1 Aug 2018 | China, Magazine, News and features, Student Reading Lists

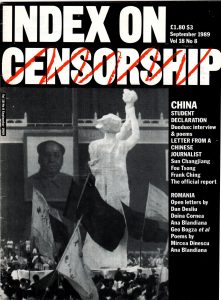

China: student declaration, the September 1989 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine here

Index has covered censorship in China since 1973. While the government’s approach has evolved in today’s digital era, in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989, key themes surrounding the suppression of political dissent and free expression remain as pressing as ever. Explore them in this reading list featuring prominent Chinese academics, activists and writers.

Tiananmen Remembered

May 2009 vol. 38 no. 2

Wang Dan, a leading figure in the 1989 protests, talks to the writer Xinran about the fallout and the legacy of Tiananmen. Wang Dan was released from prison in 1998 and exiled to the United States. He completed his PhD at Harvard University. He is chairman of the Chinese Constitutional Reform Association and on the advisory board of Wikileaks. Xinran worked as a journalist and radio presenter in China. She now lives in London. Her books include The Good Women of China (Vintage), Sky Burial (Vintage) and China Witness (Chatto & Windus).

Read the full article here.

Tiananmen Square

June 1989 vol. 18 no. 8

Student leaders Liu Xiaobo, Zhou Duo, Hou Dejian and Gao Xin declared a hunger strike in Tiananmen Square just before the massacre on the night of 3-4 June 1989. This translation of excerpts of the declaration was first published in The Independent, 10 June 1989.

Read the full article here.

From Coming back to life: written for the ‘Tiananmen mother’

December 2010 vol. 39 no. 4

This poem was written by Chinese poet Shi Tao who has faced censorship, government threats and imprisonment for his work. It was translated by English scholar Frances Wood.

Read the full article here.

A date (not) to forget: The author on why her book about Tiananmen would be well-nigh impossible to research today

April 2018 vol. 47 no. 1

China has passed a law to make telling the wrong sort of history punishable. Louisa Lim, author of a book on the Tiananmen Square massacre, says she wouldn’t be able to research her book today.

Read the full article here.

Chinese whispers

September 1999 vol. 28 no. 5

In 1999, the 10th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre passed quietly enough but as British journalist John Gittings writes, the desire for change and for democracy in China is as strong as ever.

Read the full article here.

DuoDuo’s view from death

September 1989 vol. 18 no. 8

One of China’s leading young poets Li Shizheng, known as DuoDuo, was in Tiananmen Square on the day of the massacre. He flew to Britain the day afterwards, where he was interviewed by Gregory Lee for Index.

Read the full article here.

Subscribe to the print edition Index on Censorship magazine here for £35 or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year, with a free trial).

19 Jul 2018 | News and features, Volume 46.01 Spring 2017

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1531732086773{background: #ffffff url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/FinalBullshit-withBleed.jpg?id=101381) !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Manipulating news and discrediting the media are techniques that have been used for more than a century. Originally published in the spring 2017 issue The Big Squeeze, Index’s global reporting team brief the public on how to watch out for tricks and spot inaccurate coverage. Below, Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley introduces the special feature” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left|color:%23000000″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

FICTIONAL ANGLES, SPIN, propaganda and attempts to discredit the media, there’s nothing new there. Scroll back to World War I and you’ll find propaganda cartoons satirising both sides who were facing each other in the trenches, and trying to pump up public support for the war effort. If US President Donald Trump is worried about the “unbalanced” satirical approach he is receiving from the comedy show Saturday Night Live, he should know he is following in the footsteps of Napoleon who worried about James Gillray’s caricatures of him as very short, while the vertically challenged French President Nicolas Sarkozy feared the pen of Le Monde’s cartoonist Plantu.

When Trump cries “fake news” at coverage he doesn’t like, he is adopting the tactics of Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa. Cor-rea repeatedly called the media “his greatest enemy” and attacked journalists personally, to secure the media coverage he wanted.

As Piers Robinson, professor of political journalism at Sheffield University, said: “What we have with fake news, distorted information, manipulation communication or propaganda, whatever you want to call it, is nothing new.”

Our approach to it, and the online tools we now have, are newer however, meaning we now have new ways to dig out angles that are spun, include lies or only half the story.

But sadly while the internet has brought us easy access to multitudes of sources, and the ability to watch news globally, it also appears to make us lazier as we glide past hundreds of stories on Twitter, Facebook and the digital world. We rarely stop to analyse why one might be better researched than another, whose journalism might stand up or has the whiff of reality about it.

As hungry consumers of the news we need to dial up our scepticism. Disappointingly, research from Stanford University across 12 US states found millennials were not sceptical about news, and less likely to be able to differentiate between a strong news source and a weak one. The report’s authors were shocked at how unprepared students were in questioning an article’s “facts” or the likely bias of a website.

And, according to Pew Research, 66% of US Facebook users say they use it as a news source, with only around a quarter clicking through on a link to read the whole story. Hardly a basis for making any decision.

At the same time, we are seeing the rise of techniques to target particular demographics with political advertising that looks like journalism. We need to arm ourselves with tools to unpick this new world of information.

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Credit: Ben Jennings

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Turkey

A Picture Sparks a Thousand Stories

KAYA GENÇ dissects the use of shocking images and asks why the Turkish media didn’t check them

Two days after last year’s failed coup attempt in Turkey, one of the leading newspapers in the country, Sozcu, published an article with two shocking images purportedly showing anti-coup protesters cutting the throat of a soldier involved in the coup. “In the early hours of this morning the situation at the Bosphorus Bridge, which had been at the hands of coup plotters until last night, came to an end,” the piece read. “The soldiers handed over their guns and surrendered. Meanwhile, images of one of the soldiers whose throat was cut spread over social media like an avalanche, and those who saw the image of the dead soldier suffered shock,” it said.

These powerful images of a murdered uniformed youth proved influential for both sides of the political divide in Turkey: the ultra-conservative Akit newspaper was positive in its reporting of the lynching, celebrating the killing. The secularist OdaTV, meanwhile, made it clear that it was an appalling event and it was publishing the pictures as a means of protest.

Neither publication credited the images they had published in their extremely popular articles, which is unusual for a respectable publication. A careful reader could easily spot the lack of sources in the pieces too; there was no eyewitness account of the purported killing, nor was anyone interviewed about the event. In fact, the piece was written anonymously.

These signs suggested to the sceptical reader that the news probably came from someone who did not leave their desk to write the story, choosing instead to disseminate images they came across on social media and to not do their due diligence in terms of verifying the facts.

On 17 July, Istanbul’s medical jurisprudence announced that, among the 99 dead bodies delivered to the morgue in Istanbul, there was no beheaded person. The office of Istanbul’s chief prosecutor also denied the news, and it was declared that the news was fake.

A day later, Sozcu ran a lengthy commentary about how it prepared the article. Editors accepted that their article was based on rumours and images spread on social media. Numerous other websites had run the same news, their defence ran, so the responsibility for the fake news rested with all Turkish media. This made sense. Most of the pictures purportedly showing lynched soldiers were said to come from the Syrian civil war, though this too is unverifiable. Major newspapers used them, for different political purposes, to celebrate or condemn the treatment of putschist soldiers.

More worryingly, the story showed how false images can be used by both sides of Turkey’s political divide to manipulate public opinion: sometimes lies can serve both progressives and conservatives.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

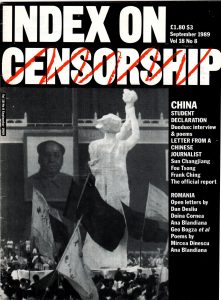

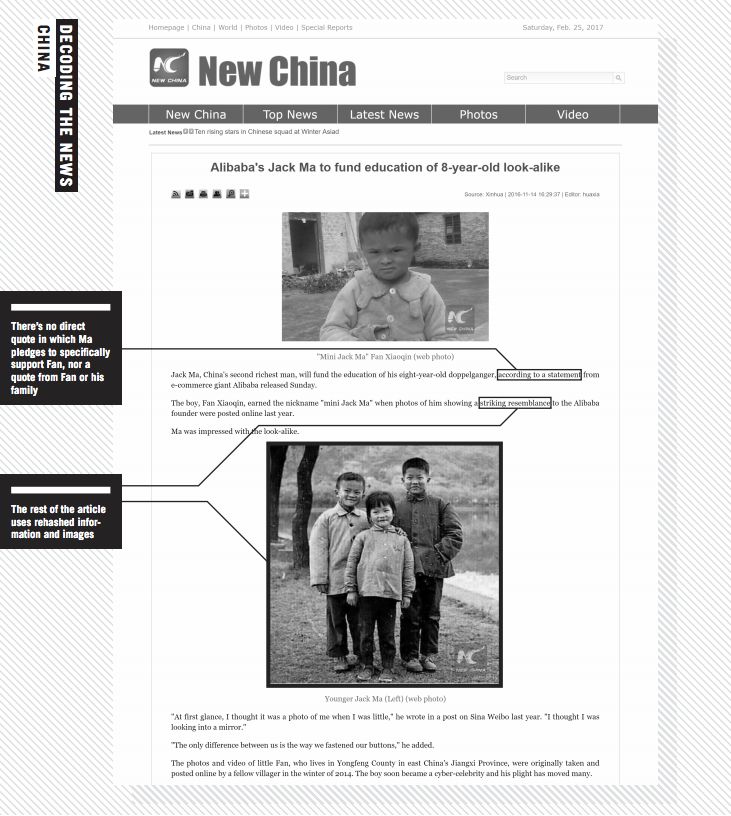

Decoding the News: China

A Case of Mistaken Philanthropy

JEMIMAH STEINFELD writes on the story of Jack Ma’s doppelganger that went too far

Jack Ma is China’s version of Mark Zuckerberg. The founder and executive chairman of successful e-commerce sites under the Alibaba Group, he’s one of the wealthiest men in China. Articles about him and Alibaba are frequent. It’s within this context that an incorrect story on Ma was taken as verbatim and spread widely.

The story, published in November 2016 across multiple sites at the same time, alleged that Ma would fund the education of eight-year-old Fan Xiaoquin, nicknamed “mini Ma” because of an uncanny resemblance to Ma when he was of a similar age. Fan gained notoriety earlier that year because of this. Then, as people remarked on the resemblance, they also remarked on the boy’s unfavourable circumstances – he was incredibly poor and had ill parents. The story took a twist in November, when media, including mainstream media, reported that Ma had pledged to fund Fan’s education.

Hints that the story was untrue were obvious from the outset. While superficially supporting his lookalike sounds like a nice gesture, it’s a small one for such a wealthy man. People asked why he wouldn’t support more children of a similar background (Fan has a brother, in fact). One person wrote on Weibo: “If the child does not look like Ma, then his tragic life will continue.”

Despite the story drawing criticism along these lines, no one actually questioned the authenticity of the story itself. It wouldn’t have taken long to realise it was baseless. The most obvious sign was the omission of any quote from Ma or from Alibaba Group. Most publications that ran the story listed no quotes at all. One of the few that did was news website New China – sponsored by state-run news agency Xinhua. Even then the quotes did not directly pertain to Ma funding Fan. New China also provided no link to where the comments came from.

Copying the comments into a search engine takes you to the source though – an article on major Chinese news site Sina, which contains a statement from Alibaba. In this statement, Alibaba remark on the poor condition of Fan and say they intend to address education amongst China’s poor. But nowhere do they pledge to directly fund Fan. In fact, the very thing Ma was criticised for – only funding one child instead of many – is what this article pledges not to do.

It was not just the absence of any comments from Ma or his team that was suspicious; it was also the absence of any comments from Fan and his family. Media that ran the story had not confirmed its veracity with Ma or with Fan. Given that few linked to the original statement, it appeared that not many had looked at that either.

In fact, once past the initial claims about Ma funding Fan, most articles on it either end there or rehash information that was published from the initial story about Ma’s doppelganger. As for the images, no new ones were used. These final points alone wouldn’t indicate that the story was fabricated, but they do further highlight the dearth of new information, before getting into the inaccuracy of the story’s lead.

Still, the story continued to spread, until someone from Ma’s press team went on the record and denied the news, or lack thereof.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

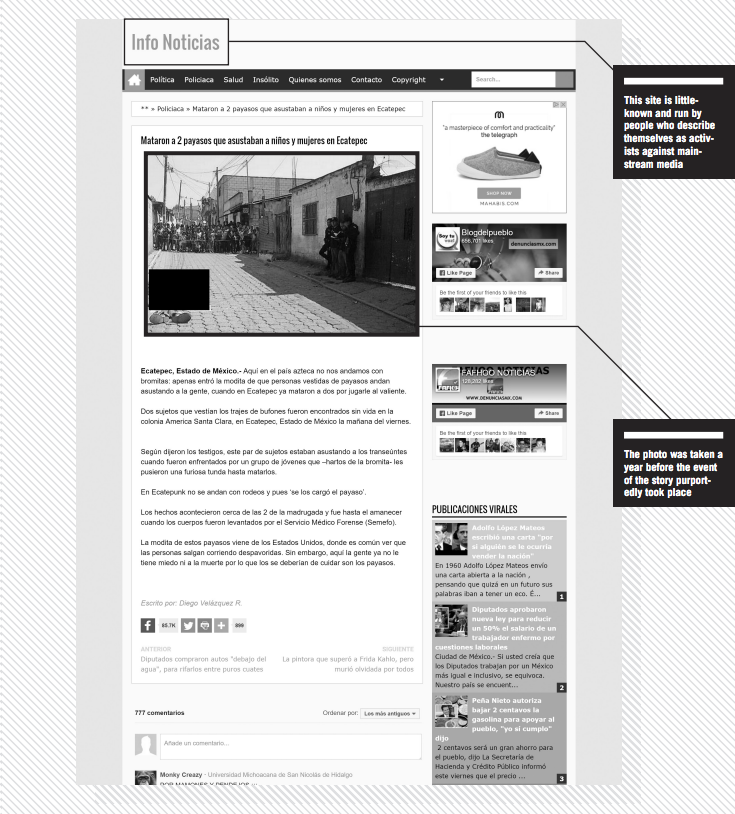

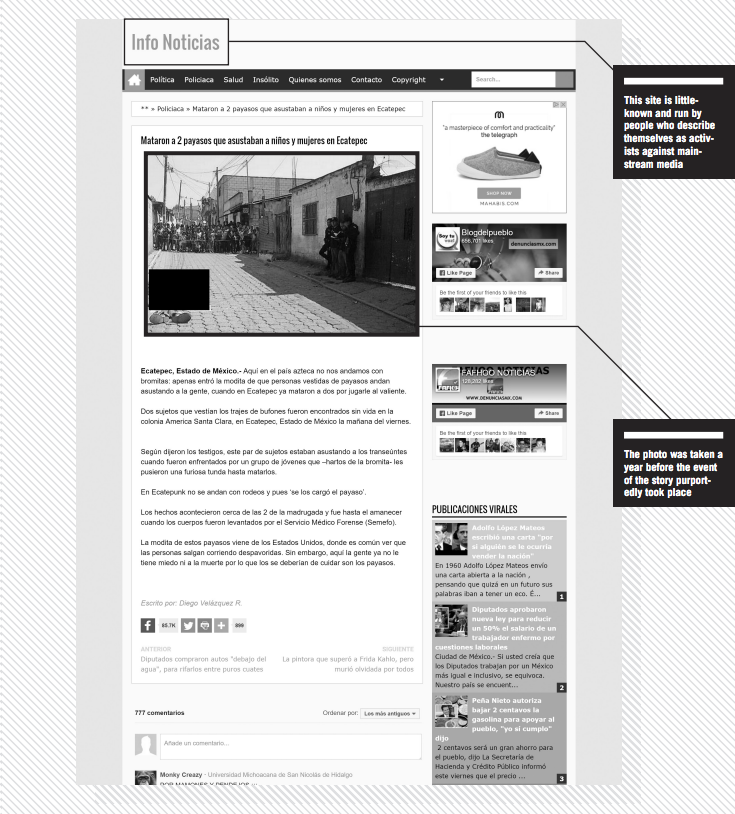

Decoding the News: Mexico

Not a Laughing Matter

DUNCAN TUCKER digs out the clues that a story about clown killings in Mexico didn’t stand up

Disinformation thrives in times of public anxiety. Soon after a series of reports on sinister clowns scaring the public in the USA in 2016, a story appeared in the Mexican press about clowns being beaten to death.

At the height of the clown hysteria, the little-known Mexican news site DenunciasMX reported that a group of youths in Ecatepec, a gritty suburb of Mexico City, had beaten two clowns to death in retaliation for intimidating passers-by. The article featured a low-resolution image of the slain clowns on a run-down street, with a crowd of onlookers gathered behind police tape.

To the trained eye, there were several telltale signs that the news was not genuine.

While many readers do not take the time to investigate the source of stories that appear on their Facebook newsfeeds, a quick glance at DenunciasMX’s “Who are we?” page reveals that the site is co-run by social activists who are tired of being “tricked by the big media mafia”. Serious news sources rarely use such language, and the admission that stories are partially authored by activists rather than by professionally-trained journalists immediately raises questions about their veracity.

The initial report was widely shared on social media and quickly reproduced by other minor news sites but, tellingly, it was not reported in any of Mexico’s major newspapers – publications that are likely to have stricter criteria with regard to fact-checking.

Another sign that something was amiss was that the reports all used the vague phrase “according to witnesses”, yet none had any direct quotes from bystanders or the authorities

Yet another red flag was the fact that every news site used the same photograph, but the initial report did not provide attribution for the image. When in doubt, Google’s reverse image search is a useful tool for checking the veracity of news stories that rely on photographic evidence. Rightclicking on the photograph and selecting “Search Google for Image” enables users to sift through every site where the picture is featured and filter the results by date to find out where and when it first appeared online.

In this case, the results showed that the image of the dead clowns first appeared online in May 2015, more than a year before the story appeared in the Mexican press. It was originally credited to José Rosales, a reporter for the Guatemalan news site Prensa Libre. The accompanying story, also written by Rosales, stated that the two clowns were shot dead in the Guatemalan town of Chimaltenango.

While most of the fake Mexican reports did not have bylines and contained very little detail, Rosales’s report was much more specific, revealing the names, ages and origins of the victims, as well as the number of shell casings found at the crime scene. Instead of rehashing rumours or speculating why the clowns were targeted, the report simply stated that police were searching for the killers and were working to determine the motive.

As this case demonstrates, with a degree of scrutiny and the use of freely available tools, it is often easy to differentiate between genuine news and irresponsible clickbait.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

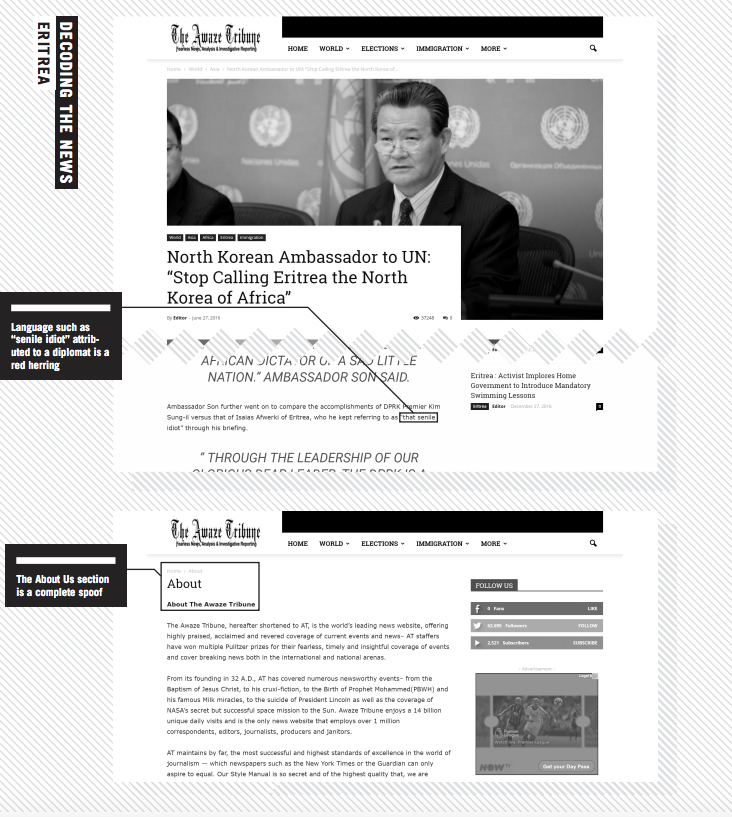

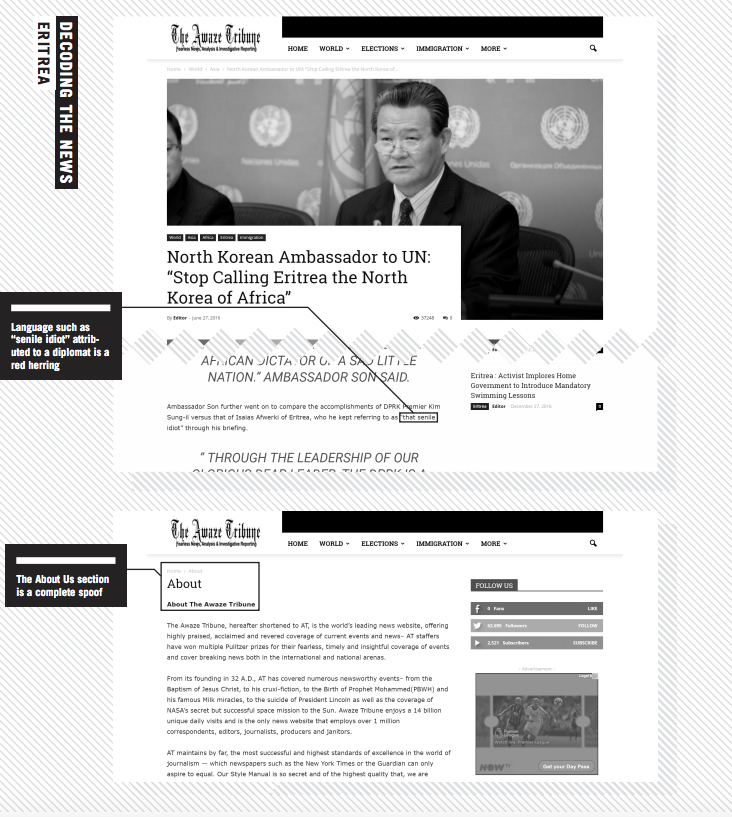

Decoding the News: Eritrea

Not North Korea

ABRAHAM T ZERE dissects the moment that Eritreans mistook saucy satire for real news

In recent years, the international media have dubbed Eritrea the “North Korea of Africa”, due to their striking similarities as closed, repressive states that are blocked to international media. But when a satirical website run by exiled Eritrean journalists cleverly manipulated the simile, the site stoked a social media buzz among the Eritrean diaspora.

Awaze Tribune launched last June with three news stories, including “North Korean ambassador to UN: ‘Stop calling Eritrea the North Korea of Africa’.”

The story reported that the North Korean ambassador, Sin Son-ho, had complained it was insulting for his advanced, prosperous, nuclear-armed nation to be compared to Eritrea, with its “senile idiot leader” who “hasn’t even been able to complete the Adi Halo dam”.

With apparent little concern over its authenticity, Eritreans in the diaspora began widely sharing the news story, sparking a flurry of discussion on social media and quickly accumulating 36,600 hits.

The opposition camp shared it widely to underline the dismal incompetence of the Eritrean government. The pro-government camp countered by alleging that Ethiopia must have been involved behind the scenes.

The satirical nature of the website should have seemed obvious. The name of the site begins with “Awaze”, a hot sauce common in Eritrean and Ethiopian cuisines. If readers were not alerted by the name, there were plenty of other pointers. For example, on the same day, two other “news” articles were posted: “Eritrea and South Sudan sign agreement to set an imaginary airline” and “Brexit vote signals Eritrea to go ahead with its long-planned referendum”.

Although the website used the correct name and picture of the North Korean ambassador to the UN, his use of “senile idiot” and other equally inappropriate phrases should have betrayed the gag.

Recently, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki has been spending time at Adi Halo, a dam construction site about an hour’s drive from the capital, and he has opened a temporary office there. While this is widely known among Eritreans, it has not been covered internationally, so the fact that the story mentioned Adi Halo should also have raised questions of its authenticity with Eritreans. Instead, some readers were impressed by how closely the North Korean ambassador appeared to be following the development.

The website launched with no news items attributed to anyone other than “Editor”, and even a cursory inspection should have revealed it was bogus. The About Us section is a clear joke, saying lines such as the site being founded in 32AD.

Satire is uncommon in Eritrea and most reports are taken seriously. So when a satirical story from Kenya claimed that Eritrea had declared polygamy mandatory, demanding that men have two wives, Eritrea’s minister of information felt compelled to reply.

In recent years, Eritrea’s tightly closed system has, not surprisingly, led people to be far less critical of news than they should be. This and the widely felt abhorrence of the regime makes Eritrean online platforms ready consumers of such satirical news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

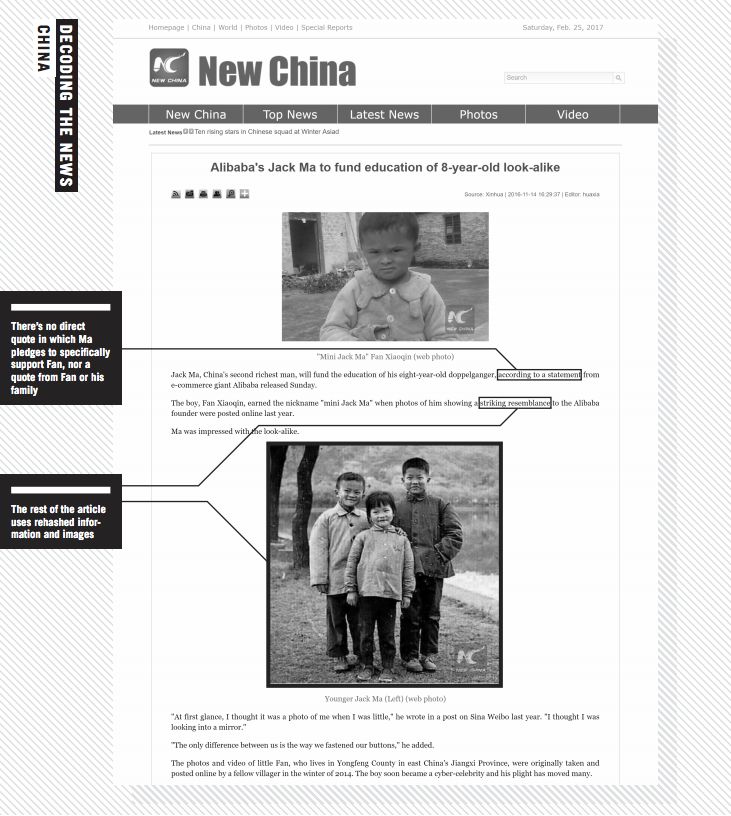

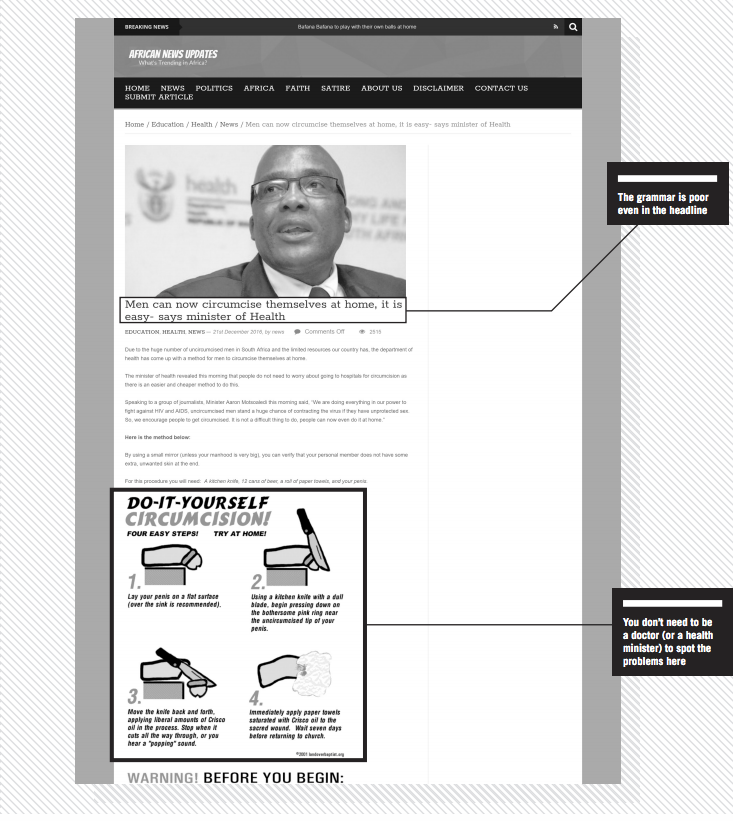

Decoding the News: South Africa

And That’s a Cut

Journalist NATASHA JOSEPH spots the signs of fiction in a story about circumcision

The smartest tall tales contain at least a grain of truth. If they’re too outlandish, all but the most gullible reader will see through the deceit. Celebrity death stories are a good example. In South Africa, dodgy “news” sites routinely kill off local luminaries like Desmond Tutu. The cleric is 85 years old and has battled ill health for years, so fake reports about his death are widely circulated.

This “grain of truth” rule lies at the heart of why the following headline was perhaps believed. The headline was “Men can now circumcise themselves at home, it is easy – says minister of health”. Circumcision is a common practice among a number of African cultural groups. Medical circumcision is also on the rise. So it makes sense that South Africa’s minister of health would be publicly discussing the issue of circumcision.

The country has also recently unveiled “DIY HIV testing kits” that allow people to check for HIV in their own homes. This is common knowledge, so casual or less canny readers might conflate the two procedures.

The reality is that most of us are casual readers, snacking quickly on short pieces and not having the time to engage fully with stories. New levels of engagement are required in a world heaving with information.

The most important step you can take in navigating this terrible new world is to adopt a healthy scepticism towards everything. Yes, it sounds exhausting, but the best journalists will tell you that it saves a lot of time to approach information with caution. My scepticism manifests as what I call my “bullshit detector”. So how did my detector react to the “DIY circumcision” story?

It started ringing instantly thanks to the poor grammar evident in the headline and the body of the text. Most proper news websites still employ sub editors, so lousy spelling and grammar are early warning signals that you’re dealing with a suspicious site.

The next thing to check is the sourcing: where did the minister make these comments? To whom? All this article tells us is that he was speaking “in Johannesburg”. The dearth of detail should signal to tread with caution. If you’ve got the time, you might also Google some key search terms and see if anyone else reported on these alleged statements. Also, is there a journalist’s name on the article? This one was credited to “author”, which suggests that no real journalist was involved in production.

The article is accompanied by some graphic illustrations of a “DIY circumcision”. If you can stomach it, study the pictures. They’ll confirm what I immediately suspected upon reading the headline: this is a rather grisly example of false “news”.

Finally, make sure you take a good look at the website that runs such an article. This one appeared on African News Updates.

That’s a solid name for a news website, but two warning bells rang for me: the first bell was clanged by other articles, which ranged from the truth (with a sensational bent) to the utterly ridiculous. The second bell rang out of control when I spotted a tab marked “satire” along the top. Click on it and there’s a rant ridiculing anyone who takes the site seriously. Like I needed any excuse to exit the site and go in search of real news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: How To

Get the Tricks of the Trade

Veteran journalist RAYMOND JOSEPH explains how a handy new tool from South Africa can teach you core journalism skills to help you get to the truth

It’s been more than 20 years since leading US journalist and journalism school teacher Melvin Mencher released his Reporter’s Checklist and Notebook, a brilliant and simple tool that for years helped journalists in training.

Taking cues from Mencher’s, there’s now a new kid on the block designed for the digital age. Pocket Reporter is a free app that leads people through the newsgathering process – and it’s making waves in South Africa, where it was launched in late 2016.

Mencher’s consisted of a standard spiral-bound reporter’s notebook, but also included tips and hints for young reporters and templates for a variety of stories, including a crime, a fire and a car crash. These listed the questions a journalist needed to ask.

Cape Town journalist Kanthan Pillay was introduced to Mencher’s notebook when he spent a few months at the Harvard Business School and the Nieman Foundation in the USA. Pillay, who was involved in training young reporters at his newspaper, was inspired by it. Back in South Africa, he developed a website called Virtual Reporter.

“Mencher’s notebook got me thinking about what we could do with it in South Africa,” said Pillay. “I believed then that the next generation of reporters would not carry notebooks but would work online.”

Picking up where Pillay left off, Pocket Reporter places the tips of Virtual Reporter into your mobile phone to help you uncover the information that the best journalists would dig out. Cape Town-based Code for South Africa re-engineered it in partnership with the Association of Independent Publishers, which represents independent community media.

It quickly gained traction among AIP’s members. Their editors don’t always have the time to brief reporters – who might be inexperienced journalists or untrained volunteers – before they go out on stories.

This latest iteration of the tool, in an age when any smartphone user can be a reporter, is aimed at more than just journalists. Ordinary people without journalism training often find themselves on the frontline of breaking news, not knowing what questions to ask or what to look out for.

Code4SA recently wrote code that makes it possible to translate the content into other languages besides English. Versions in Xhosa, one of South Africa’s 11 national languages, and Portuguese are about to go live. They are also currently working on Afrikaans and Zulu translations, while people elsewhere are working on French and Spanish translations.

“We made the initial investment in developing Pocket Reporter and it has shown real world value. It is really gratifying to see how the project is now becoming community-driven,” said Code4SA head Adi Eyal.

Editor Wara Fana, who publishes his Xhosa community paper Skawara News in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, said: “I am helping a collective in a remote area to launch their own publication, and Pocket Reporter has been invaluable in training them to report news accurately.” His own journalists were using the tool and he said it had helped improve the quality of their reporting.

Cape Peninsula University of Technology journalism department lecturer Charles King is planning to incorporate Pocket Reporter into his curriculum for the news writing and online-media courses he teaches.

“What’s also of interest to me is that there will soon be Afrikaans and Xhosa versions of the app, the first languages of many of our students,” he said.

Once it has been downloaded from the Google Play store, the app offers a variety of story templates, covering accidents, fires, crimes, disasters, obituaries and protests.

The tool takes you through a series of questions to ensure you gather the correct information you need in an interview.

The information is typed into a box below each question. Once you have everything you need, you have the option of emailing the information to yourself or sending it directly to your editor or anyone else who might want it.

Your stories remain private, unless you choose to share them. Once you have emailed the story, you can delete it from your phone, leaving no trace of it.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

This article originally appeared in the spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Kaya Genç is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine based in Istanbul, Turkey

Jemimah Steinfeld is deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Duncan Tucker is a regular correspondent for Index on Censorship magazine from Mexico

Journalist Abraham T Zere is originally from Eritrea and now lives in the USA. He is executive director of PEN Eritrea

Natasha Joseph is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine and is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is also Africa education, science and technology editor at The Conversation

Raymond Joseph is former editor of Big Issue South Africa and regional editor of South Africa’s Sunday Times. He is based in Cape Town and tweets @rayjoe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533808″][vc_custom_heading text=”There’s nothing new about fake news” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533808|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Andrei Aliaksandrau takes a look at fake news in Belarus[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532452″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fake news: The global silencer” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532452|||”][vc_column_text]April 2018

Caroline Lees examines fake news being used to imprison journalists [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88803″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229808536482″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taking the bait” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229808536482|||”][vc_column_text]April 2017

Richard Sambrook discusses the pressures click-bait is putting on journalism[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Big Squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88802″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Apr 2018 | Volume 47.01 Spring 2018, Volume 47.01 Spring 2018 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at the abuse of history and how governments and powers alike are manipulating the past across the globe.

In this podcast, we speak with historian Rana Mitter about China’s current historical narrative, broadcaster and historian Bettany Hughes about how memory affects history and giving Cleopatra her dues, as well Omar Mohammed, the man behind Mosul Eye, about the dangers of recording history under Isis.

Print copies of the magazine are available on Amazon, or you can take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Abuse of History”][vc_column_text]The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how governments and other powers across the globe are manipulating history for their own ends

With: Simon Callow, David Anderson, Omar Mohammed [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99222″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]