1 Nov 2013 | News and features, United Kingdom

State control of the press is hot topic. On Wednesday, Queen Elizabeth signed off a Royal Charter which gives politicians a hand in newspaper regulation. This come after David Cameron criticised the Guardian’s reporting on mass surveillance, saying “If they don’t demonstrate some social responsibility it will be very difficult for government to stand back and not to act”.

But what does state control of the press really look like? Here are 10 countries where the government keeps a tight grip on newspapers.

Bahrain

Press freedom ranking: 165

The tiny gulf kingdom in 2002 passed a very restrictive press law. While it was scaled back somewhat in 2008, it still stipulates that journalists can be imprisoned up to five years for criticising the king or Islam, calling for a change of government and undermining state security. Journalists can be fined heavily for publishing and circulating unlicensed publications, among other things. Newspapers can also be suspended and have their licenses revoked if its ‘policies contravene the national interest.’

Belarus

Press freedom ranking: 157

In 2009 the country known as Europe’s last dictatorship passed the Law on Mass Media, which placed online media under state regulation. It demanded registration of all online media, as well as re-registration of existing outlets. The state has the power to suspend and close both non-registered and registered media, and media with a foreign capital share of more than a third can’t get a registration at all. Foreign publications require special permits to be distributed, and foreign correspondents need official accreditation.

China

Press freedom ranking: 173

The country has a General Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television and an army official censors dedicated to keeping the media in check. Through vaguely worded regulation, they ensure that the media promotes and toes the party line and stays clear of controversial topics like Tibet. A number of journalists have also been imprisoned under legislation on “revealing state secrets” and “inciting subversion.”

Ecuador

Press freedom ranking: 119

In 2011 President Rafael Correa won a national referendum to, among other things, create a “government controlled media oversight body”. In July this year a law was passed giving the state editorial control and the power to impose sanctions on media, in order to stop the press “smearing people’s names”. It also restricted the number of licences will be given to private media to a third.

Eritrea

Press freedom ranking: 179

All media in the country is state owned, as President Isaias Afwerki has said independent media is incompatible with Eritrean culture. Reporting that challenge the authorities are strictly prohibited. Despite this, the 1996 Press Proclamation Law is still in place. It stipulates that all journalists and newspapers be licensed and subject to pre-publication approval.

Hungary

Press freedom ranking: 56

Hungary’s restrictive press legislation came into force in 2011. The country’s media outlets are forced to register with the National Media and Infocommunications Authority, which has the power to revoke publication licences. The Media Council, appointed by a parliament dominated by the ruling Fidesz party, can also close media outlets and impose heavy fines.

Saudi Arabia

Press freedom ranking: 163

Britain isn’t the only country to tighten control of the press through royal means. In 2011 King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia amended the media law by royal decree. Any reports deemed to contradict Sharia Law, criticise the government, the grand mufti or the Council of Senior Religious Scholars, or threaten state security, public order or national interest, are banned. Publishing this could lead to fines and closures.

Uzbekistan

Press freedom ranking: 164

The Law on Mass Media demands any outlet has to receive a registration certificate before being allowed to publish. The media is banned from “forcible changing of the existing constitutional order”, and journalists can be punished for “interference in internal affairs” and “insulting the dignity of citizens”. Foreign journalists have to be accredited with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Vietnam

Press freedom ranking: 172

The 1999 Law on Media bans journalists from “inciting the people to rebel against the State of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and damage the unification of the people”. A 2006 decree also put in place fines for journalists that deny “revolutionary achievements” and spread “harmful” information. Journalists can also be forced to pay damages to those “harmed by press articles”, regardless of whether the article in question is accurate or not.

Zimbabwe

Press freedom ranking: 133

The country’s Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act gives the government direct regulatory power over the press through the Media and Information Council. All media outlets and journalists have to register with an obtain accreditation from the MIC. The country also has a number of privacy and security laws that double up as press regulation, The Official Secrets Act and the Public Order and Security Act.

This article was originally posted on 1 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org.

31 Oct 2013 | News and features, United Kingdom

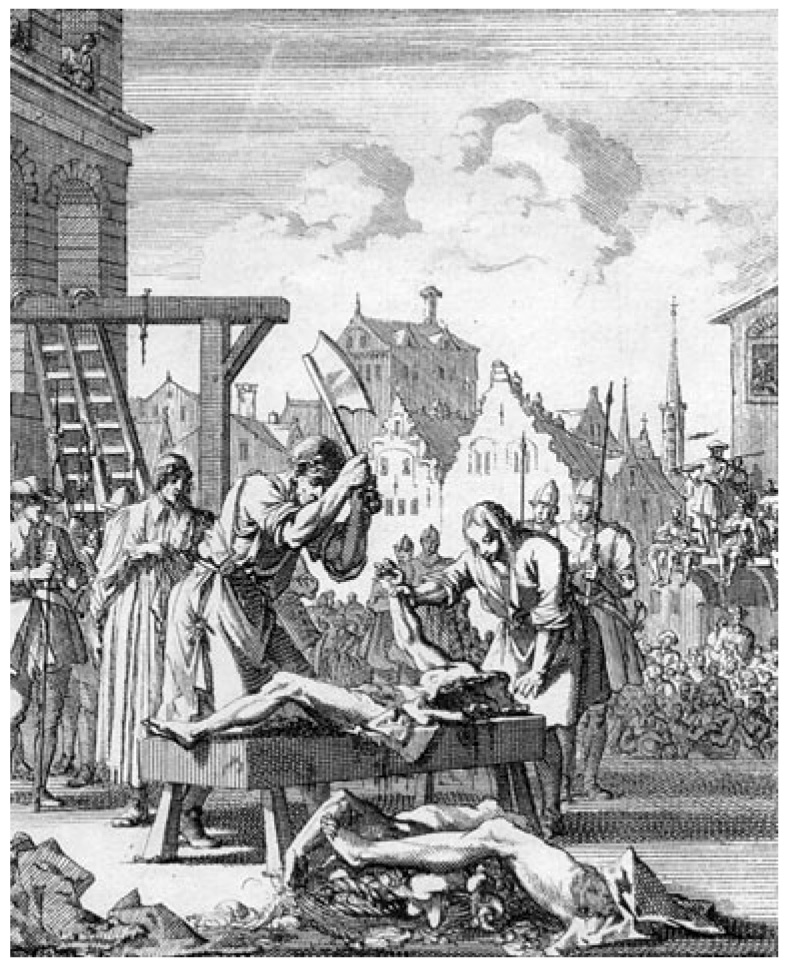

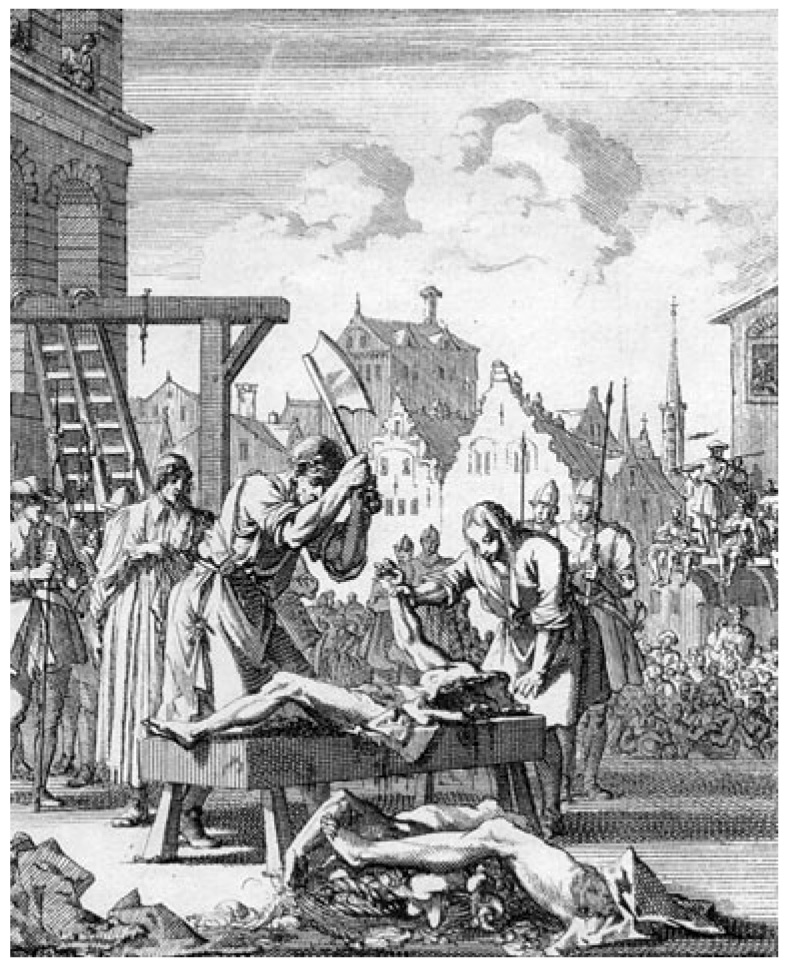

As the royal charter on press regulation was approved by Queen Elizabeth II, Index on Censorship takes a look at crime and punishment the last time the state controlled the press.

The Licensing Order 1643 censored the press by introducing pre-publication licensing, registration of all printing materials with the names of author, printer and publisher, the seizing and destruction of any books that may be deemed offensive to the government, and the arrests and imprisonments of any offensive writers, printers and publishers. Parliament failed to renew the Act in 1695 but what other laws were imposed on Britain’s at the beginning of the 17th century?

- Capital punishments for crimes including treason, piracy, forgery and arson in the Royal Dockyards still existed. What form of capital punishment one received depended on their social background.

- Beheading, which was not abolished until 1747, was normally reserved for those born into nobility.

- Being hung, drawn and quartered was the other more popular option; convicts were driven to the place of execution, hanged, and then whilst still alive (and sometimes conscious) had their stomachs cut open and their entrails drawn out.

- Women found guilty of treason or the murder of their husbands faced the prospect of being burned alive. But don’t worry; the executioner would often strangle the culprit before lighting the match.

- The execution of witches was still legal in England at the time. Unlike in other parts of Europe, those suspected of witchcraft in England were hanged for their crimes as opposed to burnt at the stake. The last execution of a witch was in in 1682, when Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susanna Edwards were executed at Exeter.

- Hollywood movies often depict criminals easily getting away with murder- it was even easier in 1695. Royal Pardons were still dished out for even the most heinous of crimes if the King knew the defendant or felt sympathy towards them. Women had it even easier, often ‘pleading the belly’ that they were with child, omitting them from any punishment until they gave birth. By then their sentencing was often forgotten about.

- Those who had been pardoned were then branded with a letter representing their crime on their thumb preventing them from being let off the hook more than once. For a short time this brand was scorched onto the face but as ex-convicts found they were increasingly unemployable the brand was moved back to the thumb.

- Those who committed petty crimes, including theft and felon, were sentenced depending on their social status, age, sex, and personality. Punishments ranged from imprisonment and committal to a house of correction, where hard labour was often inflicted, to public whipping and time spent in the stocks.

- As the use of the death penalty began to dwindle out at the end of the 17th century a new form of punishment was needed- many criminals soon found themselves transported to Australia.

- Suicide was still illegal in England at the time. Those found to have committed ‘self-murder’ were denied a Christian burial.

- Other laws of the time included a £2 fine for swearing (a lot of money in those times), the requirement of all Englishmen aged 17-60 to keep a longbow for regular archery practice and that all belonged to the Church of England.

This article was originally posted on 31 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org.

8 Oct 2013 | Campaigns, Media Freedom

In response to reports that the UK newspaper industry’s Royal Charter proposal will be rejected tomorrow, Index on Censorship Chief Executive Kirsty Hughes said today:

Unconfirmed reports that the Privy Council will reject the newspaper industry’s royal charter proposal should not mean that the political party proposal for a regulator will be waved through. A truly independent self regulator should not be created by politicians. Now is the time to open transparent discussions with the aim of creating genuine independent self-regulation that will ensure the protection of free speech in the UK.”

Since the start of the Leveson Inquiry into UK press standards, Index has warned that there should be no political interference in determining the characteristics or establishment of a press regulator. Establishing press regulation by Royal Charter could allow politicians to meddle in press regulation and threaten media freedom in the UK.

21 Mar 2013 | News and features, United Kingdom

In response to this week’s deal on press regulation, Index on Censorship chief executive Kirsty Hughes said:

“Index is against the introduction of a Royal Charter that determines the details of establishing a press regulator in the UK — the involvement of politicians undermines the fundamental principle that the press holds politicians to account. Politicians have now stepped in as ringmaster and our democracy is tarnished as a result.”

She also said:

“The fact that this requirement is now being applied to all Royal Charters is a rushed and fudged attempt to pretend this is not just a press law; it resembles precisely the kind of political manoeuvring we see in Hungary today – where the government is amending its own constitution through a parliamentary vote undermining key principles of their democracy.

In spite of David Cameron’s claims, there can be no doubt that what has been established is statutory underpinning of the press regulator. This introduces a layer of political control that is extremely undesirable. On this sad day, Britain has abandoned a democratic principle.

But beyond that, the Royal Charter’s loose definition of a ‘relevant publisher’ as a ‘website containing news-related material’ means blogs could be regulated under this new law as well. This will undoubtedly have a chilling effect on everyday people’s web use.

Bloggers could find themselves subject to exemplary damages in court, due to the fact that they were not part of a regulator that was not intended for them in the first place. This mess of legislation has been thrown together with alarming haste: there’s little doubt we’ll repent for a while to come.”

In addition to issues over damages, there have been further problems raised about apologies. Index’s News Editor Padraig Reidy said:

“There are also concerns about the proposed regulator’s power to “direct” the placement of apologies.

Again, this is “Leveson compliant” — the Lord Justice himself stated “The power to direct the nature, extent and placement of apologies should lie with the Board”.

This is also really problematic, suggesting as it does that a Quango can determine what is and isn’t published in newspapers, and where. This may seem angel-on-pinhead stuff, but there is a world of difference between “direct” and “require”. While apologies may be desirable, it’s simply not safe to give an external power with state underpinning the power to tell editors what to put in papers. Forced publication is a sinister perversion of free expression, and has no place in the British press or anywhere else.”

Read our analysis of the Leveson Inquiry report’s recommendations here.