Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

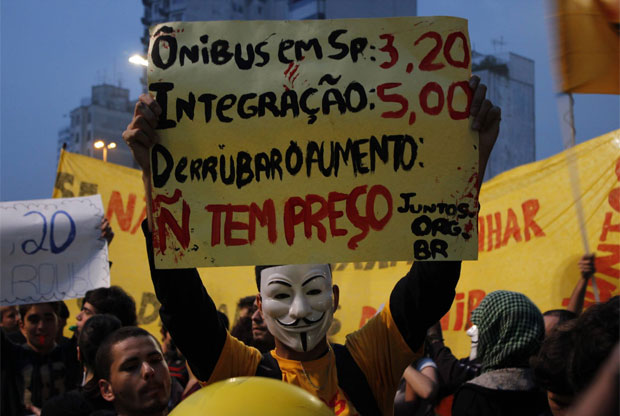

In recent weeks Brazil has seen something unusual – large demonstrations on the streets of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Rafael Spuldar reports on the rise in bus fares that is prompting the protests

Photo: Jimmy Trindade via Facebook

So far this month there have been three major demonstrations in São Paulo and two in Rio. The national movement is coordinated by Movimento Passe Livre , or Free Pass Movement, which is comprised of groups linked to student organizations and leftist parties.

Bus fares increased on 1 June in both cities, jumping from 3 BRL ($1.42) to 3,20 BRL ($1.50) in São Paulo and from 2,75 ($1.30) to 2,95 ($1.40) in Rio. That’s a tough sell in Brazil where the monthly minimum wage of 700 BRL means that a low-wage worker in São Paulo could end up spending a third of their income on transportation.

On Tuesday, as many as 12,000 people marched from São Paulo’s Paulista Avenue area – considered to be the financial heart of South America’s richest city – to the city centre and back. Bus stops and subway stations were smashed during the protest. Riot police fired stun grenades and used tear gas against the protesters.

Some of the demonstrators posted photos and videos on social media denouncing police abuse. They were also critical of media reporting about the events, saying they are portrayed merely as vandals.

Twenty people were taken into custody during the demonstrations. One of them was reporter Leandro Machado from Folha de S.Paulo, Brazil’s biggest daily newspaper. Machado says he was taken by the police – along with a photographer – simply for reporting the arrest of a protester.

Journalist Pedro Nogueira from Portal Aprendiz – an education website – was also arrested while reporting on the protest. Nogueira says he was detained and beaten by the police while trying to help two friends, who were also attacked by policemen. A video posted on YouTube allegedly shows the incident.

In Rio, the latest demonstration took place on Monday evening. Riot police used mace and stun grenades against the protestors after they blocked Avenida Brasil, one of Rio’s main avenues. More than 30 people were taken in custody, many of them young. As in São Paulo, demonstrators used social media to post videos denouncing police excesses against participants.

Protests against bus fares, as well as clashes between demonstrators and the police, took place in other Brazilian capitals like Goiânia and Natal. In Goiânia, the fare rise was reversed by a court ruling.

Violent protests are not a common event in Brazil’s biggest urban areas. In recent days, social media users seem to be divided between supporters and those who denounce the protesters as vandals who damage public property and disrupt traffic.

The latest demonstrations follow successful movements that sought to roll back fare increases in late March in Porto Alegre – capital of southern state of Rio Grande do Sul. There the mayor revoked the rise.

At this week’s protests, demonstrators could be heard chanting “vamos repetir Porto Alegre” (“let’s repeat Porto Alegre”) in São Paulo and Rio.

Rafael Spuldar is a São Paulo-based writer and editor. Follow him on Twitter @spuldar

Brazil’s Federal Police seized a journalist’s equipment – including his computer – during an operation to remove indians from a farm in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. The seizure was decried as illegal by the reporter’s employer, one of the country’s most prominent aid agencies aimed at indigenous peoples, Rafael Spuldar reports.

Ruy Sposati, who works for the Indigenist Missionary Consel (Conselho Indigenista Missionário, CIMI), was covering a land repossession operation carried out by the Federal Police in the city of Sidrolândia on Saturday May 18th.

Ruy Sposati, who works for the Indigenist Missionary Consel (Conselho Indigenista Missionário, CIMI), was covering a land repossession operation carried out by the Federal Police in the city of Sidrolândia on Saturday May 18th.

During the operation, Federal Police official Alcídio de Souza Araújo ordered the seizure of the reporter’s equipment — a laptop computer, an audio recorder and camera lenses.

The confiscation took place without a warrant or any explanation, an act regarded as illegal by the journalist’s employer. When told that Sposati worked for CIMI, Araújo said he had never heard of the organization. A video recording of the action was posted on YouTube.

CIMI is affiliated to the National Conference of Bishops of Brazil. It monitors and aids the country’s many indigenous peoples.

Full Coverage: Brazil | Today on Index: Birthday wishes for Bassel Khartabil | Vietnamese activists appeal sentences | Free expression in the news

Index on Censorship Events

Caught in the web: how free are we online? June 10, 2013

The internet: free open space, wild wild west, or totalitarian state? However you view the web, in today’s world it is bringing both opportunities and threats for free expression. More >>>

CIMI filed complaints against Araújo with the Ministry of Justice, the Federal Public Ministry and the Federal Police’s Magistracy. According to CIMI’s attorney Adelar Cupsinski, this is a case of misuse of authority.

A public statement by CIMI denounced the “militarization” surrounding events related to the indigenous peoples’ struggle for rights in Brazil.

“The institutionalization of this practice is a brutal attempt against a journalist’s professional duty, the social organizations’ freedom and, even more, the democratic and law-ruled relations in our society”, says the statement.

Federal Police says an inquiry about the case is already open. Araújo is expected to present a report justifying his acts.

Brazil loves football – and it loves the game so much it’s hosting next year’s World Cup finals. But a huge number of fans from the state of Paraná are having a very hard time following their team this year because of media restrictions imposed by directors of the local club, Rafael Spuldar reports.

Atlético Paranaense from Curitiba, one of Brazil’s top flight teams and Brazilian champions in 2001, banned press conferences and independent media work during their weekly activities and on match days.

On top of that, no staff member — including players and managers — of Atlético is officially allowed to speak to the media. The club says that radio stations and newspapers should pay for the right to report on the club, along the lines of fees television stations pay to broadcast matches.

On top of that, no staff member — including players and managers — of Atlético is officially allowed to speak to the media. The club says that radio stations and newspapers should pay for the right to report on the club, along the lines of fees television stations pay to broadcast matches.

However, a 2011 federal law forbids football clubs from charging money for radio broadcasts.

The club’s policy is that all information about the team will be funneled through official channels ike the team’s website, online radio and TV. Independent journalists will be limited to background information and off-the-record statements.

It’s a common practice in Brazil’s football industry to have at least two press conferences a week with players and managers and regular media activity on match days. It’s also usual in the country to have people from clubs on sport shows airing on TV and radio, which makes Atlético’s move a rare one in Brazilian football.

“The content we offer is not of a primary importance to the audience, it’s pure entertainment. So we don’t feel obliged to let anyone enter the club’s premises and profit from our business without paying for it, like radio stations do”, says Mauro Holzmann, Atlético’s director of communications and marketing.

“Less than thirty years ago it was OK for televisions to broadcast football matches without paying for it, but now it’s unthinkable to do so. So why don’t the other media pay for it? We know it’s a paradigm shift, but maybe other clubs will do this too”, Holzmann told Index on Censorship.

Broadcasting of matches became another problematic issue. Atlético did not reach an agreement for Paraná’s State Championship with TV rights holders RPC – a local affiliate of national media giant Rede Globo. Because of that, fans were not be able to watch the games unless they bought tickets and went to the pitch.

“This is a complete enclosure that ends up damaging everybody”, says Leonardo Bonasolli, reporter at Gazeta do Povo, Curitiba’s biggest newspaper.

“The club loses exposure at the media, and exposure means more sponsorship money. The press loses the chance of providing a different, independent point of view and, of course, fans also lose because they are not interested only on the team’s monolithic media work”, Bonasolli told Index on Censorship.

Atlético’s chairman Mário Celso Petraglia said the State Championship – which runs from January until early May – is not profitable, so he would not only deny TV broadcasting but would also put the Under-23 team on the pitch, while the main squad would have an extended pre-season in Europe until the start of the Brazilian Championship.

About the media ban, Petraglia said in a rare interview that the club “reached a limit” in its relationship with the press, and that journalists “should be neutral and conduct [their work] in an ethical and moral way”, something he believes does not happen in Paraná.

Petraglia’s disturbed relationship with the press has a long history – it started in the late 1990s, when he was involved in a bribery scheme with referees to fix match results. He was neither convicted nor banned because of the episode.

Atlético first tried to charge money from radios to broadcast its games in 2008. However, a judge ruled the fees were illegal and radio stations have since been given stadium access on match days.

Atlético’s media ban was effectively shut down in early May, during the State Championship finals against historic rivals Coritiba. Rede Globo, which also owns the TV rights of the Brazilian Championship, made a deal with Atlético to allow both matches to be aired. It also closed an agreement for broadcasting the State Championship in 2014 and 2015.

After the game, Atlético’s players gave interviews normally, even to outlets other than Globo, as if there was no ban.

Paraná’s Sports Journalists Association believes Atlético’s attitude towards general media won’t change much, even with the upcoming Brazilian Championship, which draws national attention to all clubs.

“When the Brazilian championship starts, Atlético will be forced to speak to Globo, and they will also feel pressed to hold conferences after matches, because there will be so many journalists from the whole country. But I doubt they will allow other radio or TV stations inside the club during the week, so Globo will do all interviews and share their material to the other outlets”, says the Association’s president, Isaías Bessa.

Local journalists also say the club’s lack of transparency damages Curitiba’s position as one of the host cities of the 2014 World Cup – Atlético’s stadium will a venue. Renovations on the stadium are said to be the most behind schedule of any of the 12 World Cup venues, but independent media was never allowed inside after the works began.

Atlético’s Mauro Holzmann firmly says the stadium will be ready by the end of 2013, like FIFA demands, and blames all delays on “Brazil’s bureaucracy” to deal with public financing.

The Brazilian Congress is considering draft legislation to ease the publication of biographies without prior authorization from the subject, but the move is not without opposition, Rafael Spuldar reports.

The country’s 2002 reformed Civil Code made it mandatory for works of a biographical nature – films, books or otherwise – to have prior authorization from the subject of the work before public release. As a result, most biographies published in Brazil end up being eulogistic to the people they portray.

Critics contend that the current legal framework causes editors to practice self-censorship. “Instead of only taking care of the literary quality of the work, editors end up being busy with judicial problems and carrying out a self-censorship that is harmful to the industry”, says Sônia Machado Jardim, president of Brazil’s National Union of Book (Sindicato Nacional dos Editores de Livros, Snel).

Sônia Machado Jardim supports a change to Brazilian law, which would allow publication of biographies without prior approval of the subject. Photo: www.snel.org.br

Jardim also says that many relatives of people portrayed in biographies try to take advantage of the need of previous approval to demand huge amounts of money, making it impossible to have the works published.

Some controversial cases have become notorious in Brazil. Singer Roberto Carlos, one of the most popular artists in the past 50 years, not only barred in the 2007 circulation of a biography written by Paulo Cesar de Araújo – the copies were already printed and ready to go to the stores – but also banned the publishing of a master’s degree thesis on Jovem Guarda, the musical movement he was part of in the mid 1960s. Before that, in the 1980s, Carlos also prevented the publication of magazine articles about him.

The biography of former footballer and two time World Cup champion Garrincha, who died in 1983, provides another infamous example. Written by journalist Ruy Castro, the book was withdrawn from circulation in 1995 because of a lawsuit filed by Garrincha’s relatives. The author appealed and his work eventually went back on sale.

In 2011, controversies like these led deputy Newton Lima (Workers’ Party) from São Paulo to draft legistlation that changes the Civil Code and annuls the need for prior authorization of biographies from public people – like politicians and media celebrities.

“When people go into public life, they give up part of their right for privacy. Of course one does not want to deprive public people of all their privacy, but it certainly gets diminished”, says the draft bill’s rapporteur in the Congress, deputy Alessandro Molon (Workers’ Party) from Rio de Janeiro.

“It doesn’t mean that the modified law will make it free for anyone to publish anything about anybody. If the person portrayed in a biography feels attacked, he or she can go to the court against the author, and the author himself is still responsible to answer for his work”, says the deputy.

The Chamber of Deputies’ Constitution and Justice Committee passed the draft bill conclusively in early April, which meant it should have gone straight to a Senate vote. However, deputy Marcos Rogério (PDT Party) from the state of Rondônia filed a petition against the proposed bill, making it mandatory that the deputies voted before senators, which slowed down the approval process.

Rogério justified his petition by saying the draft bill’s language left some issues unaddressed.

“What is ‘public dimension’ anyway? It’s a relative concept. Someone can write, for example, a biography about a city counselor either accusing him or promoting him electorally. It can be used for good or for evil. Constitution protects both freedom of expression and privacy”, the deputy said during a Constitution and Justice Committee debate.

Molon regrets this reaction to the draft bill. “While this bill is not voted by the deputies, it cannot go on, and now we depend on the Chamber of Deputies’ speaker’s good will to put it on the voting schedule”, he says. Marcos Rogério could not be reached by Index on Censorship to comment about this subject.

Aside from the new biographies bill, a group of publishers filed a direct action of unconstitutionality with the supreme federal court in July 2012. In their filing, the book firms argue that the Civil Code clause governing prior authorization generates censorship, which is prohibited in Brazil.

Opinions of the suit are to be issued by Brazil’s Solicitor-General Luis Inácio Adams and Attorney-General Roberto Gurgel. Minister Carmem Lúcia is responsible for ruling about the case in the federal supreme court. There is no deadline for the opinions or the court’s ruling.

“When you have a restriction for publishing stories about personalities, the preservation of history’s knowledge is lost. It’s a higher issue than looking for profit”, says Snel’s Sônia Jardim.

“After so many years of fighting to reestablish democracy and freedom of expression in our country, we cannot allow censorship to put its clutches over artistic works ever again”.