2 Dec 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.04 Winter 2015

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”What can’t people talk about? The latest magazine looks at taboos around the world”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

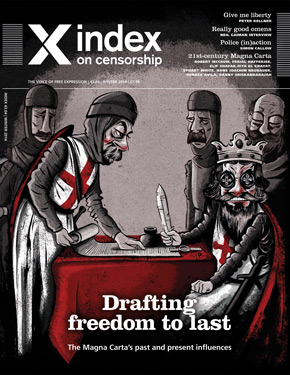

What’s taboo today? It might depend where you live, your culture, your religion, or who you’re talking to. The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores worldwide taboos in all their guises, and why they matter. Comedians Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel look at tackling tricky subjects for laughs; Alastair Campbell explains why we can’t be silent on mental health; and Saudi Arabia’s first female feature-film director Haifaa Al Mansour speaks out on breaking boundaries with conservative audiences.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”60px”][vc_single_image image=”71995″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Plus a crackdown on porn and showing your cleavage in China; growing up in Germany with the ghosts of WW2; what you can and can’t say in Israel and Palestine; and the argument for not editing racism out of old films. As the anniversary of Charlie Hebdo murders approaches, we also have a special section of cartoonists from around the world who have drawn taboos from their homelands – from nudity, atheism and death to domestic violence and necrophilia.

Also in this issue, Mark Frary explores the secret algorithms controlling the news we see, Natasha Joseph interviews the Swaziland editor who took on the king and ended up in prison, and Duncan Tucker speaks to radio journalists who lost their jobs after investigating presidential property deals in Mexico.

And in our culture section, Chilean author Ariel Dorfman looks at the power of music as resistance in an exclusive short story, which is finally seeing the light after 50 years in the pipeline. We have fiction from young writers in Burma tackling changing rules in times of transition, and there’s newly translated poetry written from behind bars in Egypt, amid the continuing crackdown on peaceful protest.

Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year).

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: WHAT’S THE TABOO? ” css=”.vc_custom_1483453507335{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Why breaking down social barriers matters

Stand up to taboos – Shazia Mirza and David Baddiel on how comedy tackles the no-go subjects

The reel world – Nikki Baughan interviews female film directors Susanne Bier and Haifaa Al Mansour, from Denmark and Saudi Arabia

Not just hot air – Kaya Genç goes inside Turkey’s right-wing satire magazine Püff

Slam session – Péter Molnár speaks to fellow Hungarian slam poets about what they can and can’t say

Whereof we cannot speak – Regula Venske on growing up in Germany after WWII

China’s XXX factor – Jemimah Steinfeld investigates a crackdown on porn and cleavage

Pregnant, in danger and scared to speak – Nina Lakhani and Goretti Horgan on abortion laws and social stigma in El Salvador and Ireland

Airbrushing racism – Kunle Olulode explores the problems of erasing racist words from books and films

Why are we whispering? – Alastair Campbell on why discussing mental illness still makes some people uncomfortable

Shouting about sex (workers) – Ian Dunt looks at the debate where everyone wants to silence each other

The history man – Professor Mohammed Dajani Daoudi explains how he has no regrets, despite causing outrage after taking Palestinian students to Auschwitz

Provoking Putin – Oleg Kashin on how new laws are silencing Russians

Quiet zone: a global cartoon special – Featuring taboo-busting illustrations from Bonil, Dave Brown, Osama Eid Hajjaj, Fiestoforo, Ben Jennings, Khalil Rhaman, Martin Rowson, Brian John Spencer, Padrag Srbljanin, Toad and Vilma Vargas

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Reining in power – Natasha Joseph talks to the Swaziland editor who took on the king

Whose world are you watching? – Mark Frary explores the secret algorithms controlling the news we see

Bloggers behind bars – Ismail Einashe interviews Ethiopia’s Zone 9 bloggers

Mexican airwaves – Duncan Tucker speaks to radio journalists who were shut down after investigating presidential property deals

Head to head – Bassey Etim and Tom Slater debate whether website moderators are the new censors

Off the map – Irene Caselli on how some of the poorest people in Buenos Aires fought back against Argentina’s mainstream media

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The rocky road to transition – Ellen Wiles introduces new fiction by young Burmese writers Myay Hmone Lwin and Pandora

Sounds of solidarity – Chilean author Ariel Dorfman presents his short story on the power of music as resistance

Poetry from a prisoner – Omar Hazek shares his verses written in an Egyptian jail and translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view – Index on Censorship’s CEO, Jodie Ginsberg, on the pull between extremism legislation, free speech and terrorism

Index around the world – Josie Timms presents Index’s latest work and events

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

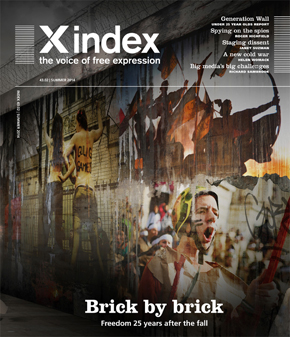

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Max Wind-Cowie on free speech in politics, taken from the winter 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Elections – live! session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

We are often, rightly, concerned about our politicians censoring us. The power of the state, combined with the obvious temptation to quiet criticism, is a constant threat to our freedom to speak. It’s important we watch our rulers closely and are alert to their machinations when it comes to our right to ridicule, attack and examine them. But here in the West, where, with the best will in the world, our politicians are somewhat lacking in the iron rod of tyranny most of the time, I’m beginning to wonder whether we may not have turned the tables on our politicians to the detriment of public discourse.

Let me give you an example. In the UK, once a year the major political parties pack up sticks and spend a week each in a corner of parochial England, or sometimes Scotland. The party conferences bring activists, ministers, lobbyists and journalists together for discussion and debate, or at least, that’s the idea. Inevitably these weird gatherings of Westminster insiders and the party faithful have become more sterilised over the years; the speeches are vetted, the members themselves are discouraged from attending, the husbandly patting of the wife’s stomach after the leader’s speech is expertly choreographed. But this year, all pretence that these events were a chance for the free expression of ideas and opinions was dropped.

Lord Freud, a charming and thoughtful – if politically naïve – Conservative minister in the UK, was caught committing an appalling crime. Asked a question of theoretical policy by an audience member at a fringe meeting, Freud gave an answer. “Yes,” he said, he could understand why enforcing the minimum wage might mean accidentally forcing those with physical and learning difficulties out of the work place. What Freud didn’t know was that he was being covertly recorded. Nor that his words would then be released at the moment of most critical, political damage to him and his party. Or, finally, that his attempt to answer the question put to him would result in the kind of social media outrage that is usually reserved for mass murderers and foreign dictators.

Why? He wasn’t announcing government policy. He was thinking aloud, throwing ideas around in a forum where political and philosophical debate are the name of the game, not drafting legislation. What’s more, the kind of policy upon which he was musing is the kind of policy that just a few short years before disability charities were punting themselves. So why the fuss?

It’s not solely an issue for British politics. Consider the case of Donald Rumsfeld. Now, there’s plenty about which to potentially disagree with the former US secretary of state for defense – from the principles of a just war to the logistics of fighting a successful conflict – but what is he most famous for? Talking about America’s ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, he thought aloud, saying “because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” The response? Derision, accompanied by the sense that in speaking thus Rumsfeld was somehow demonstrating the innate ignorance and stupidity of the administration he served. Never mind that, to me at least, his taxonomy of doubt makes perfect sense – the point is this: when a politician speaks in anything other than the smooth, scripted pap of the media relations machine they are wont to be crucified on a cross of either outrage, mockery or both. Why? Because we don’t allow our politicians to muse any longer. We expect them to present us with well-polished packages of pre-spun, offence-free, fully-formed answers packed with the kind of delusional certainty we now demand of our rulers. Any deviation – be it a “U-turn”, an “I don’t know” or a “maybe” – is punished mercilessly by the media mob and the social media censors that now drive 24-hour news coverage.

Let me be clear about what I don’t mean. I am not upset about “political correctness” – or manners, as those of us with any would call it – and I am not angry that people object to ideas and policies with which they disagree. I am worried that as we close down the avenues for discussion, debate and indeed for dissent if we box our politicians in whenever they try to consider options in public – not by arguing but by howling with outrage and demanding their head – then we will exacerbate two worrying trends in our politics.

First, the consensus will be arrived at in safe spaces, behind closed doors. Politicians will speak only to other politicians until they are certain of themselves and of their “line- to-take”. They will present themselves ever more blandly and ever less honestly to the public and the notion that our ruling class is homogenous, boring and cowardly will grow still further.

Which leads us to a second, interrelated consequence – the rise of the taboo-breaker. Men – and it is, for the most part, men – such as Nigel Farage and Russell Brand in the UK, Beppe Grillo in Italy, Jon Gnarr in Iceland, storm to power on their supposed daringness. They say what other politicians will not say and the relief that they supply to that portion of the population who find the tedium of our politics both unbearable and offensive is palpable. It is only a veneer of radicalism, of course – built often from a hodge-podge of fringe beliefs and personal vanity – but the willingness to break the rules captures the imagination and renders scrutiny impotent. Where there are no ideas to be debated the clown is the most interesting man in the room.

They say we get the politicians we deserve. And when it comes to the twin plaques of modern politics you can see what they mean. On the one hand we sit, fingers hovering over keyboards, ready to express our disgust at the latest “gaffe” from a minister trying to think things through. On the other we complain about how boring, monotonous and uninspiring they all are, so vote for a populist to “make a point”. Who is to blame? We are. It is time to self-censor, to show some self-restraint, and to stop censoring our politicians into oblivion.

© Max Wind-Cowie and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas, featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the winter 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 37.03 Autumn 2008

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by author Conor Gearty, on politics and extremism, taken from the summer 2008 magazine. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Can writers and artists ever be terrorists? session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

I object to the ‘age of terror’ title. My anxiety about this is that it is already putting people like me at a disadvantage. I am forced to work within an assumption, which is shared by all normal, sensible people, that we live in ‘an age of terror’. Therefore the point of view that I am about to put – about the total appropriateness of the criminal law; about the relative security in which we live; about the fact of our being pretty secure in comparison with many previous generations – is deemed to be sort of eccentric, if not obstructive. This language has made impossible my victory in the competition for common sense. So I concede we live in a certain age, with misgivings, but I want to call it an age of counter terror. We live in an age during which it has suited certain elements within the culture to talk up, and reflect in law, a concern with a type of criminal violence that warrants legal form in the shape of counter-terrorism laws.

If you are still concerned about the ‘age of terror’, have a look at the FBI’s compendious analysis of terrorism 2000 to 2005 in the United States. You will find references to the occasional environmental activist who has attacked a tractor; you will find detailed analysis of the very occasional intrusion into animal experiment laboratories by this or that criminal tendency committed to the safeguarding of animals; you will find, in other words, a tremendous amount of space devoted to very little. You will find an organisation that is trying to supply an empirical basis for something without very much conviction. That’s why, frankly, the minister of security [Tony McNulty] says [when I asked if there’s empirical evidence for the decision to increase the length of detention without charge to 42 days]: ‘Honestly, no, I won’t provide an empirical basis,’ rather than attempt, in an increasingly embarrassing way, to deliver one.

This ‘age of terror’ depends on a hypothesis about the future, not about the facts of the present, and it is this that makes it so dangerous. The moment you are manoeuvred into a position where you are forced to debate somebody about civil liberties or human rights on certain imprecise assumptions about the future, which have to be taken on trust, then that is the moment when you have lost the debate. So I am extremely anxious about this.

Now moving on to the substance, the second of the terms we have here in this conference title: ‘free speech’. Well, it’s clear, and the minister reminded us, though I thought he took a reckless point because he said, ‘It would be quite wrong to shout ‘‘fire’’, here.’ Well, the usual, conventional example is that it would be wrong to shout fire in a crowded cinema, of course. And we have to tell the students this (and very few teachers do) – unless, that is, there is a fire! You have this real concern that a lot of students who studied constitutional law go to cinemas and there is a very small fire breaking out and they’re thinking to themselves, ‘Oh my God, but didn’t my professor say ‘‘don’t shout fire?’’ ‘ So a little knowledge can be a very dangerous thing. So I felt like intervening with the minister, but as he said himself, his answers were nearly as long as my questions – so I couldn’t.

Of course there has been control on speech in democratic society, but we are not that interested in that today; we are interested in a different kind of thing about which there is also an extremely long record – control on political speech in a democracy. Now, it is completely wrong to think of democratic countries as not having control on political speech. It has been ever thus. Most recently, and controversially, there are debates about race hate and religious hate, and those are the most obvious recent examples of controls on speech that emanate out of a democratic culture.

An obvious one, which reminds us that so much of this depends on context, is Holocaust denial. The president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, spoke at the centre I direct, the Centre for the Study of Human Rights at the London School of Economics. It was a fairly controversial speech, and he got asked about his controls on the press, and in particular about new laws concerning the control of genocide denial. Of course it was asked by an American student for whom this sort of control is often anathema. His answer was: ‘They seem to have it in Switzerland and it does not cause any trouble; in Germany it does not cause any trouble; and it is not going cause any trouble in my country – because we need it.’ In other words, what the president was saying was that democratic cultures make judgments about what is necessary in their own culture and that this drives a great deal of control, not only of speech, simpliciter, but of political speech as well.

Now, in this country, when we talk about controls on extremism, I would say, we are talking about controls on political points of view that are put without any linkage to violence. That too has been a recurring theme in this society, in the entire democratic era. You might say the democratic era starts in 1929 or in 1919. It could even begin, if you had forgotten about the working class, in 1832. But since its inception, we have had control on political speech – and not just during both wars when it was severe. (In the Second World War, parenthetically, Churchill had to order a review of the magistrates’ cases in which anxious judges were throwing people in jail for causing despondency among the public. There was a fantastic debate in the House of Commons, where Churchill, as prime minister, said something along the lines of: ‘We are fighting for freedom, civil liberties and the rule of law, these magistrates have over interpreted the laws we passed, we have to stop them.’) Apart from the wars, in the 1920s, people of the Communist Party here were convicted of sedition. Their conviction was really of membership to the Communist Party, but sedition was the legal form. In 1934, an Act of Parliament was passed called the Incitement to Disaffection Act, which criminalised attempts to persuade the army of the rightness of the socialist cause. In the 1950s and in the 1960s there were political prosecutions under the official secrets legislation that was designed to tackle extremism – which then took the form of radical-left political speech. We have had it in the entire democratic era – so what’s new?

I’ll come to what’s new about the so-called ‘age of terror’, through the so-called terrorism problem – which was of course originally the Irish problem. There have been some references here to this, this afternoon. Memories seem to be extremely short. The legislation was mentioned in the Q&A with the minister. Throughout the problem of political violence in Northern Ireland, there were frequent examples of journalists being at the foreground of efforts by government to attack the peaceful purveyors of political points of view – and in particular to attack the messengers who covered incidents which were of concern to the government. In 1979, for example, Newsnight was compelled by pressure not to broadcast film it had of an IRA action in Carrickmore. In regards the attack on members of the British Army in West Belfast, there were orders that required the media to return its filming of those events, with a view to facilitating prosecution. There was an ABC news crew, which was headed by Pierre Salinger, which was arrested in Northern Ireland. There were frequent controls on the press. There was, it is said, the punishment of Thames TV, through the non- renewal of its franchise – I don’t know if it is the case – for having the temerity to broadcast Death on the Rock, a report that exposed the events in Gibraltar that led to the death of three members of the IRA. There was, above all, the media ban in 1988. A ban not only, as would have been claimed at the time, of IRA members, who were already prevented from appearing on television or radio as a result of proscription introduced in this country in 1974, but of persons who shared the political objectives of the Provisional IRA.

Now this is the point about chill, which is relevant: with the media ban in place, Mr McNulty, or the equivalent of the day, naturally says ‘We do not intend to destroy free speech; we are sending out signals of support for freedom.’ The reality is, however, that news editors, nervous members of the university computer department, radio talk shows and producers are not scrutinising the media ban, they’re not looking at the Internet – they are thinking there is a law that stops me doing ‘this’, but they are vague and anxious about what the ‘this’ is that they refuse to do. It is back to the magistrates during the Second World War. It is the broadcasting of a pop song, by the Pogues for example; it is the refusal to have an interview with persons pushing for the point of view that the Birmingham Six and Guildford Four have not been lawfully imprisoned because their convictions are unsafe and unsatisfactory. The ‘this’ is actually not the violent extremists being prohibited; the ‘this’ are the people on the wider periphery of the same mission, who find that their ability to enter into the public arena for discussion and debate is being undermined by the drive from within government to address so-called extremism.

Now, the United States is very well versed in this – the country with a strong supposed commitment to free speech that has forced out of existence leftist opinion within the country – so it is not all about law. In the United States, it is called the chill factor. And what we learn from the past – moving now to the contemporary, so-called ‘war on terror’ – is the danger of the chill factor, the danger of fear driving a liberal culture onto the defensive and making normal the repression that flows out of that fear. We had the surfacing of an extreme example when, in the immediate aftermath of the 7 July bombings, the government formed the view that it would be important to prevent the celebration of terrorism actions. You may remember in what is now the Terrorism Act 2006, Section 1, there was a brief period when there was a Terrorism Bill which had the plan of having a schedule of things you could celebrate and a schedule of things you couldn’t. So, if you rather fancied celebrating Cromwell for having chopped off the head of a King, that was okay. There was a period where it looked as though you could celebrate the 1916 Easter Rising, but you couldn’t celebrate anything to do with Islam. You couldn’t celebrate the removal of the Shah of Iran, for example, because it is about power – and the powerful are able to determine what they can celebrate and what they cannot. Now, this was removed, because debate exposed it as absurd, but the ‘power’ point remains.

The powerful have erected their current position usually off the backs of violence – not necessarily their own violence, but the violence of their predecessors – and they can celebrate that violence without fear, because they have the power to control the system. But those who have no power in the culture, those who critique the effect of the exercise of power on them, their rival stories of resistance to oppression, of colonial liberation, are condemned as the celebration of terrorism.

Now, finally, what’s different about this current age of terror, the extremism of today? Well, the IRA problem was one that produced in the end a solution; and it was always understood that there was the possibility of a solution. My real concern about this stuff, about the age of terror, is not the word ‘terror’ but the word ‘age’. It is a new situation from which we cannot remove ourselves. It requires no enemy. If you haven’t recently read George Orwell’s 1984, go back to it and read bits of it with this in mind. The unknown enemy who cannot be named, much less found, who never appears to fight back. We know, yes, there are 16 or 17 terrorist plots in the UK or 20 or 22 we are sometimes told, we don’t know whether it is the same number as last year or whether this has changed. Now, I can’t question the Secret Service’s briefings. For all I know these plots do exist. But there is a driven quality to this – a drive for a re- organisation of our culture, away from the commitment of liberal values and in the direction of the commitment of security, which I think is quite important.

One of the reasons why the 42-day detention period matters so much to me, is because opposition to it is a very strong signal that law should not be made on the basis of undisclosed fears about an uncertain future. And it is a blank cheque to the powerful – to push through everything that they desire off the back of that. I wonder what you thought about Mr McNulty’s response about his proposed objections to an extension to 90-days detention in three years, when a Conservative strongman of some sort or other is home secretary and there is a further push for yet more law? How can Labour oppose such a law? The culture will have shifted, with both of our main parties now in favour of extreme legislation on the basis of future threat. We will have lost something important, something liberal, in our political community.

I know that I haven’t dealt with law, which is also in the title, but it is on this point about the culture that I want to end. Do not look to law to dig you out of this hole if you believe in free speech, if you believe in a democratic culture that involves freedom for the powerless as well as for the powerful. Law usually sides with the powerful; law has always done so in this country, apart from one or two occasions, which are then paraded as evidence of the truth. Exceptions do not make rules; exceptions show the existence of the rules. In the 1930s, all the executive and police repression was upheld; in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s as well; the media ban was upheld in the House of Lords in the late 1980s. The stop and search powers in Section 44 of the Terrorism Act 2000, which the minister acknowledges are being used too broadly, have been upheld by the House of Lords, in a recent case, Gillan v the Metropolitan Police Commissioner. So don’t be misled by avuncular old men being profiled in the liberal press. There are one or two exceptions, but do not rely on law to dig you out of this hole. Rely on political action, rely on generating enough head of steam to preserve our liberal values, so that it becomes common sense – not for Mr McNulty, not for the Mr McNulty of two or three years, when he is trying to rebuild his relationship on the left, but common sense for the McNultys of today, or the Lord Goldsmiths of last year. The culture will be more secure when people, like Churchill during the war, commit to free speech when they are in power and not only when they have left office.

© Conor Gearty and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the summer 2008 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine, with a special report on propaganda and war. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 43.02 Summer 2014

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Jason DaPonte, on privacy on the internet taken from the summer 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Privacy in the digital age session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

“Government may portray itself as the protector of privacy, but it’s the worst enemy of privacy and that’s borne out by the NSA revelations,” web and privacy guru Jeff Jarvis tells Index.

Jarvis, author of Public Parts: How Sharing in the Digital Age Improves the Way We Work and Live argues that this complacency is dangerous and that a debate on “publicness” is needed. Jarvis defines privacy “as an ethic of knowing someone else’s information (and whether sharing it further could harm someone)” and publicness as “an ethic of sharing your own information (and whether doing so could help someone)”.

In his book Public Parts and on his blog, he advocates publicness as an idea, claiming it has a number of personal and societal benefits including improving relationships and collaboration, and building trust.

He says in the United States the government can’t open post without a court order, but a different principle has been applied to electronic communications. “If it’s good enough for the mail, then why isn’t it good enough for email?”

While Jarvis is calling for public discussion on the topic, he’s also concerned about the “techno panic” the issue has sparked. “The internet gives us the power to speak, find and act as a [single] public and I don’t want to see that power lost in this discussion. I don’t want to see us lose a generous society based on sharing. The revolutionaries [in recent global conflicts] have been able to find each other and act, and that’s the power of tech. I hate to see how deeply we pull into our shells,” he says.

The Pew Research Centre predicts that by 2025, the “internet will become like electricity – less visible, yet more deeply embedded in people’s lives for good and ill.” Devices such as Google Glass (which overlays information from the web on to the real world via a pair of lenses in front of your eyes) and internet-connected body monitoring systems like, Nike+ and Fitbit, are all examples of how we are starting to become surrounded by a new generation of constantly connected objects. Using an activity monitor like Nike+ means you are transmitting your location and the path of a jog from your shoes to the web (via a smartphone). While this may not seem like particularly private data, a sliding scale emerges for some when these devices start transmitting biometric data, or using facial recognition to match data with people you meet in the street.

As apps and actions like this become more mainstream, understanding how privacy can be maintained in this environment requires us to remember that the internet is decentralised; it is not like a corporate IT network where one department (or person) can switch the entire thing off through a topdown control system.

The internet is a series of interconnected networks, constantly exchanging and copying data between servers on the network and then on to the next. While data may take usual paths, if one path becomes unavailable or fails, the IP (Internet Protocol) system re-routes the data. This de-centralisation is key to the success and ubiquity of the internet – any device can get on to the network and communicate with any other, as long as it follows very basic communication rules.

This means there is no central command on the internet; there is no Big Brother unless we create one. This de-centralisation may also be the key to protecting privacy as the network becomes further enmeshed in our everyday lives. The other key is common sense. When asked what typical users should do to protect themselves on the internet, Jarvis had this advice: “Don’t be an idiot, and don’t forget that the internet is a lousy place to keep secrets. Always remember that what you put online could get passed around.”

As the internet has come under increasing control by corporations, certain services, particularly on the web, have started to store, and therefore control, huge amounts of data about us. Google, Facebook, Amazon and others are the most obvious because of the sheer volume of data they track about their millions of users, but nearly every commercial website tracks some sort of behavioural data about its users. We’ve allowed corporations to gather this data either because we don’t know it’s happening (as is often the case with cookies that track and save information about our browsing behaviour) or in exchange for better services – free email accounts (Gmail), personalised recommendations (Amazon) or the ability to connect with friends (Facebook).

“A transaction of mutual value isn’t surveillance,” Jarvis argues, referencing Google’s Priority Inbox (which analyses your emails to determine which are “important” based on who you email and the relevance of the subject) as an example. He expands on this explaining that as we look at what is legal in this space we need to be careful to distinguish between how data is gathered and how it is used. “We have to be very, very careful about restricting the gathering of knowledge, careful of regulating what you’re allowed to know. I don’t want to be in a regime where we regulate knowledge.”

Sinister or not, the internet giants and those that aspire to similar commercial success find themselves under continued and increasing pressure from shareholders, marketers and clients to deliver more and more data about you, their customers. This is the big data that is currently being hailed as something of a Holy Grail of business intelligence. Whether we think of it as surveillance or not, we know – at least on some level – that these services have a lot of our information at their disposal (eg the contents of all of our emails, Facebook posts, etc) and we have opted in by accepting terms of service when we sign up to use the service.

“The NSA’s greatest win would be to convince people that privacy doesn’t exist,” says Danny O’Brien, international director of the US-based digital rights campaigners Electronic Frontier Foundation. “Privacy nihilism is the state of believing that: ‘If I’m doing nothing wrong, I have nothing to hide, so it doesn’t matter who’s watching me’.”

This has had an unintended effect of creating what O’Brien describes as “unintentional honeypots” of data that tempt those who want to snoop, be it malicious hackers, other corporations or states. In the past, corporations protected this data from hackers who might try to get credit card numbers (or similar) to carry out theft. However, these “honeypot” operators have realised that while they were always subject to the laws and courts of various countries, they are now also protecting their data from state security agencies. This largely came to light following the alleged hacking of Google’s Gmail by China. Edward Snowden’s revelations about the United States’ NSA and the UK’s GCHQ further proved the extent to which states were carrying out not just targeted snooping, but also mass surveillance on their own and foreign citizens.

To address this issue, many of the corporations have turned on data encryption; technology that protects the data as it is in transit across the nodes (or “hops”) across the internet so that it can only be read by the intended recipient (you can tell if this is on when you see the address bar in your internet browser say “https” instead of “http”). While this costs them more, it also costs security agencies more money and time to try to get past it. So by having it in place, the corporations are creating a form of “passive activism”.

Jarvis thinks this is one of the tools for protecting users’ privacy, and says the task of integrating encryption effectively largely lies with the corporations that are gathering and storing personal information.

“Google thought that once they got [users’ data] into their world it was safe. That’s why the NSA revelations are shocking. It’s getting better now that companies are encrypting as they go,” he said. “It’s become the job of the corporations to protect their customers.”

Encryption can’t solve every problem though. Codes are made to be cracked and encrypted content is only one level of data that governments and others can snoop on.

O’Brien says the way to address this is through tools and systems that take advantage of the decentralised nature of the internet, so we remain in control of our data and don’t rely on third party to store or transfer it for us. The volunteer open-source community has started to create these tools.

Protecting yourself online starts with a common-sense approach. “The internet is a lousy place to keep a secret,” Jarvis says. “Once someone knows your information (online or not), the responsibility of what to do with it lies on them,” says Jarvis. He suggests consumers be more savvy about what they’re signing up to share when they accept terms and conditions, which should be presented in simple language. He also advocates setting privacy on specific messages at the point of sharing (for example, the way you can define exactly who you share with in very specific ways on Google+), rather than blanket terms for privacy.

Understanding how you can protect yourself first requires you to understand what you are trying to protect. There are largely three types of data that can be snooped on: the content of a message or document itself (eg a discussion with a counsellor about specific thoughts of suicide), the metadata about the specific communication (eg simply seeing someone visited a suicide prevention website) and, finally, metadata about the communication itself that has nothing to do with the content (eg the location or device you visited from, what you were looking at before and after, who else you’ve recently contacted).

You can’t simply turn privacy on and off – even Incognito mode on Google’s Chrome browser tells you that you aren’t really fully “private” when you use it. While technologies that use encryption and decentralisation can help protect the first two types of content that can be snooped on (specific content and metadata about the communication), there is little that can be done about the third type of content (the location and behavioural information). This is because networks need to know where you are to connect you with other users and content (even if it’s encrypted). This is particularly true for mobile networks; they simply can’t deliver a call, SMS or email without knowing where your device is.

A number of tools are on the horizon that should help citizens and consumers protect themselves, but many of them don’t feel ready for mainstream use yet and, as Jarvis argues, integrating this technology could be primarily the responsibility of internet corporations.

In protecting yourself, it is important to remember that surveillance existed long before the internet and forms an important part of most nation’s security plans. Governments are, after all, tasked with protecting their citizens and have long carried out spying under certain legal frameworks that protect innocent and average citizens.

O’Brien likens the way electronic surveillance could be controlled to the way we control the military. “We have a military and it fights for us…, which is what surveillance agencies should do. The really important thing we need to do with these organisations is to rein them back so they act like a modern civilised part of our national defence rather than generals gone crazy who could undermine their own society as much as enemies of the state.”

The good news is that the public – and the internet itself – appear to be at a junction. We can choose between a future where we can take advantage of our abilities to self-correct, decentralise power and empower individuals, or one where states and corporations can shackle us with technology. The first option will take hard work; the second would be the result of complacency.

Awareness of how to protect the information put online is important, but in most cases average citizens should not feel that they need to “lock down” with every technical tool available to protect themselves. First and foremost, users that want protection should consider whether the information they’re protecting should be online in the first place and, if they decide to put it online, should ensure they understand how the platform they’re sharing it with protects them.

For those who do want to use technical tools, the EFF recommends using ones that don’t rely on a single commercial third party, favouring those that take advantage of open, de-centralised systems (since the third parties can end up under surveillance themselves). Some of these are listed (see box), most are still in the “created by geeks for use by geeks” status and could be more user-friendly.

Privacy protectors

TOR

This tool uses layers of encryption and routing through a volunteer network to get around censorship and surveillance. Its high status among privacy advocates was enhanced when it was revealed that an NSA presentation had stated that “TOR stinks”. TOR can be difficult to install and there are allegations that simply being a TOR user can arouse government suspicion as it is known to be used by criminals. http://www.torproject.org

OTR

“Off the Record” instant messaging is enabled by this plugin that applies end-to-end encryption to other messaging software. It creates a seamless experience once set up, but requires both users of the conversation to be running the plug-in in order to provide protection. Unfortunately, it doesn’t yet work with the major chat clients, unless they are aggregated into yet another third party piece of software, such as Pidgin or Adium. https://otr.cypherpunks.ca/

Disconnect

This browser plugin tries to put privacy control into your hands by making it clear when internet tracking companies or third parties are trying to watch your behaviour. Its user-friendly inter- face makes it easier to control and understand. Right now, it only works on Chrome and Firefox. http://www.disconnect.me

Silent Circle

This is a solution for encrypting mobile communications – but only works between devices in the “silent circle” – so good for certain types of uses but not yet a mainstream solution, as encryption wouldn’t extend to all calls and messages that users make. Out-of-circle calls are currently only available in North America. https://silentcircle.com

©Jason DaPonte and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the summer 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine, with a special report on propaganda and war. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]