16 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

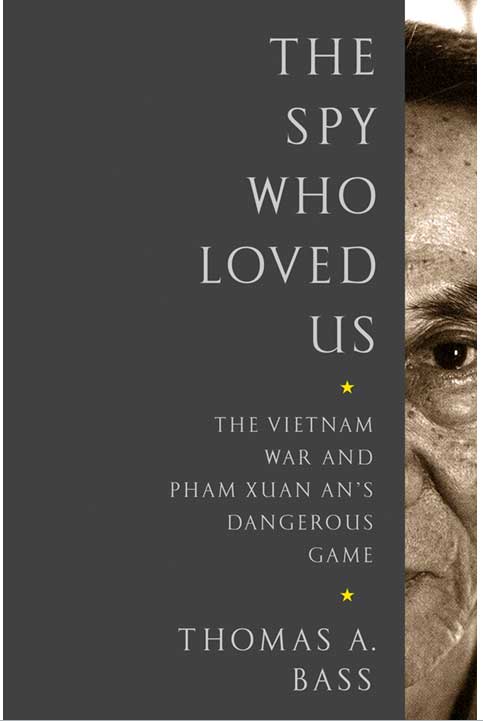

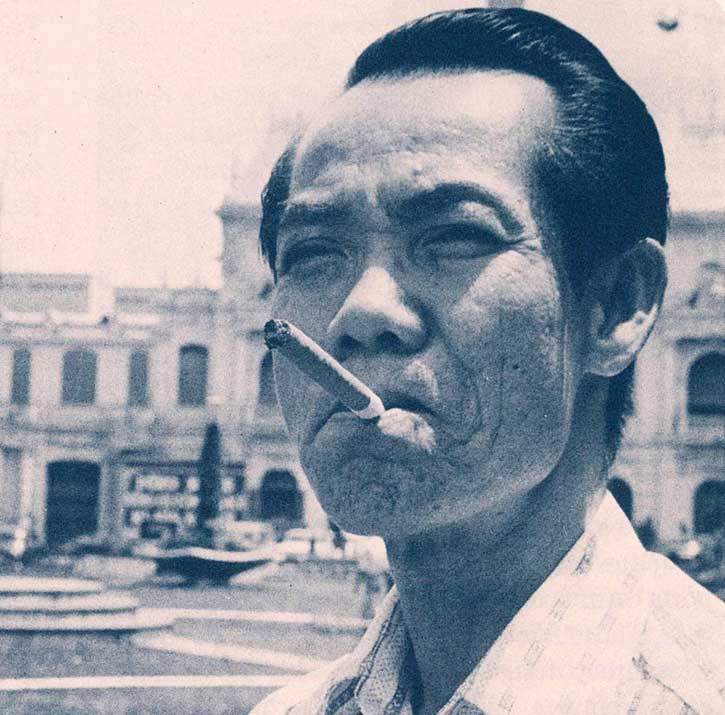

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

I meet Bao Ninh again in 2014, when I am visiting Hanoi after the publication of The Spy Who Loved Us. I arrive at his house at seven in the evening, again with a translator and an assistant who wish to remain anonymous. Also with me are my twin sons, who will be celebrating their twenty-first birthdays in Hanoi. The evening heat is wrapped around us like a clay pot baking in Hanoi’s summer oven, Ninh uncorks a bottle of Chilean red wine and welcomes us into a living room that looks cheerier than the last time I was here, with the neon tubes on the wall not quite so pallid and a new sofa angled next to his chair, which is placed looking out toward the front door.

Ninh’s wife, Thanh, has skipped her exercise class to come home and cook dinner for us. A secondary school teacher with a wary smile, she has fried up a few dozen egg rolls, which are laid out on the coffee table along with bowls of hot sauce and nuoc mam fish sauce. I have brought soft drinks, pastries, and beer. Ninh urges us to begin eating, and my sons tuck into the meal. Our host sticks to drinking wine while Thanh flutters in and out of the kitchen. We chat about Ninh’s son, who now works in Saigon for Vina Capital, an investment company.

“It’s a different world from the one I know,” he says. He himself has retired from writing for Bao Van Nghe Tre, the literary journal for which he used to pen a weekly column. Now he works for himself, rising at midnight to write through the night, and then shredding his work at dawn, or so he says. Even relaxed over a glass of wine, Ninh is reticent about discussing his work.

When I broach the subject of his two unpublished novels, Ninh tells me that I have the wrong titles for his books and that he never wrote one of them anyway, except for a short piece that was published somewhere (he can’t remember where). Ninh has a way of shaking his head from side to side and grinning under his moustache when he disagrees with you or wants to avoid talking about something. So forget about discussing censorship, internal exile, or other sensitive subjects. He is not going to retell his story about how a thousand South Vietnamese POWs were brought North to impregnate a thousand widows in Ho Chi Minh’s natal village—even if this tale summarizes in one allegorical masterstroke the history of postwar Vietnam.

Ninh complains about the heat, and then he starts complaining about the Chinese, which is currently the number one topic in Vietnam. On April 30th—Vietnam’s national holiday for marking the unification of north and south Vietnam, the day you pick if you want to kick your enemy in the nuts and then spit in his eye—China moved a billion-dollar oil rig into Vietnam’s offshore waters and started drilling for oil. China surrounded the rig with an armada of ships and chased off any Vietnamese boats that dared to approach. The Chinese rammed Vietnamese coast guard vessels. They sank fishing boats. They fired water cannons that looked like medieval dragons spouting blue flames. As silly as these dragon boats may have looked, they proved quite effective at destroying electrical gear on the Vietnamese boats that were forced to flee.

Following this Chinese aggression, thirty thousand Vietnamese rose up in protest and started sacking Chinese textile factories around Saigon. Mobs burned at least fifteen companies and damaged another five hundred before police got the area locked down. Speculation abounds about the cause of these riots. They were orchestrated by government agents or by anti-government agents or by criminal gangs or by the Chinese themselves, since the looted factories turned out to be owned by Taiwanese and Koreans.

“We are experts on China,” says Ninh. “We just don’t talk about it. They are always smiling, but their smile is dangerous. They will be the nightmare of the world. By 2030, China will be far stronger than the United States. Our civilization will be threatened. I’m pessimistic. I see no light at the end of the tunnel,” he says, using a phrase employed by Richard Nixon during the Vietnam war. “I see only darkness,” Ninh says. “The younger generation should prepare. I feel a black cloud coming. Danger is approaching.”

Now that the red wine is gone, Ninh fills his glass with white and urges us to eat more egg rolls. Our host has a thatch of salt and pepper hair, now more salt than pepper, and a Fu Manchu moustache that gives his face the look of a window shuttered behind Venetian blinds. Wearing dark slacks and a white, short-sleeved shirt, he has kicked off his sandals and is cooling his feet on the linoleum as he settles back in his chair to ponder the dark cloud floating over Vietnam. It is quiet out on the street, save for the occasional motorbike rolling down the lane, but Ninh tells us how, during the day, he hears a constant din from the loudspeaker attached to a pole outside his door. The Party directives and propaganda become increasingly strident around holidays, the worst being April 30th, which commemorates the day in 1975 that Bao Ninh and his fellow soldiers captured Saigon.

“They talk about the old victories over and over again,” he says. “Even as a soldier I don’t like it. It’s like telling a beautiful girl she’s beautiful. She already knows she’s beautiful; so all you’re doing is annoying her. Next year, which marks the 40th anniversary of the end of the war, it’s going to be really annoying,” he says.

I have given Ninh a copy of my newly-published book. He keeps fingering it, flipping through the pages, stopping now and then to study a passage. “I don’t like intelligence agents and the police,” he says. “Maybe I’ll like them better after I read this.”

Ninh pours himself another glass of wine. “I never met Pham Xuan An,” he says. “He was a big general. I was just a soldier. Now that the government has made him a hero, they’ve started telling young people to act like him, which is really stupid. It’s like telling American teenagers they should grow up to be like Lyndon Johnson.”

Ninh stops to read the opening paragraph. “This is how you can tell if a translation is worth reading,” he says. “It looks pretty good.” Later he will send me an email praising the book and telling me how much he enjoyed reading it, even with the missing passages.

Ninh’s face is animated by the thick eyebrows that sweep over his black eyes. He windmills his hands through the air and slaps the back of his head. Then he pushes his hands in front of him like a surf swimmer heading for deep water. “The more we understand the Chinese the more we fear them,” he says. “Hitler was able to come to power because he was helped by Britain and France. They took care of him. The same is true with the United States and China. The Americans built up China’s industrial capacity. You moved your factories to China. You made the Chinese strong by doing business with them, but this strategy is going to fail in the end, just like it failed with Hitler.”

I nudge the conversation back to writing. “We have to follow the Communist Party line,” he says about censorship in Vietnam. “Every writer knows this. You’re hired for a reason; so don’t talk back. If you don’t accept the censorship system, then don’t be a writer.”

“They want to make Pham Xuan An into a political commissar,” he says. “This is why they censored your book. A good intelligence agent is like a priest. He keeps his secrets to himself.” The secrets of Pham Xuan An could be revealed only after the war and only selectively, after having been shaped into a heroic tale.

“For Vietnamese readers, a book without any cuts is a surprise,” says Ninh. “People will know where your book was cut. I prefer to read the printed version, but young people will go online to learn what you really wrote. This is becoming second nature for us, and soon we won’t have any printed books at all.”

He tells me he is writing a new novel, but he won’t say what it’s about. “We have to work quietly and not talk about it to anyone,” he says. “My time is over. I just write. I don’t publish.”

I ask him what Vietnamese writers I should be reading. “There is no generation of young writers,” he says. “There are just some individuals, one or two that I read.”

Next we talk about the movie that was being made of his novel. Film rights to The Sorrow of War were sold to a young American producer, Nicholas Simon, who also wrote the screenplay, but the project unraveled a few days before filming was to start. “We didn’t understand each other,” says Ninh. “We’re both stubborn people. He was young. He knew nothing about Vietnam. The script was so far from reality that it was ludicrous. I kept editing it, but it never got better. I yelled at him in Vietnamese. He yelled at me in English. The translator cried. Finally, the main investor, who was a friend of mine, fled after seeing our inability to get along. A movie has to be easy. My book is too hard to make into a movie.”

Before saying goodnight, Bao Ninh offers his final word on the subject of censorship. “Some guy who grew up as a peasant has the right to mess with your work? No one has the right to censor a book. When politics enters the room, ethics flies out the door. Other countries have laws protecting writers. In Vietnam, we have nothing. There are no rules to follow. The politicians make the rules.”

Part 12: The struggle

This eleventh installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 16, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Feb 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Statements, mobile, News and features, Statements

In January, Index on Censorship reported on the beginning of the trial of human rights activist Rasul Jafarov, who is being tried on spurious charges. The Azerbaijani embassy has written to Index on Censorship responding to that article. This is the Index response to the embassy.

Dear Ambassador Tahir Taghizadeh,

Thank you for your letter in response to our report on the beginning of the trial of human rights and democracy activist Rasul Jafarov.

In your letter, you wrote:

“In my country, human rights and fundamental freedoms are ensured in full compliance with the national and international commitments that Azerbaijan has subscribed to. No one is persecuted for his/her political views and activities as proved by Azerbaijan’s vibrant political process and free and diverse media.”

We beg to differ with your point of view.

Azerbaijan’s record on human rights and a free press has been discussed with great concern at the international level many times in recent years.

In March 2012, Index on Censorship joined with Article 19, Human Rights House Foundation, International Federation of Journalists, Media Diversity Institute, Norwegian Helsinki Committee, Reporters Without Borders and World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers to co-produce Running Scared: Azerbaijan’s Silenced Voices. The report opened with this stark warning: “The current state of freedom of expression in Azerbaijan is alarming, as the cycle of violence against journalists and impunity for their attackers continues; journalists, bloggers, human rights defenders and political and civic activists face increasing pressure, harassment and interference from the authorities; and many who express opinions critical of the authorities – whether through traditional media, online, or by taking to the streets in protest – find themselves imprisoned or otherwise targeted in retaliation.”

In December 2012, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe issued a monitoring report that included the comments that the “situation with regard to basic freedoms, including freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and freedom of association is preoccupying. The committee expresses its alarm at reports by human rights defenders and domestic and international NGOs about the alleged use of so-called fabricated charges against activists and journalists. The combination of the restrictive implementation of freedoms with unfair trials and the undue influence of the executive results in the systemic detention of people who may be considered prisoners of conscience. Alleged cases of torture and other forms of ill-treatment at police stations, as well as the impunity of perpetrators, raise major concern”.

In April 2013, the Human Rights Council of the United Nations work group issued its report from Azerbaijan’s universal periodic review. Among the recommendations were suggestions for improvements on human rights and more specifically freedom of expression:

• Ensure the full enjoyment of the right to freedom of expression in line with country’s international commitments (Slovakia)

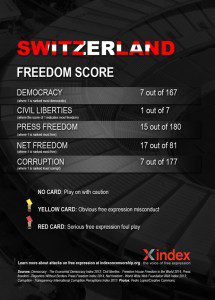

• Guarantee the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly particularly by allowing peaceful demonstrations in line with the obligations stemming from the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Switzerland);

• Put in place additional and fitting measures to ensure respect for freedom of expression and of the media (Cyprus);

• Ensure that Azerbaijani media regulations uphold diversity among media outlets, as per international standards and best practices (Cyprus);

• Expand media freedoms across print, online and, in particular, broadcast platforms, notably by ending its ban on foreign broadcasts on FM radio frequencies and eliminating new restrictions on the broadcast of foreign language television programs (Canada);

• Take effective measures to ensure the full realization of the right to freedom of expression, including on the Internet, of assembly and of association as well as to ensure that all human rights defenders, lawyers and other civil society actors are able to carry out their legitimate activities without fear or threat of reprisal (Czech Republic);

• Ensure that human rights defenders, lawyers and other civil society actors are able to carry out their legitimate activities without fear or threat of reprisal, obstruction or legal and administrative harassment (Sweden);

• Put an end to direct and indirect restrictions on freedom of expression and take effective measures to ensure the full realization of the right to freedom of expression and of assembly (Poland);

• Ensure the full exercise of freedom of expression for independent journalists and media, inter alia, by taking into due consideration the recommendations of the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights (Italy);

• Ensure that journalists and media workers are able to work freely and without governmental intimidation (Germany);

• Ensure that journalists and writers may work freely and without fear of retribution for expressing critical opinions or covering topics that the Government may find sensitive (Slovenia);

• Protect and guarantee freedoms of expression and association in order to enable human rights defenders, NGOs and other civil society actors to be able to conduct their activities without fear of being endangered or harassed (France);

• Strengthen measures to guarantee a safe and conducive environment for the free expression of civil society (Chile);

• Remove all legislative and practical obstacles for the registration, funding and work of NGOs in Azerbaijan (Norway);

• Ensure that all human rights violations against human rights defenders and journalists are investigated effectively and transparently, with perpetrators being promptly brought to justice, including pending unresolved cases requiring urgent attention (United Kingdom);

• Ensure prompt, transparent and impartial investigation and prosecution of all alleged attacks against independent journalists, ensuring that

the media workers do not face reprisals for their publications (Slovakia);

Though Azerbaijan has the modern legal framework in place to respond to these suggestions from the international community, the respect for the rule of law is sorely lacking.

In October 2013, Index on Censorship published Locking up free expression: Azerbaijan silences critical voices, which described the situation in your country in the run up to the presidential elections.

We wish that was the end of the story, that our insistence that Azerbaijan respect free of expression was based on outdated information or thoroughly implemented international recommendations.

But in 2014 the assault against journalists and human rights activists accelerated with detentions of well-respected individuals with international profiles and the temerity to speak some uncomfortable truths to the government of Azerbaijan.

These are just a few of the cases against journalists and human rights activists that we follow:

Anar Mammadli and Bashir Suleymanli

Anar Mammadli and Bashir Suleymanli — sentenced to 5.5 and 3.5 years respectively in May 2014 — are prominent human rights activists and founders of the Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Centre. They were arrested and jailed in 2013, following outspoken criticism of presidential elections in October 2013, despite international protests. Those are the same polls that invited election observers from the OSCE found lacking. On 29 September 2014, Mammadli was awarded the Václav Havel Award for Human Rights by the Council of Europe.

Arif and Leyla Yunus (Photo: HRHN)

Leyla Yunus — arrested 30 July 2014 — is the director of the Peace and Democracy Institute, which among other things works to establish rule of law in Azerbaijan. She has been charged with state treason (article 274 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan), large-scale fraud (article 178.3.2), forgery (article 320), tax evasion (article 213), and illegal business (article 192). On 18 February, her pre-trial detention was extended for another five months. Her husband Arif Yunus was arrested 5 August 2014. Arif Yunus is facing charges of state treason and fraud. Both have had their initial three month pre-trial detentions extended.

Human rights and democracy activist Rasul Jafarov (Photo: Melody Patry)

Rasul Jafarov — arrested 2 August 2014 — one of the initiators and coordinators of the campaign “Sing for Democracy” and “The Art of Democracy”, advocated for the rights of political prisoners, actively participated in the International Platform “Civil Solidarity.” He is accused of: tax evasion (Article 192), illegal business (Article 213) and malpractice (Article 308). The charges carry a possible sentence of 12 years.

Lawyer Intigam Aliyev

Intigam Aliyev — arrested 8 August 2014 — is a human rights defender and a lawyer specialized in defending rights of citizens in the European Court of Human Rights. He is charged with Articles 213.1 (tax evasion), 308.2 (malpractice) и 192.2 (illegal business) of the Criminal Code. Index was heartened to hear that Aliyev was at least allowed to sit with his lawyers in court on Feb 3.

Journalist Seymur Hezi

Seymur Hezi — arrested 29 August 2014 — works for independent newspaper Azadliq and host of the news programme “Azerbaijan Hour”. He is a member of the opposition Popular Front Party. Index reported on January 29 that Hezi was sentenced to a five-year prison sentence on charges of “aggravated hooliganism” on 29 January.

Emin Huseynov, journalist and human rights defender, director of the Azerbaijani Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS)

Emin Huseynov — went into hiding in August 2014 — is an internationally recognised human rights defender and leader of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS). IRFS is the leading media rights organisation in Azerbaijan and one of the main partner organisations of the Human Rights House Network in the country. Huseynov was charged with tax evasion, illegal business and abuse of authority after he went into hiding at the Swiss embassy. Florian Irminger, head of advocacy at the Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF), of which Index is a network member, called on Switzerland to continue to host Huseynov. “His location at the embassy is justified by the level of the repression in the country, the bogus charges brought against human rights defenders in Azerbaijan and the impossibility for them to defend themselves in court, due to the lack of independence of the judiciary and the harassment of their lawyers.”

Khadija Ismayilova

Khadija Ismayilova — arrested on 5 December — is an investigative journalist and radio host who is currently working for the Azerbaijani service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. She is a member of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. She was arrested under charges of incitement to suicide, a charge widely criticised by human rights organizations. Ismayilova is currently being supported by two petition campaigns by Index on Censorship and Reporters Without Borders. On 13 Feb, lawyer Fariz Namazly told Contact.az that new charges have been filed. According to him, Ismayilova is charged under the Article: 179.3.2 (large-scale embezzlement), 192.2.2 (illegal business), 213.1 (tax evasion) and 308.2 (abuse of power.) The charges carry a possible sentence of 12 years.

Award-winning newspaper Azadliq was forced to halt its print edition in July 2014 as its bank accounts were frozen. We reported on this in August 2014.

In September, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the human rights situation in your country.

In November, Nils Muižnieks, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, called his autumn 2014 mission to Azerbaijan one of the most difficult of his tenure. He wrote, “In late October I was in Azerbaijan, the oil-rich country in the South Caucasus, which just finished holding the rotating chairmanship of the 47-member Council of Europe. Most countries chairing the organisation, which prides itself as the continent’s guardian of human rights, democracy and the rule of law, use their time at the helm to tout their democratic credentials. Azerbaijan will go down in history as the country that carried out an unprecedented crackdown on human rights defenders during its chairmanship.”

You mention in your letter that individuals are not being arrested for their human rights work but it seems an astonishing coincidence that all these prominent human rights defenders should all be guilty of such an array of financial crimes. And that brings us full circle to the present. Since we received your letter, there have been several developments that we would like to brief you on:

On 29 January 2015, a provisional resolution before the CoE called attention to the cases of investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova, human rights activist Emin Huseynov and the closure of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Further on in the resolution PACE was being asked to call on Azerbaijan to properly investigate the murders of journalists Elmar Huseynov (2005) and Rafiq Tagi (2011).

On 3 Feb, President Aliyev signed an amended media law that restricts press freedom by making it easier to shutter media outlets.

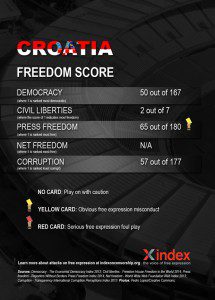

Just today, Reporters Without Borders released its World Press Freedom Index 2015, which places Azerbaijan at 162. That’s down 2 spots from last 2014.

We wish Azerbaijan’s commitment to a “free and diverse media” was more than just words and we will continue to report on these detentions – as we do globally – for as long as these words are not translated into action.

Best regards

Jodie Ginsberg

Chief Executive

Index on Censorship

18 Jun 2014 | Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Middle East and North Africa

GROUP A

GROUP B

GROUP C

GROUP D

GROUP E

GROUP F

GROUP G

GROUP H

This article was published on June 18, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Apr 2014 | Brazil, Digital Freedom, News and features

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

After two years of wrangling, the Brazilian chamber of deputies finally approved the General Internet Framework last week.

The movement that resulted in bill 2126/11 – referred to as Marco Civil da Internet or simply Marco Civil – began in 2007. The Marco Civil was drafted in 2009 by the ministry of justice in partnership with the Center for Technology and Society of the Getulio Vargas Foundation, and with the direct participation of civil society. After extensive public consultation, with over 2,300 contributions, the bill was sent to congress in 2011 and recommended to the president. It outlines the duties and prohibitions on the use of the web, as well as structures the ways in which the courts can request records for user communications and network access.

While the bill has passed the bicameral congress’ lower house, it now needs to be approved by the senate, which will vote this month. If passed, the bill will need presidential approval to become law. It is widely expected that the bill will clear both these hurdles. The process is made all the more urgent as Brazil is set to host Net Mundial – a global forum exploring the future of internet governance — at the end of the month.

Marco Civil was drafted with three key issues in mind: Net neutrality, user privacy and freedom of expression. Under the bill, internet service providers are barred from interfering with connection speeds or content. Civil society strongly backed the framework around net neutrality.

Altogether, five amendments were made to the final text. The main change was the removal of a section of Article 12 whereby the presidency could require, by decree, connection providers to “install or use structures for storage, management and dissemination of data (data centers) in national dominion”, taking its billing into account.

This point was included last year at the request of the government after president Dilma Rousseff voiced complaints about spying by the National Security Agency (NSA). The revised Article 12 provides that Brazilian law will take effect on all companies providing services in the country, including foreign ones.

Another important change was made in the first subparagraph of Article 9, which deals with exceptions to net neutrality, such as discrimination or degradation of services or performance. Such cases were to be resolved by presidential decree. The revised amendment states that cases of exception will follow determinations from the constitution and guidelines of the Agência Nacional de Telecomunicações (telecommunications national agency – Anatel) and the Comitê Gestor da Internet (internet managing committee – CGI).

While the current wording of the bill shows social and political maturity, and seeks to put Brazil on another level in terms of freedoms of expression, it has its blind spots. These includes the storage of user data by ISPs for one year for investigation purposes, which is damaging to privacy. The text can still be changed.

Historic session

The historic vote was watched by a huge television audience, as the sessions of the Chamber of Deputies featuring 400 congressional representatives argued over the bill was broadcast live. Social media lit up, with #MarcoCivil trending on Twitter.

The question is whether in addition to being a massive victory for the government the piece will not end up being used for electioneering in the 2014 elections.

On Twitter, Rousseff said that “the Civil Landmark is a tool of free expression, privacy of the individual and respect for human rights”. She also said that “the approval of the Internet Civil Landmark by the Chamber of Deputies is a victory for all of Brazilian society”. She added that “the project shows the pioneering role of Brazil in a moment that the world debates the security, the privacy and the plurality in the network”.

Representatives said the text was a “parameter to the world”, “a reference in terms of freedom of expression” and “the most democratic process of voting on a bill in Brazil”. British physicist and creator of the web Tim Berners-Lee was quoted in plenary requesting the approval of the Marco Civil. The Brazilian press, which had criticised the original text, only reported the approval of the bill, and published some praise.

Despite the hoopla, Brazilian society remians divided over it. Most people have no idea about what the bill is intended to do. While there are some who support the regulation, others say that Marco Civil is a form of government control of the internet. Others still, just shrug.

A political drama

The approval of the Marco Civil was not an easy vote, as it may have seemed at first glance. The political will for the project to be brought up for a vote was stitched together through political and personal effort by Rousseff. Bill 2126/11, authored by the executive branch, served as political leverage for the PMDB, part of the governing coalition, and threatened to derail the project.

At the height of the crisis, PMDB came close to a break as a government ally, which would have drawn support away from the president. The so-called “block of disgruntled” was dissatisfied with Rousseff’s ministerial reshuffle in early March and required appointments in important ministries. The party also threatened to boycott Marco Civil by voting en masse against the proposal − which would mean fiasco. The tension between the PMDB and Rousseff also came close to derailing coalition alliances ahead of this year’s elections.

Rousseff did not relent even and made a joke about the situation. In Chile, where she participated in the inauguration ceremony of president Michelle Bachelet, she said: “PMDB only gives me joy”, when asked about whether her weight loss had to do with her concern about the crisis in the governing coalition. The statement did not sit well with PMDB, but pleased the vice-president Michel Temer, a member of the party: “It really only gives joy to the government, supporting and helping the government.” The message was explicit: As a Brazilian saying goes, “one hand washes the other and both wash the face”.

After several closed-door meetings tempers were soothed paving the way for the support and the approval of the Marco Civil project. The terms negotiated between the parties are not yet known. What is certain is that the deal has the power to soften a partisan war.

Until last week, Marco Civil had frozen the Chamber of Deputies’ agenda since 2013. The text approved on the night of 25 March was substitutive, with several changes from the last version that was submitted in February. These deleted changes caused controversy, especially because they were seen to serve business interests.

The content of the final version, filled with handwritten addendums, was a draft during the vote. The deputies voted blindly, having no access to the final text and relying on word of the rapporteur, Congressman Alessandro Molon (PT, Workers Party). They voted based solely on the version being manipulated live, with last minute modifications. They voted thanks to agreements in the audience and the theatre of the plenary, and more on the political line than on the legal framework that Marco Civil represented. This is why they voted as a majority. One deputy commented: “This is not the House of knowledge, but of convincing.”

Espionage

In an exclusive report broadcast by the TV show “Fantástico” on TV Globo Network, on the evening of 1 September, it was reported that the Brazilian government and Petrobras had been targeted by the NSA spying. The information was based on documents revealed by whistleblower Edward Snowden to Glenn Greenwald and Globo Network’s journalist Sonia Bridi. According to the report, Rousseff, her advisors and diplomats were also being monitored. All of these revelations visibly irritated the president − who had previously sent the draft of Marco Civil to Congress – and she demanded urgency in putting the bill on the agenda.

In late September, speaking at the opening of the 68th General Assembly of the United Nations in New York, Rousseff advocated the establishment of a multilateral framework for international civil governance and of internet usage. She argued that the actions of United States’ espionage in Brazil had wounded international laws and defied the principles that govern the relationship between the countries.

This article was posted on 2 April, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org