20 Oct 2015 | About Index, Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Farida Shaheed

Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights

Mónica Pinto

Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers

David Kaye

Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression

Seong-Phil Hong

Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention

Special Procedures Branch

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

United Nations Office at Geneva

8-14 avenue de la Paix

1211 Geneva 10

Switzerland

Dear Special Procedure mandate holders,

We are writing to urge you to pay continuing attention to the arbitrary arrest, detention, and conviction of the Qatari poet Mohammed al-Ajami, widely known as Ibn al-Dheeb.

Al-Ajami’s case has been the subject of a December 2012 communication to the government of Qatar from the Special Rapporteur in the Field of Cultural Rights, the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, and the Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers1, discernable steps to address the issues set forth in the communication.

The arrest of Mohammed al-Ajami for the contents of his poetry is a violation of his right to freedom of expression and his right not to be arbitrarily deprived of liberty, and his conviction to 15 years in prison results further from a violation of his right to a fair trial. Amnesty International considers him a prisoner of conscience and he should be released immediately and unconditionally.

Various UN mechanisms have addressed al-Ajami’s case, as well as the human rights situation in Qatar more generally. Shortly before al-Ajami’s conviction in November 2012, the UN Committee against Torture criticized violations of due process by the State of Qatar in its consideration of the country’s second periodic report.2 The Committee recommended that Qatar “promptly take effective measures to ensure that all detainees, including non-citizens, are afforded, in practice, all fundamental legal safeguards from the very outset of detention.” It also expressed concern that persons detained under provisions of the Protection of Society Law (Law No. 17 of 2002), the Law on Combating Terrorism (Law No. 3 of 2004),and the Law on the State Security Agency (Law No. 5 of 2003) “may be held for a lengthy period of time without charge and fundamental safeguards, including access to a lawyer, an independent doctor and the right to notify a family member and to challenge the legality of their detention before a judge.” The Committee specifically cited Mohammed al-Ajami as an example of the fact that persons detained under these laws are often subject to incommunicado detention or solitary confinement. Though the Committee urged Qatar to amend its laws and ensure that fundamental safeguards are provided, Qatar has not taken any steps to address these concerns.

As noted above, al-Ajami’s case received additional attention from special procedures of the Human Rights Council through a joint communication issued on 21 December 2012, shortly after his original sentencing. The Special Rapporteurs in the Field of Cultural Rights, on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, and on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression expressed concern in a joint communication to the Qatari government that the arrest, detention, and sentencing of al-Ajami may have been “solely related to the peaceful exercise of his right to freedom of opinion and expression.” The Special Rapporteurs further noted concerns regarding the fairness of his trial and his treatment while in detention.3

On 14 February 2013, the Qatari government responded to the UN human rights experts by asserting that the government followed the proper procedures throughout al-Ajami’s case, and that the State “[keeps] in mind [its] obligations under international conventions and standards related to human rights and their 1 but the Government of Qatar has thus far not taken any implementation.”4 We believe that the Qatari government’s response did not accurately represent the administration of justice in this case, and the authorities took no further action of which we are aware.

On 8 January 2013, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) again voiced concern over the situation of Mohammed al-Ajami. The OHCHR’s spokesperson told reporters: “We are concerned by the fairness of his trial, including the right to counsel.” She additionally pointed to allegations that al-Ajami’s initial statement may have been tampered with in order to wrongly incriminate him.

In 2014, during a review of its human rights record in the context of the Universal Periodic Review, the Government of Qatar expressly rejected a recommendation to release Mohammed al-Ajami.5 At the same session, the government pointedly accepted a recommendation to “continue and strengthen relations with OHCHR.”6 We urge you to remind the Qatari government of this commitment.To the best of our knowledge, the United Nations has not taken any action on Mohammed al-Ajami’s case since his final appeal in October 2013. Thus, we respectfully ask that you continue to dedicate attention to his case and follow up on his arbitrary imprisonment, and insist that Qatar take corrective action to address the human rights violations that have been committed against him. We also ask that you raise these concerns with the Government of Qatar and follow up on the unaddressed recommendations set forth in past communications.

While we understand that his treatment while in prison has been generally acceptable, it remains the case, in our view, that he has been unfairly tried and convicted and, for that reason, this is a matter of an ongoing injustice.

Thank you for your time and consideration. Please do not hesitate to contact us if you need more information or clarifications.

Yours sincerely,

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain

Amnesty International

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information

Article 19

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

English PEN

FreeMuse

German PEN

Index on Censorship

International Federation for Human Rights

Irish PEN

PEN American Center

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders

Salam for Democracy and Human Rights

Split This Rock

Background

State security officials summoned Mohammed al-Ajami to a meeting on 16 November 2011. Upon arrival, authorities arrested him on suspicion of insulting the Emir of Qatar, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, and “inciting to overthrow the ruling system.”

The charges against al-Ajami related to a 2010 poem (“The Cairo Poem”) he had recited and which the Qatari authorities allege to have criticized the Emir. The poem nevertheless referred to the Emir as “a good man” and expressed “thanks” to him, and it formed part of a ‘call-and-response’ type of exchange that is a popular form of recitation. Al-Ajami recited it during a private gathering in Cairo in August 2010, after which one of the attendees posted a video of the event online.

On 29 November 2012, a lower court sentenced al-Ajami to life imprisonment following an unfair trial. The court reportedly heard testimony from three “poetry experts” employed by the government’s culture and education ministries, who testified that the poem represents an insult to the Emir of Qatar and his son.

On 25 February 2013, an appeals court reduced al-Ajami’s life sentence to 15 years. The Court of Cassation, Qatar’s highest court, upheld the 15-year sentence on 20 October 2013. Al-Ajami’s only remaining path to freedom is a pardon from the Emir.

The administration of justice in this case has been grossly flawed and has resulted in the arbitrary detention of Mohammed al-Ajami.

We believe that the legal basis of the charges against Mohammed al-Ajami – based in Articles 134 and 136 of the Qatari Penal Code – do not constitute internationally recognizable criminal offenses, unlawfully restrict the right to freedom of expression, and expressly contradict Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which states that: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

The authorities held him for a prolonged period of pre-trial solitary confinement. Following his arrest on 16 November 2011, Mohammed al-Ajami was held incommunicado for three months before he was allowed visits from his family. The first trial session was held in March 2012. Throughout the pre-trial investigations and despite petitions to the judge about his treatment, he was held in solitary confinement in a very small cell.

While he was being held in solitary confinement, authorities forced al-Ajami during interrogations to sign a document falsely stating that the poem was read in a public place in the presence of the press, according to information available to our organizations. In November 2011 and, reportedly, in subsequent court sessions, the lawyer of Mohammed al-Ajami asserted to the court that the poem was recited only in private.

We are concerned that the period of pre-trial detention without charge may have exceeded even Qatar’s own laws. Court documents indicate that the duration of pre-trial detention was within the limits provided for in Qatari law – which allows, in specific circumstances, up to six months detention before trial.

However, Mohammed al-Ajami’s former lawyer indicated in writing that the period of pre-trial detention exceeded the six months provided for in law. He indicated that charges had first been set out in June 2012.

Our organizations are unable to resolve this contradiction. We urge the Special Procedures branch to investigate these competing claims.

The trial was held behind closed doors without legal basis, and the court disregarded Mohammed al-Ajami’s right to choose his own legal representation by its imposition of another lawyer in place of the one he had chosen.

There was a lack of separation of investigative and decision-making powers, infringing on the principle of impartiality. According to information available to the signatories, Mohammed al-Ajami’s lawyer requested at the first session of the Doha Criminal Court that the presiding judge exclude himself from the case as he had conducted the pre-trial investigation. The judge rejected the lawyer’s request.

Al-Ajami was denied the right to be present at the trial. During the final hearing in October 2012, the court expelled Mohammed al-Ajami for being unruly. In his absence, and without measures taken to preserve the rights of the defense, the court proceeded to schedule the judgment to be held on 29 November 2012. Mohammed al-Ajami was not informed of the date. On the day of the verdict, the prison authorities did not bring Mohammed al-Ajami to court. Nevertheless, according to sources who informed al-Ajami’s former lawyer, the judge pronounced to the court “on the attendance of Mohammed al-Ajami, we have sentenced him to life.”

State security officials in Qatar continue to detain people in the absence of due process under laws that increasingly contribute to an environment that stifles and criminalizes expression. Mohammed al-Ajami is just one of the victims of this political reality. The international community should not ignore this violation of the right to freedom of expression or the failure to ensure fair trials in Qatar.

1 The letter, dated 21 December 2012, is referenced AL Cultural rights (2009) G/SO 214 (67-17) G/SO 214 (3-3-16); QAT 1/2012 and can be accessed at https://spdb.ohchr.org/hrdb/23rd/public_-_AL_Qatar_21.12.12_(1.2012).pdf

2 See: Committee against Torture: Concluding observations on the second periodic report of Qatar, adopted by the Committee at its forty-ninth session (29 October-23 November 2012), 25 January 2013, UN reference: CAT/C/QAT/CO/2

3 The letter, dated 21 December 2012, is referenced AL Cultural rights (2009) G/SO 214 (67-17) G/SO 214 (3-3-16); QAT 1/2012 and can be accessed at: https://spdb.ohchr.org/hrdb/23rd/public_-_AL_Qatar_21.12.12_(1.2012).pdf

4 Referenced 532 and QAT 1/2012, the letter can be accessed at: https://spdb.ohchr.org/hrdb/23rd/Qatar_14.02.13_(1.2012)_rescan.pdf

5 See paragraph 125.7 of the Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review – Qatar, issued by the Human Rights Council at its twenty-seventh session, dated 27 June 2014, is referenced A/HRC/27/15.

6 See paragraph 122.16 of the UPR report.

7 Oct 2015 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns, mobile

Today marks the 200th day of Bahraini prisoner of conscience Dr Abduljalil al-Singace’s protest. Since 21 March, Dr al-Singace has boycotted all solid food in protest of the treatment of inmates at the Central Jau Prison.

We, the undersigned NGOs, call for Dr al-Singace’s immediate and unconditional release, and the release of all political prisoners detained in Bahrain. We voice our solidarity with Dr al-Singace’s continued protest and call on the United Kingdom and all European Union member states, the United States and the United Nations to raise his case, and the cases of all prisoners of conscience, with Bahrain, both publicly and privately.

Dr al-Singace is a former Professor of Engineering at the University of Bahrain, an academic and a blogger. He is a 2007 Draper Hills Fellow at Stanford University’s Center on Democracy Development, and the Rule of Law. He has long campaigned for an end to torture and political reform, writing on these and other subjects on his blog, Al-Faseela. Bahraini Internet Service Providers continue to ban access to the blog and Dr al-Singace has suffered arbitrary detention and torture on multiple occasions. In June 2011, a military court sentenced Dr al-Singace to life imprisonment alongside other prominent protest leaders, collectively known as the ‘Bahrain 13’. He is considered a prisoner of conscience.

Dr al-Singace’s current protest began in response to the violent response of the Ministry of Interior to a riot that took place in the Central Jau Prison on 10 March 2015. Though only a minority of inmates participated in the riot, police collectively punished all detainees, subjecting them to beatings and other humiliating and degrading acts; depriving them of sleep and food; and denying them access to sanitation facilities. Dr al-Singace objects to the humiliating treatment and arbitrary detention to which prison authorities subject him and other prisoners of conscience. Additionally, Dr al-Singace rejects being labelled a criminal, as the government convicted him in 2011 on grounds relating to his peaceful exercise of his freedoms of speech and assembly.

Since Dr al-Singace began his protest, the international community has expressed concerns over the treatment of inmates at Bahrain’s largest prison complex and the condition of Dr al-Singace in particular. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights raised the issue of torture in Bahrain’s prisons in June. In July, the European Parliament passed a resolution on Bahrain calling for the unconditional release of prisoners of conscience, naming Dr al-Singace. The United States clarified its concerns regarding Dr al-Singace in August. The United Kingdom has also expressed its concerns over Bahrain.

In June 2015, NGOs launched a social media campaign for Dr al-Singace – #singacehungerstrike – alongside the University College Union. Since then, NGOs also organised protests outside the Bahrain Embassy, London, and the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office. On 27 August, the 160th day of Dr al-Singace’s protest, 41 NGOs issued an urgent appeal for the release of Dr al-Singace.

For over six months, Dr al-Singace has subsisted on water, fluids and IV injections for sustenance. He is currently interred at the prison clinic. Prison authorities seem to have finally begun to take notice of the international attention his case is attracting, as Dr al-Singace recently received treatment for a nose injury he suffered during his torture in 2011. He had waited over four years to receive such treatment. He also suffered damage to his ear as a result of torture, but has not received adequate medical attention for this injury.

According to Dr al-Singace’s family, the prison authorities will only transfer him to a civilian hospital for treatment if he agrees to wear a prisoner’s uniform, which he refuses to do on the grounds that he is a prisoner of conscience and not a criminal. Since the beginning of his protest, Dr al-Singace has lost 20 kilograms in weight. He is often dizzy and his hair is falling out. He survives on nutritional drinks, oral rehydration salts, glucose, water and an IV drip, and his family states that he is “on the verge of collapse.”

In the prison clinic, Dr al-Singace is not allowed to leave the building and is effectively held in solitary confinement. Though the clinic staff tends to him, he is not allowed to interact with other prison inmates and his visitation times are irregular. Authorities have now lifted an unofficial ban on Dr al-Singace receiving writing and reading materials, but access is still limited: prison staff have now given him a pen, but have still not allowed him access to any paper. The government has also denied Dr al-Singace permission to receive magazines sent to him in an English PEN-led campaign, despite promising to allow him to do so. He has no ready access to television, radio or print media.

We demand Dr Abduljalil al-Singace’s immediate release, and urge the international community to raise his case with Bahrain.

Signatories:

Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

ARTICLE 19

Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Institute of Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

English Pen

European – Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights (EBOHR)

Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR)

Index on Censorship

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

Lawyer’s Rights Watch Canada (LRWC)

No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ)

PEN Canada

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Scholars at Risk Network (SAR)

Sentinel Human Rights Defenders

The Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

The European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (ECDHR)

The Nonviolent Radical Party Transnational and Transparty (NRPTT)

For more and background information, read the previous statement here.

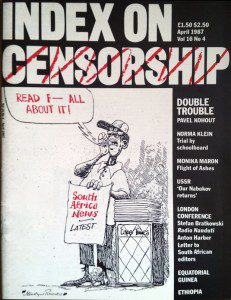

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by children’s book author Norma Klein, on the censorship of children’s books, taken from the spring 1987 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend the Banned books: controversy between the covers session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

I used to feel distinguished, almost honoured, when my young books were singled out to be censored. Now, alas, censorship has become so common in the children’s book field in America that almost no one is left unscathed. Some of the most conservative writers are being attacked; it’s reached a point of ludicrousness which, for me, was symbolised by my most recent encounter with ‘the other side’ in Gwinett county, Georgia, in April 1986.

Usually, my books are attacked for their sexual content. The two school board meetings I had attended in the early 1980s, one in Oregon, one in the State of Washington, had centred on two books for older teens, It’s Okay if You Don’t Love Me, a book about two 18- year-olds having a love affair, and Breaking Up, a novel about a 15-year-old girl who discovers her mother is gay. I might add parenthetically that these books have just been published in England for the first time by Pan Books in a new series aimed at teenagers, ‘Horizons’. Already, as in America, they are selling well and already, as in America, I have been told of indignant parents storming into bookstores and objecting to certain passages. It seems that things are not very different in other countries.

What was unusual about the Gwinnett county case was that the book selected to be attacked was one of my early ones, Confessions of an Only Child, about an eight-year-old girl. The offending sentence was one where the girl’s father is putting up wallpaper. Here it is in its entirety:

‘God damn it,’ Dad said as the wallpaper swung around and whacked him in the face.

When the paperback publisher of Confessions first heard of the attack, he attempted to defend the book in the following way:

Abrasive words are sometimes used by writers to add definition to a character or a story; they give the reader an understanding of the situation or kind of person speaking, but are not meant to be words which the reader should use or admire. It is our belief that the family relationships are so positive in this book that they far outweigh the use of realistic language.

My attacker, Theresa Wilson, a stunning blonde, had been heartened by her success in having another book she objected to, Deanie by Judy Blume, removed from the shelves. Her first attempt to remove my book was defeated by a 10-member review panel consisting of six parents, three teachers and a librarian. Ms Wilson claimed to have ‘stumbled’ upon the offending passage one afternoon while in the Beaver Ridge library looking for books that contain material to which she might object. In her thirties, she has no profession and, in a sense, being a censor has led to her becoming a local celebrity; she now, whether her attacks succeed or fail, appears regularly on TV and radio and is covered widely in local newspapers. The 10-member panel voted to keep Confessions on the shelves; only one person voted to keep it on a restricted shelf. ‘The consensus is that the book had literary merit for the age group intended,’ said principal Becky Hopcraft.

Incidentally, Ms Wilson said she didn’t object to my heroine’s mother saying, ‘Ye Gods,’ in the next line, because she does not believe ‘Gods’ refers to the Christian god. She wants every book containing the word ‘damn’ restricted from Gwinnett elementary schools. She cited a US Supreme Court ruling against hostility toward religion and said the use of God Damn in Confessions indicated a ‘hostility toward Christianity’.

All this, the initial attack on my book and its initial success in being retained on the shelves, helped to achieve an important result — the founding of a group called Gwinnett Citizens for Freedom in Education. Initially a small group, it now has nearly 500 members. Its president, Lorna Cox, said she was amazed at the diversity of the group’s members, proving that liberals in America are not, as some right-wingers insist, an elitist minority. ‘We’ve got people who didn’t graduate from high school,’ Ms Cox said, ‘college graduates, doctors, professionals, and people who aren’t even affiliated with a school but have a deep, burning desire to be involved in education.’ The group participates in workshops to learn more about censorship at the local and national levels and contacts school administrators each week to learn about potential book bannings.

As in the cases involving It’s Okay if You Don’t Love Me, and Breaking Up, my travel expenses to Georgia were paid by the author’s organisation, PEN. They have a Freedom to Read committee with a fund for cases like this. My own reason for attending these meetings is that I feel having the author appear and help argue the case not only gives heart to the local anti-censorship organisations involved, such as Gwinnett Citizens for Freedom in Education, but may focus national attention on the case. Perhaps it was co- incidental, but CBS did appear in the courtroom to cover the debate for a TV segment on ‘secular humanism’.

Before flying to Georgia I was interviewed by phone. I was quoted as saying, ‘I’m not a religious person… To me the phrase god damn has no more negative a connotation than the expression, Oh gosh. I added that I attributed the swing toward censorship in America to the conservative mood of the Reagan administration. When I arrived, I was told by two of my supporters that the negative reference to Reagan was a mistake. ‘Everyone is for him down here,’ they said. I have to add parenthetically that one of the reasons I write the kinds of books I do and am, perhaps ingenuously, surprised at the reaction they provoke, is due to the fact that I’ve lived all my life in New York City and know personally only liberal people. I’ve never met anyone who voted for Reagan; I am always amazed when the Republicans win an election. But it’s probably similar that in a two-week stay in London’ in the spring of 1986,1 didn’t meet anyone who was for Margaret Thatcher either. This may, however, give me a kind of inner freedom from certain restrictions, due simply to underestimating the power of the right.

The school board meeting I attended was crowded with supporters from both sides. It was conducted as a kind of mock trial. Both sides were allowed to question anyone from the other side about anything that was relevant to the case. I was pleased and relieved that every time Ms Wilson tried to bring the questioning around to my own personal religious beliefs, she was told that was not relevant to the book. In a perverse way I found her performance at the trial fascinatiing. She alternately flirted with, and tried to antagonise, the three-member school board which consisted of two men and a woman. Luckily for me, her case was weak and she overstepped the bounds of tolerance — even within a conservative, religious community — by telling the school board members that if they didn’t ban my book, they would, on Judgment Day, go straight to Hell. ‘One day each and every one of you will stand before God almighty and you will answer to how’you believe, how you voted, how you stand.’ Evidently this threat did not frighten anyone sufficiently.

The closest Ms Wilson got to making me come forward and state my personal beliefs was when she asked if I considered myself to be ‘above God’. I responded, ‘I assume that’s a rhetorical question.’ She laughed nervously and said she didn’t know what ‘rhetorical’ meant.

Confessions of an Only Child is about a family in which the mother gets pregnant and loses her baby. It shows how this affects the heroine who was enjoying her only child status. In deciding that Confessions had ‘redeeming educational value’, one of the board members, Louise Radloff, stated, ‘I think this book has much literary merit and it shows an open discussion within the family’. I had argued in my presentation that I felt that books could be an avenue to open discussion… a way to bring parents and children closer together, that simply having a book available was not forcing it on anyone.

What amazed me, though, was that in their closing remarks, though each school board member re-iterated the literary values of my book, all three said that, indeed, the phrase ‘God damn’, was offensive and should have been left out. One board member said he, thank heaven, had never used that word. Another said he had used it once, at the age of 10 and had been beaten so severely by his parents for this that he had never used it again. I am utterly unable to judge the sincerity of these remarks. What I did feel was the pressure on everyone living in these suburban communities to conform to what is felt to be a general set of beliefs. People are terribly afraid to come out and say they are feminists, atheists, or even, God forbid, Democrats.

In a sense this is a success story. Not only will my book remain on the shelves, but the Gwinnett Citizens for Freedom in Education feel heartened that the positive publicity they received will help them in future battles. But Theresa Wilson is, seemingly, not daunted. She’s already after another book, Go Ask Alice. ‘I don’t love publicity,’ she said when interviewed on a local radio show the day after the hearing. ‘I love showing the glory of God.’ Sadly, even the local people who are against her regard her as good copy. Although she had lost her case, she was brought forward to be on the radio show with me and most of the time was spent, not debating the issues involved, but in baiting her with peculiar call-in questions from the audience. What a pity. But still, no matter how absurd and tiny this one case is, I feel I would do it again for my own books and would encourage other authors to do the same. Passivity and inaction only encourages censorship groups even more. I think now they are beginning to realise they will, at least, have a fight on their hands.

Reporting the Third World

World leaders, or their top ministers, in an effort to arrive at something we call ‘balanced coverage’. Most Third World leaders feel you are either for ’em or against ’em and there is not much middle ground to walk upon. Some, as in Saudi Arabia, just don’t want to talk to the Western press. I can remember one visit to the Saudi kingdom in early 1981 when four American correspondents — from the New York Times, Time magazine, the Associated Press, and myself from The Washington Post — jointly applied for an interview with either King Khalid or Crown Prince Fahd. Each of us knew it was unlikely either would bother with an interview for just one publication, but here was a broad segment of the US print media asking collectively for an interview. After waiting around for two weeks, we collectively gave up and left.

One major problem for American correspondents is the near total ignorance of Third World leaders about how the Western media work and how to use them for their own ends. While the correspondent may regard his or her request for an interview with a leader or top minister as a chance to air their views, they seem to look upon it as a huge favour which they are uncertain will be rewarded in any way.

Other forms of indirect censorship come in control over a correspondent’s access to the story or means of communication. Israel restricted, or at least tried to restrict, access to southern Lebanon after its invasion in June 1982 to those it felt were sympathetic to its cause or important to convince of its view. The policy never really worked because correspondents could always get into Israeli-occupied territory from the north through one back road or another. But it got more difficult as time went on. The Israeli attempt at restricting access to southern Lebanon was hardly the worst example of this kind of censorship I experienced in nearly two decades of working in the Third World, however. Covering the war between Iran and Iraq was, and remains, far more difficult. In four years, I never once got a visa to Iran. I got to Baghdad several times, but imagine my surprise the first time customs officials seized my typewriter at the airport and told me I would have to get special permission from the Information Ministry to bring it in. (At the airport in Tripoli there was a roomful of confiscated typewriters the last time I visited there in September 1984.) Whether one was allowed to the Iraqi war front depended on either an Iraqi victory or a lull in the war. As for permission to travel into Iraqi Kurdistan, it was never granted to any Western correspondent I can think of in the four-to-five years I was covering the Middle East.

The other game Iraqi information officials play is attempting to censor your coverage of the war. When I first went there, there was a Ministry of Information official sitting at the hotel who had to okay your copy or you could not send it out by phone or telex. This kind of direct censorship of copy was rare in my experience, however. Other than Israel, where military news is supposed to pass through the censor’s office, and Iraq and Libya, I can think of no examples where I had to submit my copy before sending it.

Are the techniques of indirect censorship getting worse? In the areas of the world where I have worked, I am not sure. If Syria has become worse, Iraq is probably better today. Egypt has definitely got better, and so had Kuwait until recently. Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has restricted access to a far greater degree in the past two years, and Bahrain has become more sensitive. South Africa has taken a turn for the worse. Countries that were always difficult to cover, such as Zaire, Malawi, Ethiopia and Angola, remain more or less the same.

As economic problems have got worse or rulers have felt a greater threat to their regimes, Third World governments seem to be tightening up when it comes to outside press coverage.

If this is indeed the underlying principle governing the degree of press censorship, then the problem may be more cyclical than linear, getting worse or better according to the political and economic health of a country or the special challenges it is facing at that time.

Who believes it?

‘That is how the theory goes: Restrict the press to supportive comment, and a country’s life will be calmer and better. But experience and reason suggest that the opposite will happen. Faulty government policies, if they are not subject to real criticism, grow worse. Autocrats become more autocratic. Can anyone believe that repression of criticism leads to efficiency in a society, to new ideas?’

Anthony Lewis, The New York Times, February 1987

© Norma Klein and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the spring 1987 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

18 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.01 Spring 2015

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is and article by Ismail Einashe on television journalist Temesghan Debesai’s escape from Eritrea, taken from the spring 2014 issue. This article is a great starting point for those planning to attend the A New Home: Asylum, Immigration and Exile in Today’s Britain session at the festival.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

Television journalist Temesghen Debesai had waited years for an opportunity to make his escape, so when the Eritrean ministry of information sent him on a journalism training course in Bahrain he was delighted, but fearful too. On arrival in Bahrain, he quietly evaded the state officials who were following him and got in touch with Reporters Sans Frontières. Shortly after he met officials from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees who verified his details. He then went into hiding for two months so the Eritrean officials in Bahrain could not catch up with him and eventually escaped to Britain.

Debesai told no one of his plans, not even his family. He was concerned he was being watched. He says a “state of paranoia was everywhere” and there was no freedom of expression. Life in Eritrea, he explains, had become a “psychological prison”.

After graduating top of his class from Eritrea’s Asmara University, Debesai became a well-known TV journalist for state-run news agency Erina Update. But from 2001, the real crackdown began and independent newspapers such as Setit, Tsigenai, and Keste Debena, were shut down. In raids journalists from these papers were arrested en masse. He suspects many of those arrested were tortured or killed, and many were never heard of again. No independent domestic news agency has operated in Eritrea since 2001, the same year the country’s last accredited foreign reporter was expelled.

The authorities became fearful of internal dissent. Debesai noticed this at close hand having interviewed President Afwerki on several occasions. He describes these interviews as propaganda exercises because all questions were pre-agreed with the minister of information. As the situation worsened in Eritrea, the post-liberation haze of euphoria began to fade. Eritrea went into lock-down. Its borders were closed, communication with the outside world was forbidden, travel abroad without state approval was not allowed. Men and women between the ages of 18 and 40 could be called up for indefinite national service. A shoot-to-kill policy was put in operation for anyone crossing the border into Ethiopia.

Debesai felt he had no other choice but to leave Eritrea. As a well-known TV journalist he could not risk walking across into Sudan or Ethiopia, so he waited until he got the chance to leave for Bahrain.

Eritrea was once a colony of Italy. It had come under British administrative control in 1941, before the United Nations federated Eritrea to Ethiopia in 1952. Nine years later Emperor Haile Selassie dissolved the federation and annexed Eritrea, sparking Africa’s longest war. This long bitter war glued the Eritrean people to their struggle for independence from Ethiopia. Debesai, whose family went into exile to Saudi Arabia during the 1970s, returned to Eritrea as a teenager in 1992, a year after the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front captured the capital Asmara.

For Debesai returning to Asmara had been a “personal choice”. He wanted to be a part of rebuilding his nation after a 30-year conflict, and besides, he says, life in post-war Asmara was “socially free”, a welcome antidote to conservative Saudi life. Those heady days were electric, he says. An air of “patriotic nationalism” pervaded the country. Women danced in the streets for days welcoming back EPLF fighters. Asmara had remained largely unscathed during the war thanks to its high mountain elevation. Much of its beautiful 1930s Italian modernist architecture was intact, something Debesai was delighted to see.

But those early signs of hope that greeted independence quickly soured. By 1993 Eritreans overwhelmingly voted for independence, and since then Eritrea has been run by President Isaias Afwerki, the former rebel leader of the EPLF. Not a single election has been held since the country gained independence, and today Eritrea is one of the world’s most repressive and secretive states. There are no opposition parties and no independent media. No independent public gatherings or civil society organisations are permitted. Amnesty International estimates there are 10,000 prisoners of conscience in Eritrea, who include journalists, critics, dissidents, as well as men and women who have evaded conscription. Eritrea is ranked the worst country for press freedoms in the world by Reporters Sans Frontières.

The only way for the vast majority of Eritreans to flee their isolated, closed-off country is on foot. They walk over the border to Sudan and Ethiopia. The United Nations says there are 216,000 Eritrean refugees in Ethiopia and Sudan. By the end of October 2014, Sudan alone was home to 106,859 Eritrean refugees in camps at Gaderef and Kassala in the eastern, arid region of the country.

In Ethiopia, Eritrean refugees are found mostly in four refugee camps in the Tigray region, and two in the Afar region in north-eastern Ethiopia.

During the first 10 months of 2014, 36,678 Eritreans sought refuge across Europe, compared to 12,960 during the same period in 2013. Most asylum requests were to Sweden (9,531), Germany (9,362) and Switzerland (5,652). The UN says the majority of these Eritrean refugees have arrived by boat across the Mediterranean. The majority of them are young men, who have been forced into military conscription. All conscripts are forced to go to Sawa, a desert town and home to a military camp, or what Human Rights Watch has called an open-air prison. Many young men see no way out but to leave Eritrea. For them, leaving on a perilous journey for a life outside their home country is better than staying put. The Eritrean refugee crisis in Europe took a sharp upward turn in 2014, as the UNHCR numbers show. And tragedies, like the drowning of hundreds of Eritrean refugees off the Italian island of Lampedusa in October 2013, demonstrate the perils of the journey west and how desperate these people are.

Even when Eritrean refugees go no further than Sudan and Ethiopia, they face a grim situation. According to Lul Seyoum, director of International Centre for Eritrean Refugees and Asylum Seekers (ICERAS), Eritrean refugees in a number of camps inside Sudan and Ethiopia face trafficking, and other gross human rights violations. They are afraid to speak and meet with each other. She said, that though information is hard to get out, many Eritreans find themselves in tough situations in these isolated camps, and the situation has worsened since Sudan and Eritrea became closer politically.

Eritrea had a hostile relationship with Sudan during the 1990s. It supported the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, much to the anger of President Al Bashir who was locked in a bitter war with the people of now-independent South Sudan. Today tensions have eased considerably, and President Afwerki has much friendly relations with Sudan to the detriment of then tens of thousands of Eritrean refugees in Sudan.

A former Eritrean ministry of education official, who is a refugee now based in the UK and who does not want to be named because of safety fears, believes there’s no freedom of expression for Eritreans in Ethopian camps, such as Shimelba.

The official says in 2013 a group of Eritrean refugees came together at a camp to express their views on the boat sinking near Lampedusa and they were abused by the Ethiopian authorities who then fired at them with live bullets.

Seyoum believes that the movement of Eritreans in camps in Ethiopia is restricted. “The Ethiopian government does not allow them to leave the camps without permission,” she says. Even for those who get permission to leave very few end up in Ethiopia, instead through corrupt mechanisms are trafficked to Sudan. According to Human Rights Watch, hundreds of Eritreans have been enslaved in torture camps in Sudan and Egypt over the past 10 years, many enduring violence and rape at their hands of their traffickers in collusion with state authorities.

Even when Eritreans make it to the West, they are still afraid to speak publicly and many are fearful for their families back home. Now based in London, Debesai is a TV presenter at Sports News Africa. As an exile who has taken a stance against the regime of President Afewerki, he has faced harassment and threats. He is harassed over social media, on Twitter and Facebook. Over coffee, he shows me a tweet he’s just received from Tesfa News, a so-called “independent online magazine”, in which they accuse him of being a “backstabber” against the government and people of Eritrea. Others face similar threats, including the former education ministry official.

For this piece, a number of Eritreans said they did not want to be interviewed because they were afraid of the consequences. But Debesai said: “It takes time to overcome the past, so that even for those in exile in the West the imprisonment continues.” He adds: “These refugees come out of a physical prison and go into psychological imprisonment.”

© Ismail Einashe and Index on Censorship