12 Sep 2019 | Magazine, News, Volume 48.03 Autumn 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley argues in the autumn 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine that travel restrictions and snooping into your social media at the frontier are new ways of suppressing ideas” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

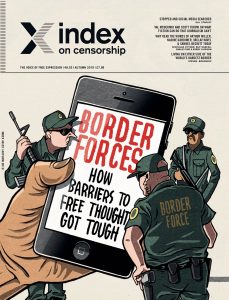

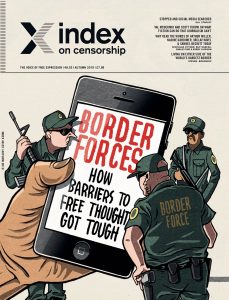

Border Forces – how barriers to free thought got tough

Travelling to the USA this summer, journalist James Dyer, who writes for Empire magazine, says he was not allowed in until he had been questioned by an immigration official about whether he wrote for those “fake news” outlets.

Also this year, David Mack, deputy director of breaking news at Buzzfeed News, was challenged about the way his organisation covered a story at the US border by an official.

He later received an official apology from the Customs and Border Protection service for being questioned on this subject, which is not on the official list of queries that officers are expected to use.

As we go to press, the UK Foreign Office updated its advice for travellers going between Hong Kong and China warning that their electronic devices could be searched.

This happened a day after a Sky journalist had his belongings, including photos, searched at Beijing airport. US citizen Hugo Castro told Index how he was held for five hours at the USA-Mexico border while his mobile phone, photos and social media were searched.

This kind of behaviour is becoming more widespread globally as nations look to surveil what thoughts we have and what we might be writing or saying before allowing us to pass.

This ends with many people being so worried about the consequences of putting pen to paper that they don’t. They fret so much about being prevented from travelling to see a loved one or a friend, or going on a work trip, that they stop themselves from writing or expressing dissent.

If the world spins further in this direction we will end up with a global climate of fear where we second-guess our desire to write, tweet, speak or protest, by worrying ourselves down a timeline of what might happen next.

So what is the situation today? Border officials in some countries already seek to find out about your sexual orientation via an excursion into your social media presence as part of their decision on whether to allow you in.

Travel advisors who offer LGBT travel advice suggest not giving up your passcodes or passwords to social media accounts. One says that, before travelling, people can look at hiding their social media posts from people they might stay within the destination country. Digital security expert Ela Stapley suggests going further and having an entirely separate “clean” phone for travelling.

These actions at borders have not gone unnoticed by technology providers. The big dating apps are aware that information to be found in their spaces might also prove of interest to immigration officials in some countries.

This summer, Tinder rolled out a feature called Traveller Alert – as Mark Frary reports on – which hides people’s profiles if they are travelling to countries where homosexuality is illegal. Borders are getting bigger, harder and tougher.

It is not just about people travelling, it’s also about knowledge and ideas being stopped. As security services and governments get more tech-savvy, they see more and more ways to keep track of the words that we share. Surely there’s no one left out there who doesn’t realise the messages in their Gmail account are constantly being scanned and collected by Google as the quid pro quo for giving you a free account?

Google is collecting as much information as it can to help it compile a personal profile of everyone who uses it. There’s no doubt that if companies are doing this, governments are thinking about how they can do it too – if they are not already.

And the more they know, the more they can work out what they want to stop.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Border officials in some countries already seek to find out about your sexual orientation via an excursion into your social media presence as part of their decision on whether to allow you in” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

In democracies such as the UK, police are already experimenting with facial recognition software. Recently, anti-surveillance organisation Big Brother Watch discovered that private shopping centres had quietly started to use facial recognition software without the public being aware.

It feels as though everywhere we look, everyone is capturing more and more information about who we are, and we need to worry about how this is being used.

One way that this information can be used is by border officials, who would like to know everything about you as they consider your arrival. What we’ve learned in putting this special issue together is that we need to be smart, too. Keep an eye on the laws of the country you are travelling to, in case legislation relating to media, communication or even visas change.

Also, have a plan about what you might do if you are stopped at a border. One of the big themes of this magazine over the years is that what happens in one country doesn’t stay in one country. What has become increasingly obvious is that nation copies nations, and leader after leader spots what is going on across the way and thinks: “I could use that too.”

We saw troll factories start in Mexico with attempts to discredit journalists’ reputations five years ago, and now they are widespread. The idea of a national leader speaking directly to the public rather than giving a press conference, and skipping the “need” to answer questions, was popular in Latin America with President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, of Argentina, and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez.

A few years later, national leaders around the world have grabbed the idea and run with it. It’s so we don’t have to filter it through the media, say the politicians. While there’s nothing wrong, of course, with having town hall chats with the public, one has a sneaking suspicion that another motivation might be dodging any difficult questions, especially if press conferences then get put on hold. Again, Latin America saw it first.

Given this trend, we can expect that when one nation starts asking for access to your social media accounts before they give you a visa, others are sure to follow. The border issue is broader than this, of course. Migration and immigration are issues all over the world right now, topping most political agendas, along with security and the economy. Therefore, governments are seeking to reduce immigration and restrict who can enter their countries – using a variety of methods.

In the USA and the UK, artists, academics, writers and musicians are finding visas harder to come by. As our US contributing editor, Jan Fox, reports, this has led to an opera singer removing posts from Facebook because she worries about her visa application, and academics self-censoring their ideas in case it limits them from studying or working in the USA. Where does this leave free expression? Less free than it should be, certainly. This is not the only attack on freedom of expression. Making it more difficult for outsiders to travel to these countries means stories about life in Yemen, Syria and Iran, for instance, may not be heard.

We don’t hear firsthand what it is like, and our knowledge shrinks. This policy surely reached a limit when Kareem Abeed, the Syrian producer of an Oscar-nominated documentary about Aleppo, was initially refused a visa to at-tend the Oscar ceremony. Meanwhile, UK festival directors are calling for their government to change its attitude and warn that artists are already excluding the UK from their tours.

One person who knew the value of getting information out beyond the borders of the country he lived in was a former editor of this magazine, Andrew Graham-Yooll, and we honour his work in this issue. His recent death gave us a chance to review his writing for us and for others. A consummate journalist, Graham-Yooll continued to write and report until just weeks before his death, and I know he would have had his typing fingers at the ready for a critique of what is happening in the Argentinian election right now.

Graham-Yooll took the job of editor of Index on Censorship in 1989, after being forced to leave his native Argentina because of his reporting. He had been smuggling out reports of the horrifying things that were happening under the dictatorship, where people who were activists, journalists and critics of the government were “disappearing” – a soft word that means they were being murdered. Some pregnant women were taken prisoner until they gave birth. Their babies were taken from them and given to military or government-friendly families to adopt, while the mothers were drugged and then dropped to their death, from airplanes, at sea.

Many of the appalling details of what happened under the authoritarian dictatorship only became clear after it fell, but Graham-Yooll took measures to smuggle out as many details as he could, to this publication and others, until he and his family were in such danger he was forced to leave Argentina and move to the UK.

Throughout history the powerful have always attempted to suppress information they didn’t want to see the light. We are in yet another era where this is on the rise.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on border forces

Index on Censorship’s autumn 2019 issue is entitled Border forces: how barriers to free thought got tough

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”How barriers to free thought got tough” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F09%2Fmagazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at borders round the world and how barriers to free thought got tough[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”108826″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/09/magazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Aug 2018 | Statements

Index on Censorship condemns the apparent decision by Google to do business in China.

According to a report published by the Intercept, leaked documents disclose the Google is planning a censored search engine in the country.

“We’re appalled that Google — which has repeatedly stressed its commitment to freedom of expression – should effectively collude with one of the world’s most oppressive regimes in this way. We will be urging Google to drop Dragonfly and resist attempts by governments worldwide to restrict freedom of speech rather than providing those governments with tools to further undermine democracy,” Jodie Ginsberg, Chief Executive, Index on Censorship said.

21 May 2018 | Digital Freedom, European Union, Germany, News, Russia, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”85524″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]For around six decades after WWII ideas, laws and institutions supporting free expression spread across borders globally. Ever more people were liberated from stifling censorship and repression. But in the past decade that development has reversed.

On April 12 Russian lawmakers in the State Duma completed the first reading of a new draft law on social media. Among other things the law requires social media platforms to remove illegal content within 24 hours or risk hefty fines. Sound familiar? If you think you’ve heard this story before it’s because the original draft was what Reporters Without Borders call a “copy-paste” version of the much criticized German Social Network law that went into effect earlier this year. But we can trace the origins back further.

In 2016 the EU-Commission and a number of big tech-firms including Facebook, Twitter and Google, agreed on a Code of Conduct under which these firms commit to removing illegal hate speech within 24 hours. In other words what happens in Brussels doesn’t stay in Brussels. It may spread to Berlin and end up in Moscow, transformed from a voluntary instrument aimed at defending Western democracies to a draconian law used to shore up a regime committed to disrupting Western democracies.

US President Donald Trump’s crusade against “fake news” may also have had serious consequences for press freedom. Because of the First Amendment’s robust protection of free expression Trump is largely powerless to weaponise his war against the “fake news media” and “enemies of the people” that most others refer to as “independent media”.

Yet many other citizens of the world cannot rely on the same degree of legal protection from thin-skinned political leaders eager to filter news and information. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has documented the highest ever number of journalists imprisoned for false news worldwide. And while 21 such cases may not sound catastrophic the message these arrests and convictions send is alarming. And soon more may follow. In April Malaysia criminalised the spread of “news, information, data and reports which is or are wholly or partly false”, with up to six years in prison. Already a Danish citizen has been convicted to one month’s imprisonment for a harmless YouTube video, and presidential candidate Mahathir Mohammed is also being investigated. Kenya is going down the same path with a draconian bill criminalising “false” or “fictitious” information. And while Robert Mueller is investigating whether Trump has been unduly influenced by Russian President Putin, it seems that Putin may well have been influenced by Trump. The above mentioned Russian draft social media law also includes an obligation to delete any “unverified publicly significant information presented as reliable information.” Taken into account the amount of pro-Kremlin propaganda espoused by Russian media such as RT and Sputnik, one can be certain that the definition of “unverified” will align closely with the interests of Putin and his cronies.

But even democracies have fallen for the temptation to define truth. France’s celebrated president Macron has promised to present a bill targeting false information by “to allow rapid blocking of the dissemination of fake news”. While the French initiative may be targeted at election periods it still does not accord well with a joint declaration issued by independent experts from international and regional organisations covering the UN, Europe, the Americans and Africa which stressed that “ general prohibitions on the dissemination of information based on vague and ambiguous ideas, including ‘false news’ or ‘non-objective information’, are incompatible with international standards for restrictions on freedom of expression”.

However, illiberal measures also travel from East to West. In 2012 Russia adopted a law requiring NGOs receiving funds from abroad and involved in “political activities” – a nebulous and all-encompassing term – to register as “foreign agents”. The law is a thinly veiled attempt to delegitimise civil society organisations that may shed critical light on the policies of Putin’s regime. It has affected everything from human rights groups, LGBT-activists and environmental organisations, who must choose between being branded as something akin to enemies of the state or abandon their work in Russia. As such it has strong appeal to other politicians who don’t appreciate a vibrant civil society with its inherent ecosystem of dissent and potential for social and political mobilisation.

One such politician is Victor Orban, prime minister of Hungary’s increasingly illiberal government. In 2017 Orban’s government did its own copy paste job adopting a law requiring NGOs receiving funds from abroad to register as “foreign supported”. A move which should be seen in the light of Orban’s obsession with eliminating the influence of anything or anyone remotely associated with the Hungarian-American philanthropist George Soros whose Open Society Foundation funds organisations promoting liberal and progressive values.

The cross-fertilisation of censorship between regime types and continents is part of the explanation why press freedom has been in retreat for more than a decade. In its recent 2018 World Press Freedom Index Reporters Without Borders identified “growing animosity towards journalists. Hostility towards the media, openly encouraged by political leaders, and the efforts of authoritarian regimes to export their vision of journalism pose a threat to democracies”. This is something borne out by the litany of of media freedom violations reported to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom, which monitors 43 countries. In just the last four years, MMF has logged over 4,200 incidents — a staggering array of curbs on the press that range from physical assault to online threats and murders that have engulfed journalists.

Alarmingly Europe – the heartland of global democracy – has seen the worst regional setbacks in RSF’s index. This development shows that sacrificing free speech to guard against creeping authoritarianism is more likely to embolden than to defeat the enemies of the open society.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”100463″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” link=”http://www.freespeechhistory.com”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

A podcast on the history of free speech.

Why have kings, emperors, and governments killed and imprisoned people to shut them up? And why have countless people risked death and imprisonment to express their beliefs? Jacob Mchangama guides you through the history of free speech from the trial of Socrates to the Great Firewall.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526895517975-5ae07ad7-7137-1″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Apr 2018 | Awards, China, Digital Freedom, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/aT1dO5oekso”][vc_column_text]

GreatFire are the 2016 Digital Activism Fellow

In a speech given this past February at an invitation-only Index event, Index 2016 Digital Awards Fellow GreatFire asked the audience whether “the global internet is bringing free speech, or is China bringing censorship to the global internet?”

Trying to do its part in bringing free speech to Chinese internet users, the anonymous nonprofit recently launched its Patreon crowdfunding campaign on March 30.

In the wake of the March National People’s Congress, which swept away presidential term limits, and Apple’s deal to have state-owned enterprise Guizhou-Cloud Big Data (GCBD) host its data, the fight against Chinese censorship is facing an uncertain future.

“Xi Jinping wants to make sure that all criticism, at home and abroad, can be silenced,” said Charlie Smith, GreatFire co-founder.

Apple is helping Xi Jinping and the Communist Party do just that, according to Smith. In the February speech, GreatFire said, “China’s Communist Party has surprised everyone by becoming experts at censorship technology.”

Smith wouldn’t be surprised if “Apple shared private user information about Apple customers outside of China with the Chinese authorities, in cases where those users may be ‘stirring up trouble’ against China.”

GreatFire’s February speech also cited that “when pressured by a letter from two US senators last year, Apple admitted to having censored more than 700 apps just in the VPN category.”

“Apple is working hand-in-hand with the Chinese authorities to implement censorship, not just in China, but around the world,” said Smith. “At the moment, this mainly affects Chinese [customers] but the writing is on the wall – all Apple customers will soon find that it will become increasingly more difficult and perhaps impossible to access negative information about the ruling Communist Party and party officials.”

However, Smith hopes other big-name companies like Google will re-enter China’s market without having to censor and not follow Apple’s footsteps. In 2010, Google shut down its operations after Chinese human-rights activists had their Gmails hacked, and the company has yet to come back.

“Google has the technical know-how, the expertise and the money to be able to offer an uncensored version of its search engine to an audience in China,” said Smith. “Google has the power to offer a 100% uncensored service to China’s 700 million plus internet users. If we can do it, they can do it.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”98218″ img_size=”medium” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/03/amazing-banned-memes-china/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”85698″ img_size=”medium” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/02/six-sites-blocked-by-chinas-great-firewall”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]The February speech also noted that following Google’s departure, “the vast majority of Chinese internet users exclusively use domestic services that are completely controlled by the Communist Party.”

If Google were to re-enter the market without censoring itself, it would destroy “a firewall that is preventing more than 700 million people from freely accessing information [and] would be the most important development in the history since the development of the internet itself,” said Smith.

Unlike his optimism for Google, Smith wishes China had lost Apple to Chinese censorship instead of it mixing its business with GCBD.

“Apple will likely not share transparency reports about requests that the Chinese authorities are making for private information,” said Smith. “People who get detained by the authorities for ‘stirring up trouble,’ which is a common, catch-all description for those who express their displeasure about anything related to the Communist Party, may not even know that they ended up in detention because Apple shared their private information with the authorities.”

With the stage set for the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, journalists, tourists and athletes will be hitting China’s Great Firewall “if companies and individuals do not stand up to [China’s] censorship,” said Smith, adding that “the situation will only get worse.”

Unable to fund its operations directly from Chinese users because of official intimidation, GreatFire’s Patreon launch looks to individuals for financial help, hopefully shifting itself away from reliance on funding organisations.

Because “most internet freedom funding is for shiny new things,” GreatFire is utilizing Patreon to fund its ongoing projects and not new ones, said Smith. Patreon, a member-subscription platform to generate funds for content creators, will allow GreatFire to maintain its existing sites and continue to combat China’s Great Firewall.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1522746056610-05bb1437-96d7-5″ taxonomies=”8199″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]