23 Jun 2022 | News and features, United Kingdom, Volume 51.02 Summer 2022, Volume 51.02 Summer 2022 Extras

Britain’s first LGBT+ Pride march took place 50 years ago, on 1 July 1972. What began as one event in London has since grown into more than 160 Pride events across the UK – from big cities to small towns. Pride has also spread to more than 100 countries, making it one of the most ubiquitous and successful global movements of all time.

How did it all begin?

After the Stonewall uprising in New York in 1969 – when the patrons of gay bars fought back against police harassment – the newly-formed gay liberation movement in the USA decided to organise protests to coincide with the anniversary. The idea spread to the UK, and a group of us in the Gay Liberation Front in London came up with the idea of holding a celebratory and defiant “Gay Pride” march, to challenge queer invisibility and the prevailing view that we should be ashamed of our homosexuality. The ethos of Pride was born.

This was an era of de facto censorship of LGBT+ issues. There was no media coverage of homophobic persecution, no public figures were openly LGBT+ and there were no positive representations of queer people. The only time we appeared in the press was when a gay person was arrested by the police, murdered by queer-bashers, outed by the tabloids, or exposed as a spy, child molester or serial killer.

This is why a Pride march was necessary: to show that we were proud of who we were. But a march was a gamble. Would anyone join us?

Back then, most LGBTs were closeted and dared not reveal themselves publicly, fearing police victimisation. Many aspects of same-sex behaviour were still a crime, given that homosexuality had been only partially decriminalised in 1967. Some were afraid that coming out publicly would result in them being queer-bashed, rejected by family and friends or sacked by homophobic employers.

But, much to our surprise and delight, about 700 people turned out for the first UK Pride in 1972. It was a joyful, carnival-style parade through the streets of London, from Trafalgar Square via Oxford Street to Hyde Park.

We had a political message: LGBT+ liberation. Our banners proclaimed: “Gay is good” and “Gay is angry”. Despite heavy policing and abuse from some members of the public, we made our point.

Buoyed by this first modest success, we had the confidence to organise further Pride marches in the years that followed. They had explicit political demands such as an equal age of consent, an end to police harassment and opposition to lesbian mothers losing custody of their children on the grounds that they were deemed to be unfit parents.

Peter Tatchell in 1974

For most of the 1970s, Pride remained feisty but tiny, with fewer than 3,000 people. However, by the mid-1980s the numbers marching rose to 12,000.

Then we were hit with a triple whammy. First came the moral panic of the Aids pandemic. Dubbed the “gay plague”, it demonised gay and bisexual men as the harbingers of death and destruction. Next the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, attacked the right to be gay at the 1987 Conservative Party conference. And then, in 1988, Section 28 became law, prohibiting the so-called “promotion” of homosexuality by local authorities – the first new homophobic law in Britain for a century.

The LGBT+ community felt under attack – and we were. It brought us together and mobilised a fightback which was reflected in the turnout for Pride in 1988, with 30,000 marchers compared with 15,000 the year before. The march was angry and political, with some people attempting to storm Downing Street.

The first ever Pride in London, 1972. Photo: Jamie Gardiner

From 1988, Pride grew exponentially year on year. By 1997, there were 100,000 people on the march and the post-march festival on Clapham Common was attended by 300,000 revellers. This was the high point of Pride, run by – and for – the community, with strong LGBT+ human rights demands.

Since then, it has been downhill. A takeover by gay businesspeople at the turn of the century rebranded Pride as a “Mardi Gras” party and started charging for the post-march festival. Many people felt that Pride had been hijacked by commercial interests. Numbers plummeted, income crashed and the business consortium walked away.

For the past decade, the event has been run by a private community interest company, Pride in London, under contract and with funding from the mayor of London. It has been accused of being not representative of, or accountable to, the LGBT+ community, and of turning Pride into a depoliticised, overly commercial jamboree.

While some business sponsorship may be necessary to finance Pride, there is unease at the pre-eminence of commercial branding and advertising and the way huge extravagant corporate floats dominate the parade, overshadowing LGBT+ community groups.

Critics also question the participation of the police, arms manufacturers, fossil fuel companies, the Home Office and airlines involved in the deportation of LGBT+ refugees. Is this compatible with the liberation goals that inspired the first Pride?

And there is huge resentment that only 30,000 people are allowed to march in the parade, making Pride in London one of the smallest Prides of any Western capital city. Every year, thousands of people who want to march are turned away. This is against the original premise of Pride: that it should be open to everyone who wants to participate.

Pride in London claims that 1.5 million people attend. But there is no evidence to back this claim and it looks like hype to lure advertisers and sponsors. Even if we generously assume that 100,000 spectators line the route and there are 30,000 people in Trafalgar Square and 50,000 in Soho, plus 30,000 marchers, that’s still only 210,000.

Discontent led to last year’s Reclaim Pride march. It reverted to the roots of Pride, with a grassroots community focus, no corporate sponsors, and demands to ban LGBT+ conversion therapy, reform the Gender Recognition Act and provide a safe haven for LGBT+ refugees fleeing persecution abroad – political issues that have been absent from the official Pride for two decades.

It cost only £1,800 to organise, refuting Pride in London’s claims that Pride cannot exist without corporate funding to the tune of hundreds of thousands of pounds.

This year’s Pride in London parade is on 2 July. The day before, on the 50th anniversary of the UK’s first Pride, a handful of surviving Gay Liberation Front and 1972 Pride veterans will retrace the original route from Trafalgar Square to Hyde Park. Among other things, we’ll be urging the decriminalisation of LGBT+ people worldwide – including in the Commonwealth, where 35 out of the 54 member states still criminalise same-sex relations.

As radical and committed as ever, we pioneers of Pride continue the liberation struggle we began half a century ago. There will be no stopping until homophobia, biphobia and transphobia are history.

This article appears in the forthcoming summer 2022 edition of Index on Censorship. Get ahead of the game and take out a subscription with a 30% discount from Exact Editions using the promo code Battle4Ukraine.

30 Jan 2018 | News and features, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

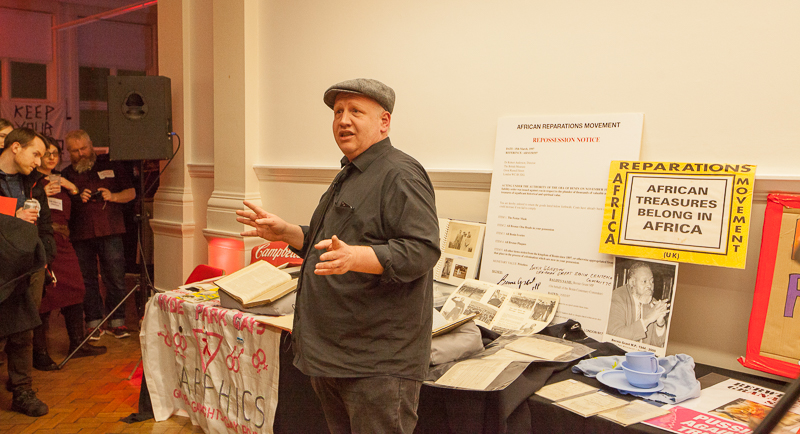

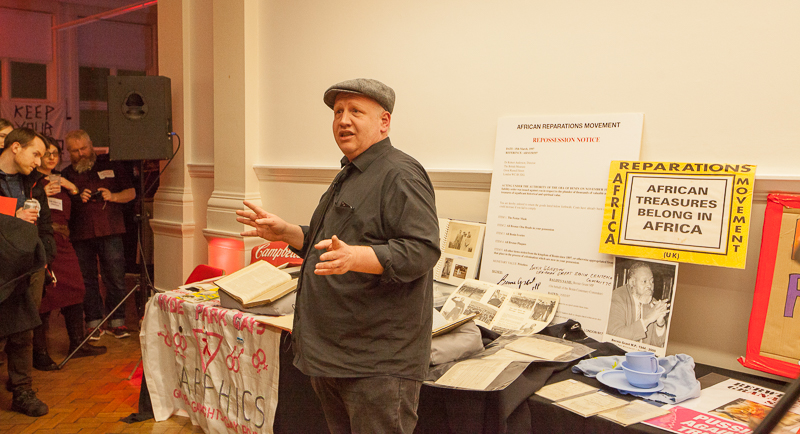

Peter Tatchell discusses the importance of the right to protest. (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Index on Censorship magazine celebrated the launch of its winter 2017 magazine at the Bishopsgate Institute in London with an evening exploring the legacies of iconic protests from 1918 and 1968 to the modern day and reflecting on how today, more than ever, our right to protest is under threat.

Speakers for the evening included human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell, Bishopsgate Institute special collections and archives manager Stefan Dickers and artist Patrick Bullock.

Tatchell discussed the importance of protest for any democracy and the significant anniversaries of protests in 2018 throughout his speech. “This year is a very special year, a very historic year, I think that those protests remind us that protest is vital to democracy,” he said. “It is a litmus test of democracy, it is a litmus of a healthy democracy. Democracies that don’t have protest, there is a problem, in fact, you might even say they aren’t true democracies.”

“With 1968 came the birth of the women’s liberation movement, the mass protests in Czechoslovakia against Russian occupation, and, of course, the huge protests against the American war in Vietnam,” Tatchell added. “Those protests all remind us that protest is vital to democracy.”

Bishopsgate Institute special collections and archives manager Stefan Dickers at the launch of What price protest? (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

This year also marks the centenary of the right to vote for women in Britain. Dickers showcased artefacts the Bishopsgate Institute’s collection of protest memorabilia, including sashes worn by the Suffragettes and tea sets women were given upon leaving prison for activities related to their activism.

Suffragette sashes at the launch of What price protest? (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Attendees included actor Simon Callow, who stressed the importance of protest and freedom of expression: in an interview at the event with Index on Censorship. “There are all sorts of things that people find inconvenient and uncomfortable to themselves, that they don’t wish to hear, but that’s not the point,” he said. “The point is that if some people feel very strongly that certain things are wrong, then they must be allowed to say something.”

Disobedient objects at the launch of What price protest? (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Eastenders actress Ann Mitchell, who also attended the event, said: “There is no question in my opinion, that the darkness in the world at the moment must be protested against. All the advantages we have won as women, as ethnic minorities, are being destroyed, they are being wiped out. Unless we hear voices of protests for that, that will continue.”

The night concluded with a performance by protest choir Raised Voices.

Index magazine’s winter issue on the right to protest features articles from Argentina, England, Turkey, the USA and Belarus. Activist Micah White proposes a novel way for protest to remain relevant. Author and journalist Robert McCrum revisits the Prague Spring to ask whether it is still remembered. Award-winning author Ariel Dorfman’s new short story — Shakespeare, Cervantes and spies — has it all. Anuradha Roy writes that tired of being harassed and treated as second-class citizens, Indian women are taking to the streets.b

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?”][vc_column_text]Through features, interviews and illustrations, the winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the state of protest today, 50 years after 1968, and exposes how it is currently under threat.

With: Ariel Dorfman, Anuradha Roy, Micah White, Richard Ratcliffe[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 May 2017 | Digital Freedom, Middle East and North Africa, News and features, Saudi Arabia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

On 17 May 2017, Index on Censorship joined English Pen, Amnesty International and others in a protest of solidarity outside of the Saudi embassy in London to call for the release of blogger Raif Badawi.

Badawi was detained on 17 June 2012 for creating the website Free Saudi Liberals and “insulting Islam through electronic channels”. Following his arrest, he was eventually sentenced to 10 years in prison and 1000 lashes, the first 50 of which he received in public in January of 2015.

One month away from the five-year anniversary of his arrest, Badawi’s wife, Ensaf Haidar, led dozens of protesters at the embassy. Haidar has said her husband’s mental health is worsening. This makes her pleas with world leaders to aid in the release of Badawi even more urgent. She has recently directly petitioned, among others, the governments of the UK, Germany and her new home of Canada.

Many activists have been protesting at the gates of the embassy for a long time to show their support. Cat Lucas of English Pen said: “We’ve been coming here for almost two and a half years on account of Raif.”

Similarly, human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell said: “We’re here once again to support the campaign to release Raif Badawi and we won’t go away until he is free. Saudi Arabia has a duty to honour their commitments to the human rights law, as their crackdown is doing huge harm worldwide.”

Jo Glanville, director of English Pen, urged the British government to put pressure on Saudi Arabia for the release of Badawi: ,“We are approaching five years since Raif was arrested for doing no more than exercising freedom of expression. We call on the Saudi government to release him immediately and also on the British government to use its very close relationship with the kingdom to ensure he receives the justice he deserves.”

Badawi’s situation is not unique, as Imad Iddine Habib of the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain CEMB noted: “We’re here to call for the immediate release of Raif Badawi who is unjustly in jail for expressing nothing more than his ideas and beliefs. He represents thousands of others who are in prison for similar reasons.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1495116120013-0a48b8dc-fc5e-5″ taxonomies=”7141, 1126, 5711″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

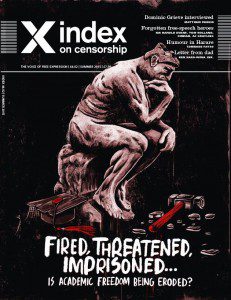

28 Apr 2016 | Academic Freedom, Academic Freedom Reports, Campaigns -- Featured, mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

Academic freedom has been the subject of many debates in recent months. With speakers regularly being no-platformed, and increasing violations of safe space, universities and student unions across the UK have faced harsh criticism.

This growing trend of banning speakers from debates rather than confronting their views head on has led to calls for reforms in university policies in protecting academic freedom and so-called “safe space”.

When human rights activist and ex-Muslim Maryam Namazie was invited by the Atheist, Secularist and Humanist Society (ASH) to speak at Goldsmiths University in December 2015 she faced heckles and interruptions from students who opposed her views.

Throughout Namazie’s talk about blasphemy and apostasy members of Goldsmiths University’s Islamic Society (ISOC) caused a disruption by laughing, shouting out and even switching off her presentation, leading to some students being removed by security.

Namazie spoke to Index about the importance of academic freedom, stating: “Universities have always been hotbeds of dissent and progressive politics. They are places where anything can and should be discussed and debated – where deeply held sensibilities and beliefs can be reviewed, opposed and challenged.

“If you can’t express yourself on a university campus, doing so off-campus is usually even harder. Where academic freedom is restricted, it is a measure of the limits of free speech in society at large.”

Speaking about the Goldsmiths incident, Namazie refuses to be intimidated. She believes those pushing the Islamist narrative want to prevent a counter-narrative on university campuses and therefore it is more important for her to go and speak on any campus she is invited to and to push to be allowed where she is denied access.

“My family fled the Islamic regime of Iran in order to live freer lives. Therefore, it’s especially important for me to speak up, particularly given how many face imprisonment or lose their lives in doing so. I feel I have an added responsibility to speak for those who cannot,” she told Index.

In September 2015 Namazie was invited to speak at Warwick University by the Warwick Atheists, Secularists and Humanists’ Society, but her invitation was withdrawn by the University’s Student Union, who claimed her views would “incite hatred on campus”.

Other activists including Germaine Greer and Julie Bindel have also been silenced on campuses for their controversial views.

Namazie believes no-platforming is having a chilling effect on students’ academic freedom. She told Index: “These policies equate speech with real harm and violence though clearly there is a huge distinction between speech and action. Criticising Islam and Islamism, for example, is not the same as attacking Muslims. Nonetheless, I have been accused of ‘inciting violence’ or ‘inciting discrimination’ against Muslims.”

Human rights activist Peter Tatchell was involved in a dispute in February after National Union of Students’ LGBT representative Fran Cowling, declined to attend an event at the Canterbury Christ Church University at which Tatchell was giving a keynote address and participating on a panel.

He told Index: “Academic freedom is a crucial element of a free and open society. The right to explore, research, articulate, debate and contest ideas — even disagreeable ones — is a democratic hallmark.

“Imposing restrictions is the slippery slope to authoritarianism. As well as diminishing the realm of knowledge and understanding, it reinforces conformism and the status quo; putting a break on dissent and innovation.”

Right2Debate are a student-led movement who are campaigning for an end to censoring and no-platforming in universities by calling for student unions to reform their policies contesting rather than removing divisive and extremist narratives.

The movement, which has 100 student activists across 12 different UK universities and a further 3000 signatures of support, are aiming to have their four-point policy implemented by student unions across the UK. The policy’s outcomes include debate taking place over censorship, uncontested platforms for extremist speakers and transparency in the way the student unions conduct external speaker policy and challenging extremist/divisive narratives.

Haydar Zaki, Quilliam’s Outreach Right2Debate programme coordinator, told Index: “We are in this hostile environment to free speech because of the fruitless terms that have been employed at universities which include safe spaces and duty of care. In reality, these terms are completely open to interpretation, and have led to the chaos we see today whereby speakers are banned (or initially banned) at one university, but then freely allowed in others.

“What student unions and universities need to do is actually start implementing policies that are transparent and uniform — emphasising academic rights and the right to challenge over censorship.”

Bigoted ideas in society need challenging. To do so students require an academic environment that is willing to have open and civil discussions on all types of ideas, including those that could be deemed offensive, believes Benjamin David, an editor at Right2Debate.

Academic freedom is also essential for developing as a society, he told Index: “Academic freedom is important for a variety of reasons, none so pressing than the instrumental value that it has in making advancements in science, law or politics. Such advancements necessitate that the free discussion of opinion is available.”

The summer 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine which focuses on academic freedom. Subscribe here to get your copy.

Professor Chris Frost, former head of journalism at Liverpool John Moores University, agrees. Frost believes academic freedom is important for new ideas to be explored. He told Index: “Academic freedom is critical as it allows academics to investigate matters that may be generally considered socially unacceptable simply because there has been no previous investigation. We cannot expand knowledge and understanding if we don’t challenge socially accepted concepts and seek proof to support our theories. Preventing academic research leads to a stifled society and one that will eventually destroy itself through its own limitations.”

Academic freedom is a regular topic for debate for the Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board, a group of young professionals who meet up for monthly online meetings to discuss current free speech issues. The board spoke to Index about why academic freedom is important to them.

Board member, freelance journalist and race, ethnicity and conflict Masters student, Layli Foroudi, told Index: “Academic freedom is important to me because the purpose of research and study should be to investigate reality, to seek to shed light on some aspect of life, or “truth” — and most importantly, to challenge other people’s truth claims. If there is no academic freedom then there will only be a narrow view of reality that is being purported and left unchallenged.”

Mark Crawford, a postgraduate student specialising in Russian and post-Soviet politics at University College London and current board member, added: “As a historian, it always seemed to me that academic freedom was the closest anyone can really get to ideas breaking down monopolies of power -– hard, scientific investigation can cut through the emotions around nationalism or religion, and afterwards you’re left with truths that however inconvenient are always extremely necessary for new and better narratives to be built.”

This article was updated on 3 May 2016. Corrects to clarify the nature of the dispute over Peter Tatchell’s appearance at Canterbury Christ Church University.

Josie Timms is editorial assistant at Index on Censorship and the first Liverpool John Moores University/Tim Hetherington fellow.

Related:

Why is freedom of speech important?

Worst countries for restrictions on religious freedom