7 Jun 2017 | Artistic Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RyaGg3Me38k&feature=youtu.be”][vc_column_text]Additional reporting by Mary Meisenzahl

Following similar events in the USA and Australia, the Orwell Foundation sponsored the first start-to-finish live reading of George Orwell’s 1984 in the UK on 6 June.

The Orwell Foundation hosted the 12-hour event at the University College London’s Senate House, the inspiration for the book’s The Ministry of Truth. The reading was also live-streamed to libraries and theatres across the UK. The foundation celebrates Orwell’s writing and reporting.

Tuesday’s event included 68 individuals who read from 1984 throughout the day. The readers were invited based on their embodiment of an aspect of Orwell’s values such as giving a voice to the powerless, making difficult freedom of speech decisions, having their writing banned and/or oftentimes taking a witty or controversial stance. These individuals were journalists, academics, public figures, artists members of the public and members of Orwell’s family.

While the participants read from 1984, actors performed parts of the book. Audience members described the experience as “topical,” “immersive” and “unforgettable”.

Director of the Orwell Foundation, Jean Seaton explained: “In the era of ‘post-truth politics’ and when every personal gesture is subject to commercial surveillance and commodified as data, the book has new resonance.”

Click here to watch the full 1984 reading.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1496835496497-78ff0269-5a00-9″ taxonomies=”4479″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Jun 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The truth is in danger. Working with reporters and writers around the world, Index continually hears first-hand stories of the pressures of reporting, and of how journalists are too afraid to write or broadcast because of what might happen next.

In 2016 journalists are high-profile targets. They are no longer the gatekeepers to media coverage and the consequences have been terrible. Their security has been stripped away. Factions such as the Taliban and IS have found their own ways to push out their news, creating and publishing their own “stories” on blogs, YouTube and other social media. They no longer have to speak to journalists to tell their stories to a wider public. This has weakened journalists’ “value”, and the need to protect them. In this our 250th issue, we remember the threats writers faced when our magazine was set up in 1972 and hear from our reporters around the world who have some incredible and frightened stories to tell about pressures on them today.

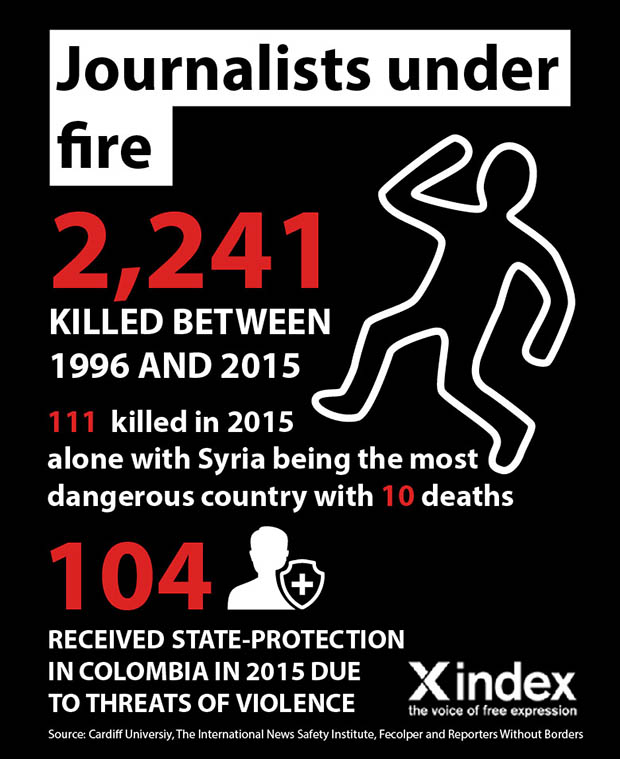

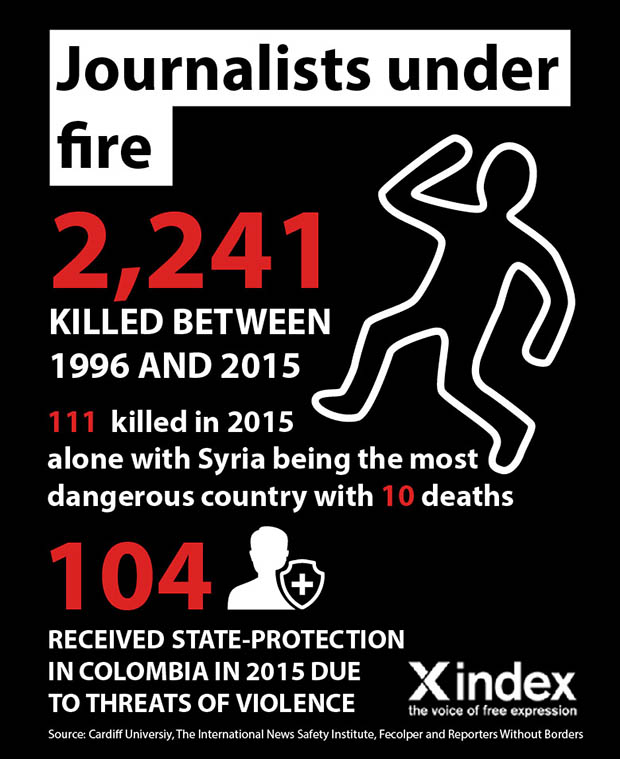

Around 2,241 journalists were killed between 1996 and 2015, according to statistics compiled by Cardiff University and the International News Safety Institute. And in Colombia during 2015 104 journalists were receiving state protection, after being threatened.

In Yemen, considered by the Committee to Protect Journalists to be one of the deadliest countries to report from, only the extremely brave dare to report. And that number is dwindling fast. Our contacts tell us that the pressure on local journalists not to do their job is incredible. Journalists are kidnapped and released at will. Reporters for independent media are monitored. Printed publications have closed down. And most recently 10 journalists were arrested by Houthi militias. In that environment what price the news? The price that many journalists pay is their lives or their freedom. And not just in Yemen.

Syria, Mexico, Colombia, Afghanistan and Iraq, all appear in the top 10 of league tables for danger to journalists. In just the last few weeks National Public Radio’s photojournalist David Gilkey and colleague Zabihullah Tamanna were killed in Afghanistan as they went about their work in collecting information, and researching stories to tell the public what is happening in that war-blasted nation. One of our writers for this issue was a foreign correspondent in Afghanistan in 1990s and remembers how different it was then. Reporters could walk down the street and meet with the Taliban without fearing for their lives. Those days have gone. Christina Lamb, from London’s Sunday Times, tells Index, that it can even be difficult to be seen in a public place now. She was recently asked to move on from a coffee shop because the owners were worried she was drawing attention to the premises just by being there.

Physical violence is not the only way the news is being suppressed. In Eritrea, journalists are being silenced by pressure from one of the most secretive governments in the world. Those that work for state media do so with the knowledge that if they take a step wrong, and write a story that the government doesn’t like, they could be arrested or tortured.

In many countries around the world, journalists have lost their status as observers and now come under direct attack. In the not-too-distant past journalists would be on frontlines, able to report on what was happening, without being directly targeted.

So despite what others have described as “the blizzard of news media” in the world, it is becoming frighteningly difficult to find out what is happening in places where those in power would rather you didn’t know. Governments and armed groups are becoming more sophisticated at manipulating public attitudes, using all the modern conveniences of a connected world. Governments not only try to control journalists, but sometimes do everything to discredit them.

As George Orwell said: “In times of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” Telling the truth is now being viewed by the powerful as a form of protest and rebellion against their strength.

We are living in a historical moment where leaders and their followers see the freedom to report as something that should be smothered, and asphyxiated, held down until it dies.

What we have seen in Syria is a deliberate stifling of news, making conditions impossibly dangerous for international media to cover, making local news media fear for their lives if they cover stories that make some powerful people uncomfortable. The bravest of the brave carry on against all the odds. But the forces against them are ruthless.

As Simon Cottle, Richard Sambrook and Nick Mosdell write in their upcoming book, Reporting Dangerously: Journalist Killings, Intimidation and Security: “The killing of journalists is clearly not only to shock but also to intimidate. As such it has become an effective way for groups and even governments to reduce scrutiny and accountability, and establish the space to pursue non-democratic means.”

In Turkey we are seeing the systematic crushing of the press by a government which appears to hate anyone who says anything it disagrees with, or reports on issues that it would rather were ignored. Journalists are under pressure, and so is the truth.

As our Turkey contributing editor Kaya Genç reports on page 64, many of Turkey’s most respected news outlets are closing down or being forced out of business. Secrets are no longer being aired and criticism is out of fashion. But mobs attacking newspaper buildings is not. Genç also believes that society is shifting and the public is being persuaded that they must pick sides, and that somehow media that publish stories they disagree with should not have a future.

That is not a future we would wish upon the world.

Order your full-colour print copy of our journalism in danger magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London, Home in Manchester, Carlton Books in Glasgow and News from Nowhere in Liverpool as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94291″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533353″][vc_custom_heading text=”Afghanistan in 1978-81″ font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533353|||”][vc_column_text]April 1982

Anthony Hyman looks at the changing fortunes of Afghan intellectuals over the past four or five years.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94251″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533410″][vc_custom_heading text=”Colombia: a new beginning?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533410|||”][vc_column_text]August 1982

Gabriel García Márquez and others who faced brutal government repression following the 1982 election.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93979″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533703″][vc_custom_heading text=”Repression in Iraq and Syria” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533703|||”][vc_column_text]April 1983

An anonymous report from Amnesty point to torture, special courts and hundreds of executions in Iraq and Syria. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Danger in truth: truth in danger” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F05%2Fdanger-in-truth-truth-in-danger%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at why journalists around the world face increasing threats.

In the issue: articles by journalists Lindsey Hilsum and Jean-Paul Marthoz plus Stephen Grey. Special report on dangerous journalism, China’s most famous political cartoonist and the late Henning Mankell on colonialism in Africa.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”76282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/05/danger-in-truth-truth-in-danger/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 May 2015 | News and features, United Kingdom

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

It’s hard not to feel sorry for Abu Haleema. The poor man can’t catch a break. All he wants to do is establish a global caliphate under the harshest possible interpretation of sharia — a caliphate in which, he hopes, he will play a significant role — and yet he is thwarted at every turn.

First the authorities stop him from travelling to Syria to join the Islamic State. And then, to add insult to injury, they take away his internet, like he’s a naughty teenager. It’s a hard knock life for Abu.

And it’s about to get even harder. In the Queen’s Speech, the government announced a new counter-extremism bill which, will essentially make the existences of Abu Haleema and people like him illegal, without actually making them illegal.

How does that work? To quote the BBC: “The legislation will also propose the introduction of banning orders for extremist organisations who use hate speech in public places, but whose activities fall short of proscription.”

This, in essence, is a thought ASBO, a convenient way of stamping out “extremism” without making any serious attempt to test that behaviour against any kind of proper harm principle.

Whether we like it or not, we do have laws on hate speech and incitement to violence in the United Kingdom. We also have the powers to proscribe terrorist organisations.

But these powers are apparently not enough: and so we must create semi-legal sub-strata of behaviour where people can be censored on the basis of us not liking what they say very much.

This is not some plea for accommodation of the views of Abu Haleema and his friends. Let us be very clear here: these are views which are entirely antithetical to the secular liberal democracy we aspire to be.

But that fact is exactly the test of a secular liberal democracy: if we are to imagine free speech as a defining value of democracy (as David Cameron has said he does) then we cannot just choose which free speech we will defend and which we will not (as David Cameron has said he wants to). As commentator Jamie Bartlett has pointed out, free speech is not something that one pledges allegiance to in the abstract while stifling in the practice.

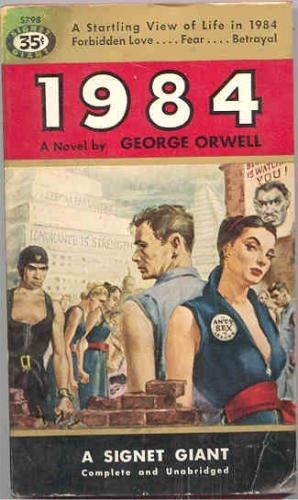

Predictably, we now turn to the life and times of George Orwell for a lesson from history.

In early 1945, a small group of London anarchists found themselves facing prosecution for undermining the war effort — specifically the charge of “causing disaffection among the troops”. Their crime was to criticise basic training, and to suggest that Belgian resistance movements should not hand over weapons to their Allied liberators, but instead retain their arms and set about building workers’ militias which would form a revolutionary force in post-Nazi Europe.

For this, several of the group were jailed, the British authorities of the time not noticing the irony of fighting for freedom in Europe while jailing dissidents at home.

The failure of the state — and the civil liberties movement — to stand for the right to free speech led to the formation of the Freedom Defence Committee.

Most of the supporters of the Freedom Defence Committee, including Orwell, would have had some sympathy with the anarchist position (Orwell had hoped, in the early days of the war, that the training and arming of the Home Guard would lead to a socialist revolution after the Nazis had been defeated. Apart from that, at least one of the accused, Vernon Richards, was a friend of Orwell’s).

But Orwell and his comrades in the Freedom Defence Committee were alert to the fact that one cannot simply defend the freedom of one’s friends. One also had to stand for the rights of communists and even fascists to hold their views. (Before any reader attempts to refer me to Orwell’s supposedly infamous “list” of communists and fellow travellers, supplied to his friend Celia Kirwan at the government’s Information Research Department, let me point out that it was a list compiled as a favour for a friend, not a blacklist: no one on that list was ever arrested, and they pursued their careers and lives unhindered). This led to the FDC taking the position that those with unpopular views – even those who had been (and still were) on the other side in the war, should be given the same justice as everyone else – demanding, for example, proper rights in cases of dismissal from employment when such a concept barely existed for anyone.

Fascists, communists and Islamists aside, there is probably not a single political grouping in Britain today that does not lay some claim to Orwell’s legacy. But as with free speech arguments, all tend to support the side that supports their side: libertarians cling to the anti-surveillance overtones in his work, while ignoring the long-held demands for state intervention on some issues. Conservatives admire the anti-communism, while ignoring the horror at capitalism, tradition, and the class system. Socialists pretend that Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm were anything else apart from scathing attacks on left utopianism.

Orwell was a far from perfect figure, but he did get a lot of things right — the fundamental one being the consistent application of principles on issues of liberty.

It is fashionable to invoke Big Brother whenever governments introduce new surveillance measures, or suggest censorship of extremist views. It is also, generally, silly and hyperbolic. But when faced with an enemy entirely at odds with democracy, as we are with Islamist extremism, it’s worth noting that, as did Orwell and his comrades, it is possible to attack the ideology while standing firm on freedom.

An earlier version of this article stated that a group of London anarchists faced prosecution for suggesting the Belgian resistance movements should not hand over weapons to their German liberators. This has been corrected.

This column was posted on 28 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Jan 2014 | Comment

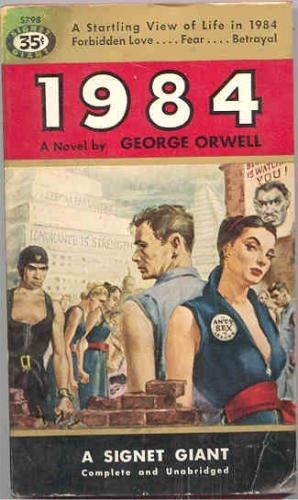

George Orwell died on this day in 1950. This article, from Index on Censorship magazine (volume 42,no 3), looks at one legacy he may not have liked.

Subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine here

The revelation that US intelligence services have allegedly been monitoring everyone in the entire world all the time was good news for the estate of George Orwell, who guard the long-dead author’s copyright jealously.

Sales of his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four rocketed in the United States in June as Americans sought to find out more about the references to phrases such as “Big Brother” and “Orwellian” that littered discussions of the National Security Agency’s PRISM programme.

The Wall Street Journal even went so far as to describe this profoundly bleak novel as “one of the hottest beach reads this summer”. And web editors, hankering after a top ten Google ranking for their articles, quickly commissioned articles on the Orwellian theme.

Meanwhile, news website Business Insider published a plot synopsis that managed to run through the events of the book without describing what the book was about at all. The nadir of this frenzy was reached by an Associated Press correspondent, who wrote of his “Orwellian” experience of being stuck airside at the same Moscow airport as whistleblower Edward Snowden for a few hours (for added awfulness, an editor’s note on the piece suggested that this deliberate exercise in boredom was “surreal”).

Nineteen Eighty-Four (not 1984) has become the one-stop reference for anyone wishing to make a point. CCTV? Orwellian. Smoking ban? Big Brother-style laws. At the height of the British Labour Party’s perceived authoritarianism while in government, web libertarians squealed that “Nineteen Eighty-Four was a warning, not a manual”.

It was neither. It’s a combination of two things: a satire on Stalinism, and an expression of Orwell’s feeling that world war was now set to be the normal state of affairs forever more.

A brief plot summary, just in case you haven’t taken the WSJ’s advice on this summer’s hot read: Nineteen Eighty-Four tells the story of an England ruled by the Party, which professes to follow Ingsoc (English Socialism). Winston Smith, a minor party member, thinks he can question the totalitarian party. He can’t, and is destroyed.

While Orwell was certainly not a pacifist, descriptions of the crushing terror of war, and the fear of war, run through much of his work. In 1944, writing about German V2 rockets in the Tribune, he notes: “[W]hat depresses me about these things is the way they set people off talking about the next war … But if you ask who will be fighting whom when this universally expected war breaks out, you get no clear answer. It is just war in the abstract.”

It’s hard for us to imagine now, but Orwell was writing in a world in which the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was not yet formulated, and where the Soviet Union seemed unstoppable. Orwell had long been sceptical of Soviet socialism, and for his publisher Frederic Warburg Nineteen Eighty-Four represented “a final breach between Orwell and Socialism, not the socialism of equality and human brotherhood which clearly Orwell no longer expects from socialist parties, but the socialism of Marxism and the managerial revolution”. Warburg speculated that the book would be worth “a cool million votes to the Conservative party”.

This is the context in which Nineteen Eighty-Four was written, and the context that should be remembered by anyone who reads it.

But too often it is imagined there is a “lesson” in Nineteen Eighty-Four as, drearily, it seems there must be a lesson in all books. There is not. The brutality of Stalinism was hardly a surprise to anyone by 1949. The surveillance, the spying, the censorship and manipulation of history were nothing new. Orwell was not so much warning that these things could happen as convinced that they would happen more. He offers no way out, no redemption for his characters. If this book were to have a lesson, Winston would prevail in his fight against the Party; or Winston would die in his struggle but inspire others. We would at least get far more detail on the rise of Ingsoc (the supposed secret book Winston is given, The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, goes some way in explaining how the Party rules, but doesn’t really explain why it rules). As it is, we get an appendix on the development of “Newspeak”, the Party’s successful project to destroy language and, by extension, thought. This addition is designed only to assure us that the Ingsoc system still thrives long after Winston has knocked back his last joyless Victory gin.

There is no system in the world today, with the possible exception of North Korea (which has barely changed since it was founded just after Nineteen Eighty-Four was published), that can genuinely be said to be “Orwellian”. That is not to say that authoritarian states do not exist, or that electronic surveillance is not a problem. But to shout “Big Brother” at each moment the state intrudes on private life, or attempts to stifle free speech, is to rob the words, ideas and images created by Orwell of their true meaning – the very thing Orwell’s Ingsoc party sets out to do.

This article was posted on 21 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org