4 Dec 2015 | Asia and Pacific, Japan, mobile, News and features

David Kaye, UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression

The UN’s principal global monitor of freedom of expression, David Kaye, was due to visit Japan between 1 and 8 December. In mid-November, the Japanese government cancelled the trip.

Kaye said of the cancellation: “The Japanese government indicated that relevant interlocutors would be preoccupied with the budget process. That was disappointing to hear, particularly since we had been organising a broad set of meetings with officials, civil society, academic experts, journalists and others.”

During the visit, Kaye planned to address basic aspects of freedom of expression, including the public’s right to access information, the freedom and protection of independent media, online rights and restrictions on marginalised communities.

He told Index: “We would have highlighted what appear to be some very positive aspects of the freedoms Japanese people enjoy online, for instance, and we would have also raised questions about the Act on Specially Designated Secrets and concerns we’ve been seeing related to pressures on the media.”

The Act on Specially Designated Secrets was implemented in 2013, offering protection to state secrets and tightening penalties on leaking intelligence. The Human Rights Committee has expressed concerns about the act, stating it contained a “vague and broad definition of the matters that can be classified as secret and general preconditions for classification and sets high criminal penalties that could generate a chilling effect on the activities of journalists and human rights defenders”.

“We have studied the Act and wanted to ask officials about the interpretation of some provisions and implementation of the Act overall,” Kaye said. “For instance, we have heard numerous concerns about the way in which the Act may implicate the public’s access to information, the way in which it may punish whistleblowers, the barriers it may set up to a free media seeking information of public interest.”

Had the visit gone ahead, Kaye said he would have come with questions, addressed them to Japanese officials and non-government actors, and the UN would have published the findings.

The cancellation of the visit does raise concerns over Japan’s commitment to freedom of expression, but Kaye remains optimistic. “My hope is that the Japanese government is indeed committed and will reschedule the visit at the earliest opportunity, rather than late 2016, as they have suggested.”

22 Jul 2015 | Middle East and North Africa, mobile, Morocco, News and features

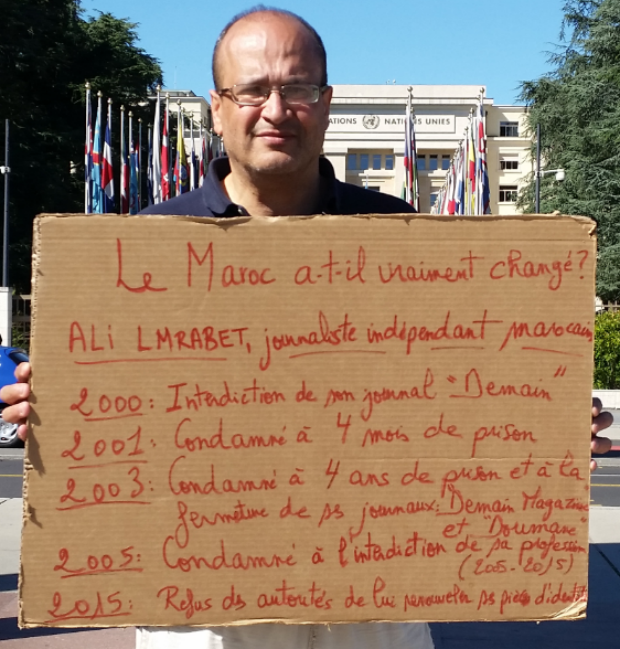

Outside the United Nations building in Geneva, Switzerland, Ali Lmrabet is in his 28th day of a hunger strike. The journalist and satirist is protesting what he sees as the latest bid from his country Morocco to stop him from doing his job.

In a period spanning over a decade, Lmrabet, who was the editor of two satirical publications, has continuously been targeted by Moroccan authorities. In 2003, he was jailed for reporting on personal and financial affairs of Morocco’s King Mohammed VI. His magazine Demain was banned. Though initially handed down a three-year sentence, Lmrabet was released after six months. But his troubles were far from from over: in 2005, he was banned from practising journalism in his home country for ten years, over comments made about the dispute in Western Sahara between Morocco and the Algerian-backed Polisario Front.

Now authorities are seemingly using bureaucracy as a tool to try and silence Lmrabet again. As his ban expired in April this year, he returned to Morocco with the aim of relaunching Demain. But there he was denied a residency permit, without which he is unable to set up the magazine. In a further complication, he also needs the residence permit to renew his passport. When this expired on 24 June, Lmrabet, who was in Geneva to participate in a session of the UN Human Rights Council, decided to start a hunger strike.

“He is very tired,” his partner Laura Feliu told Index on Censorship in a phone interview. She explained how the heat in Geneva has played a part in leaving Lmrabet drained of energy, and while he hasn’t had any serious health problems, he is experiencing sensations of seasickness.

Lmrabet’s protest takes place outside the UN offices, though a heatwave forced him to move inside on Sunday. He sleeps in a Protestant church near the centre of the city. Subsisting on water and some sugar and salt, he has lost at least seven kilograms since the start of the strike.

“He started a hunger strike to protest because he has been denied the right to work as a journalist,” Feliu explained. But in addition to having his free expression and press freedom curtailed, he also has another problem, she adds: “He is denied his right to an identity.”

Lmrabet has support in his country. Some 100 well-known Moroccans from the worlds of media, human rights and academia have signed a petition to the government calling on him to be allowed to renew his documents and continue his work in journalism. Independent and prominent human rights organisations in Morocco are also backing him, according to Feliu.

The response from Moroccan authorities, meanwhile, has so far been unsympathetic. The country’s UN ambassador Mohamed Aujjar has urged Lmrabet to contest what he labelled an “administrative decision” in Morocco, telling AFP that “you don’t get your papers by staging a hunger strike”. Lmrabet, on his part, is unwilling to risk being stranded in Morocco without papers and the ability to work or leave the country. “No one trusts the judical system in Morocco,” he said.

Feliu says it’s difficult to know what the outcome will be, but that Lmrabet is convinced this is the only way to protest. And he remains hopeful.

“He is very convinced of his fight. He is very convinced of his cause. He says that he has the moral to do it.”

Join us 30 July at Stand Up for Satire, a fundraiser in support of Index on Censorship.

This article was posted on 21 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

17 Jun 2014 | Campaigns, Statements, United Nations

An international coalition of more than 200 organisations welcomes the inclusion of targets for capable institutions, media freedom, and access to information by the United Nations member states now participating in the post-2015 development agenda dialogue.

The inclusion of targets on freedom of expression and access to information will help build stronger media and civil society institutions to closely and independently monitor all post-2015 development commitments.

The Open Working Group proposed on June 2, 2014, that the Sustainable Development Goal No. 16 to “achieve peaceful and inclusive societies, rule of law, effective and capable institutions” include sub-goals to “improve public access to information and government data” and “promote freedom of media, association and speech.”

UNESCO and the Global Forum for Media Development convened representatives of this coalition to consider how to strengthen these welcome initiatives and submit for the consideration of member states proposed language and indicators for the text now being discussed by the Open Working Group.

Our proposal is consistent with the criteria that are guiding the efforts to reach consensus on the post-2015 global development agenda, including the Sustainable Development Goals. We urge the continued inclusion of sub-goals 16.14 and 16.17, and we propose below several specific, measurable indicators to achieve these objectives by 2030.

UN Precedents:

- Even before the signing of the 1948 Universal Declaration on Human Rights, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution declaring freedom of expression “a fundamental human right…and the touchstone of all the freedoms to which the United Nations is consecrated.”

- In 1976, after a sufficient number of nations had ratified these instruments and associated covenants, these global commitments took on the force of international law, as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Measured and Measurable:

- UNESCO has been formally vested with the mandate for monitoring international commitments in this field. Many countries have adopted the UNESCO Media Development Indicators as a tool for measuring progress towards effective media systems at the country level.

- ITU provides data on Internet use and access.

- IPU tracks legislative and constitutional guarantees of public access to public information.

- UNHCHR reports on violations of media freedom.

The assembled coalition proposes that UNESCO, as the UN agency mandated to promote free, independent, and pluralistic media, take the lead role in monitoring progress toward the achievement of these goals. The UNESCO Institute of Statistics should play an advisory role in the collection of relevant data. A UN process should help build national capacities to gather data and promote dialogue on freedom of expression and public access to information.

Indicators_Post2015.pdf

27 Mar 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features

Frank La Rue, UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, was interviewed by Index on Censorship’s CEO Kirsty Hughes, on his experience surrounding digital freedom while in office. Watch the Google Hangout below.