22 Oct 2025 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Scotland, United Kingdom

Banned Books Week UK was revived and celebrated across the nation recently, and it spawned an important conversation in Scotland about the conflict between inclusivity and intellectual freedom.

I headed to Scottish Parliament for an event run by CILIPS (the leading professional body for librarians in Scotland), sponsored by the SNP MSP Michelle Thomson. The discussion in question: libraries, intellectual freedom and culture wars.

How do librarians create a collection that is welcoming to their community, and balance it with books that challenge ideas or might be unpopular? There are questions to ask about intellectual freedom, but also moral obligations. What to do, for example, if someone walks into a library and wants to see a copy of Mein Kampf?

“At times of polarised views, it’s vital that we protect intellectual freedom,” said Shelagh Toonen, an award-winning school librarian and the vice president of CILIPS.

She was clear – libraries should have full control over their collections and access. They already look at the appropriateness of books for particular age groups, and the whole aim of a school library is to foster curiosity and resilience.

Sat beside Toonen was Cleo Jones, the former CILIPS president and libraries development manager for City of Edinburgh Council. She described how there’s recently been a strong push for developing knowledge around equality, including anti-racism training for staff, and she’s seen a positive impact. But there can be a tension with intellectual freedom. Staff need training around this too, she said.

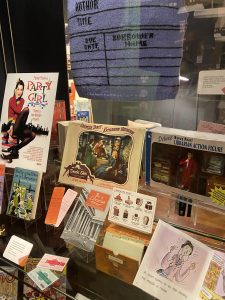

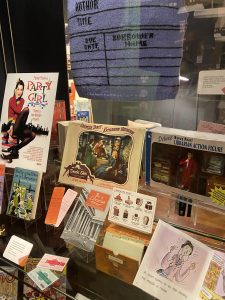

The Dear Library exhibition at the National Library of Scotland. Photo: Katie Dancey-Downs

Being a librarian was once considered a non-political role. Certainly, in the Dear Library exhibition just a short walk from Parliament in the National Library of Scotland, all the librarian stereotypes are on full display – a librarian action figure wearing glasses, a modest outfit and finger poised in the shush position, for example. But today, this role has suddenly become highly political, according to the panel. Managing sensitivities is a tough job, and is only getting tougher.

Steven Buchanan, professor of Communications, Media and Culture at the University of Stirling, put this into perspective with a discussion on book challenges in both the USA and the UK. He described how staff are being put under enormous pressure and are worried how things could escalate. Toonen and Jones have both been at the sharp end of this.

“It happened to me in my own school. A parent put in a letter of complaint because I had the book,” Toonen said of British writer Juno Dawson’s This Book is Gay, a book written for young people about the LGBTQ+ experience, and which has been one of the most banned books in the USA. Index research found that it has also been removed from some schools in the UK.

“If we remove books from our shelves how are young people going to see themselves represented?” Toonen asked, adding: “Two young people have come out to me in the school library, because it’s a safe space.”

For Jones, the event that caused a public stir was a drag queen story hour reading that her library held online during the Covid-19 pandemic. She described a staggering level of abuse directed towards staff, which mostly came from the USA.

“The number of positive comments far outweighed the negative, but three to four years later we’re still dealing with the fallout,” she said. They are still receiving letters, still instructing lawyers and some people involved in the event got major threats, she said.

Jones described how they had checked thoroughly that the drag queen was indeed a children’s entertainer. But that did not protect them from attacks. With so much time spent navigating the aftermath of a culture wars clash, Jones is concerned about the message this sends to librarians considering hosting similar events, and that they may well be put off. Her advice to fellow librarians – do all your checks (as she did), and then be completely transparent about this work, up front.

Challenges to collections have been easier to resist, she said. The more difficult and complicated fight is public spaces and displays, as the drag queen story hour lesson perfectly illustrates.

So too does an example from the National Library of Scotland, in the exhibition Dear Library. The display has been at the centre of a recent culture war clash, when the book The Women Who Wouldn’t Wheesht was not included, despite garnering enough votes - four - to be included as one of Scotland’s favourite books for the purposes of the exhibition. The book, a series of essays, is written by gender critical women detailing their political fight against the SNP leadership and the Scottish government which tried to introduce gender self ID laws (eventually blocked by Westminster). The book was still available in the library’s reading room, but deliberately left out of the exhibition due to staff concerns that it could cause harm.

Photo: Katie Dancey-Downs

The library faced a backlash for the decision which we wrote about at Index and later added the book to the exhibition. It is now there, on a double-sided row of shelves inviting people to look at the books, beneath front-facing copies of Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting and Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. The debate about sensitivities in library collections is clearly going nowhere, and the clash between trans rights and gender critical voices is a particularly polarising issue, especially in Scotland.

Challenges to free expression are nothing new. The difference now, the panel argued, is the rise of social media fuelling the culture wars. Suddenly, someone far away can learn about a decision in a library in Scotland.

“It feels heavier now,” said CILIPS president David McMenemy, and that’s because of social media.

Campaigns for books to be banned in the UK have been less organised than in the USA, where co-ordinated right-wing groups like Moms for Liberty have taken the lead. But Alastair Brian, the fact-checking lead for Scottish investigative journalism platform The Ferret, believes it is only a matter of time before that changes.

“There are certain groups in Scotland trying to put pressure on,” he said, specifically around books that the groups consider ideological. “In the US the way this has been applied is by singling people out. That definitely has a huge chilling effect.”

The question now is how libraries navigate these challenges, which are certainly not going away, and more likely will increase. Librarians need advocacy and funding, the panel said, and for MPs to oppose obvious censorship attempts.

Beyond this, McMenemy added, there is a problem with politicians finding profit in making everyone angry, and it is something he urged them to stop embracing.

Ultimately, the panel saw a strong need for open conversations where intellectual freedom, culture wars and sensitivities clash – and that means listening, as well as speaking. As Toonen told the room: “The best solution is always dialogue.”

21 Oct 2025 | News

Today marks the fifth Global Encryption Day.

Organised by the Global Encryption Coalition (GEC), a network of 466 civil society organisations, companies, and individual cybersecurity experts from 108 countries, Global Encryption Day aims to draw global attention to the risks of rushing through legislation to add technological “back doors” to encrypted messaging services like WhatsApp and Signal as well as cloud-based data services.

In democratic countries, the reasons for wanting to break encryption are well-intentioned – everyone wants to stop child sexual abuse and thwart terrorist attacks. Also, the security services are clearly interested in doing it. The problem is that there is no way to provide back-door access to encrypted data and communications without compromising the privacy and security of everyone who uses them.

Since it was established five years ago, the GEC has challenged legislative proposals for encryption in countries including Australia, Brazil, France, India, Sweden, Turkey, the UK, and the USA. In 2021, the Coalition successfully pressured the Belgian Government to scrap a proposed law to enable backdoor end-to-end encryption.

Index published a piece by the New European’s political editor James Ball recently on age verification. He wrote: “It is the case that since end-to-end encryption has become the default online, intelligence agencies are very keen to find ways to circumvent it – and to make the internet possible to monitor again.”

In the UK, the government is trying to break encryption. We wrote earlier this year about the government’s attempts to get access to Apple’s encrypted data. Our CEO Jemimah Steinfeld also wrote recently about threats to encryption in the Online Safety Act.

She wrote, “In a tolerant, pluralistic society, this may seem unthreatening, but not everyone lives in such a society. Journalists speak to sources via apps offering end-to-end encryption of messages. Activists connect with essential networks on them too. At Index we use them all the time.”

The Coalition is using a parrot (see above) as the emblem of Global Encryption Day. You may see posts on social media inviting users to “meet the parrot that knows too much. Curious, chatty, and ready to repeat everything it hears”.

Index believes encryption needs preserving. Help up support Global Encryption Day today.

20 Oct 2025 | Asia and Pacific, India, News, Pakistan

Kupwara, Kashmir

In a deserted lane in one of the countryside villages in a frontier district, Kupwara, a once well-known writer is now living a secluded life out of the spotlight. The walnut trees on one side provide shade and there are paddy fields over the fence on the other. For Zeeshan Ahmad, a writer who has written books on the political situation in the disputed region between two nuclear-armed states, India and Pakistan, life took a U-turn and he had to change his profession. Why? The repeal of Article 370 of the Constitution in August 2019, which gave India more control over the previously autonomous region of Jammu and Kashmir.

A visitor to Ahmad’s home will no longer find books strewn around, with pens and notepads piled on the windowsill in the writer’s' room. He has lain all the books aside and rarely displays them, as he is afraid of the consequences.

Similarly, Sheeraz, a scholar at Aligarh Muslim University in mainland India, is making new strides in the field of literature. However, for several years he has been keeping his manuscripts to himself. In a way, he is self-censoring after he was told by his editor that the authorities would not endorse his writing.

“It was on a hot, humid day in August during Covid-19 days in 2020 when I decided to write to my editor. The response hit me hard and I switched and stopped contributing.”

“The piece would not be accepted by the powers-that-be,” says Sheeraz about the work of fiction he had sent his editor.

The young writer has written a novel that was very well received by readers. His contribution to literature is acknowledged by the university professors where he completed his Master’s.

But fame comes with its own consequences.

His house has been raided many times by security forces, “searching my library and checking every nook and cranny of the house.”

“The raids and the surveillance were constant for me, following the ban on books,” says Sheeraz, who lives alone with his mother.

The process breaks

For Zeeshan, the ordeal began way back in the autumn of 2018. “There was a list of writers prepared by the authorities whom they felt were promoting secessionism in the valley,” recalls Ahmad.

This was at a time when Kashmir was run by a centrally appointed governor of the far-right Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP).

Many believe this was the beginning of control by Rashtriya Swamsewak Sangh, the parent organisation of the BJP – and it started its mission in full swing.

There was a delay when the BJP came to power in Kashmir in 2014 (following an alliance with the valley-based People’s Democratic Party), when an alliance was signed between the two which restricted the implementation of the BJP’s manifesto promises.

“As soon as the alliance ended, the campaign to do away with a separatist ideology began in the valley, with an iron-fist policy,” says Zeeshan, who at the time wrote columns for the leading daily.

Those on the list were raided at home and summoned to different police stations in the region. The Central Investigation Department of the J&K police and the National Investigation Agency began interrogating listed writers.

The constant surveillance was tiring. Zeeshan would wake up with a constant fear of being raided by the security forces.

“I do feel the wrath is felt more by those who were engaged in showing the true face of the occupation in the valley.”

“I felt it first-hand when our offices were sealed after one of the most highly reputed social organisations, Jamaat-e-Islami, started making education a reality for the poorer section of the society.” Helping the needy was banned by the authorities in 2019.

Irony engulfs the valley

Recently, while a first-of-its-kind book fair was being organised, Ishfaq, a retired teacher and poet, asked one of the panelists how free the press was.

The irony is that while the government of the day was celebrating the book fair and promoting a book-reading culture, the home department, on the sixth anniversary of the abrogation of special status, came up with a list of books to be banned in the region. The reasons cited were that these 25 books, which included those by internationally acclaimed authors, promoted secessionism. One of the most widely known writers on the list was Booker Prize-winner Arundhati Roy.

Immediately after the passing of the order, many booksellers were raided in different parts of Kashmir. The search operation was mainly carried out by local police in the central, south and northern areas of the Himalayan region. Booksellers were questioned about the banned books.

“We do not keep any books which are remotely connected to Jamaat or those written by separatists,” says a local bookseller in Handwara town in North Kashmir.

Glimpsing books which were once available everywhere is a rarity nowadays. Some dealers have even shifted to other types of trade, abandoning their cherished profession of bookselling.

When asked about the change, soft-spoken book-seller Lone Sahib said, “besides the change following the abrogation of Article 370, locals also fear carrying or having these books in their libraries. Since I was mostly selling literature that served the Urdu-speaking population and not those prescribed by schools, I had to switch.”

Out of love, Lone Sahib still keeps the sought-after books, but out of sight of passers-by.

‘Cultural invasion’

As changes to residency rights, domicile status and land ownership were brought in which met with little resistance by locals, the Lieutenant-Governor went further with his plan.

The main change that directly affected writers, especially those writing in Kashmiri, was the plan to change the script of the Kashmiri language from Nastaliq to Devangari.

The Kashmiri-speaking population, which is majority Muslim, feels that the change is a way of ‘Hinduising’ their culture.

Shakir, in his mid-20s and one of the young, budding writers who writes in the Kashmiri language, says this is a way of erasing the culture of the Muslim Kashmiris. “It has been done before and recent developments are scary for our identity and for future generations,” he says.

The proposal to have two scripts is not new. Kashmiri Hindus want Devangari to have the official stamp and they demand that it be declared a co-script for the language. Muslims on the other hand deem Devangari.to be an assault on their identity.

Way back in 2020, before four languages were added as the official languages besides Urdu, the spokesperson of the ruling National Conference tweeted that the order was an assault on their identity.

In one interview, a Member of Parliament from Kashmir, Ruhullah Mehdi, slammed the recent changes in Jammu and Kashmir as “cultural invasion” by the central government.

“In my eyes it is a cultural invasion by purpose and by design,” said Mehdi.

Changing roles

“We were expecting it. We had all the reason to believe that we would be asked to pack and leave,” recollects Zeeshan Ahmad.

On 1 March 2019, Zeeshan reached his office as usual. “However, upon arrival, we found our office sealed and security personnel manning the compound. We were asked to leave.” For nearly seven months he remained out of work and his laptop, once a prized asset, is now shoved in the back of the cupboard.

Clad in a traditional kameez shalwa and strolling outside talking to locals, Zeeshan is nevertheless optimistic about the situation.

“This phase of darkness too will pass. Nothing is permanent,” says Zeeshan in a joyful manner, his face beaming with pride.

He has not written for six years now.