regulations, the organisations argue, must only be issued after a process of deliberation which takes into account the impact such regulations would have on the core values of the country, on its cultural leadership, and on the world as a whole.

Representatives of several of the participating organisations issued additional statements on the immigration ban and its impact on writers and artists:

Helge Lunde, Executive Director of ICORN, said, “Freedom of movement is a fundamental right. Curtailing this puts vulnerable people, people at risk and those who speak out against dictators and aggressors, at an even greater risk.”

Svetlana Mintcheva, Director of Programs at the US National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC), said, “In a troubled and divided world, we need more understanding, not greater divisions. It is the voices of artists that help us understand, empathise, and see the common humanity underlying the separations of political and religious differences. Silencing these voices is not likely to make us any safer.”

Suzanne Nossel, Executive Director of PEN America, said, “The immigration ban is interfering with the ability of artists and creators to pursue their work and exercise their right to free expression. In keeping with its mission to defend open expression and foster the free flow of ideas between cultures and across borders, PEN America vows to fight on behalf of the artists affected by this Executive Order.”

Diana Ramarohetra, Project Manager of Arterial Network, said, “A limit on mobility and limits on freedom of expression has the reverse effect – to spur hate and ignorance. Artists from Somalia and Sudan play a crucial role in spreading the message to their peers about human rights, often putting themselves at great risk in countries affected by ongoing conflict. Denying them safety is to fail them in our obligation to protect and defend their rights.”

Ole Reitov, Executive Director of Freemuse, said, “This is a de-facto cultural boycott, not only preventing great artists from performing, but even negatively affecting the US cultural economy and its citizens rights to access important diversity of artistic expressions.”

Shawn Van Sluys, Director of Musagetes and ArtsEverywhere, said, “Musagetes/ArtsEverywhere stands in solidarity with all who protect artist rights and the freedom of mobility. It is time for bold collective actions to defend free and open inquiry around the world.”

A growing number of organisations continue to sign the statement.

JOINT STATEMENT REGARDING THE IMPACT OF THE US IMMIGRATION BAN ON ARTISTIC FREEDOM

Freedom of artistic expression is fundamental to a free and open society. Uninhibited creative expression catalyses social and political engagement, stimulates the exchange of ideas and opinions, and encourages cross-cultural understanding. It fosters empathy between individuals and communities, and challenges us to confront difficult realities with compassion.

Restricting creative freedom and the free flow of ideas strikes at the heart of the core values of an open society. By inhibiting artists’ ability to move freely in the performance, exhibition, or distribution of their work, United States President Trump’s January 27 Executive Order, blocking immigration from seven countries to the United States and refusing entry to all refugees, jettisons voices which contribute to the vibrancy, quality, and diversity of US cultural wealth and promote global understanding.

The Executive Order threatens the United States safe havens for artists who are at risk in their home countries, in many cases for daring to challenge repressive regimes. It will deprive those artists of crucial platforms for expression and thus deprive all of us of our best hopes for creating mutual understanding in a divided world. It will also damage global cultural economies, including the cultural economy of the United States.

Art has the power to transcend historical divisions and socio-cultural differences. It conveys essential, alternative perspectives on the world. The voices of cultural workers coming from every part of the world – writers, visual artists, musicians, filmmakers, and performers – are more vital than ever today, at a time when we must listen to others in the search for unity and global understanding, when we need, more than anything else, to imagine creative solutions to the crises of our time.

As cultural or human rights organisations, we urge the United States government to take into consideration all these serious concerns and to adopt any regulations of United States borders only after a process of deliberation, which takes into account the impact such regulations would have on the core values of the country, on its cultural leadership, as well as on the world as a whole.

African Arts Institute (South Africa)

Aide aux Musiques Innovatrices (AMI) (France)

Alliance for Inclusion in the Arts (USA)

Arterial (Africa)

Artistic Freedom Initiative (USA)

ArtsEverywhere (Canada)

Association of Art Museum Curators and Association of Art Museum Curators Foundation

Association Racines (Morocco)

Bamboo Curtain Studio (Taiwan)

Cartoonists Rights Network International

Cedilla & Co. (USA)

Culture Resource – Al Mawred Al Thaqafy (Lebanon)

International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art (CIMAM)

College Art Association (USA)

European Composer and Songwriter Alliance (ECSA)

European Council of Artists

Freemuse: Freedom of Expression for Musicians

Index on Censorship: Defending Free Expression Worldwide

Independent Curators International

International Arts Critics Association

International Network for Contemporary Performing Arts

The International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN)

Levy Delval Gallery (Belgium)

Geneva Ethnography Museum (Switzerland)

National Coalition Against Censorship (USA)

New School for Drama Arts Integrity Initiative (USA)

Observatoire de la Liberté de Création (France)

On the Move | Cultural Mobility Information Network

PEN America (USA)

Queens Museum (USA)

Roberto Cimetta Fund

San Francisco Art Institute (USA)

Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDC) (USA)

Tamizdat (USA)

Vera List Center for Art and Politics, New School (USA)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1486570424977-7a30af48-045a-3″ taxonomies=”3784″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Feb 2017 | Awards, News, Press Releases

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

- Sixteen courageous individuals and organisations who fight for freedom of expression in every part of the world

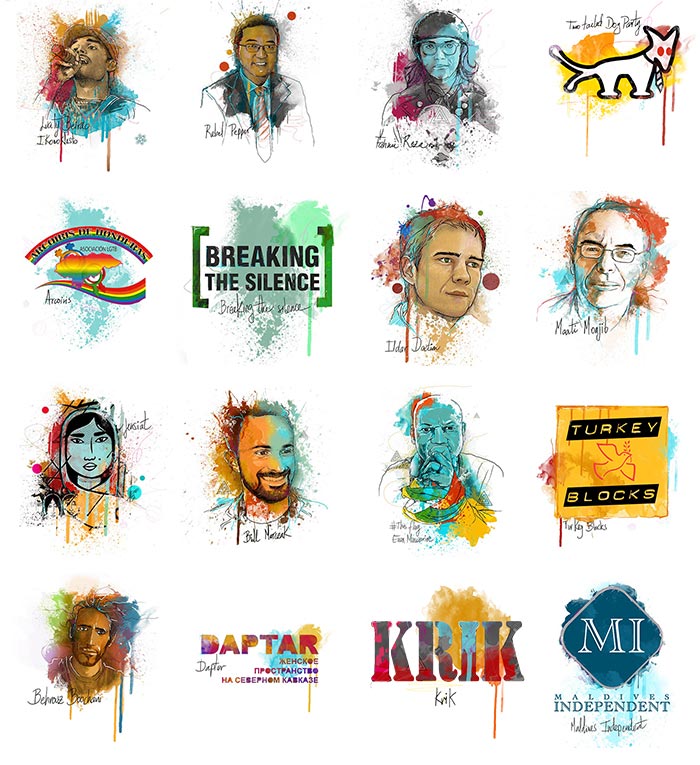

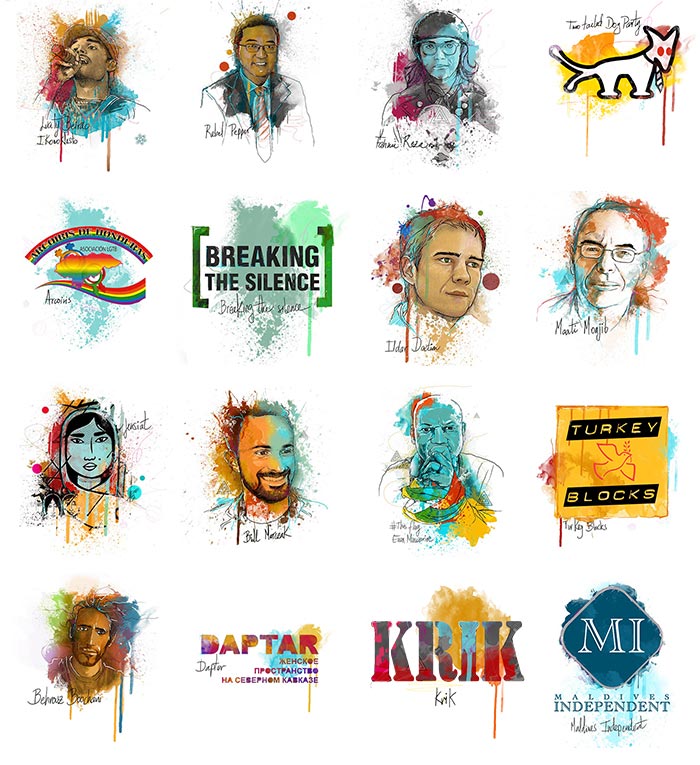

A Zimbabwean pastor who was arrested by authorities last week for his #ThisFlag campaign, an Iranian Kurdish journalist covering his life as an interned Australian asylum seeker, one of China’s most notorious political cartoonists, and an imprisoned Russian human rights activist are among those shortlisted for the 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards.

Drawn from more than 400 crowdsourced nominations, the shortlist celebrates artists, writers, journalists and campaigners overcoming censorship and fighting for freedom of expression against immense obstacles. Many of the 16 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution or exile.

“The creativity and bravery of the shortlist nominees in challenging restrictions on freedom of expression reminds us that a small act — from a picture to a poem — can have a big impact. Our nominees have faced severe penalties for standing up for their beliefs. These awards recognise their courage and commitment to free speech,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of campaigning nonprofit Index on Censorship.

Awards are offered in four categories: arts, campaigning, digital activism and journalism.

Nominees include Pastor Evan Mawarire whose frustration with Zimbabwe’s government led him to the #ThisFlag campaign; Behrouz Boochani, an Iranian Kurdish journalist who documents the life of indefinitely-interned Australian asylum seekers in Papua New Guinea; China’s Wang Liming, better known as Rebel Pepper, a political cartoonist who lampoons the country’s leaders; Ildar Dadin, an imprisoned Russian opposition activist, who became the first person convicted under the country’s public assembly law; Daptar, a Dagestani initiative tackling women’s issues like female genital mutilation that are rarely discussed publicly in the country; and Serbia’s Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK), which was founded by a group of journalists to combat pervasive corruption and organised crime.

Other nominees include Hungary’s Two-tail Dog Party, a group of satirists who parody the country’s political discourse; Honduran LGBT rights organisation Arcoiris, which has had six activists murdered in the past year for providing support to the LGBT community and lobbying the country’s government; Luaty Beirão, a rapper from Angola, who uses his music to unmask the country’s political corruption; and Maldives Independent, a website involved in revealing endemic corruption at the highest levels in the country despite repeated intimidation.

Judges for this year’s awards, now in its 17th year, are Harry Potter actor Noma Dumezweni, Hillsborough lawyer Caiolfhionn Gallagher, former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown, designer Anab Jain and music producer Stephen Budd.

Dumezweni, who plays Hermione in the stage play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, was shortlisted earlier this year for an Evening Standard Theatre Award for Best Actress. Speaking about the importance of the Index Awards she said: “Freedom of expression is essential to help challenge our perception of the world”.

Winners, who will be announced at a gala ceremony in London on 19 April, become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given support for their work, including training in areas such as advocacy and communications.

“The GreatFire team works anonymously and independently but after we were awarded a fellowship from Index it felt like we had real world colleagues. Index helped us make improvements to our overall operations, consulted with us on strategy and were always there for us, through the good times and the pain,” Charlie Smith of GreatFire, 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards Digital Activism Fellow.

This year, the Freedom of Expression Awards are being supported by sponsors including SAGE Publishing, Google, Vodafone, media partner CNN, VICE News, Doughty Street Chambers, Psiphon and Gorkana. Illustrations of the nominees were created by Sebastián Bravo Guerrero.

Notes for editors:

- Index on Censorship is a UK-based non-profit organisation that publishes work by censored writers and artists and campaigns against censorship worldwide.

- More detail about each of the nominees is included below.

- The winners will be announced at a ceremony at The Unicorn Theatre, London, on 19 April.

For more information, or to arrange interviews with any of those shortlisted, please contact: Sean Gallagher on 0207 963 7262 or [email protected]. More biographical information and illustrations of the nominees are available at indexoncensorship.org/indexawards2017.

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards nominees 2017

Arts

Luaty Beirão, Angola

Rapper Luaty Beirão, also known as Ikonoklasta, has been instrumental in showing the world the hidden face of Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos’s rule. For his activism Beirão has been beaten up, had drugs planted on him and, in June 2015, was arrested alongside 14 other people planning to attend a meeting to discuss a book on non-violent resistance. Since being released in 2016, Beirão has been undeterred attempting to stage concerts that the authorities have refused to license and publishing a book about his captivity entitled “I Was Freer Then”, claiming “I would rather be in jail than in a state of fake freedom where I have to self-censor”.

Rebel Pepper, China

Wang Liming, better known under the pseudonym Rebel Pepper, is one of China’s most notorious political cartoonists. For satirising Chinese Premier Xi Jinping and lampooning the ruling Communist Party, Rebel Pepper has been repeatedly persecuted. In 2014, he was forced to remain in Japan, where he was on holiday, after serious threats against him were posted on government-sanctioned forums. The Chinese state has since disconnected him from his fan base by repeatedly deleting his social media accounts, he alleges his conversations with friends and family are under state surveillance, and self-imposed exile has made him isolated, bringing significant financial struggles. Nonetheless, Rebel Pepper keeps drawing, ferociously criticising the Chinese regime.

Fahmi Reza, Malaysia

On 30 January 2016, Malaysian graphic designer Fahmi Reza posted an image online of Prime Minister Najib Razak in evil clown make-up. From T-shirts to protest placards, and graffiti on streets to a sizeable public sticker campaign, the image and its accompanying anti-sedition law slogan #KitaSemuaPenghasut (“we are all seditious”) rapidly evolved into a powerful symbol of resistance against a government seen as increasingly corrupt and authoritarian. Despite the authorities’ attempts to silence Reza, who was banned from travel and has since been detained and charged on two separate counts under Malaysia’s Communications and Multimedia Act, he has refused to back down.

Two-tailed Dog Party, Hungary

A group of satirists and pranksters who parody political discourse in Hungary with artistic stunts and creative campaigns, the Two-tailed Dog Party have become a vital alternative voice following the rise of the national conservative government led by Viktor Orban. When Orban introduced a national consultation on immigration and terrorism in 2015, and plastered cities with anti-immigrant billboards, the party launched their own mock questionnaires and a popular satirical billboard campaign denouncing the government’s fear-mongering tactics. Relentlessly attempting to reinvigorate public debate and draw attention to under-covered or taboo topics, the party’s efforts include recently painting broken pavement to draw attention to a lack of public funding.

Campaigning

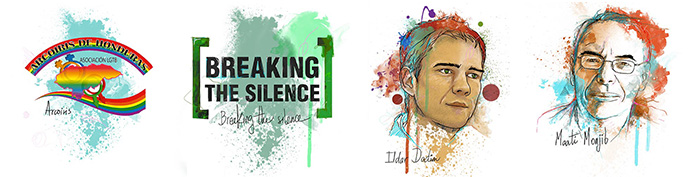

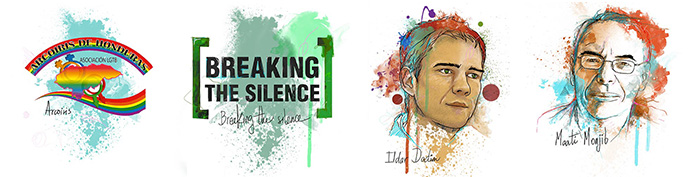

Arcoiris, Honduras

Arcoiris, Honduras

Established in 2003, LGBT organisation Arcoiris, meaning ‘rainbow’, works on all levels of Honduran society to advance LGBT rights. Honduras has seen an explosion in levels of homophobic violence since a military coup in 2009. Working against this tide, Arcoiris provide support to LGBT victims of violence, run awareness initiatives, promote HIV prevention programmes and directly lobby the Honduran government and police force. From public marches to alternative awards ceremonies, their tactics are diverse and often inventive. Between June 2015 and March 2016, six members of Arcoiris were killed for this work. Many others have faced intimidation, harassment and physical attacks. Some have had to leave the country because of threats they were receiving.

Breaking the Silence, Israel

Breaking the Silence, an Israeli organisation consisting of ex-Israeli military conscripts, aims to collect and share testimonies about the realities of military operations in the Occupied Territories. Since 2004, the group has collected over 1,000 (mainly anonymous) statements from Israelis who have served their military duty in the West Bank and Gaza. For publishing these frank accounts the organisation has repeatedly come under fire from the Israeli government. In 2016 the pressure on the organisation became particularly pointed and personal, with state-sponsored legal challenges, denunciations from the Israeli cabinet, physical attacks on staff members and damages to property. Led by Israeli politicians including the prime minister, and defence minister, there have been persistent attempts to force the organisation to identify a soldier whose anonymous testimony was part of a publication raising suspicions of war crimes in Gaza. Losing the case would set a precedent that would make it almost impossible for Breaking the Silence to operate in the future. The government has also recently enacted a law that would bar the organisation’s widely acclaimed high school education programme.

Ildar Dadin, Russia

A long-term opposition and LGBT rights activist, Ildar Dadin was the first, and remains the only, person to be convicted under Russia’s 2014 public assembly law that prohibits the “repeated violation of the order of organising or holding meetings, rallies, demonstrations, marches or picketing”. Attempting to circumvent this restrictive law, Dadin held a series of one-man pickets against human rights abuses – an enterprise for which he was arrested and sentenced to three years imprisonment in 2015. In November 2016, website Meduza published a letter smuggled to his wife in which Dadin wrote that he was being tortured and abuse was endemic in Russian jails. The letter, a brave move for a serving prisoner, had wide resonance, prompting a reaction from the government and an investigation. Against his will, Dadin was transferred and disappeared within the Russian prison system until a wave of public protest led to his location being revealed in January 2017. Dadin was released on February 26 after a supreme court order.

Maati Monjib, Morocco

A well-known academic who teaches African studies and political history at the University of Rabat since returning from exile, Maati Monjib co-founded Freedom Now, a coalition of Moroccan human rights defenders who seek to promote the rights of Moroccan activists and journalists in a country ranked 131 out of 180 on the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. His work campaigning for press freedom – including teaching investigative journalism workshops and using of a smartphone app called Story Maker designed to support citizen journalism – has made him a target for the authorities who insist that this work is the exclusive domain of state police. For his persistent efforts, Monjib is currently on trial for “undermining state security” and “receiving foreign funds.”

Digital Activism

Jensiat, Iran

Jensiat, Iran

Despite growing public knowledge of global digital surveillance capabilities and practices, it has often proved hard to attract mainstream public interest in the issue. This continues to be the case in Iran where even with widespread VPN usage, there is little real awareness of digital security threats. With public sexual health awareness equally low, the three people behind Jensiat, an online graphic novel, saw an an opportunity to marry these challenges. Dealing with issues linked to sexuality and cyber security in a way that any Iranian can easily relate to, the webcomic also offers direct access to verified digital security resources. Launched in March 2016, Jensiat has had around 1.2 million unique readers and was rapidly censored by the Iranian government.

Bill Marczak, United States

A schoolboy resident of Bahrain and PhD candidate in computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, Bill Marczak co-founded Bahrain Watch in 2013. Seeking to promote effective, accountable and transparent governance, Bahrain Watch works by launching investigations and running campaigns in direct response to social media posts coming from activists on the front line. In this context, Marczak’s personal research has proved highly effective, often identifying new surveillance technologies and targeting new types of information controls that governments are employing to exert control online, both in Bahrain and across the region. In 2016 Marczak investigated several government attempts to track dissidents and journalists, notably identifying a previously unknown weakness in iPhones that had global ramifications.

#ThisFlag and Evan Mawarire, Zimbabwe

In May 2016, Baptist pastor Evan Mawarire unwittingly began the most important protest movement in Zimbabwe’s recent history when he posted a video of himself draped in the Zimbabwean flag, expressing his frustration at the state of the nation. A subsequent series of YouTube videos and the hashtag Mawarire used, #ThisFlag, went viral, sparking protests and a boycott called by Mawarire, which he estimates was attended by over eight million people. A scale of public protest previously inconceivable, the impact was so strong that private possession of Zimbabwe’s national flag has since been banned. The pastor temporarily left the country following death threats and was arrested in early February as he returned to his homeland.

Turkey Blocks, Turkey

In a country marked by increasing authoritarianism, a strident crackdown on press and social media as well as numerous human rights violations, Turkish-British technologist Alp Toker brought together a small team to investigate internet restrictions. Using Raspberry Pi technology they built an open source tool able to reliably monitor and report both internet shut downs and power blackouts in real time. Using their tool, Turkey Blocks have since broken news of 14 mass-censorship incidents during several politically significant events in 2016. The tool has proved so successful that it has begun to be implemented elsewhere globally.

Journalism

Behrouz Boochani, Manus Island, Papua New Guinea/Australia (he is an Iranian refugee)

Iranian Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani fled the city of Ilam in Iran in May 2013 after the police raided the Kurdish cultural heritage magazine he had co-founded, arresting 11 of his colleagues. He travelled to Australia by boat, intending to claim asylum, but less than a month after arriving he was forcibly relocated to a “refugee processing centre” in Papua New Guinea that had been newly opened. Imprisoned alongside nearly 1000 men who have been ordered to claim asylum in Papua New Guinea or return home, Boochani has been passionately documenting their life in detention ever since. Publicly advertised by the Australian Government as a refugee deterrent, life in the detention centre is harsh. For the first 2 years, Boochani wrote under a pseudonym. Until 2016 he circumvented a ban on mobile phones by trading personal items including his shoes with local residents. And while outside journalists are barred, Boochani has refused to be silent, writing numerous stories via Whatsapp and even shooting a feature film with his phone.

Daptar, Dagestan, Russia

In a Russian republic marked by a clash between the rule of law, the weight of traditions, and the growing influence of Islamic fundamentalism, Daptar, a website run by journalists Zakir Magomedov and Svetlana Anokhina, writes about issues affecting women, which are little reported on by other local media. Meaning “diary”, Daptar seeks to promote debate and in 2016 they ran a landmark story about female genital mutilation in Dagestan, which broke the silence surrounding that practice and began a regional and national conversation about FGM. The small team of journalists, working alongside a volunteer lawyer and psychologist, also tries to provide help to the women they are in touch with.

KRIK, Serbia

Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK) is a new independent investigative website which was founded by a team of young Serbian journalists intent on exposing organised crime and extortion in their country which is ranked as having widespread corruption by Transparency International. In their first year they have published several high-impact investigations, including forcing Serbia’s prime minister to admit that senior officials had been behind nocturnal demolitions in a Belgrade neighbourhood and revealing meetings between drug barons, the ministry of police and the minister of foreign affairs. KRIK have repeatedly come under attack online and offline for their work –threatened and allegedly under surveillance by state officials, defamed in the pages of local tabloids, and suffering abuse including numerous death threats on social media.

Maldives Independent, Maldives

Website Maldives Independent, which provides news in English, is one of the few remaining independent media outlets in a country that ranks 112 out of 180 countries on the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. In August 2016 the Maldives passed a law criminalising defamation and empowering the state to impose heavy fines and shut down media outlets for “defamatory” content. In September, Maldives Independent’s office was violently attacked and later raided by the police, after the release of an Al Jazeera documentary exposing government corruption that contained interviews with editor Zaheena Rasheed, who had to flee for her safety. Despite the pressure, the outlet continues to hold the government to account.

30 Jan 2017 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Letters, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Ilgar Mammadov

Azerbaijani opposition politician Ilgar Mammadov was jailed in 2013. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled in May 2014 that Mammadov’s arrest and continued detention was in retaliation for criticising the country’s government.

Mammadov is a leader of the Republican Alternative Movement (REAL), which he launched in 2009, and is one of Azerbaijan’s rare dissenting political voices. He was sentenced to seven years in prison after participating in an anti-government protest rally in Ismayilli, a town 200 kilometers outside Baku. Authorities arrested him on trumped-up charges of inciting the protest with the use of violence. Mammadov had previously announced his intent to run for president. Mammadov remains in jail, despite the Council of Europe repeatedly calling for his release. Azerbaijan may be expelled from the council as the country repeatedly refuses to comply with the organization’s requests. John Kirby, spokesman of the US Department of State, also called on Azerbaijan to drop all charges against Mammadov. Reports in November 2015 emerged stating that Mammadov had been tortured by prison officials, which resulted in serious injuries including broken teeth. Mammadov has remained very vocal during his time in jail, writing on his blog about political developments in Azerbaijan and refusing to write a letter asking for pardon from President Ilham Aliyev.

The following is a letter written by Ilgar Mammadov:

International investment in fossil fuel extraction is making me and other Azerbaijani political prisoners hostages to the Aliyev regime.

A thirst for freedom.

Azerbaijan has seen a crackdown on any political dissent over the past few years, with dozens of activists and critics of the regime in Baku going behind bars. So far, there’s little sign of improvement.

Though respectful of the memory of Nelson Mandela, the mass media have occasionally shed light on the late South African leader’s warm relationship with scoundrels such as Muammar Qaddafi and Fidel Castro, as well as his refusal to defend Chinese dissidents. These events have been evoked to invite critical thinking about an iconic figure and balance his place in history.

Most readers of these articles judge a figure they previously held as an idol as hypocritical or tainted. They do not ask questions about the roots of a particular contradiction. In the case of Mandela, the dictators above had supported the anti-apartheid struggle of the African National Congress, while several established democracies indulged the inhuman system of apartheid because of the diamond, oil and other industries, and particularly because of the Cold War.

After only four years in prison, even on bogus charges and a politically motivated sentence, I am nowhere near Mandela in terms of symbolising a cause of global significance. Republicanism in my country, Azerbaijan — where the internationally promoted father-to-son succession of absolute power has disillusioned millions — is hardly comparable to the fight against racial segregation. Still, I can, better than many others, explain the flawed international attitudes that help keep democrats locked in the prisons of the “clever autocrats” who are, in turn, courted by retrograde forces within today’s democracies.

I will tell the story of how plans for a giant pipeline that would suck gas from Azerbaijan to Italy, the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), impacts on Azerbaijan’s political prisoners.

In this letter I will focus only on one tension of the struggle we face here in Azerbaijan — between our democratic aspirations that enjoy only a nominal solidarity abroad, and the attempt to build a de facto monarchy which receives comprehensive support from foreign interest groups.

To be precise, I will tell the story of how plans for a giant pipeline that would suck gas from Azerbaijan to Italy, the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), impacts on Azerbaijan’s political prisoners.

I will tell the story by discussing my own case. But before I tell it, you need to know what the Southern Gas Corridor is and why my release is crucial for the morale of our democratic forces. Indeed, Council of Europe officials say my freedom is essential for the entire architecture of protection under the European Convention of Human Rights, but there is still no punishment of my jailer.

What is the Southern Gas Corridor?

The Southern Gas Corridor is a multinational piece of gas infrastructure worth $43 billion US dollars. It is designed to extract and pump 16 billion cubic metres of natural gas every year from 2018, sucking hydrocarbons from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz gas field to European and Turkish markets. The EU, Turkey, and the US are all eager to connect the pipeline to Turkmenistan so that to an extra 20-30 billion cubic metres of Turkmen gas can be added to the scheme.

Hydrocarbon extraction is the mainstay of the country’s economy. Baku signed the “contract of the century” in 1994, and has attracted western oil and gas giants ever since.

The significance of the SGC is twofold. First, the project could provide up to 8-10% of EU’s gas imports, thus reducing the union’s dependence on Russia. Secondly, it will become another platform for geopolitical access (Russians would use a slightly ominous word “penetration”) of the west to Central Asia.

How did SGC encourage more repression?

Any rational democratic government in Baku would opt for the SGC without much debate and then turn its attention to issues truly important for Azerbaijan’s sustainable economic development. The revenue generated by the project would not be viewed as vital for the country when compared to the country’s economic potential in a less monopolised and more competition-based economy.

However, since the moment when a Russian government plane took Ilham Aliyev’s barely breathing father from a Turkish military hospital to the best clinic in America, in order to smooth the transition of power, the absolute ruler of Azerbaijan has been trained to deal with great powers first and then use such deals to repress domestic political dissent second. He has kept the country’s economy almost exclusively based on selling oil and gas and importing everything else.

Recently, Aliyev has been trying to present the SGC as his generous gift to the west so that governments will not talk about human rights and democracy in Azerbaijan. At one point Aliyev was even considering unilaterally funding the entire project.

Since 2013, Aliyev has instigated an unprecedented wave of attacks on civil society, which he used to illustrate the seriousness of his ambition for energy cooperation with the west.

In the middle of this tug of war, Azerbaijan suddenly found itself short of money due to falling oil prices. It could not fund its share in the parts of SGC that ran through Turkey (TANAP) and Greece, Albania and Italy (TAP) without backing from four leading international financial institutions — the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, World Bank and Asian Development Bank.

During 2016, these institutions said their backing was subject to Azerbaijan’s compliance with the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI). In September, Riccardo Puliti, director on energy and natural resources at the EBRD, cited the resumption of the EITI membership of Azerbaijan as “the main factor” for the prospect of approval of funds for TANAP/TAP.

Together with EIB, EBRD wants to cover US $2.16 billion out of the total US $8.6 billion cost of the TANAP. TAP will cost US $6.2 billion.

What is the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative?

The EITI is a joint global initiative of governments, extractive industries, and local and international civil society organisations that aims, inter alia, to verify the amount of natural resources extracted by (mostly international) corporations and how much of the latters’ revenue is shared with host states. Its purpose, in that respect, is to safeguard transnational businesses from future claims that they have ransacked a developing nation — for instance, by sponsoring a political regime unfriendly to civil society and principle freedoms.

In April 2015, because of the unprecedented crackdown on civil society during 2013-2014, the EITI Board lowered the status of Azerbaijan in the initiative from “member” to “candidate”. This move, alongside falling oil prices, complicated funding for the Southern Gas Corridor. International backers were reluctant to be associated with the poor ethics of implementing energy projects in a country where already fragmented liberties were degenerating even further.

Hence, during 2016, several governments, especially the US, put strong political pressure on Azerbaijan. This resulted in a minor retreat by the dictatorship. Some interest groups claimed at the EITI board that this was “progress”.

The EITI board assembled on 25 October to review Azerbaijan’s situation. I appealed to the board ahead of its meeting.

Why did my appeal matter?

My appeal was heard primarily because, until I was arrested in March 2013, I was a member of the Advisory Board of what is now the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), a key international civil society segment of EITI.

In addition to my status within the EITI, the circumstances of my case — which was unusually embarrassing for the authorities — also played a role:

i) The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) had established that the true reason behind the 12 court decisions (by a total of 19 judges) for my arrest and continued detention was the wish of the authorities “to silence me” for criticising the government;

ii) The US embassy in Azerbaijan had spent an immense amount of man-hours observing all 30 sessions of my trial during five months in a remote town and concluded: “the verdict was not based on evidence, and was politically motivated”;

iii) The European Parliament’s June 2013 resolution, which carried my name in its title, had called for my immediate and unconditional release — a call reiterated in the next two EP resolutions of 2014 and 2015 on human rights situation in Azerbaijan;

iv) Since December 2014, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe had adopted eight (now nine) resolutions and decisions specifically on my case whereby it insisted on urgent release in line with the ECHR judgment.

Due to an onslaught by civil society partners during the 25 October debate, the EITI Board refused to return Azerbaijan its “member” status.

Indecision in America

I am very much obliged to the US embassy for conducting the hard labour of trial observation, but the US government representative’s stance at the EITI board meeting in October was a surprising disappointment.

Mary Warlick, the representative of the US government, insisted that Azerbaijan has made progress worth of being rewarded by EITI membership. Obviously, she was speaking for that part of the US government that wants the SGC pipeline to be built at any cost to our freedom.

A month later, in a counter-balancing act, John Kirby, spokesman of the US Department of State, called on Azerbaijan to drop all charges against me.

Samantha Power’s Facebook posting of my family photo on 10 December, the International day of Human Rights, was also touching. Power is US Permanent Representative at UN. Two years ago, she already mentioned my case in the EITI context at a conference.

Complementing her kindness, around the same time Christopher Smith, Chairman of the Helsinki Commission of the US Congress, in an interview about fresh draconian laws restricting free speech in Azerbaijan, repeated his one year old call for my release.

Yet, on 15 December, Amos Hochstein, US State Department’s Special Envoy on Energy, assured the authorities in Baku that “regardless of any political changes, the US will remain committed to its obligations under the SGC”.

Indecision in Europe

I could set out a similar pattern of European hesitation beginning with my first days in jail.

To be concise, though, let me recall only the fact that on 20 September (the same day that Rodrigo Duterte called the European Parliament “hypocritical” for its criticism of the extra-judicial executions in Philippines), a conciliatory delegation of the EP in Baku not only agreed to hear a lecture from Ilham Aliyev on “[EP] President Martin Schultz and his deputy Lubarek being enemies of the people of Azerbaijan”, but even praised the lecture as a “constructive one”, in the words of Sajjad Karim, the British MEP who had led the delegation.

Political prisoners of Azerbaijan are not worth the amount of money involved in the SGC, but European values probably are.

The aforementioned three resolutions of the European Parliament were thus crossed out as I observed from behind bars.

Two presidents of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council Of Europe (PACE) have visited me in prison, but this only highlighted the irrelevance of the body to the situation on the ground. They never stopped talking of how constructive or how ongoing their dialogue with the Azerbaijani authorities has been.

New threats

Our narrow win at the EITI Board exposes us to two new threats. (I do not discuss here the extraneous threats, which may originate from, for example, rising oil prices or collapse of the nuclear deal with Iran, i.e. anything adding confidence or bargaining power to the regime in Baku.)

One is that at the next EITI board meeting in March 2017, those driven by pressing commodity and geopolitical interests may outnumber or otherwise outpower the civil society party. If Ilham Aliyev proceeds with his cosmetic, fig leaf “reforms” or releases those political prisoners who have already pleaded for pardon or surrendered in any other way, the probability of my freedom being sacrificed will arise again.

The other threat is that instead of battling at the EITI, those interest groups may ask the international financial institutions to disconnect the SGC loans from Azerbaijan’s compliance with the EITI. These institutions are easier to convince as they are full of short-termist bank executives, rather than civil society activists concerned with the rule of law, transparency and public accountability.

The second scenario may already be in effect as rumours suggest that the World Bank has endorsed a US $800m loan to the TANAP. If so, then the postponed energy consultations between Baku and Brussels at the end of January may put the loans back on the EITI-friendly track. Political prisoners of Azerbaijan are not worth of the amount of money involved in the SGC, but European values probably are.

Deep jail horizon

Of 11 other members of the ruling body of my civic movement, REAL, three had to flee the country after my arrest, two were jailed (for 1.5 years and one month on charges not related to my case), two are not permitted to travel abroad (again on separate cases); one of them cannot even leave Baku.

From time to time, activists spend days under administrative detention designed to scare others. Nonetheless, we live in a world different from the one which tolerated and even fed apartheid.

Mandela’s fight promoted an agenda and international institutions where we can defend the values of freedom from encroachment by dictators and their business partners. This is why we should not consider the means of resisting oppression or seeking solidarity with other international arrangements any less conventional now. The problem is that when others see that our peaceful efforts are not fruitful, they turn to more radical means to end injustice.

*Mary Warlick is married to James Warlick, US co-chair of the OSCE Minsk Group mediating in the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. Therefore, initially I guessed that by being nice to the regime she might have tried to make her husband’s relations with the official Baku easier. But in mid-November, James Warlick announced his resignation from the post, apparently as he had planned, and my guess turned out to be mistaken.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1485781328870-cb0adaa0-0682-7″ taxonomies=”7145″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

Arcoiris, Honduras

Arcoiris, Honduras Jensiat, Iran

Jensiat, Iran