10 Jul 2017 | Asia and Pacific, Campaigns -- Featured, China, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Update: On 13 July 2017 the Chinese Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, jailed for his pro-democracy work, died in hospital aged 61.

Chinese Nobel Peace Prize laureate and writer Liu Xiaobo, who was imprisoned since 2009 for calling for more freedom in his country, has been diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. He was recently released into hospital for treatment and his state of health is considered critical.

Index calls on the UK government to urge China to release Liu immediately and allow him to travel abroad for treatment. It also calls on the UK ambassador to visit Liu and his wife the poet Liu Xia in the hospital. In the past few days, Liu has reiterated his request to be able to travel to have medical treatment.

Liu’s friends and journalists report trying to visit the couple in the hospital and being beaten by police.

In December 2008, Liu co-drafted Charter 08, a document modelled on Václav Havel’s Charter 77, written in Communist Czechoslovakia 30 years earlier. The document outlines the basic principles and fundamental rights that should govern China’s political landscape including freedom of association. Over 350 intellectuals and activists initially signed it, with a further 10,000 people including academics, journalists and businessmen adding their names to it upon its release. The government’s reaction to Charter 08 was swift and harsh. Liu was initially arrested two days prior to its official publication and later charged with 11 years in prison for incitement to subversion, during a trial in which he said he had no enemies. Index has repeatedly called for his release.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1499953076038-54c71786-d828-10″ taxonomies=”85″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Jul 2017 | Index in the Press

Human rights defender Nabeel Rajab has been sentenced to two years in prison in Bahrain for “broadcasting fake news”. A court ruled that he had undermined the “prestige” of the kingdom, the state news agency reports. Read the full article

10 Jul 2017 | Artistic Freedom, News and features, Volume 46.02 Summer 2017 Extras, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Members of Index’s youth board looked at three famous works that fell victim to the Russian censors”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the long-term consequences of 1917 Russian Revolution, which launched the global communist experiment, and the long-term impact that it had on free speech around the world. Here, three members of Index’s youth board give examples of works that failed to find favour with the authorities the revolution ushered in.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The original Italian edition of Dr Zhivago. Credit: Wikimedia

Dr Zhivago – Boris Pasternak

Isabela Vrba Neves (Stockholm)

A depiction of Russian life between the Bolshevik Revolution and World War II, Dr Zhivago (1957) by Boris Pasternak is a piece of literature presenting the reader with romance and the tragedies experienced by Russians during the early twentieth century.

Dr Zhivago tells the story of Yuri Zhivago, a man suffering hardship throughout his life, from becoming an orphan to being in love with two women and arousing the suspicions of those in power. Through an intricate plot introducing many characters, Zhivago witnesses the revolution and civil war, all while exploring questions of religion and philosophy.

Pasternak submitted his book for publishing in 1956 but was rejected in the Soviet Union due to it containing anti-Soviet passages and criticism of the Bolsheviks. As a result, the book was banned in the Soviet Union until 1988. However, in 1957 a manuscript was smuggled to Milan, where it was first published.

The following year Pasternak was awarded a Nobel Prize in Literature, which he had to turn down after being threatened with ejection from the Soviet Union. The award was later accepted in 1988 by his relatives.

A film adaptation of Dr Zhivago was released in 1965, starring the late actor Omar Sharif and Geraldine Chaplin. Immensely popular in Europe and North America, the film adaption was also banned for many years in the Soviet Union.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The cover of Stefan Zweig’s Beware of Pity. Credit: Wikimedia

The Collected Novellas of Stefan Zweig

Samuel Rowe (London)

As I was leaving a house on the outskirts of Copenhagen some summers ago, I was handed a bright orange hardback book. It was The Collected Novellas of Stefan Zweig. I was told that Zweig’s novel, Beware of Pity, had loosely inspired the 2014 Wes Anderson film The Grand Budapest Hotel and that Zweig’s works had been burned in the streets during the Third Reich. But this was not the first time his literature had been burned.

Not long before – 30 October 1929, to be precise – Krupskaia Lenin, wife of Vladmir, had sent out a circular to all librarians in the Soviet Union. It contained a list of literature considered decadent or which fostered “social pessimism”, and required they be removed from all public libraries. Zweig’s stories could have fallen into the former or the latter category; his stories were popular and hilarious, subversive and frank.

Once the procedure was completed, two copies of each title on the list were sent to the central library of each region, accessible only to qualified researchers.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

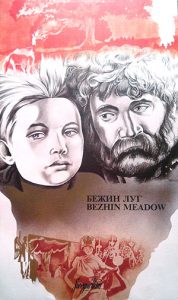

A poster for Bezhin Meadow. Credit: Wikimedia

Bezhin Meadow – Sergei Eisenstein

Sophia Smith-Galer (London)

One of the most famous films to have been scuppered by censorship in the Soviet Union was Bezhin Meadow, a film adaptation of the story Bezhin lug by Ivan Turgenev. The film, directed by Sergei Eisenstein, was believed to have been destroyed before its completion, but parts of it resurfaced in the 1960’s, allowing for a crude recreation.

The main character Ivan’s life story was based on the life of Pavlik Morozov, a young Russian boy who denounced his father to the Soviet Union and, ultimately, died at the hands of his family. It grew to become a story of political martyrdom after his death in 1932.

Sergei Eisenstein was nonetheless already a world famous film director – Battleship Potemkin (1925) is still used as an example of groundbreaking cinematography to this day – and is best remembered for pioneering the montage.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This piece was written by members of Index on Censorship’s youth advisory board. You can find out more about the youth advisory board here

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”100 Years On” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F06%2F100-years-on%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the consequences of the 1917 Russian Revolution still affect freedoms today, in Russia and around the world.

With: Andrei Arkhangelsky, BG Muhn, Nina Khrushcheva[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/magazine”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Jul 2017 | Asia and Pacific, China, Digital Freedom, News and features

Update: On 13 July 2017 the Chinese Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, jailed for his pro-democracy work, died in hospital aged 61.

When Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, Chinese authorities were sent into a state of panic. Liu had been in prison since 2009, following the release of Charter 08, a pamphlet he co-wrote that called for greater democratic freedoms. As the world’s attention was on China and on Liu, all references to Liu and the prize were blocked online and off. Then his wife and many of his acquaintances were detained in an attempt to stop them from going to Oslo and collecting it on his behalf. At the ceremony itself, an empty chair became a stark reminder of his absence and soon the words “empty chair” started to race through the internet. These too were blocked.

Liu has since remained in prison and efforts to stamp out his name continue. But last week he once again made headlines following his release from prison on health grounds. At the time of writing, reports say Liu, who is suffering from late-stage liver cancer, is close to death. For free speech advocates around the world, this news is saddening. No figure has come to represent the fight for Chinese democracy as much as Liu Xiaobo.

Born in 1955 in Jilin province in northeast China, the son of two teachers, Liu went on to become a writer, activist and academic. It was while teaching at Columbia’s Barnard College in New York in 1989 that the Tiananmen Square protests broke out. Liu decided to return to China to take part in them on their final, fateful day. This led to his arrest and imprisonment, the first of four times.

Liu was shunned by China’s academic community when he left prison two years later, but that did not silence him and he continued to build on his reputation within China as an outspoken critic of the Communist Party. He also started a tradition of writing poems about Tiananmen every year to mark the anniversary – a powerful reminder that the government does not have a monopoly on memory.

For Liu the internet was a lifeline. He described it as “God’s gift to the Chinese people” in an essay that was published in Index on Censorship magazine in 2006. The web became his primary portal to publish his thoughts to the outside world and to reach audiences when traditional forms of media were out of bounds. Liu wrote that “the effect of the internet in improving the state of free expression in China cannot be underestimated”.

Liu’s influence peaked in December 2008 with Charter 08, a document modelled on Václav Havel’s Charter 77, written in Communist Czechoslovakia 30 years earlier. The document outlines the basic principles and fundamental rights that should govern China’s political landscape. Over 350 intellectuals and activists initially signed it, with a further 10,000 people including academics, journalists and businessmen adding their names to it upon its released. The government’s reaction to Charter 08 was swift and harsh. Liu was initially arrested two days prior to its official publication and later charged with 11 years in prison for incitement to subversion, during a trial in which he said he had no enemies. Index has repeatedly called for his release.

Isabel Hilton, a leading expert on China, told Index back in 2010 that “when the history of free expression and freedom of ideas is written, he and the other signatories of Charter 08 will be remembered as courageous citizens who sought the best for their country”.

In an interview Liu gave prior to his arrest, he said: “The way I see it, people like me live in two prisons in China. You come out of the small, fenced-in prison, only to enter the bigger, fenceless prison of society.” Since Liu’s arrest almost a decade ago, China has continued to change at breakneck speed. When it comes to human rights and free speech, sadly this change has been predominantly for the worse. The bigger, fenceless prison that Liu spoke of is today a lot more closed and draconian. China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, has overseen a huge crackdown on dissent. And the internet, God’s gift to China, is more regulated that ever before. Even seemingly innocent entertainment channels are frequently shut down, such as Kuaishou, a video-sharing site, which Index on Censorship reported on in its most recent issue.

Despite this, people continue to fight for greater freedom and rights in China, exploiting loopholes online as and when they can, and showing remarkable courage in the face of extreme adversity. The role of Liu in setting an example and providing inspiration cannot be underplayed. Liu’s Nobel chair might still be empty, but he is never forgotten, nor will he ever be.

Read more:

Liu Xiaobo’s article on the power of the internet in full

A poem by Liu translated for Index on Censorship magazine

Esteemed writer Ma Jian’s response to the Nobel Peace Prize and thoughts on Liu

The government ban of words related to Liu Xiaobo and the Nobel Peace Prize