10 Jun 2021 | News and features, United States, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021 extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116867″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Shalom Auslander likes to shock. His latest novel, Mother for Dinner, is about a family of cannibals. It’s funny, outrageous and a bitter critique on US society and identity politics.

Auslander was born into an ultra-orthodox Jewish family in Monsey, New York, which he has also written about in his memoir, Foreskin’s Lament.

It is this upbringing which has inspired much of his work – the rituals and religion he rebelled against but is still attracted to, and in which he finds comfort.

Auslander has written an original short story for Index, published here, based on a ritual joke which he subverts, to challenge our sense of humour and readiness to be offended.

Anti-Ha by Shalom Auslander

A man walks into a pub and sits down at the bar. At the table nearby sit a rabbi, a priest and a nun with a parrot on her shoulder.

The bartender eyes them.

He doesn’t want any trouble.

The man’s name is Lipschitz, and he doesn’t want any trouble either. It’s been a long day, looking for a job, any job, but to no avail. Once upon a time he could earn a hundred dollars a night, at pubs much like this one, delivering his comedy routine to a joyful, appreciative crowd. But that feels like a long time ago. Now he just wants a drink. He would sit somewhere else if he could, well away from the possibility of a joke, but it is Friday night and the pub is full. For a moment he considers leaving. The bartender comes over.

“What can I get you?” the bartender asks.

Lipschitz glances at the table nearby.

The rabbi sips his scotch. The priest checks his phone. The nun orders a cranberry and soda.

“Just a beer,” says Lipschitz.

The parrot says nothing.

Nobody laughs.

Phew.

* * *

A beautiful blonde woman walks into a pub and sits down at the bar.

The woman’s name is Laila. She is of Islamic descent on her father’s side, and she sits at the bar beside Lipschitz, who is of Jewish descent on his mother’ side.

There’s nothing funny about that. The Arab-Israeli conflict has led to the loss of countless innocent lives.

The bartender comes over.

“What can I get you?” he asks.

Laila orders a martini.

She glances over at the rabbi, the priest and the nun with the parrot on her shoulder. Laila has a devilish glint in her eye, a certain mischievous sparkle that Lipschitz finds both alluring and troublesome.

“Well,” she says with a smile, “it’s better than a parrot with a nun on its shoulder.”

Uh-oh, thinks Lipschitz.

He doesn’t want any trouble.

The bartender, a young man with a ponytail and a scruffy goatee, casts a watchful eye over them. He wears a brown T-shirt with the words HUMOR LESS in large white letters across the front. Lipschitz had seen such shirts before – and the hats and the hoodies and the laptop stickers. The first time he saw it was a year ago, at what was to be his very last nightclub performance. He had made a joke about his mother, and a man in the front row, wearing the same shirt, stood up and began to heckle him.

“Boo!” the man shouted. “Mother jokes are weapons of the patriarchy designed to minimise the role of women in the parenting unit!”

Jokes and jest were the latest targets in the global battle against offence, affrontery and injustice. The movement’s founders, who proudly called themselves Anti-Ha, opposed humour in all its forms. They did so because they believed, as so many philosophers have, that jokes are based on superiority. Plato wrote that laughter was “malicious”, a rejoicing at the misery of others. Aristotle, in his Poetics, held that wit was a form of “insolence”. Hobbes decreed that laughter is “nothing else but sudden glory arising from a sudden conception of eminency in ourselves”, while Descartes went so far as to say that laughter was a form of “mild hatred”.

The heckler stormed out of the club, and half the audience followed him.

“Laughter,” read the back of his T-shirt, “Is The Sound of Oppression.”

The movement grew rapidly. In New York, you could be fined just for telling a riddle. A woman in Chicago, visiting a friend, stood at the front door and called, “Knock knock!” and wound up spending the night in jail.

In Los Angeles, long the vanguard of social progress, a man on Sunset Boulevard was recorded by a concerned passer-by laughing to himself as he walked down the street. The outraged passer-by posted the video online, where it instantly went viral and the man could no longer show his face outside. The subsequent revelation that the man suffered from Tourette’s Syndrome, and that his laughter was caused not by derision or superiority but by a defect in the neurotransmitters in his brain, did little to change anyone’s mind. No apologies were given nor regrets expressed; in fact, the opposition to humour only increased now that it was scientifically proven that laughter is caused by a brain defect, and “#Science” trended in the Number One spot for over two weeks.

Laila nudges Lipschitz.

“Hey,” she whispers. “Wanna hear a joke?”

Lipschitz stiffens.

“It’s a good one,” she sings.

Lipschitz knows she’s trying to tempt him. He knows he should head straight for the door. But it’s been a rough day, another rough day, and the booze isn’t working anymore, and soon he’ll have to go home and tell his mother and sister that he didn’t find work – again – and so in his languor and gloom, he looks into Laila’s dancing green-flecked eyes and says, with a shrug, “Sure.”

Laila leans over, hides her mouth with her hand and whispers the joke in his ear.

The rabbi and the priest discuss God.

The nun feeds her parrot some crackers.

Laila finishes the joke and sits back up, utterly straight-faced, as if nothing at all had happened. Lipschitz, though, cannot control himself. The joke is funny, and he can feel himself beginning to laugh. It begins as a slight tickle in his throat, then the tickle grows, swells, like a bright red balloon in his chest that threatens to burst at any moment.

Lipschitz runs for the door, trying to contain his laughter until he gets outside, but he bumps into a waitress as he goes, upsetting the serving tray in her hand and causing two orders of nachos and a side of fries to tumble to the ground.

Everyone stops to see what happened, except for Lipschitz, who is scrambling out the door.

The parrot says, “Asshole.”

Nobody laughs.

The parrot is being judgmental, and is only considering the man’s actions from its own privileged heteronormative perspective.

* * *

Lipschitz returns the following night, and the night after that. Hour after hour he sits beside his beloved Laila, and she whispers funny things in his ear – stories, jokes, observations, none of which can be repeated here for obvious legal reasons.

He becomes quite good at holding in his laughter, and leaving calmly as if nothing afoul is afoot, but sometimes, on the way home, he recalls one of Laila’s jokes, and he hears her voice in his head and he feels her breath on his ear, and he has to duck into an alley and bury his face in his coat in order to smother his riotous laughter.

Then, one night, as he returns home, his sister Sophie stops him. She examines his eyes, his face, his countenance.

“What have you been up to?” she demands. “Where have you been?”

Lipschitz feels terror grow in his chest. Sophie is a fiercely devoted activist, with nothing but contempt for the brother who once made his living encouraging people to laugh at breasts and vaginas and penises and gender differences and the elderly with impaired cognitive functional abilities. She would love to make an example of him and he knows it.

“Nowhere,” Lipschitz says.

“Then why is your face red?” she asks.

“It’s cold out.”

“It’s seventy degrees. Were you laughing?”

“I was just running,” he says, heading to his room. “It’s late.”

Lipschitz knows he is playing with fire, but he can’t stop himself. His father, abusive and violent, died when he was eleven. His mother became bitter and controlling, his sister foul and resentful. Life went from dark to darker, and humour was the only coping mechanism young Lipschitz had, a thin but luminous ray of light through the otherwise suffocating blackness of his life. He imagined God on Day One, looking down at the world He had created, with all its suffering and heartbreak and death and pain and sorrow, and realising that mankind was never going to survive existence without something to ease the pain.

“Behold,” declared God, “I shall give unto them laughter, and jokes, and punchlines and comedy clubs. Or the poor bastards won’t survive the first month.”

And so Lipschitz, despite the danger, returns to the pub again the following night, and he sits at the bar, beside a Russian, a Frenchmen, two lesbians and a paedophile, and he waits for Laila to show up.

That’s not funny, either. Singling out different nationalities only leads to contempt, and homosexuality has no relation to paedophilia.

After some time, the bartender approaches.

“She’s not coming,” he says.

“Why not?” asks Lipschitz.

“Someone reported her.”

Anger burns in Lipschitz.

It was Sophie, he knows it.

Lipschitz turns to leave, whereupon he finds two police officers waiting for him at the door. He is wanted for questioning. He must come down to the station.

“But I’m not going to drive drunk until later,” Lipschitz says.

Nobody laughs. Drunk-driving is a terrible crime that costs the lives of thousands of innocent people every year.

* * *

A witness in a Malicious Comedy case – two counts of Insolence, one count of Mild Hatred – is called to the stand.

The witness’s name is Lipschitz.

The defendant’s name is Laila.

Lipschitz takes the stand, and for the first time in weeks, his eyes meet hers. She smiles, and so great is the pain in his heart that he has to look away. Behind her, in the gallery, sit Lipschitz’s mother and sister, the bartender, the Russian, the Frenchmen, the two lesbians, the paedophile, the priest, the two cops, the rabbi and the nun with a parrot on her shoulder.

They scowl at him.

The prosecuting attorney approaches.

“Did you or did you not,” he asks Lipschitz, “on Thursday the last, discuss with the defendant the fate of two Jews who were stranded on a desert island?”

The audience gasps.

Lipschitz avoids making eye contact with Laila. If he does, he will laugh, and if he laughs, she will be found guilty. He fights back a smile.

“I did not,” says Lipschitz.

The prosecuting attorney steps closer.

“And did she not,” the prosecuting attorney demands, “on the Friday following, tell you what became of a Catholic, a Protestant and a Buddhist on the USS Titanic?”

Lipschitz wills himself to maintain his composure.

Out of the corner of his eyes, he sees Laila covering her own mouth, hiding her own smile, and he quickly looks away.

“She did not,” says Lipschitz.

The prosecuting attorney slams his fist on the witness stand.

“And did she not,” he shouts, “tell you of the elderly couple, one of whom has dementia and one of whom is incontinent? Was there no mention of them?”

Lipschitz cannot answer. If he tries to speak at all, he will laugh. He waits, shakes his head, tries to settle himself. He thinks of horrors, of tragedies, of injustice.

And then it happens.

Laila laughs.

She explodes with laughter, throwing her head back, her hand on her chest as if she might burst from joy.

“Order!” demands the judge.

Lipschitz begins to laugh, too. He laughs and laughs, and tears fill his eyes, and the judge bangs his gavel. He gets to his feet, furious at the outburst, but as he does, he steps on a banana peel and flips, head over heels, to the floor. The prosecuting attorney and bailiff rush to his aide, whereupon all three clunk heads and fall to the ground. Laila and Lipschitz laugh even harder, but the crowd does not. There’s nothing funny about head and neck injuries, which can cause cortical contusion and traumatic intracerebral hemorrhages.

“Guilty!” the judge yells as he holds his throbbing head. “Guilty!”

He clears the court, and orders Laila and Lipschitz taken away.

But later, when the bartender, the Russian, the Frenchmen, the two lesbians, the paedophile, the priest, the two cops, the rabbi and the nun meet at the pub, one and all swear they could still hear their laughter long after the courtroom was empty.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Jun 2021 | Kazakhstan, News and features, Slapps, Statements, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116855″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text](7 June 2021, London) – A legal case currently before the UK courts highlights the egregious tactics being used by Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation Limited (ENRC), a privately-owned Kazakh multinational mining company, in what appear to be deliberate attempts to escape public scrutiny.

The civil case brought by ENRC is against the UK’s anti-corruption authority, the Serious Fraud Office (SFO), and ENRC’s former lawyers, Dechert LLP. The SFO launched a formal corruption investigation into ENRC in April 2013, but has yet to bring any charges. The investigation has become one of the SFO’s longest running and most complicated cases. ENRC denies all allegations.

ENRC is suing the SFO for misfeasance in public office claiming the SFO mishandled the corruption investigation, induced Dechert lawyers to breach duties owed to ENRC, and leaked information to the media. ENRC claims Dechert and its partner, Neil Gerrard, were negligent and acted in breach of contract and fiduciary duties, including by leaking confidential information to the press. The SFO, Gerrard and Dechert all deny the allegations.

This is by no means an isolated example of ENRC using the courts in a way that discourages scrutiny and shuts down accountability. Since the SFO announced its investigation, ENRC has initiated a wave of more than 16 legal proceedings in the US and the UK against journalists, lawyers, investigators, contractors, a former SFO official and the SFO itself. The SFO has had to divert significant staff time and funding away from its corruption investigation to respond to the claims brought by ENRC.

The 22 undersigned human rights, freedom of expression and anti-corruption organisations are concerned that ENRC’s tactics are either a deliberate attempt to undermine the SFO’s corruption investigation and to silence those seeking to expose the company’s misdeeds or will serve to do so.

The groups believe that ENRC’s legal tactics include Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation or SLAPPs, a form of legal harassment used by powerful individuals and companies as a means of silencing public watchdogs, including journalists, peaceful protesters and whistleblowers. SLAPPs typically involve long and costly legal procedures, or the threat thereof, to intimidate and harass critics into silence.

The conduct of corruption investigations by state officials and others must, of course, be lawful and follow appropriate procedures, the undersigned organisations said, but they nonetheless raised concerns about what appeared to be vexatious litigation by ENRC.

“ENRC’s campaign of legal action across two jurisdictions targeting more than a dozen people and other entities seems a deliberate attempt to shift the focus away from ENRC’s alleged corruption to those conducting legitimate investigations, whether journalists or public authorities. If such efforts succeed, not only could it derail proper public scrutiny of the original allegations, but it risks setting a damaging example for how others can thwart corruption investigations and shut down public discourse,” the organisations said.

A recent legal suit by ENRC was initiated in September 2020 in US courts against publisher HarperCollins seeking disclosure of wide-ranging information relating to the publication of a book, Kleptopia, and newspaper articles published in the Financial Times by investigative journalist Tom Burgis. The book and articles investigate possible corruption and other alleged offences by ENRC and its owners, notably Alexander Machkevitch, one of the three oligarchs (known as the Trio), who – alongside the Kazakh state – own the controlling stake in ENRC.

Shortly after initiating the US action, ENRC’s lawyers also initiated legal action in the UK, sending a Letter Before Claim notifying HarperCollins UK, the Financial Times and Burgis of intended court proceedings for defamation. The case has yet to be issued. In January 2021, ENRC followed with another legal claim, this time against the SFO and John Gibson, a former SFO case controller, who led the investigation into ENRC, accusing him of leaking to the press, including to Burgis.

In a submission to the court, counsel for HarperCollins in the US described ENRC’s tactics as a “relentless campaign to squelch any coverage of its corruption.” She added, “ENRC has undertaken a campaign to silence all who dare expose its misdeeds, through initiating or threatening legal action….It has pursued its critics (even law enforcement) with numerous lawsuits…. HarperCollinsUS is now the latest target.”

Court documents filed in the numerous legal proceedings reveal not only the aggressive legal tactics, but also allege unlawful surveillance and spying by agents linked to ENRC, including of Burgis and current or former SFO officials.

“The UK and US courts will need to decide the merits of these cases, but we are deeply troubled by the chilling effect this wave of legal action has on legitimate investigative and anti-corruption work by journalists, law enforcement officials, and others,” the civil society groups said. “We cannot permit powerful actors with deep pockets to silence their critics, thwart legitimate investigations and target those whose efforts are crucial to ending corruption.”

The groups called on the UK government to urgently consider measures, including legal measures, that could be put in place to protect public watchdogs and journalists from abusive legal actions that are intent on silencing them. The rule of law, protection of human rights, and democracy rely on their ability to hold power to account, said the organisations.

They further urged the SFO to swiftly move forward its investigation into ENRC. “If the SFO has evidence of corruption to charge ENRC then it should do so. Lengthy corruption investigations with no end in sight provide fertile ground for dirty tactics against journalists, whistle-blowers, and other critics to flourish,” the groups said.

Notes to editors:

ENRC was listed on the London Stock Exchange until 2013, when it became embroiled in controversy over governance issues and its purchase of disputed mining concessions in the Democratic Republic of Congo. It went private and today its ultimate parent company is Eurasian Resources Group S.à.r.l., registered in Luxembourg. The ‘Trio’ who own the majority shares in ENRC (now ERG) are Alexander Machkevitch, Patokh Chodiev and Alijan Ibragimov. Mr Ibragimov died in February 2021.

Dechert took over an internal investigation initiated by ENRC in 2010 into alleged corruption by company officials in Kazakhstan and later in Africa. ENRC abruptly fired Dechert on 27 March 2013, just before it was due to report to the SFO about its activities in Africa. In April 2013, the SFO launched a formal corruption investigation into ENRC.

—

For further information, please contact:

Anneke Van Woudenberg, Executive Director of RAID, on (44) 77 11 66 4960 or [email protected]; twitter @woudena

Jessica Ni Mhainin, Policy and Campaigns Manager of Index on Censorship, [email protected]

The organisations who signed this statement are:

- Index on Censorship

- Rights and Accountability in Development (RAID)

- Human and Environmental Development Agenda (HEDA)

- Blueprint for Free Speech

- Corner House

- OBC Transeuropa

- Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

- IFEX

- Justice for Journalists Foundation (JFJ)

- European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF)

- Transparency International UK (TI-UK)

- PEN International

- ARTICLE 19

- Global Witness

- Spotlight on Corruption

- RECLAIM

- Whistleblowing International Network (WIN)

- The Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation

- Rainforest Rescue (Germany)

- Mighty Earth

- Publish What You Pay UK

- English PEN

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Jun 2021 | Belarus, China, Hong Kong, News and features

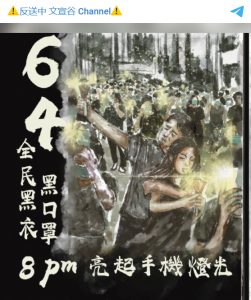

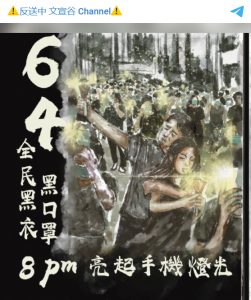

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

It shows crowds of young Hong Kongers, all dressed in black, at a protest, holding their smartphones aloft like virtual cigarette lighters from a Telegram channel called HKerschedule.

The image is an invitation for young activists to congregate and march to mark the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre on 4 June. Wearing black has been a form of protest for many years, which has led to suggestions that the authorities may arrest anyone doing so.

Calls to action like this have migrated from fly posters and other highly visible methods of communication online.

Secure messaging has become vital to organising protests against an oppressive state.

Many protest groups have used the encrypted service Telegram to schedule and plan demonstrations and marches. Countries across the world have attempted to ban it, with limited levels of success. Vladimir Putin’s Russia tried and failed, the regimes of China and Iran have come closest to eradicating its influence in their respective states.

Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services, are crucial for those intending to organise protests in countries where there is a severe crackdown on free speech. Myanmar, Belarus and Hong Kong have all seen people relying on the services.

It also means that news sites who have had their websites blocked, such as in the case of news website Tut.by in Belarus, or broadcaster Mizzima in Myanmar, have a safe and secure platform to broadcast from, should they so choose.

Belarusian freelance journalist Yauhen Merkis, who wrote for the most recent edition of the magazine, said such services were vital for both journalists and regular civilians.

“The importance of Telegram has grown in Belarus especially due to the blocking of the main news websites and problems accessing other social media platforms such as VK, OK and Facebook after August 2020,” he said.

“Telegram is easy to use, allows you to read the main news even in times of internet access restrictions, it’s a good platform to quickly share photos and videos and for regular users too: via Telegram-bots you could send a file to the editors of a particular Telegram channel in a second directly from a protest action, for example.”

The appeal, then, revolves around the safety of its usage, as well as access to well-sourced information from journalists.

In 2020, the Mobilise project set out to “analyse the micro-foundations of out-migration and mass protest”. In Belarus, it found that Telegram was the most trusted news source among the protesters taking part in the early stages of the demonstrations in the country that arose in August 2020, when President Alexander Lukashenko won a fifth term in office amidst an election result that was widely disputed.

But there are questions over its safety. Cooper Quintin, senior security researcher of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit that aims to protect privacy online, said Telegram’s encryption “falls short”.

“End-to-end encryption is extremely important for everyone in the world, not just activists and journalists but regular people as well. Unfortunately, Telegram’s end-to-end encryption falls short in a couple of key areas. Firstly, end-to-end encryption isn’t enabled by default meaning that your conversations could be intercepted or recovered by a state-level actor if you don’t enable this, which most users are not aware of. Secondly, group conversations in Telegram are never encrypted [using end-to-end encryption], lacking even the option to do so, unlike other encrypted chat apps such as Signal, Wire, and Keybase.”

A Telegram spokesperson said: “Everything sent over Telegram is encrypted including messages sent in groups and posted to channels.”

This is true; however, messages sent using anything other than Secret Chats use so-called client-server/server-client encryption and are stored encrypted in Telegram’s cloud, allowing access to the messages if you lose your device, for example.

The platform says this means that messages can be securely backed up.

“We opted for a third approach by offering two distinct types of chats. Telegram disables default system backups and provides all users with an integrated security-focused backup solution in the form of Cloud Chats. Meanwhile, the separate entity of Secret Chats gives you full control over the data you do not want to be stored. This allows Telegram to be widely adopted in broad circles, not just by activists and dissidents, so that the simple fact of using Telegram does not mark users as targets for heightened surveillance in certain countries,” the company says in its FAQs.

The spokesperson said, “Telegram’s unique mix of end-to-end encryption and secure client-server encryption allows for the huge groups and channels that have made decentralized protests possible. Telegram’s end-to-end encrypted Secret Chats allow for an extra layer of security for those who are willing to accept the drawbacks of end-to-end encryption.”

If the app’s level of safety is up for debate, its impact and reach is less so.

Authorities are aware of the reach the app has and the level of influence its users can have. Roman Protasevich, the journalist currently detained in his home state after his flight from Greece to Lithuania was forcibly diverted to Minsk after entering Belarusian airspace, was working for Telegram channel Belamova. He previously co-founded and ran the Telegram channel Nexta Live, pictured.

Nexta’s Telegram page

Social media channels other than Telegram are easier to ban; Telegram access does not require a VPN, meaning even if governments choose to shut down internet providers, as the regimes in Myanmar and Belarus have done, access can be granted via mobile data. Mobile data is also targeted, but perhaps a problem easier to get around with alternative SIM cards from neighbouring countries.

People in Myanmar, for instance, have been known to use Thai SIM cards.

The site isn’t without controversy, however. Its very nature means it is a natural home for illicit activity such as revenge porn and use by extremists and terror groups. It is this that governments point to when trying to limit its reach.

China’s National Security Law attempts to censor information on the basis of criminalising any act of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with external forces, the threshold for which is extremely low. It has a particular impact on protesters in Hong Kong. Telegram was therefore an easy target.

In July 2020, Telegram refused to comply with Chinese authorities attempting to gain access to user data. As they told the Hong Kong Free Press at the time: “Telegram does not intend to process any data requests related to its Hong Kong users until an international consensus is reached in relation to the ongoing political changes in the city.”

Telegram continues to resist calls to share information (which other companies have done): it even took the step of removing mobile numbers from its service, for fear of its users being identified.

Anyone who values freedom of expression and the right to protest should resist calls for messaging platforms like Telegram to pull back on encryption or to install back doors for governments. When authoritarian regimes are cracking down on independent media more than ever, platforms like these are often the only way for protests to be heard

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.