13 Aug 2013 | Brazil, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Midia Ninja is a two-year-old media collective in Brazil that has risen to prominence for its reporting during mass demonstrations. (Photo: Midia Ninja)

Holding to their motto of “independent narratives, journalism and action”, a group of young journalists called Mídia Ninja (Ninja Media) used the recent demonstrations in Brazil’s major cities as a stage for their guerilla approach to journalism, using smartphones and social media platforms to reach their audience.

Mídia Ninja was formed two years ago as a hub for independent journalists in Brazil to tell stories with a social twist that traditional media was not covering. Until June this year, the group had 20 people working full time in six of Brazil’s major cities – São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Belo Horizonte, Porto Alegre and Fortaleza.

“We’re interested in showing the ‘B-side’ of things, exploring different narratives”, says Rafael Vilela, a Mídia Ninja member from São Paulo.

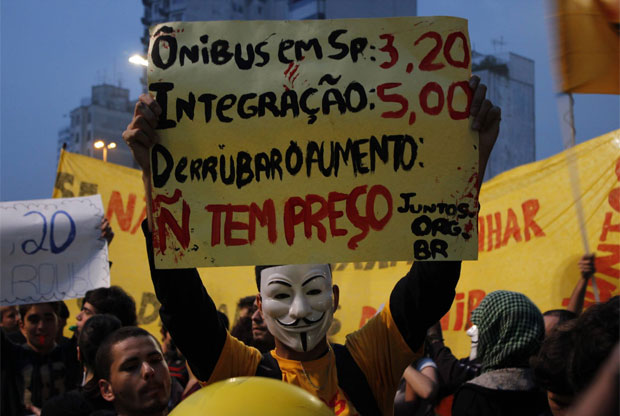

The group came to prominence in June, when they did onsite reporting and live streaming of the mass demonstrations in São Paulo and Rio against rising transport fares that evolved into a movement against the status quo. Being at the core of the action, they were able to shoot and broadcast on their Facebook page some of the most graphic videos of the clashes between protesters and the police.

Using smartphones and cameras, Mídia Ninja’s members mixed with the protesters, and ended up being targeted by the police as well. Three of them were arrested in Rio in July 22nd, during a demonstration against Governor Sergio Cabral.

This demonstration was the point where Mídia Ninja’s work drew the attention of mass audiences. Rede Globo, Brazil’s biggest TV network, showed the group’s interview with protester Bruno Ferreira Telles, who was arrested on the 22 July protest for allegedly throwing incendiary bombs against the police, and was charged with attempted murder.

In his interview, Bruno claimed he was innocent and urged Mídia Ninja to retrieve a video documenting he ran from the police with nothing in his hands – until then, police claimed he carried incendiary bombs when arrested. The video of barehanded Bruno being chased and detained was shown by Globo, and it helped his case. All charges against Bruno have been dropped.

Their work during the demonstrations raised Mídia Ninja’s profile in Brazil, especially through social media. The group’s Facebook page, which now is their main platform, grew from a little over 2,000 fans before June to more than 160,000, and their network of collaborators grew to more than 2,000 people.

“We’re still figuring out how to organize our collaborators work, because it’s so many people”, says Vilela.

The central core of Mídia Ninja is a group of one hundred people gathered in Brazil’s main urban areas. They have no salary: most of their expenses ares paid by Fora do Eixo (Out of the Axis), a network of cultural producers that began by financing independent music festivals in Brazil’s smaller urban areas, and ended up organizing bigger events related to film, music, visual arts and street art.

Most of Mídia Ninja’s members come out of journalism workshops created by Fora do Eixo, and some of them live at São Paulo’s Casa Fora do Eixo, a house where the network’s members can live and work as a community, sharing expenses.

After the street demonstrations became less massive, Mídia Ninja moved forward to cover other social issues like indigenous peoples’ rights. Their goal is to broaden their work.

“Since June we’ve been very focused on the demonstrations, but that’s not the only thing we want to do. There are many things to be written about – in culture, in sports, in daily life”, says Vilela.

Now Mídia Ninja’s main goal is to launch crowdfunding campaigns to support their activities – like launching a website, which is on the way.

Mídia Ninja is not free of criticism. One of their soft spots is precisely their closeness to Fora do Eixo. Many artists accuse Fora do Eixo and its coordinator Pablo Capilé of profiting at their expense, and also of exploiting young activists to work for the network for free.

Some media specialists even dispute if the work Mídia Ninja does should be seen as journalism, because of the way they become participants of the events they were supposed to report.

Digital Journalism professor Marcelo Träsel from PUCRS University in Porto Alegre, for example, says there seems to be a “promiscuous relation” between Mídia Ninja’s journalists and their objects.

“The fact that Mídia Ninja members were arrested alongside demonstrators shows that maybe they are exceeding their role of ‘eyewitness of facts’ that journalists so often claim.”

In the other hand, Träsel concedes that, for not playing the “impartiality card” that became common among big media, Mídia Ninja should be regarded differently than most outlets.

“It’s unfair to judge (Mídia Ninja’s) practices using the ethical code that operates in more traditional newsrooms. The question here is to know to which extent Mídia Ninja’s audience is conscious of the difference between their model and the one from big media, and to recognize the filters this audience uses when they get information from one and from the other”.

This article was originally published on 13 Aug, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org | Index on Censorship: The voice of free expression

24 Jul 2013 | Brazil, Politics and Society

A Brazilian sociologist says he was threatened at gunpoint in Rio de Janeiro last week, after he gave a newspaper interview criticising police action in recent popular demonstrations.

Paulo Baía says he left home around seven o’clock last Friday, 19 July, to take a walk in Flamengo Park, when two armed men wearing balaclavas and sunglasses put him into an unmarked car with tinted windows.

“They told me I should give no more interviews like the one I gave today to Globo and that I shouldn’t say anything else ever again about the Military Police because, if I did, it would be the last interview I would give in my life”, Baía told Globo newspaper.

Globo printed Baía’s interview on the same day he was flash kidnapped. In the article, the sociologist from Rio de Janeiro’s Federal University (UFRJ) analysed groups that acted more violently during demonstrations that happened days before at Leblon, a higher-class area in the south side of Rio. He was critical of police action towards protesters.

“Police saw crimes being committed and did nothing. Police’s message was this: now I’m going to beat everybody up”, he told Globo on the interview.

Baía says he was eventually left at Cinelândia, a public square in Rio, 20 minutes after he was kidnapped. He says guns were not pointed at him, but his kidnappers made them visible the entire time.

The sociologist is wary of alleging that his kidnappers are policemen, as he says that they may be imposters attempting to make a case against the military police.

Later on Friday Baía met Rio State attorney general Marfran Vieira, who said that both the Public Ministry and the Civil Police would check images taken by CCTV cameras at Flamengo Park and Cinelândia.

“This was an attempt to shut down an important voice in the political scene and ends up harming the democratic state based on the rule of law”, said Vieira.

Popular demonstrations that started on early June recently became more violent in Rio, where some protesters have targeted journalists and media outlets, and have also vandalised businesses.

3 Jul 2013 | Americas, Brazil

Brazil’s mass protests represent a new force in the country’s politics. The wave of demonstrations have shaken the country’s lethargic leaders into action, Rafael Spuldar reports

(more…)

17 Jun 2013 | Americas

Sparked by a series of transport fare hikes and official corruption, the ongoing mass protests in Brazil’s cities have been greeted by crackdowns by police. Rafael Spuldar reports on the journalists caught in the crossfire

While large protests are not common events in Brazil, some of the protesters say “the giant has awoken”, meaning that Brazil’s population of 190 million is mobilising to fight corruption and political misconduct.

As many as 15 journalists were injured by police and two were taken into custody during last Thursday’s demonstrations in São Paulo, according to Brazil’s Association of Investigative Journalism (Associação Brasileira de Jornalismo Investigativo, Abraji). The journalists were allegedly beaten, maced or hit by non-lethal rubber bullets covering the protests.

Photographer Sérgio Andrade da Silva from Futura Press agency was hit in the eye by a rubber bullet. Doctors say his chances of full recovery are less than 5 in a hundred.

Reporter Giuliana Valloni from Folha de S.Paulo, Brazil’s biggest daily newspaper, was also hit in the eye by a rubber bullet. She says a policeman shot at her from a 20-meters.

“I wasn’t attacking anyone, I wasn’t cursing at anyone. I was doing my job”, Giuliana told Folha from her hospital bed.

“I saw him aiming at me, but I never thought he would fire, because I had (policemen) aiming at me before that night. You’ll never think that an armed guy in uniform will ever shoot you in the face”, she said.

Folha says that seven of its staff members – including Giuliana – were attacked by policemen at Thursday’s protests.

The harshest clashes between policemen and protesters occurred on Consolação Avenue, in downtown São Paulo. The crowd attempted to march up Consolação to reach Paulista Avenue – the financial center — but riot police blocked their way. More than 200 people were taken into custody.

Videos posted on social media and on YouTube allegedly show police abuse against demonstrators. Some people were targeted with tear gas in their own homes while recording videos of the protests. Other videos show protesters being shot even while they chanted sem violência, sem violência (“no violence, no violence”).

Organizations like Abraji and Brazil’s Press Association (Associação Brasileira de Imprensa, ABI) issued statements denouncing police excesses against media professionals and protesters, and urging the government to take action against them.

“The Union’s Public Ministry cannot be neither passive nor irresponsive before the soulless violence committed in São Paulo’s capital by the State’s security forces, which repeats without originality the repressive practices of the dictatorial regime”, said ABI in its statement, linking the recent events to the repression seen during Brazil’s military rule (1964-1985).

Abraji’s executive director Guilherme Alpendre says acts of violence against journalists during demonstrations are not a common thing, and he believes negative feedback will probably ease down police action and prevent new cases like the ones seen in São Paulo last Thursday.

However, Alpendre points out the fact that attacks by state agents against journalists have increased in the past three years. He cites reporters Mauri König and Rodrigo Neto as examples of that trend: the former wrote about police misconduct in the state of Paraná and had to move to Peru after receiving death threats, while the latter was shot down after denouncing involvement of police members with crime gangs in the state of Minas Gerais.

“I’m not saying all these cases are connected, or that the same method was employed in them, but what we see now is more violence perpetrated by the state against journalists. Those were media professionals identified as such, and they were attacked anyway”, Alpendre told Index on Censorship.

The demonstrations are taking place in many cities — São Paulo, Rio, Brasília, Belo Horizonte, Curitiba, Goiânia and Natal. It started as a national movement against the increase in bus fares, but now its members – mostly young people from leftist parties and students’ organizations – claim their demands are broader.

Protests could be seen during the weekend in federal capital Brasília, Belo Horizonte and Rio de Janeiro, coinciding with the start of the Confederations Cup, a warm-up event to next year’s World Cup, to be hosted in Brazil. Protesters demanded less money be spent on building stadiums and more be applied to education and other social works.

While protests in Belo Horizonte were peaceful, riot police used tear gas and stun grenades against the crowds in Rio and Brasília, where 29 people were arrested.

More demonstrations are scheduled for today. Protests are also being organised in 27 cities around the world in solidarity.

Some scholars have linked demonstrations in Brazil to those seen in Turkey, where mostly young, web-connected people have taken the streets – first to protest against the building of a shopping mall on a park, but later to fight the government.

Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells – one of the world’s most prominent cyberculture theorists – said last week that the demonstrations all over the world found a new way to gather and claim “the city back to the citizens”.

“Before, if people were discontented, the only thing they could do was to go to a mass demonstration organized by parties and unions, which would soon start to negotiate in the name of people. But now the capacity to self-organize is spontaneous. This is new, and this is social networking”, said Castells.