23 Sep 2015 | Magazine

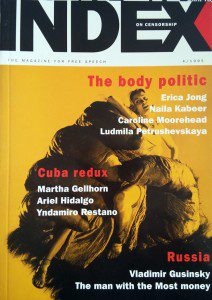

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by author Erica Jong, on pornographic material in art and literature, taken from our summer 1995 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend The body politic: censorship and the female body session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

Pornographic material has been present in the art and literature of every society in every historical period. What has changed from epoch to epoch – or even from one decade to another – is the ability of such material to flourish publicly and to be distributed legally.

After nearly 100 years of agitating for freedom to publish, we find that the enemies of freedom have multiplied, rather than diminished. They are Christians, Muslims, oppressive totalitarian regimes, even well- meaning social libertarians who happen to be feminists, teachers, school boards, librarians. This should not surprise us since, as Margaret Mead pointed out 40 years ago, the demand for state censorship is usually ‘a response to the presence within the society of heterogeneous groups of people with differing standards and aspirations.’ As our culture becomes more diverse, we can expect more calls for censorship rather than fewer.

Mark Twain’s notorious 1601 ... Conversation As It Was By The Social Fireside, In The Time of The Tudors fascinates me because it demonstrates Mark Twain’s passion for linguistic experiment and how allied it is with his compulsion toward ‘deliberate lewdness’.

The phrase ‘deliberate lewdness’ is Vladimir Nabokov’s. In a witty afterword to his ground-breaking 1955 novel Lolita, he links the urge to create pornography with ‘the verve of a fine poet in a wanton mood’ and regrets that ‘in modern times the term “pornography” connotes mediocrity, commercialism and certain strict rules of narration.’ In contemporary porn, Nabokov says, ‘action has to be limited to the copulation of cliches.’ Poetry is always out of the question . ‘Style, structure, imagery should never distract the reader from his tepid lust.’

In choosing to write from the point of view of ‘the Pepys of that day, the same being cup-bearer to Queen Elizabeth’ in 1601, Mark Twain was transporting himself to a world that existed before the invention of sexual hypocrisy. The Elizabethans were openly bawdy. They found bodily functions funny and sex arousing to the muse. Restoration wits and Augustan satirists had the same openness to bodily functions and the same respect for Eros. Only in the nineteenth century did prudery (and the threat of legal censure) begin to paralyse the author‘s hand. Shakespeare, Rochester and Pope were far more fettered politically than we are, but the fact was that they were not required to put condoms on their pens when the matter of sex arose. They were pleased to remind their readers of the essential messiness of the body. They followed a classical tradition that often expressed moral indignation through scatology, ‘Oh Celia, Celia, Celia shits,’ writes Swift, as if she were the first woman in history to do so. In his so-called ‘unprintable poems’, Swift is debunking the conventions of courtly love – as well as expressing his own deep misogyny – but he is doing so in a spirit that Catullus and juvenal would have recognised. The satirist lashes the world to bring the world to its senses. It does the dance of the satyrs around our follies.

Twain’s scatology serves this purpose as well, but it is also a warm-up for his creative process, a sort of pump-priming. Stuck in the prudish nineteenth century, Mark Twain craved the freedom of the ancients. In championing ‘deliberate lewdness’ in 1601, he bestowed the gift of freedom on himself.

Even more interesting is the fact that Mark Twain was writing 1601 during the very same summer (1876) that he was ‘tearing along on a new book’ – the first 16 chapters of a novel he then referred to as ‘Huck Finn’s autobiograph’. This conjunction is hardly coincidental. 1601 and Huckleberry Finn have a great deal in common besides linguistic experimentation. According to Justin Kaplan, ‘both were implicit rejections of the taboos and codes of polite society and both were experiments in using the vernacular as a literary medium.’

In order to find the true voice of a book, the author must be free to play without fear of reprisals. All writing blocks come from excessive self-judgement, the internalised voice of the critical parent telling the author’s imagination that it is a dirty little boy or girl. ‘Hah!’ says the author, ‘I will flaun t the voice of parental propriety and break free!’ This is why pornographic spirit is always related to unhampered creativity. Artists are fascinated with filth because we know that in it everything human is born. Human beings emerge between piss and shit and so do novels and poems. Only by letting go of the inhibition that makes us bow to social propriety can we delve into the depths of the unconscious. We assert our freedom with pornographic play. If we are lucky, we keep that freedom long enough to create a masterpiece like Huckleberry Finn.

But the two compulsions are more than just related; they are causally intertwined.

When Huckleberry Finn was published in 1885, Louisa May Alcott put her finger on exactly what mattered about the novel even as she condemned it: ‘If Mr Clemens cannot think of something better to tell our pure- minded lads and lasses, he had best stop writing for them.’ What Alcott didn’t know was that ‘our pure-minded lads and lasses’ aren’t. But Mark Twain knew. It is not at all surprising that during that summer of high scatological spirits Twain should also give birth to the irreverent voice of Huck. If Little Women fails to go as deep as Twain’s masterpiece, it is precisely because of Alcott’s concern with pure mindedness. Niceness is ever the enemy of art. If you worry about what the neighbours, critics, parents and supposedly pure-minded censors think, you will never create a work that defies the restrictions of the conscious mind and delves into the world o f dreams.

The artist needs pornography as a way into the unconscious and history proves that if this licence is not granted, it will be stolen. Mark Twain had 1601 privately printed. Picasso kept pornographic notebooks that were only exhibited after his death.

1601 is deliberately lewd. It delights in stinking up the air of propriety. It delights in describing great thundergusts of farts which make great stenches and pricks which are stiff until cunts ‘take ye stiffness out of them’. In the midst of all this ribaldry, the assembled company speaks of many things – poetry, theatre, art, politics. Twain knew that the muse flies on the wings of flatus, and he was having such a good time writing this Elizabethan pastiche that the humour shines through a hundred years and twenty later. I dare you to read 1601 without giggling and guffawing.

Erica Jong became internationally famous in 1973-4 with the publication of her novel Fear of Flying, which sold over 10 million copies worldwide. She has also written several collections of poetry and six further novels, most recently Any Woman’s Blues

Excerpted from a paper delivered at a conference on Expression, Offence and Censorship, organised by the Institute for Public Policy Research in June 1995. A full report of the conference, including contributions from Bernard Williams, Michael Grade, Clare Short MP and Chris Smith MP will be published shortly. Details from IPPR, 30-32 Southampton Street, London WC2E 7RA, UK

© Erica Jong and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the summer 1995 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

18 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.01 Spring 2015

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is and article by Ismail Einashe on television journalist Temesghan Debesai’s escape from Eritrea, taken from the spring 2014 issue. This article is a great starting point for those planning to attend the A New Home: Asylum, Immigration and Exile in Today’s Britain session at the festival.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

Television journalist Temesghen Debesai had waited years for an opportunity to make his escape, so when the Eritrean ministry of information sent him on a journalism training course in Bahrain he was delighted, but fearful too. On arrival in Bahrain, he quietly evaded the state officials who were following him and got in touch with Reporters Sans Frontières. Shortly after he met officials from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees who verified his details. He then went into hiding for two months so the Eritrean officials in Bahrain could not catch up with him and eventually escaped to Britain.

Debesai told no one of his plans, not even his family. He was concerned he was being watched. He says a “state of paranoia was everywhere” and there was no freedom of expression. Life in Eritrea, he explains, had become a “psychological prison”.

After graduating top of his class from Eritrea’s Asmara University, Debesai became a well-known TV journalist for state-run news agency Erina Update. But from 2001, the real crackdown began and independent newspapers such as Setit, Tsigenai, and Keste Debena, were shut down. In raids journalists from these papers were arrested en masse. He suspects many of those arrested were tortured or killed, and many were never heard of again. No independent domestic news agency has operated in Eritrea since 2001, the same year the country’s last accredited foreign reporter was expelled.

The authorities became fearful of internal dissent. Debesai noticed this at close hand having interviewed President Afwerki on several occasions. He describes these interviews as propaganda exercises because all questions were pre-agreed with the minister of information. As the situation worsened in Eritrea, the post-liberation haze of euphoria began to fade. Eritrea went into lock-down. Its borders were closed, communication with the outside world was forbidden, travel abroad without state approval was not allowed. Men and women between the ages of 18 and 40 could be called up for indefinite national service. A shoot-to-kill policy was put in operation for anyone crossing the border into Ethiopia.

Debesai felt he had no other choice but to leave Eritrea. As a well-known TV journalist he could not risk walking across into Sudan or Ethiopia, so he waited until he got the chance to leave for Bahrain.

Eritrea was once a colony of Italy. It had come under British administrative control in 1941, before the United Nations federated Eritrea to Ethiopia in 1952. Nine years later Emperor Haile Selassie dissolved the federation and annexed Eritrea, sparking Africa’s longest war. This long bitter war glued the Eritrean people to their struggle for independence from Ethiopia. Debesai, whose family went into exile to Saudi Arabia during the 1970s, returned to Eritrea as a teenager in 1992, a year after the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front captured the capital Asmara.

For Debesai returning to Asmara had been a “personal choice”. He wanted to be a part of rebuilding his nation after a 30-year conflict, and besides, he says, life in post-war Asmara was “socially free”, a welcome antidote to conservative Saudi life. Those heady days were electric, he says. An air of “patriotic nationalism” pervaded the country. Women danced in the streets for days welcoming back EPLF fighters. Asmara had remained largely unscathed during the war thanks to its high mountain elevation. Much of its beautiful 1930s Italian modernist architecture was intact, something Debesai was delighted to see.

But those early signs of hope that greeted independence quickly soured. By 1993 Eritreans overwhelmingly voted for independence, and since then Eritrea has been run by President Isaias Afwerki, the former rebel leader of the EPLF. Not a single election has been held since the country gained independence, and today Eritrea is one of the world’s most repressive and secretive states. There are no opposition parties and no independent media. No independent public gatherings or civil society organisations are permitted. Amnesty International estimates there are 10,000 prisoners of conscience in Eritrea, who include journalists, critics, dissidents, as well as men and women who have evaded conscription. Eritrea is ranked the worst country for press freedoms in the world by Reporters Sans Frontières.

The only way for the vast majority of Eritreans to flee their isolated, closed-off country is on foot. They walk over the border to Sudan and Ethiopia. The United Nations says there are 216,000 Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia and Sudan. By the end of October 2014, Sudan alone was home to 106,859 Eritrean refugees in camps at Gaderef and Kassala in the eastern, arid region of the country.

In Ethiopia, Eritrean refugees are found mostly in four refugee camps in the Tigray region, and two in the Afar region in north-eastern Ethiopia.

During the first 10 months of 2014, 36,678 Eritreans sought refuge across Europe, compared to 12,960 during the same period in 2013. Most asylum requests were to Sweden (9,531), Germany (9,362) and Switzerland (5,652). The UN says the majority of these Eritrean refugees have arrived by boat across the Mediterranean. The majority of them are young men, who have been forced into military conscription. All conscripts are forced to go to Sawa, a desert town and home to a military camp, or what Human Rights Watch has called an open-air prison. Many young men see no way out but to leave Eritrea. For them, leaving on a perilous journey for a life outside their home country is better than staying put. The Eritrean refugee crisis in Europe took a sharp upward turn in 2014, as the UNHCR numbers show. And tragedies, like the drowning of hundreds of Eritrean refugees off the Italian island of Lampedusa in October 2013, demonstrate the perils of the journey west and how desperate these people are.

Even when Eritrean refugees go no further than Sudan and Ethiopia, they face a grim situation. According to Lul Seyoum, director of International Centre for Eritrean Refugees and Asylum Seekers (ICERAS), Eritrean refugees in a number of camps inside Sudan and Ethiopia face trafficking, and other gross human rights violations. They are afraid to speak and meet with each other. She said, that though information is hard to get out, many Eritreans find themselves in tough situations in these isolated camps, and the situation has worsened since Sudan and Eritrea became closer politically.

Eritrea had a hostile relationship with Sudan during the 1990s. It supported the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, much to the anger of President Al Bashir who was locked in a bitter war with the people of now-independent South Sudan. Today tensions have eased considerably, and President Afwerki has much friendly relations with Sudan to the detriment of then tens of thousands of Eritrean refugees in Sudan.

A former Eritrean ministry of education official, who is a refugee now based in the UK and who does not want to be named because of safety fears, believes there’s no freedom of expression for Eritreans in Ethopian camps, such as Shimelba.

The official says in 2013 a group of Eritrean refugees came together at a camp to express their views on the boat sinking near Lampedusa and they were abused by the Ethiopian authorities who then fired at them with live bullets.

Seyoum believes that the movement of Eritreans in camps in Ethiopia is restricted. “The Ethiopian government does not allow them to leave the camps without permission,” she says. Even for those who get permission to leave very few end up in Ethiopia, instead through corrupt mechanisms are trafficked to Sudan. According to Human Rights Watch, hundreds of Eritreans have been enslaved in torture camps in Sudan and Egypt over the past 10 years, many enduring violence and rape at their hands of their traffickers in collusion with state authorities.

Even when Eritreans make it to the West, they are still afraid to speak publicly and many are fearful for their families back home. Now based in London, Debesai is a TV presenter at Sports News Africa. As an exile who has taken a stance against the regime of President Afewerki, he has faced harassment and threats. He is harassed over social media, on Twitter and Facebook. Over coffee, he shows me a tweet he’s just received from Tesfa News, a so-called “independent online magazine”, in which they accuse him of being a “backstabber” against the government and people of Eritrea. Others face similar threats, including the former education ministry official.

For this piece, a number of Eritreans said they did not want to be interviewed because they were afraid of the consequences. But Debesai said: “It takes time to overcome the past, so that even for those in exile in the West the imprisonment continues.” He adds: “These refugees come out of a physical prison and go into psychological imprisonment.”

© Ismail Einashe and Index on Censorship