24 Jun 2020 | Index in the Press

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Newly appointed CEO of Index on Censorship Ruth Smeeth talks to host of The Political Podcast Matt Forde about the history of Index on Censorship as we approach our 50th anniversary, how her experiences as Labour MP led her to Index, and the importance of free speech in today’s society.

“This was originally set up for writers and scholars as a place that they could be heard and that other people could celebrate them.”

“The experiences of the last five years [as an MP] made me a different person, it made me genuinely cherish the free press because that meant there was a platform to counter the conspiracy.”

Listen to the full podcast here[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Sep 2019 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Image: Copyright 2011, Newtown Grafitti

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Manchester Central : Exchange 4

Threats to Free Speech

This event will explore the panoply of challenges to freedom of speech in the UK.

Katy Balls, deputy political editor at The Spectator, will chair this event.

Participants include: Index head of advocacy Joy Hyvarinen, Martha Spurrier, director of Liberty; John Whittingdale MP[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

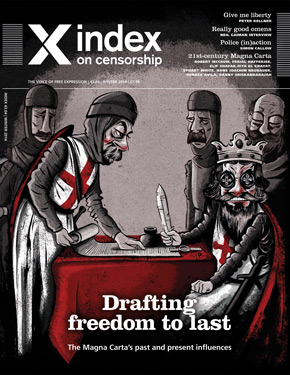

11 Apr 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016 Extras

Kemel Aydogan’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Turkey. Credit: Mehmet Çakici

Hitler was a Shakespeare fan; Stalin feared Hamlet; Othello broke ground in apartheid-era South Africa; and Brazil’s current political crisis can be reflected by Julius Caesar. Across the world different Shakespearean plays have different significance and power. The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, a Shakespeare special to mark the 400th anniversary of his death, takes a global look at the playwright’s influence, explores how censors have dealt with his works and also how performances have been used to tackle subjects that might otherwise have been off limits. Below some of our writers talk about some of the most controversial performances and their consequences.

(For the more on the rest of the magazine, see full contents and subscription details here.)

Kaya Genç on A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream in Turkey

“When Turkish poet Can Yücel translated A Midsummer’s Night Dream, he saw the potential to reflect Turkey’s authoritarian climate in a way that would pass under the radar of the military intelligence’s hardworking censors. Like lovers in Shakespeare’s comedy who are tricked by fairies into falling in love with characters they actually dislike, his adaptation [which was staged in 1981 and led to the arrests of many of the actors] drew on the idea that Turkey’s people were forced by the state to love the authority figures that oppressed them the most. They were subjugated by the military patriarchy, the same way the play’s female and artisan characters were subjugated by Athenian patriarchy.

Kemal Aydoğan, the director of the latest Turkish adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, described the work as ‘one of the most political plays ever written’. For Aydoğan, the scene in which the Amazonian queen Hippolyta is subjugated and taken hostage by the Theseus marks a turning point in the play. ‘That Hermia is not allowed to marry the man she loves but has to wed the man assigned to her by her father is another sign of women’s subjugation by men,’ he said. This, according to Aydoğan, is sadly familiar terrain for Turkey where women are frequently told by male politicians to know their place, keep silent and do as they are told.’ ”

Claire Rigby on Julius Caesar in Brazil

“In a Brazil seething with political intrigue, in which the impeachment proceedings currently facing President Dilma Rousseff are just the most visible tip of a profound turbulence which has gripped the country since her re-election in October 2014, director Roberto Alvim’s 2015 adaptation of Julius Caesar was inspired by a televised presidential debate he saw in the final days of the election campaign, in which centre-left Rousseff faced off against her centre-right opponent Aécio Neves. ‘I watched the debate as it became utterly polarised between Dilma and Aécio, and the famous clash between Mark Antony and Brutus instantly came to mind,’ he said. ‘It was the idea that the same facts can be drawn in such completely different ways by the power of speech: the power of the word to reframe the facts, and its central importance in the political game.’ ”

György Spiró on Richard III in Hungary

“Richard III was staged in Kaposvár, which had Hungary’s very best theatre at the time. This was 1982.

Charges were brought against the production, because the Earl of Richmond wore dark glasses. A few weeks earlier, on 13 December 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared a state of emergency in Poland. For health reasons he wore sunglasses every time he appeared in public.”

Simon Callow on Hamlet under Stalin and the Nazis

“In 1941, Joseph Stalin banned Hamlet. The historian Arthur Mendel wrote: ‘The very idea of showing on the stage a thoughtful, reflective hero who took nothing on faith, who intently scrutinized the life around him in an effort to discover for himself, without outside ‘prompting,’ the reasons for its defects, separating truth from falsehood, the very idea seemed almost ‘criminal’.’ Having Hamlet suppressed must have been a nasty shock for Russians: at least since the times of novelist and short story writer Ivan Turgenev, the Danish Prince had been identified with the Russian soul. Ten years earlier, Adolf Hitler had claimed the play as quintessentially Aryan, and described Nazi Germany as resembling Elizabethan England, in its youthfulness and vitality (unlike the allegedly decadent and moribund British Empire). In his Germany, Hamlet was reimagined as a proto-German warrior. Only weeks after Hitler took power in 1933 an official party publication appeared titled Shakespeare – A Germanic Writer.”

Natasha Joseph on Othello in South Africa

“In 1987, actress and director Janet Suzman decided to stage Othello in her native South Africa, bringing ‘the moor of Venice’ to life at Johannesburg’s iconic Market Theatre. It was just two years since Prime Minister PW Botha had repealed one of apartheid’s most reviled laws, the Immorality Act, which banned sexual relationships between people of different races. Even without the legislation, many white South Africans baulked at the idea of interracial desire. No wonder, then, that Suzman’s production attracted what she has described as ‘millions of bags full of hate letters from people who thought that this was an outrage’.

But in a country famous for sweeping censorship and restrictions on freedom of movement, speech and association, the play was not banned. Why? Because the apartheid government ‘would have been the laughing stock of the world if they had banned Shakespeare’, Suzman told Index on Censorship. ‘Any government would be really embarrassed to ban Shakespeare. The apartheid government was frightened of ridicule. Everyone is frightened of laughter.’ ”

For more articles on Shakespeare’s battle with power around the world, see our latest magazine. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year, with a free trial). Copies are also available in excellent bookshops including at the BFI, Mag Culture and Serpentine Gallery (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon or a digital magazine on exacteditions.com. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, Volume 43.04 Winter 2014

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Max Wind-Cowie on free speech in politics, taken from the winter 2014 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Elections – live! session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

We are often, rightly, concerned about our politicians censoring us. The power of the state, combined with the obvious temptation to quiet criticism, is a constant threat to our freedom to speak. It’s important we watch our rulers closely and are alert to their machinations when it comes to our right to ridicule, attack and examine them. But here in the West, where, with the best will in the world, our politicians are somewhat lacking in the iron rod of tyranny most of the time, I’m beginning to wonder whether we may not have turned the tables on our politicians to the detriment of public discourse.

Let me give you an example. In the UK, once a year the major political parties pack up sticks and spend a week each in a corner of parochial England, or sometimes Scotland. The party conferences bring activists, ministers, lobbyists and journalists together for discussion and debate, or at least, that’s the idea. Inevitably these weird gatherings of Westminster insiders and the party faithful have become more sterilised over the years; the speeches are vetted, the members themselves are discouraged from attending, the husbandly patting of the wife’s stomach after the leader’s speech is expertly choreographed. But this year, all pretence that these events were a chance for the free expression of ideas and opinions was dropped.

Lord Freud, a charming and thoughtful – if politically naïve – Conservative minister in the UK, was caught committing an appalling crime. Asked a question of theoretical policy by an audience member at a fringe meeting, Freud gave an answer. “Yes,” he said, he could understand why enforcing the minimum wage might mean accidentally forcing those with physical and learning difficulties out of the work place. What Freud didn’t know was that he was being covertly recorded. Nor that his words would then be released at the moment of most critical, political damage to him and his party. Or, finally, that his attempt to answer the question put to him would result in the kind of social media outrage that is usually reserved for mass murderers and foreign dictators.

Why? He wasn’t announcing government policy. He was thinking aloud, throwing ideas around in a forum where political and philosophical debate are the name of the game, not drafting legislation. What’s more, the kind of policy upon which he was musing is the kind of policy that just a few short years before disability charities were punting themselves. So why the fuss?

It’s not solely an issue for British politics. Consider the case of Donald Rumsfeld. Now, there’s plenty about which to potentially disagree with the former US secretary of state for defense – from the principles of a just war to the logistics of fighting a successful conflict – but what is he most famous for? Talking about America’s ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, he thought aloud, saying “because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” The response? Derision, accompanied by the sense that in speaking thus Rumsfeld was somehow demonstrating the innate ignorance and stupidity of the administration he served. Never mind that, to me at least, his taxonomy of doubt makes perfect sense – the point is this: when a politician speaks in anything other than the smooth, scripted pap of the media relations machine they are wont to be crucified on a cross of either outrage, mockery or both. Why? Because we don’t allow our politicians to muse any longer. We expect them to present us with well-polished packages of pre-spun, offence-free, fully-formed answers packed with the kind of delusional certainty we now demand of our rulers. Any deviation – be it a “U-turn”, an “I don’t know” or a “maybe” – is punished mercilessly by the media mob and the social media censors that now drive 24-hour news coverage.

Let me be clear about what I don’t mean. I am not upset about “political correctness” – or manners, as those of us with any would call it – and I am not angry that people object to ideas and policies with which they disagree. I am worried that as we close down the avenues for discussion, debate and indeed for dissent if we box our politicians in whenever they try to consider options in public – not by arguing but by howling with outrage and demanding their head – then we will exacerbate two worrying trends in our politics.

First, the consensus will be arrived at in safe spaces, behind closed doors. Politicians will speak only to other politicians until they are certain of themselves and of their “line- to-take”. They will present themselves ever more blandly and ever less honestly to the public and the notion that our ruling class is homogenous, boring and cowardly will grow still further.

Which leads us to a second, interrelated consequence – the rise of the taboo-breaker. Men – and it is, for the most part, men – such as Nigel Farage and Russell Brand in the UK, Beppe Grillo in Italy, Jon Gnarr in Iceland, storm to power on their supposed daringness. They say what other politicians will not say and the relief that they supply to that portion of the population who find the tedium of our politics both unbearable and offensive is palpable. It is only a veneer of radicalism, of course – built often from a hodge-podge of fringe beliefs and personal vanity – but the willingness to break the rules captures the imagination and renders scrutiny impotent. Where there are no ideas to be debated the clown is the most interesting man in the room.

They say we get the politicians we deserve. And when it comes to the twin plaques of modern politics you can see what they mean. On the one hand we sit, fingers hovering over keyboards, ready to express our disgust at the latest “gaffe” from a minister trying to think things through. On the other we complain about how boring, monotonous and uninspiring they all are, so vote for a populist to “make a point”. Who is to blame? We are. It is time to self-censor, to show some self-restraint, and to stop censoring our politicians into oblivion.

© Max Wind-Cowie and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas, featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the winter 2014 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.