Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

On the third anniversary of the start of the mass trial of 94 individuals, including government critics and advocates of reform, 10 human rights organisations appeal to the government of the United Arab Emirates to release immediately and unconditionally all those imprisoned solely for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression, association, and assembly as a result of this unfair trial.

The human rights organisations deplore the UAE government’s disregard for its international human rights obligations and its failure to act on recommendations from United Nations human rights experts that it release activists sentenced at the unfair trial.

Dozens of the activists, including prominent human rights defenders, judges, academics, and student leaders, had peacefully called for greater rights and freedoms, including the right to vote in parliamentary elections, before their arrests. They include prominent human rights lawyers Dr. Mohammed Al-Roken and Dr. Mohammed Al-Mansoori, Judge Mohammed Saeed Al-Abdouli, student leader Abdulla Al-Hajri, student and blogger Khalifa Al-Nuaimi, blogger and former teacher Saleh Mohammed Al-Dhufairi, and senior member of the Ras Al-Khaimah ruling family Dr. Sultan Kayed Mohammed Al-Qassimi.

The organisations urge the UAE government to end its continuing use of harassment, arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, torture and other ill-treatment, and unfair trials against activists, human rights defenders and those critical of the authorities, and its use of national security as a pretext to crackdown on peaceful activism and to stifle calls for reform.

The 10 human rights organisations urge the UAE government, which is serving its second term as a member of the UN Human Rights Council, to demonstrate clearly that it engages with UN human rights bodies by implementing recommendations by UN human rights experts to protect the right to freedom of opinion and expression, and to freedom of association and peaceful assembly.

Speaking to the UN’S Human Rights Council (HRC) on 1 March 2016, the UAE’s Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Dr Anwar Gargash asserted that “we are determined to continue our efforts to strengthen the protection of human rights at home and to work constructively within the [Human Rights] council to address human rights issues around the world.”

As a member of the UN Human Rights Council, the UAE government must observe its pledge to the Council to uphold international human rights standards and must spare absolutely no effort in implementing human rights recommendations effectively; to do otherwise puts into question the UAE government’s commitment towards the promotion and protection of human rights at home.

The 10 human rights organisations further call on the UAE to mount an independent investigation into credible allegations of torture at the hands of the country’s State Security apparatus, including by immediately accepting the request by Juan Méndez, the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, to visit the UAE in the first half of 2016.

In her May 2015 report to the UN Human Rights Council, Gabriela Knaul, the UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, recommended that an independent body composed of professionals with international expertise and experience, including in medical forensics, psychology and post-traumatic disorders, should be established to investigate all claims of torture and ill-treatment alleged to have taken place during arrest and/or detention; such a body should have access to all places of detention and be able to interview detainees in private, and its composition should be agreed upon with defendants’ lawyers and families.

On 4 March 2013, the government commenced the mass, unfair trial of 94 defendants before the State Security Chamber of the Federal Supreme Court in Abu Dhabi. Those on trial included eight who were charged and tried in absentia. The government accused them, drawing on vaguely worded articles of the Penal Code, of “establishing an organisation that aimed to overthrow the government,” a charge which they all denied. On 2 July 2013, the court convicted 69 of the defendants, including the eight tried in absentia, sentencing them to prison terms of between seven and 15 years. It acquitted 25 defendants, including 13 women.

On 18 December 2015, the government of Indonesia forcibly returned to the UAE Abdulrahman Bin Sobeih, one of the defendants tried in absentia. He had intended to seek asylum but is now a victim of enforced disappearance in the UAE and at risk of torture and other ill-treatment.

The UAE 94 trial failed to meet international fair trial standards and was widely condemned by human rights organisations and UN human rights bodies. The court accepted as evidence “confessions” made by defendants, even though the defendants repudiated them in court and alleged that State Security interrogators had extracted them through torture or other duress when defendants were in pre-trial incommunicado detention, without any access to the outside world, including to lawyers. The court failed to order an independent and impartial investigation of defendants’ claims that they had been tortured or otherwise ill-treated in secret detention. The defendants were also denied a right of appeal to a higher tribunal, in contravention of international human rights law. Although the State Security Chamber of the Federal Supreme Court serves as a court of first instance, its judgements are final and not subject to appeal.

During the trial, the authorities prevented independent reporting of the proceedings, barring international media and independent trial observers from attending. The authorities also barred some of the defendants’ relatives from the courtroom; others were harassed, detained or imprisoned after they criticised on Twitter the proceedings and publicised torture allegations made by the defendants.

Blogger and Twitter activist Obaid Yousef Al-Zaabi, brother of Dr. Ahmed Al-Zaabi, who is one of the UAE 94 prisoners, has been detained since his arrest in December 2013. He was prosecuted by the State Security Chamber of the Federal Supreme Court on several charges based on his Twitter posts about the UAE 94 trial, including spreading “slander concerning the rulers of the UAE using phrases that lower their status, and accusing them of oppression” and “disseminating ideas and news meant to mock and damage the reputation of a governmental institution.” Despite his acquittal in June 2014, the authorities continue to arbitrarily detain him, even though there is no legal basis for depriving him of his liberty.

On-line activist Osama Al-Najjar was arrested on 17 March 2014 and prosecuted on charges stemming from messages he posted on Twitter defending his father, Hussain Ali Al-Najjar Al-Hammadi, who is also one of the UAE 94 prisoners. In November 2014, he was sentenced by the State Security Chamber of the Federal Supreme Court to three years’ imprisonment on charges including “offending the State” and allegedly “instigating hatred against the State.” He was also convicted of “contacting foreign organisations and presenting inaccurate information,” a charge which followed his meeting with the UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers during her official visit to the UAE in February 2014. Like all defendants convicted by this court, he was denied the right to appeal the verdict.

In his March 2015 report, Michel Forst, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, expressed serious concern about the arbitrary arrest and detention of Osama Al-Najjar. He expressed concern that his arrest and detention may have been related to his legitimate activities in advocating for justice and human rights in the UAE and the peaceful exercise of his right to freedom of opinion and expression, as well as his cooperation with the UN and its human rights mechanisms. The Special Rapporteur called on the government to ensure that human rights defenders can carry out their legitimate activities in a safe and an enabling environment, including through open and unhindered access to international human rights bodies such as the UN, its mechanisms and representatives in the field of human rights, without fear of harassment, stigmatisation or criminalisation of any kind.

The 10 human rights organisations also express concern at the introduction of retrogressive legislation and amendment of already repressive laws, thereby further suppressing human rights. In July 2015, the authorities enacted a new law on combating discrimination and hatred with broadly-worded provisions, which further erode rights to freedom of expression and association. The law defines hate speech as “any speech or conduct which may incite sedition, prejudicial action or discrimination among individuals or groups… through words, writings, drawings, signals, filming, singing, acting or gesturing” and provides punishments of a minimum of five years’ imprisonment, as well as heavy fines. It also empowers courts to disband associations deemed to “provoke” such speech, and imprison their founders for a minimum of 10 years, even if the association or its founder have not engaged in such speech. The highly repressive 2012 cybercrime law, used already to imprison dozens of activists and others expressing peaceful criticism of the government, was amended in February 2016 to provide even harsher punishments, including by raising fines from a minimum of 100,000 Dirhams ($27,226) to 2 million Dirhams ($544,521).

Increasingly, the UAE authorities are using these laws and others simply as a means to silence peaceful dissent and other expression on public issues, and to sentence human rights defenders or peaceful critics of the government to lengthy prison terms.

The 10 human rights organisations urgently call on the UAE government to:

Signed:

Amnesty International

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

ARTICLE 19

English PEN

Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR)

Index on Censorship

International Commission of Jurists

International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

Lawyers Rights Watch Canada (LRWC)

PEN International

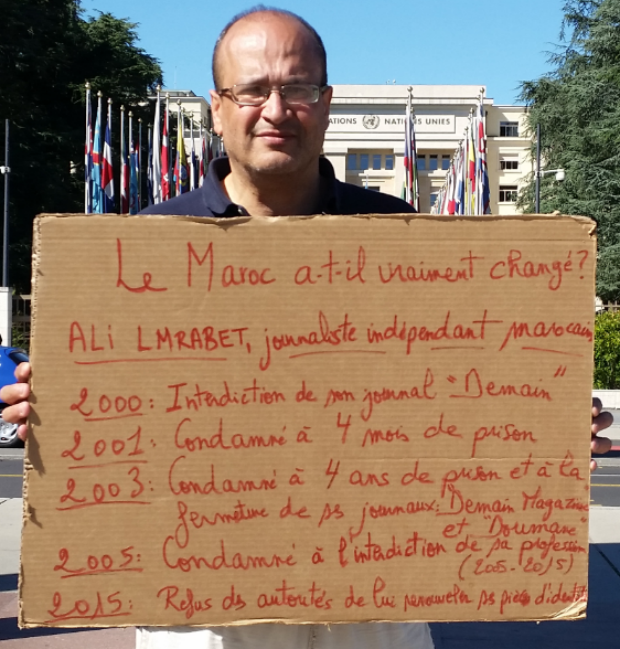

Ali Lmrabet is on hunger strike outside the UN building in Geneva (Photo: alisinpapeles.blogspot.com.es)

Outside the United Nations building in Geneva, Switzerland, Ali Lmrabet is in his 28th day of a hunger strike. The journalist and satirist is protesting what he sees as the latest bid from his country Morocco to stop him from doing his job.

In a period spanning over a decade, Lmrabet, who was the editor of two satirical publications, has continuously been targeted by Moroccan authorities. In 2003, he was jailed for reporting on personal and financial affairs of Morocco’s King Mohammed VI. His magazine Demain was banned. Though initially handed down a three-year sentence, Lmrabet was released after six months. But his troubles were far from from over: in 2005, he was banned from practising journalism in his home country for ten years, over comments made about the dispute in Western Sahara between Morocco and the Algerian-backed Polisario Front.

Now authorities are seemingly using bureaucracy as a tool to try and silence Lmrabet again. As his ban expired in April this year, he returned to Morocco with the aim of relaunching Demain. But there he was denied a residency permit, without which he is unable to set up the magazine. In a further complication, he also needs the residence permit to renew his passport. When this expired on 24 June, Lmrabet, who was in Geneva to participate in a session of the UN Human Rights Council, decided to start a hunger strike.

“He is very tired,” his partner Laura Feliu told Index on Censorship in a phone interview. She explained how the heat in Geneva has played a part in leaving Lmrabet drained of energy, and while he hasn’t had any serious health problems, he is experiencing sensations of seasickness.

Lmrabet’s protest takes place outside the UN offices, though a heatwave forced him to move inside on Sunday. He sleeps in a Protestant church near the centre of the city. Subsisting on water and some sugar and salt, he has lost at least seven kilograms since the start of the strike.

“He started a hunger strike to protest because he has been denied the right to work as a journalist,” Feliu explained. But in addition to having his free expression and press freedom curtailed, he also has another problem, she adds: “He is denied his right to an identity.”

Lmrabet has support in his country. Some 100 well-known Moroccans from the worlds of media, human rights and academia have signed a petition to the government calling on him to be allowed to renew his documents and continue his work in journalism. Independent and prominent human rights organisations in Morocco are also backing him, according to Feliu.

The response from Moroccan authorities, meanwhile, has so far been unsympathetic. The country’s UN ambassador Mohamed Aujjar has urged Lmrabet to contest what he labelled an “administrative decision” in Morocco, telling AFP that “you don’t get your papers by staging a hunger strike”. Lmrabet, on his part, is unwilling to risk being stranded in Morocco without papers and the ability to work or leave the country. “No one trusts the judical system in Morocco,” he said.

Feliu says it’s difficult to know what the outcome will be, but that Lmrabet is convinced this is the only way to protest. And he remains hopeful.

“He is very convinced of his fight. He is very convinced of his cause. He says that he has the moral to do it.”

Join us 30 July at Stand Up for Satire, a fundraiser in support of Index on Censorship.

This article was posted on 21 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

As so often at the sessions of the United Nations Human Rights Council, some interventions by states go unnoticed.

Under the famous ceiling of room XX created by Miquel Barcel in the Palais des Nations in Geneva, the on-going session of the Council is no different. Some of those unnoticed statements deserve our attention.

One in particular.

On Thursday, 5 March, one of the United Nations’ chief human rights voices, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, presented his first annual report to the council. It is his first since he took up the position of high commissioner for human rights in September 2014. From terrorism, torture and harassment of human rights defenders to the reorganisation of his office, the high commissioner’s report aims at presenting the state of human rights, the major threats against them and how he aims at building up his office to face those realities.

Al Hussein’s mandate, which Norway at the council called “an authoritative voice on human rights, built on […] repeated confirmation of its independence,” is what the Russian Federation in fact wants to silence.

Russia, which is today one of the 47 members of the council, was infuriated at the high commissioner’s statement presenting his report. It is traditional for states mentioned by international human rights mechanisms to accuse such instruments for being politicised and obeying “double standards.”

Russia went a step further by “condemning the high commissioner’s attempts to stigmatise any states for their acts or omissions in the field of human rights, even if they indeed took place.” Russia does not refer to politicisation or to attention the high commissioner would be giving to situations in certain countries only, but instead calls upon the United Nations voice for human rights to stop mentioning any country all together, whatever human rights violation took place in the country. In fact, Russia calls for the high commissioner to be silent.

Such a statement should not remain unnoticed because it sheds light on how Russia sees the international system; not one of standards and principles challenging states but rather one of obedience and muteness serving the states. The challenge Russia is facing with the high commissioner’s report is in fact a reflection of its disrespect for international law, be it in the way it has led suppression of civil society at home or its military activities in Ukraine, including the annexation of Crimea.

Because we must applaud those who stand firm for rights, we must also make sure that declarations by states who aim at silencing them do not go unnoticed. This one in particular.

This guest post was published on 10 March 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

An international coalition of more than 200 organisations welcomes the inclusion of targets for capable institutions, media freedom, and access to information by the United Nations member states now participating in the post-2015 development agenda dialogue.

The inclusion of targets on freedom of expression and access to information will help build stronger media and civil society institutions to closely and independently monitor all post-2015 development commitments.

The Open Working Group proposed on June 2, 2014, that the Sustainable Development Goal No. 16 to “achieve peaceful and inclusive societies, rule of law, effective and capable institutions” include sub-goals to “improve public access to information and government data” and “promote freedom of media, association and speech.”

UNESCO and the Global Forum for Media Development convened representatives of this coalition to consider how to strengthen these welcome initiatives and submit for the consideration of member states proposed language and indicators for the text now being discussed by the Open Working Group.

Our proposal is consistent with the criteria that are guiding the efforts to reach consensus on the post-2015 global development agenda, including the Sustainable Development Goals. We urge the continued inclusion of sub-goals 16.14 and 16.17, and we propose below several specific, measurable indicators to achieve these objectives by 2030.

UN Precedents:

Measured and Measurable:

The assembled coalition proposes that UNESCO, as the UN agency mandated to promote free, independent, and pluralistic media, take the lead role in monitoring progress toward the achievement of these goals. The UNESCO Institute of Statistics should play an advisory role in the collection of relevant data. A UN process should help build national capacities to gather data and promote dialogue on freedom of expression and public access to information.