18 Sep 2015 | mobile, Volume 42.03 Autumn 2013

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Jemimah Steinfeld and Hannah Leung on the social benefits system in China, taken from the autumn 2013 issue. This article is a great starting point for those planning to attend the Hidden Voices; Censorship Through Omission session at the festival.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

When Liang Hong returned to her hometown of Liangzhuang, Henan province, in 2011, she was instantly struck by how many of the villagers had left, finding work in cities all across China. It was then that she decided to chronicle the story of rural migrants. During the next two years she visited over 10 cities, including Beijing, and interviewed around 340 people. Her resultant book, Going Out of Liangzhuang, which was published in early 2013, became an overnight success. In March it topped the Most Quality Book List compiled by the book channel of leading web portal Sina.

Liang’s book is unique, providing a rare opportunity for migrants to narrate their stories. They have been described as san sha (scattered sand) because they lack collective strength and power to change their circumstance. “They are invisible members of society,” Liang told Index. “They have no agency. There is a paradox here. On one hand, villagers are driven away from their homes to find jobs and earn money. But on the other hand, the cities they go to do not have a place for them.”

The central reason? China’s hukou, or household registration system. The hukou, which records a person’s family history, has existed for around 2,000 years, originally to keep track of who belonged to which family. Then, in 1958 under Mao Zedong, the hukoustarted to be used to order and control society. China’s population was divided into rural and urban communities. The idea was that farmers could generate produce and live off it, while excess would feed urban factory workers, who in turn would receive significantly better benefits of education, health care and pensions. But the economic reforms starting in the late 1970s created pressure to encourage migration from rural to urban areas. Today 52 per cent of the population live in a metropolis, with a predicted rise to 66 per cent by 2020.

In this context authorities have debated making changes to the system, or eradicating it altogether. In the 1990s some cities, including Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, started to allow people to acquire a local hukou if they bought property in the city or invested large quantities of money. In Beijing specifically, a local hukou can be acquired by joining the civil service, working for a state-owned company or ascending to the top ranks of the military.

The scope of these exceptions remains small, though, and an improvement is more a rhetorical statement than a reality. “China has been talking about reforming the hukousystem for the last 20 years. Most hukou reform measures so far are quite limited and tend to favour the rich and the highly educated. They have not changed much of the substance,” University of Washington professor Kam Wing Chan, a specialist in Chinese urbanisation and the hukou, told Index.

Thus some 260 million Chinese migrants live as second-class citizens. Shanghai, for example, has around 10 million migrant workers who cannot access the same social services as official citizens.

Of the social services, education is where the hukou system particularly stings. Fully-funded schooling and entrance exams are only offered in the parents’ hometown, where standards are lower and competition for university places higher. Charitable schools have sprung up, but they are often subject to government crackdown. Earlier this year one district in Beijing alone pledged to close all its migrant schools.

It’s not just in terms of social services that migrants suffer. Many bosses demand a local hukou and exploit those without. A labour contract law passed in 2008 remains largely ineffective and the majority of migrants work without contracts. Indeed, it was only in 2003 that migrants could join the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), and to this day the ACFTU does little to recruit them.

The main official channel to voice discontent is to petition local government. Failing that, these ex-rural residents could organise protests or strikes. Given that neither free speech nor the right to assembly is protected in China, all of these options remain largely ineffective, and relatively unlikely. In a rare case in Yunnan province, southwest China, tourism company Xinhua Shihaizi owed RMB8 million (US$1.3 million) to 500 migrant workers for a construction project. With no one fighting their battle, children joined parents and held up signs in public. In this case the company was fined. Other instances are less successful, with reports of violence either at the hands of police or thugs hired by employers being rife.

“Many of them fight or rebel in small ways to get limited justice, because they cannot fight the system on a larger scale,” noted Liang. “For example, my uncle told me that he would steal things from the factory he worked at to sell later. This was a way of getting back at his boss, who was a cruel man.” In lieu of institutional support, NGOs step in. Civil society groups have been legalised since 1994, providing they register with a government sponsor. This is not always easy and migrant workers’ organisations in particular are subject to close monitoring and control. Subsequently only around 450,000 non-profits are legally registered in China, with an estimated one million more unregistered.

But since Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Communist Party of China in March, civil society groups have grown in number. Index spoke to Geoff Crothall from China Labour Bulletin, a research and rights project based in Hong Kong. They work with several official migrant NGOs in mainland China. Crothall said that while these groups have experienced harassment in the past, there has been nothing serious of late.

Migrants themselves are also changing their approach. “Young migrant workers all have cell phones and are interested in technology and know how to use social media. So certainly things such as social media feed Weibo could be a way for them to express themselves,” Liang explained.

It’s not just in terms of new technology that action is being taken. In Pi village, just outside of Beijing, former migrant Sun Heng has established a museum on migrant culture and art. Despite being closely monitored, with employees cautioned by officials against talking to foreigners, it remains open and offers aid to migrants on the side.

There are other indications that times are changing. China’s new leaders have signalled plans to amend the hukou system later this year. Whether this is once again hot air is hard to say. But they are certainly allowing more open conversation about hukou policy reform. Just prior to the release of Liang’s book, in December 2012 the story of 15-year-old Zhan Haite became headline news when Zhan, her father and other migrants took to Shanghai’s People’s Square with a banner reading: “Love the motherland, love children”, in response to not being allowed to continue her education in the city.

Initially there was a backlash. The family were evicted from their house and her father was imprisoned for several weeks. Hostility also came from Shanghai’s hukou holders, who are anxious to keep privileges to themselves. Then something remarkable happened: Haite was invited to write an op-ed for national newspaper China Daily, signalling a potential change in tack.

It’s about time. The hukou system, which has been labelled by some as a form of apartheid, is indefensible on both a moral and economic level in today’s China. Its continuation stands to threaten the stability of the nation, as it aggravates the gulf between haves and have-nots. Reform in smaller cities is a step in the right direction, but it’s in the biggest cities where these gaps are most pronounced. And as the migration of thousands of former agricultural workers to the cities continues, that division is set to deepen if nothing else is done.

Portrait of a paperless and powerless worker

Deng Qing Ning, 37, has worked as an ayi in Beijing for the last seven years. At the moment she charges RMB15 (US$2.40) per hour for her routine cleaning services, though she is thinking of increasing her rates to RMB20 to match the market. She hasn’t yet, for fear that current clients will resist.

The word ayi in Mandarin can be used as a generic term for auntie, but it also refers to a cleaner or maid. Most ayi perform a gamut of chores, from taking care of children to cleaning, shopping and cooking.

While ayi in cities like Hong Kong are foreign live-in workers with a stipulated monthly minimum wage (currently HK$3920, US$505), domestic help in China hails from provinces outside of the cities they work. In places like Beijing and Shanghai, the hourly services of non-contractual ayi cost the price of a cheap coffee.

Deng’s story is typical of many ayi who service the homes of Beijingers. She was born in 1976 in a village outside Chongqing, in China’s southwestern Sichuan province, where her parents remain. She came to Beijing in 2006 to join her husband. He had moved up north to find work in construction after the two wed in 2004.

“In Beijing, there are more regulations and more opportunities”, she said, explaining why they migrated to China’s capital. “Everyone leaves my hometown. Only kids and elders remain.”

When she arrived in Beijing, she immediately found work as an ayi through an agency. The agency charged customers RMB25 (US$4) per hour for cleaning services and would pocket RMB10, alongside a deposit. One day, at one of the houses Deng was assigned, her client offered to pay her directly, instead of going through a middleman. The set-up was mutually beneficial.

“When I discovered there was the opportunity to break free, I took it”, she said, adding that many of the cleaning companies rip off their workers.

One perk of being an ayi is Deng’s ability to take care of her daughter. When her daughter was younger and needed supervision, she joined her mother on the job. Now that her daughter is older, Deng is able to pick her up from school.

But this is where the benefits end. Her family does not receive any social welfare. Not having a Beijing hukou means not qualifying for free local education, which makes her nine-year-old daughter a heavy financial burden. Many Beijing schools do not accept migrant children at all.

Aware of these hardships in advance, Deng and her husband were still insistent on bringing their daughter with them to the city, instead of leaving her behind to be raised by grandparents, which is a situation many children of migrant workers face.

“The education in Beijing is better than back home,” she explained. Her daughter attends a local migrant school, a spot secured after they bargained for her to take the place of their nephew. Her brother-in-law’s family had just moved back home because their children kept falling ill.

Deng has to cover some of the fees and finds the urban education system unfair, but she highlights how difficult it is to voice these frustrations.

“Many Beijing kids do not even have good academic records. Our children may be better than theirs. But they take care of Beijingers first.”

She wishes the government would establish more schools; her daughter’s class size has increased three times during the school year. Again, there is nothing they can do and few people she can talk to, she says. It’s not like they have the political or business guangxi (connections) or know a local teacher who can get their daughter admission anywhere else.

Deng’s younger brother, born in 1986, followed his sister to Beijing five years ago and found employment as a construction worker. Three years back Deng received a dreaded phone call. Her brother had been in a serious accident on a construction site, where he tripped over an electrical wire and tumbled down a flight of stairs. He was temporarily blinded due to an injury that impaired his nerves.

The construction site had violated various safety laws. To the family’s relief, the supervisor of the project footed the hospital bills in Beijing’s Jishuitan Hospital, which amounted to more than RMB20,000 (US$3,235). During this time, Deng had to curb her working hours to attend to her brother, but she felt grateful given the possibility of a worse scenario. Her brother’s vision never fully recovered and he returned to their hometown shortly after.

Deng is looking forward to the time when they can all reunite, hopefully once her daughter reaches secondary school. More opportunities are developing in her hometown, which makes a return to Sichuan and relief from her paperless status much more appealing.

Jemimah Steinfeld worked as a reporter in Beijing for CNN, Huffington Post and Time Out Beijing. At present she is writing a book on Chinese youth culture.

Hannah Leung is an American-born Chinese freelance journalist who has spent the past four years in China. She is currently living in Beijing.

© Jemimah Steinfeld and Hannah Leung and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the autumn 2013 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

16 Sep 2015 | Magazine

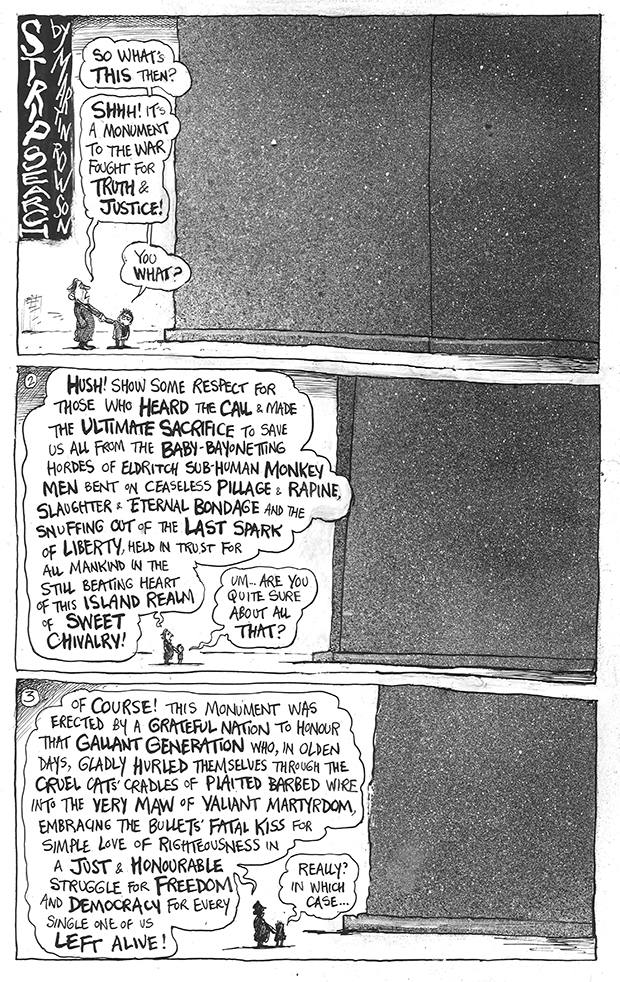

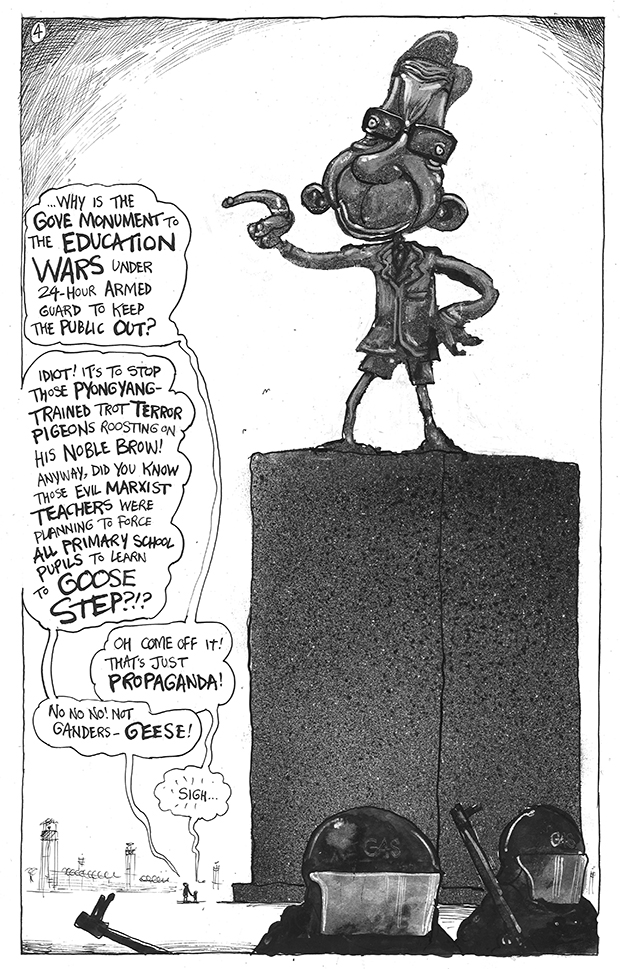

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by cartoonist and author Martin Rowson, who regularly draws for the magazine, on the power of propaganda in wartime, taken from the spring 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the War, Censorship and Propaganda: Does It Work session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

As a political cartoonist, whenever I’m criticised for my work being unrelentingly negative, I usually point my accusers towards several eternal truths.

One is that cartoons, along with all other jokes, are by their nature knocking copy. It’s the negativity that makes them funny, because, at the heart of things, funny is how we cope with the bad – or negative – stuff.

Whether it’s laughing at shit, death or the misfortunes of others, without this hard-wired evolutionary survival mechanism that allows us to laugh at the awfulness running in parallel with being both alive and human, apes with brains the size of ours would go insane with existential terror as soon as the full implications of existence sink in. Which, for most people, would be when you’re around three years old.

And if that doesn’t persuade them, I usually then try to describe that indescribable but palpable transubstantiation that occurs when you shift from the negative to the positive, and a cartoon sinks from being satire to becoming propaganda.

Though here, of course, I’m not being entirely honest, because in many ways cartoons are propaganda in its purest form. This is because the methodology of the political cartoon has most in common with the practices of sympathetic magic and, likewise, its purposes are invariably malevolent.

Indeed, I’ve often described caricature in particular and political cartooning more generally as a type of voodoo, doing damage at a distance with a sharp object, in this case (usually) a pen.

Certainly the business of caricature is a kind of shamanist shape-shifting, distorting the appearance of the victim in order to bring them under the control of the cartoonist and subjecting them thereafter to ridicule or opprobrium. In short, political cartoons should truly be classified not as comedy but as visual taunts. And taunts, of course, have been an integral ingredient of warfare for millennia.

Within the twisted plaiting of taunts, posturing and brinkmanship that ultimately ended in the hecatombs of the Western Front in World War I you can just about tease out one thread trailing back to a cartoon.

The original sketch for the allegorical 1896 cartoon Nations of Europe: Join in Defence of Your Faith! was by Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, though he left the job of the finished artwork to professionals. Its purpose was to stiffen the resolve of European leaders against the “yellow peril” coming from east Asia, and to this end the Kaiser presented a copy of the cartoon to his cousin Tsar Nicholas II of Russia.

It’s generally agreed that the cartoon played a small but significant part in influencing the Tsar’s confrontational policy towards Japan, which ended in Russia’s humiliating defeat in the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese war.

The subsequent revolutions, regional wars and growing European instability erupted nine years later with the general mobilisation of the Great Powers, and the cartoonists were mobilised along with everyone else.

Although a perennial taunt against the Germans is that they have no sense of humour, they had as rich a tradition of visual satire as anyone else. In the pages of both Punch and the German satirical paper Simplicissimus, the enemy was caricatured identically as alternatively preposterous and terrifying. Both sides showed the other in league with skeletal personifications of Death, or transformed into fat clowns, foul or dangerous animals or, in British cartoons about Germans, as sausages.

There were also scores of cartoons showing German soldiers bayoneting Belgian babies in portrayals of “The Beastly Hun” and, later, cartoons showing the Germans harvesting the corpses of slain soldiers for fats to advance their war effort.

All sides taunted each other by attacking their nations’ supposed leaders, using the caricaturist’s typical tools. Thus the Kaiser, mostly thanks to his waxed moustache, acted as a synecdoche for Germany’s defining perfidy. In one cartoon from 1915, when Britain’s George V stripped his cousin, the Kaiser, of his Order of the Garter, his garterless stocking slips down, revealing a black and hairy simian leg. In 1914, meanwhile, the German cartoonist Arthur Johnson (his father was an American) showed the British Royal Family, German by descent, in a camp for enemy aliens.

These taunting cartoons bore little relation to the realities of modern warfare, and most of them would now be dismissed purely as rather ham-fisted propaganda. This shouldn’t downplay their effectiveness, however.

A century earlier Napoleon Bonaparte admitted he feared the damage done by James Gillray’s caricatures of him more than he feared any general, because Gillray always drew him as very short. (To bring this up to date, Le Monde’s cartoonist Plantu told me that every time he drew Nicolas Sarkozy as short, Sarkozy complained personally to his editor; the next cartoon would make him even shorter, and Sarkozy would complain again, until in the end Plantu drew the French president as just a head and feet.)

Nonetheless, an unforeseen consequence of this barrage of caricature was that in the end people stopped believing it to be anything more than merely caricature: the truth that should be exposed by the exaggeration got lost. In the 1930s, many people assumed reports of the genuine atrocities of the Nazis were, like the bayoneted babies or harvested corpses blamed on the Kaiser, just propaganda.

Posterity shouldn’t concern cartoonists. We’re just journalists responding to events with a raw immediacy. This is what gives the medium a great deal of its heft.

Some cartoons, however, encapsulate a time or an event and so become part of the more general visual language. Gillray’s The Plum Pudding in Danger is a perfect example, depicting the specific geopolitical struggle between William Pitt and Napoleon in 1805, while also capturing eternal truths about geopolitics itself. But I’m not aware of any political cartoons from World War I that do the same thing.

And yet the medium operates in many ways, and the most effective and popular cartoonist of World War I was undoubtedly Bruce Bainsfather, a serving artillery officer who drew gag cartoons about the slapstick of everyday life in the trenches in his series featuring “Old Bill”. The serving soldiers loved these cartoons, and they are another instance of humour being used to make the harshest imaginable reality simply bearable.

The other truly great cartoon to emerge from the World War I was published after it was all over. In his extraordinarily prophetic drawing Peace and Future Cannon Fodder for the Daily Herald, Will Dyson showed the Allied victors of the war exiting the Versailles peace conference and the French prime minister Georges Clemenceau saying: “Curious! I seem to hear a child weeping.” Behind a pillar a naked infant labelled “1940 class” is crying into its folded arms.

None of the protagonists in the next war doubted the power or importance of cartoons. Again, they were used by all sides to taunt and vilify their foes, perhaps most notoriously in Der Sturmer, the notorious anti-semitic paper edited by Julius Streicher, later hanged at Nuremburg.

Simplicissimus was, once more, taunting the British, this time drawing wartime prime minister, Winston Churchill, as a fat and murderous drunk; in the Soviet Union Stalin’s favourite cartoonist, Boris Yefimov, returned the compliment to the Nazi leadership (Yefimov’s older brother Mikhail first employed him on Pravda before being purged and executed in 1940; Boris survived him by 68 years, dying aged 108 in 2008). No cartoonist in either country would have dared caricature their own totalitarian politicians, but they were given full rein to exercise their skills on their nation’s enemies. In Britain, with its largely legally tolerated history of visual satire going back to 1695, things were slightly different, though also sometimes the same.

The New Zealand-born cartoonist David Low discovered in 1930 from a friend that Hitler, three years away from taking power in Germany, was an admirer of his work. Low did what any other cartoonist would do in similar circumstances and acknowledged his famous fan by sending him a signed piece of original artwork, inscribed “From one artist to another”.

It’s unknown what happened to the cartoon – maybe it was with him right to the end, in the bunker – but it soon became apparent that Hitler had mistaken Low’s attacks on democratic politicians for attacks on democracy itself. He was soon disabused. Low harried the Nazis all the way from the simple slapstick of The Difficulty of Shaking Hands with Gods of November 1933 to the bitterness of his iconic cartoon Rendezvous in September 1939, so much so that in 1936 British Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, after a weekend’s shooting at Hermann Goering’s Bavarian hunting lodge, told Low’s proprietor at the Evening Standard, Lord Beaverbrook, to get the cartoonist to ease up as his work was seriously damaging good Anglo-German relations. Low responded by producing a composite cartoon dictator called “Muzzler”.

The Nazis had a point that Low entirely understood, and it was why he, along with many other cartoonists – Victor “Vicky” Weisz, Leslie Illingworth and even William Heath Robinson – were all on the Gestapo’s death list. In a debate on British government propaganda in 1943, a Tory MP said Low’s cartoon were worth all the official propaganda put together because Low portrayed the Nazis as “bloody fools”. Low himself later expanded on the point, comparing his work, which undermined the Nazis through mockery, with the work of pre-war Danish cartoonists who unanimously drew them as terrifying monsters. Low’s point was that it’s much easier to imagine you can beat a fool than a monster, and taunting your enemies as being unvanguishably frightening is no taunt at all.

The enduring efficacy of cartoons’ dark and magical voodoo powers were acknowledged in victory, when both Low and Yefimov were official court cartoonists at the Nuremburg war crimes tribunals (Low claimed Goering tried to outstare him from the dock): now the taunting was part of the humiliation served up with the revenge. Likewise, when Mussolini was executed by Italian partisans, the editor of the Evening Standard, Michael Foot, marked the dictator’s demise by giving over all eight pages of the paper to Low’s cartoons of Mussolini’s life and career.

Of course Low, unlike Yefimov, was actively hostile on the Home Front as well, producing cartoons critical of both the military establishment and Churchill. When Low’s famous creation Colonel Blimp, the portly cartoon manifestation of boneheaded reactionary thinking, took on fresh life in the Powell and Pressburger movie The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Churchill tried to have the film banned. When the Daily Mirror’s cartoonist Philip Zec responded to stories about wartime profiteering by contrasting them with attacks on merchant shipping in his famous cartoon The Price of Petrol has Been Increased by One Penny – Official, both Churchill and Home Secretary Herbert Morrison seriously considered shutting down the newspaper. (When the Guardian cartoonist Les Gibbard pastiched Zec’s cartoon during the Falklands war 40 years later, the Sun called for him to be tried for treason.)

And yet cartoons, for all their voodoo power, can still spiral off into all sorts of different ambiguities thanks to the way they inhabit different spheres of intent. Are they there to make us laugh, or to destroy them? Or both?

Ronald Searle drew his experiences while he was a prisoner of war of the Japanese, certainly on pain of death had the drawings been discovered, but taking the risk in order to stand witness to his captors’ crimes. Just a few years later, many of his famous St Trinian’s cartoons don’t just deal with the same topics – cruelty and beheadings – but share identical composition with his prisoner of war drawings.

And when Carl Giles, creator of the famous cartoon family that mapped and reflected post-war British suburban life weekly in the Sunday Express, was present as an official war correspondent at the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, the camp’s commandant, Josef Kramer, revealed he was a huge fan of Giles’ work and gave him his pistol, a ceremonial dagger and his Nazi armband in exchange for the promise that Giles would send him a signed original. As Giles explained later, he failed to keep his part of the bargain because by the time he got demobbed Kramer had been hanged for crimes against humanity.

Those twinned qualities of taunting and laughter go some way to explaining the experience of cartoonists in the so-called war on terror, if not the power of their work. In the aftermath of 9/11, in the Babel of journalistic responses to what was without question the most visual event in human history, then visually re-repeated by the media that had initially reported it, the cartoonists were the ones who got it in the neck. While columnists wrote millions of words of comment and speculation, and images captured by machines were broadcast and published almost ceaselessly, the images produced via a human consciousness were, it seems, too much to stomach for many. Cartoonists had their work spiked, or were told to cover another story (there were no other stories). In the US some cartoonists had their copy moved to other parts of the paper, or were laid off. One or two even got a knock on the door in the middle of the night from the Feds under the provisions of the Patriot Act.

Despite a concerted effort by some American strip cartoonists to close ranks on Thanksgiving Day 2001 and show some patriotic backbone, the example of Beetle Bailey flying on the back of an American Eagle didn’t really act as a general unifier. Unlike in previous wars, there was no unanimity of purpose among cartoonists. An editorial in The Daily Telegraph accused me, along with Dave Brown of The Independent and The Guardian’s Steve Bell, of being “useful idiots” aiding the terrorist cause due to our failure to fall in line.

The war on terror and its Iraqi sideshow were anything but consensus wars, and many cartoonists articulated very loudly their misgivings. These included Peter Brookes of the Murdoch-owned Times drawing cartoons in direct opposition to his paper’s editorial line. This has always been one of visual satire’s greatest strengths: sometimes a cartoon can undermine itself.

Moreover, because a majority of cartoons were back in their comfort zone of oppositionism, the taunting had less of the whiff of propaganda about it. Nor was there ever any suggestion in Britain of government censorship of any of this.

That said, the volume of censuring increased exponentially, thanks entirely to the separate but simultaneous growth in digital communication and social media. Whereas, previously, cartoons might elicit an outraged letter to an editor – let alone a death threat from the Gestapo – the internet allowed a global audience to see material to which thousands of people responded, thanks to email, with concerted deluges of hate email and regular death threats. I long since learned to dismiss an email death threat as meaningless – a real one requires the commitment of finding my address, a stamp and possibly a body part of one of my loved ones – but it’s the thought that counts.

More to the point was the second front in the culture-struggle at the heart of the war on terror, in which both sides fought to take greater offence. Amid the bombs, bullets and piles of corpses across Iraq, Afghanistan, Bali, Madrid, London and all the other places, the greatest harm you could suffer, it seemed was that you might be “offended”. People sent me hate emails and threatened to kill me and my children because they were “offended” by my depiction of George Bush, or by a cartoon criticising Israel, or a stupid humourous drawing of anything that might mildly upset them or their beliefs.

It was into this atmosphere that the row over the cartoons of Mohammed published by the Danish newspaper Jyllands Posten erupted, resulting in the deaths of at least 100 people (none of them cartoonists, but most of them Muslims, and many shot dead by Muslim soldiers or policemen). But that, of course, is another story. And – who knows? – may yet prove to be another war.

Martin Rowson’s cartoons appear regularly in The Guardian and Index on Censorship. His books include The Dog Allusion, Giving Offence and Fuck: the Human Odyssey.

© Martin Rowson and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the spring 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine, with a special report on propaganda and war. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.