12 Apr 2021 | Ireland, Media Freedom, News and features, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom

As images of serious violence in Northern Ireland beamed around the world last week, many outside the post-conflict society wondered what had gone wrong.

The province, long hailed as one of the best examples of peacebuilding, was for the first time in recent years seeing petrol bombs, vehicle hijackings and masked figures back on the streets on an almost nightly basis.

There is no simple or straightforward explanation for the unrest, which started off in loyalist areas under the guise of peaceful protests.

Those demonstrations surrounded the ‘Irish Sea border’ or Northern Ireland Protocol, part of the Brexit deal that keeps NI aligned with EU rules and treated differently to the rest of the UK.

Controversy over the state prosecutor’s move not to prosecute alleged coronavirus breaches by senior Sinn Fein members at the 2020 funeral of republican and former IRA man Bobby Storey, has also inflamed tensions. The belief in unionist and loyalist circles is that political favouritism played a part in that decision.

Add into the melting pot the recent disruption to loyalist paramilitary crime networks by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), you now have a dangerous mix in a place where anger and frustration has long played out through street violence.

As rioting broke out and escalated across towns and cities, it didn’t take long to spread to interface areas – adding a dangerous sectarian element to the violence.

On 7 April, three days before the 23rd anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, a bus travelling close to a peace divide in the capital of Belfast was hijacked and petrol bombed by loyalist youths.

It sparked scenes not seen on the streets of the loyalist Shankill Road and the Irish Republican stronghold of Lanark Way for some time.

As masonry, fireworks and Molotov cocktails were fired back and forth between hundreds of rival youths, a car rammed into the so-called peace gate that was locked to separate the two communities.

Ironically painted with the words, ‘There Was Never A Good War Or A Bad Peace’, the padlocked steel doors were eventually prised open allowing disorder and destruction to continue into the night, and years of priceless cross-community work put at risk.

News agencies around the world reported on the danger to Northern Ireland’s fragile peace, and the fear that escalating sectarian violence could spiral it back to the dark days of the Troubles, when more than 3,000 people lost their lives.

Sporadic violence, unfortunately, has long been a part of Ulster’s journey from war to peace; a peace that is not perfect but that has achieved the goal of convincing most people that a return to those days cannot, and will not, happen.

Rightfully, international political leaders took notice, expressing concern and calls for calm.

US President Joe Biden said he remained “steadfast” in his support “for a secure and prosperous Northern Ireland in which all communities have a voice and enjoy the gains of the hard-won peace”.

What many do not realise is that the voices he refers to have been under threat for quite some time.

Over the last two years, dozens of journalists in Northern Ireland have been threatened by both loyalist and republican paramilitary groups for their work in exposing criminality and the grip these gangs still have on communities.

Those threats, mainly from loyalists, have escalated in recent times and are having a detrimental impact on press freedom in Northern Ireland.

In May 2020, reporters at both the Sunday World and Sunday Life newspapers received a blanket threat from South East Antrim Ulster Defence Association (UDA), a loyalist criminal cartel that was recently the subject of a high-profile drugs bust.

The gang threatened to take violent action against the journalists, with police informing each of them that intelligence suggests the gangsters may also intimidate their families.

The threats were condemned by major politicians, who in turn then each received death threats from the gang for speaking out in support of the media workers.

In November, the same criminals threatened a journalist with the Belfast Telegraph.

The same month, further loyalist death threats were delivered to the homes of two reporters working for the Sunday World newspaper.

They were informed by police that West Belfast UDA planned to carry out some form of attack on them.

Both had been covering intimidation and threats to those living in a loyalist area and had been named in threatening social media posts prior to being informed of the death threats.

Senior police told one journalist she would be shot, and that the PSNI had received information that the crime gang may try to entrap her.

Since the Northern Ireland Protocol was put in place on 1 January, threats have continued.

Two journalists had their names spray-painted on walls with gun cross hairs in February.

At least one of those was targeted by a paramilitary gang involved in talks with other loyalist groups over discontent over the Irish Sea Border.

Hours before the interface violence broke out in west Belfast last week, press photographer Kevin Scott was attacked as he covered the disorder for the Belfast Telegraph newspaper.

He was pulled to the ground by two masked men who smashed his cameras and threatened, before being told to: “fuck off back to your own area you fenian cunt”.

At the same time 70 miles away, billboards were being erected in Derry by the family of murdered journalist Lyra McKee, appealing for information over her killing.

The 29-year-old was shot dead two years ago by a New IRA gunman as she observed a riot in the city’s Creggan estate. No-one has been convicted over her murder.

As the anniversary of her murder approaches, threats to the safety of journalists have escalated to levels many have not seen in recent times, or even in their entire careers.

The distress and trauma of such threats is compounded by the fact those responsible are continually treated with impunity by the police.

Twenty years ago, Sunday World journalist Martin O’Hagan was assassinated by members of the violent Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF).

The killing gang – who have never been convicted – later released a statement saying the reporter had been murdered for “crimes against the loyalist people”.

Two decades on the same type of language is not only bedecking lampposts across Northern Ireland in the form of anti-Irish Sea Border placards, but is also being used by those with influence in unionism and loyalism.

It is this type of hard rhetoric that has fed into the hostility to media workers here, who have been murdered and attacked as they go about their jobs.

Northern Ireland has paid a very high price for its peace; but what price must it pay to protect press freedom?

27 Nov 2020 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”115674″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This week marked the launch of a sixteen-day UN campaign to eliminate gender-based violence. As part of the global solidarity movement they want to turn the world orange. In the 21st century this campaign should not be necessary, but we see daily examples across the world of how women are being singled out for violence, whether state-sanctioned or by non-state actors or even in people’s homes.

When someone talks about violence towards women it is easy to assume they are talking about domestic violence, after all across the world 243 million women and girls were abused by an intimate partner last year.

Closer to home there were over 200,000 incidents of domestic abuse logged by the police in 2019/20 in England and Wales alone. My friend Jess Phillips, the MP for Birmingham Yardley, every year on International Women’s Day, reads the names of those women who have been murdered in the UK by their partner – this year she read out 108 names.

Jess uses her voice for the women who no longer have one.

But violence against women isn’t only an issue of domestic violence. We’ve seen too many examples where violence against women, whether threats or actual violence, is used as a tool to try and silence them, to ensure that their voices aren’t heard.

Last month a survey published by Plan International found that 59% of women interviewed had been subjected to some form of abuse online. These statistics alone are enough to bring about a chilling effect for women who want to participate in public discourse but it’s compounded when you consider some of the highest profile academics, campaigners and journalists who have been murdered, imprisoned or threatened in recent years:

- Kylie Moore-Gilbert, accused of espionage by the Iranian regime and finally released this week after two years in prison;

- Loujain al-Hathloul, a women’s rights activist in Saudi Arabia who has been imprisoned for the last two years.

- Maria Ressa, the investigative journalist from Rappler, hit with fines and criminal charges for her work;

- Daphne Caruana Galizia, a campaigning Maltese journalist assassinated on 16 October 2017;

- Berta Cáceres, a leading Honduran environmental activist murdered in her home on 2 March 2016.

These women represent untold others, whose stories we simply don’t know – yet. That in itself is heart-breaking.

Our job at Index is to keep shining a spotlight on what is happening across the world, to make sure that as many people’s stories as possible are told. To empower them, to fight with them and to support their families. To make sure that no one is silenced because of the fear of violence.

We were launched nearly 50 years ago – but there is still so much work to do.

For more information on Orange the World see https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/end-violence-against-women[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Apr 2020 | News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Attacks on press freedom in Europe are at serious risk of becoming a new normal, 14 international press freedom groups and journalists’ organisations including Index on Censorship warn today as they launch the 2020 annual report of the Council of Europe Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and the Safety of Journalists. The fresh assault on media freedom amid the Covid-19 pandemic has worsened an already gloomy outlook.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

These threats risk a tipping point in the fight to preserve a free media in Europe. They underscore the report’s urgent wake-up call on Council of Europe member states to act quickly and resolutely to end the assault against press freedom, so that journalists and other media actors can report without fear.

Although the overall response rate by member states to the platform rose slightly to 60 % in 2019, Russia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan – three of the biggest media freedom violators – continue to ignore alerts, together with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

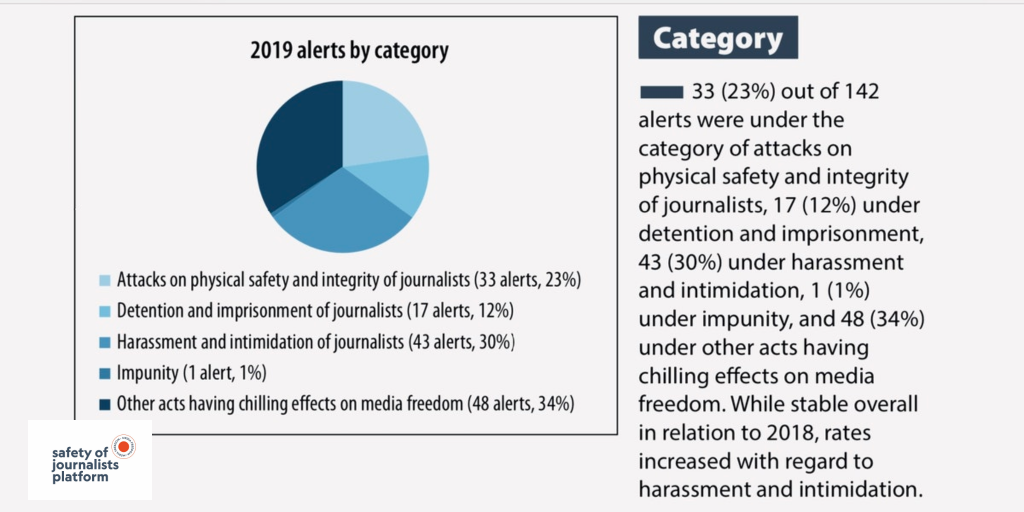

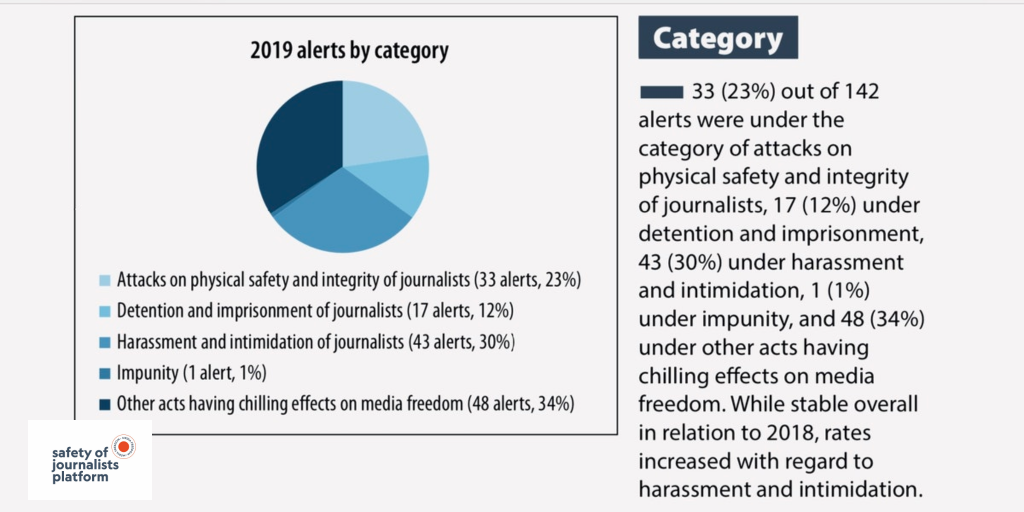

2019 was already an intense and often dangerous battleground for press freedom and freedom of expression in Europe. The platform recorded 142 serious threats to media freedom, including 33 physical attacks against journalists, 17 new cases of detention and imprisonment and 43 cases of harassment and intimidation.

The physical attacks tragically included two killings of journalists: Lyra McKee in Northern Ireland and Vadym Komarov in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the platform officially declared the murders of Daphne Caruana Galizia (2017) in Malta and Martin O’Hagan (2001) in Northern Ireland as impunity cases, highlighting authorities’ failure to bring those responsible to justice. Only Slovakia showed concrete progress in the fight against impunity, indicting the alleged mastermind and four others accused of murdering journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová.

At the end of 2019, the platform recorded 105 cases of journalists behind bars in the Council of Europe region, including 91 in Turkey alone. The situation has not improved in 2020. Despite the acute health threat, Turkey excluded journalists from a mass release of inmates in April 2020, and second-biggest jailer Azerbaijan has made new arrests over critical coverage of the country’s coronavirus response.

2019 saw a clear increase in judicial or administrative harassment against journalists, including meritless SLAPP cases, and spurious and politically motivated legal threats. Prominent examples were the false drug charges filed against Russian investigative journalist Ivan Golunov and the continued imprisonment of journalists in Ukraine’s Russia-controlled Crimea. The Covid-19 crisis has strengthened officials’ tools to harass journalists, with dangerous new “fake news” laws in countries such as Hungary and Russia that threaten journalists with jail for contravening the official line.

Other serious issues identified by 2019 alerts included expanded surveillance measures threatening journalists’ ability to protect their sources, including in France, Poland and Switzerland, as well political attempts to “capture” media through ownership and market manipulation, most conspicuously of all in Hungary. These threats, too, are exacerbated by the actions taken by several governments under the health crisis, which further include arbitrary limitations on independent reporting and on journalists’ access to official information about the pandemic.

Jessica Ní Mhainín, Index’s policy research and advocacy officer, says, “There is a growing pattern of intimidation aimed at silencing journalists in Europe. The situation in Eastern Europe – especially in Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria – is particularly concerning. But the killing of Lyra McKee shows that we cannot take the safety of journalists for granted anywhere – not even in countries that are seen to be safe for journalists. This report provides an opportunity for us all to come to grips with the serious situation that is facing European media and to remind ourselves of the vital role that the media play in holding power to account.”

Index and the other platform partners call for urgent scrutiny of action taken by governments to claim extraordinary powers related to freedom of expression and media freedom under emergency legislation that are not strictly necessary and proportionate in response to the pandemic. Uncontrolled and unlimited state of emergency laws are open to abuse and have already had a severe chilling effect on the ability of the media to report and scrutinise the actions of state authorities.

While the platform welcomes an increased focus on press freedom by European institutions, including both the Council of Europe and European Union institutions, the ongoing crisis demands more urgent and stringent responses to protect media freedom and freedom of expression and information, and to support the financial sustainability of independent professional journalism. In the age of emergency rule, protecting the press as the watchdog of democracy cannot wait.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Apr 2019 | Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, Northern Ireland, Statements, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship has filed an alert with the Council of Europe’s platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists regarding the murder of leading young journalist Lyra McKee in Northern Ireland.

Index condemns the killing in the strongest possible terms and calls on the UK authorities to bring those responsible to justice and on European governments to do more to ensure the safety of journalists.

McKee’s murder follows the murders of three journalists in Council of Europe countries in 2018 — Jan Kuciak, Jamal Khashoggi and Viktoria Marinova. The assassination of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia in Malta in 2017 remains unsolved, with calls for a public inquiry still unmet.

Jodie Ginsberg, Index on Censorship CEO, said: “Lyra McKee’s murder is devastating news. The loss of such promise is heartbreaking. Index will continue to monitor the safety of journalists in the UK and other countries and to campaign for much stronger action to keep journalists safe when they do their work”.

The Council of Europe’s platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists aims to improve the protection of journalists, better address threats and violence against media professionals and foster early warning mechanisms and response capacity within the Council of Europe. Index on Censorship is a platform partner.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]