Global heroes battling censorship announced in Index Freedom of Expression Awards shortlist

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

Judges include actor Noma Dumezweni; former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown

- Sixteen courageous individuals and organisations who fight for freedom of expression in every part of the world

A Zimbabwean pastor who was arrested by authorities last week for his #ThisFlag campaign, an Iranian Kurdish journalist covering his life as an interned Australian asylum seeker, one of China’s most notorious political cartoonists, and an imprisoned Russian human rights activist are among those shortlisted for the 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards.

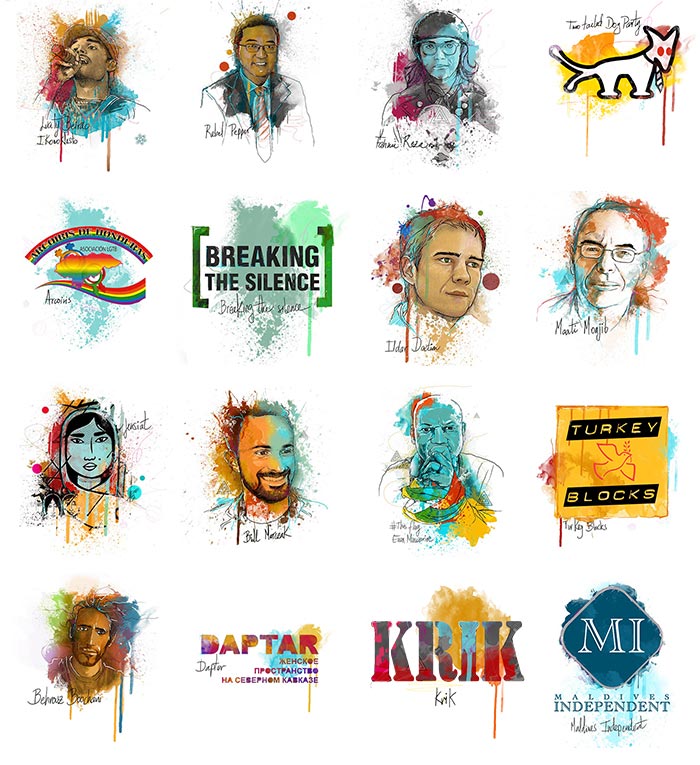

Drawn from more than 400 crowdsourced nominations, the shortlist celebrates artists, writers, journalists and campaigners overcoming censorship and fighting for freedom of expression against immense obstacles. Many of the 16 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution or exile.

“The creativity and bravery of the shortlist nominees in challenging restrictions on freedom of expression reminds us that a small act — from a picture to a poem — can have a big impact. Our nominees have faced severe penalties for standing up for their beliefs. These awards recognise their courage and commitment to free speech,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of campaigning nonprofit Index on Censorship.

Awards are offered in four categories: arts, campaigning, digital activism and journalism.

Nominees include Pastor Evan Mawarire whose frustration with Zimbabwe’s government led him to the #ThisFlag campaign; Behrouz Boochani, an Iranian Kurdish journalist who documents the life of indefinitely-interned Australian asylum seekers in Papua New Guinea; China’s Wang Liming, better known as Rebel Pepper, a political cartoonist who lampoons the country’s leaders; Ildar Dadin, an imprisoned Russian opposition activist, who became the first person convicted under the country’s public assembly law; Daptar, a Dagestani initiative tackling women’s issues like female genital mutilation that are rarely discussed publicly in the country; and Serbia’s Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK), which was founded by a group of journalists to combat pervasive corruption and organised crime.

Other nominees include Hungary’s Two-tail Dog Party, a group of satirists who parody the country’s political discourse; Honduran LGBT rights organisation Arcoiris, which has had six activists murdered in the past year for providing support to the LGBT community and lobbying the country’s government; Luaty Beirão, a rapper from Angola, who uses his music to unmask the country’s political corruption; and Maldives Independent, a website involved in revealing endemic corruption at the highest levels in the country despite repeated intimidation.

Judges for this year’s awards, now in its 17th year, are Harry Potter actor Noma Dumezweni, Hillsborough lawyer Caiolfhionn Gallagher, former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown, designer Anab Jain and music producer Stephen Budd.

Dumezweni, who plays Hermione in the stage play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, was shortlisted earlier this year for an Evening Standard Theatre Award for Best Actress. Speaking about the importance of the Index Awards she said: “Freedom of expression is essential to help challenge our perception of the world”.

Winners, who will be announced at a gala ceremony in London on 19 April, become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given support for their work, including training in areas such as advocacy and communications.

“The GreatFire team works anonymously and independently but after we were awarded a fellowship from Index it felt like we had real world colleagues. Index helped us make improvements to our overall operations, consulted with us on strategy and were always there for us, through the good times and the pain,” Charlie Smith of GreatFire, 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards Digital Activism Fellow.

This year, the Freedom of Expression Awards are being supported by sponsors including SAGE Publishing, Google, Vodafone, media partner CNN, VICE News, Doughty Street Chambers, Psiphon and Gorkana. Illustrations of the nominees were created by Sebastián Bravo Guerrero.

Notes for editors:

- Index on Censorship is a UK-based non-profit organisation that publishes work by censored writers and artists and campaigns against censorship worldwide.

- More detail about each of the nominees is included below.

- The winners will be announced at a ceremony at The Unicorn Theatre, London, on 19 April.

For more information, or to arrange interviews with any of those shortlisted, please contact: Sean Gallagher on 0207 963 7262 or [email protected]. More biographical information and illustrations of the nominees are available at indexoncensorship.org/indexawards2017.

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards nominees 2017

Arts

Luaty Beirão, Angola

Rapper Luaty Beirão, also known as Ikonoklasta, has been instrumental in showing the world the hidden face of Angolan President José Eduardo dos Santos’s rule. For his activism Beirão has been beaten up, had drugs planted on him and, in June 2015, was arrested alongside 14 other people planning to attend a meeting to discuss a book on non-violent resistance. Since being released in 2016, Beirão has been undeterred attempting to stage concerts that the authorities have refused to license and publishing a book about his captivity entitled “I Was Freer Then”, claiming “I would rather be in jail than in a state of fake freedom where I have to self-censor”.

Rebel Pepper, China

Wang Liming, better known under the pseudonym Rebel Pepper, is one of China’s most notorious political cartoonists. For satirising Chinese Premier Xi Jinping and lampooning the ruling Communist Party, Rebel Pepper has been repeatedly persecuted. In 2014, he was forced to remain in Japan, where he was on holiday, after serious threats against him were posted on government-sanctioned forums. The Chinese state has since disconnected him from his fan base by repeatedly deleting his social media accounts, he alleges his conversations with friends and family are under state surveillance, and self-imposed exile has made him isolated, bringing significant financial struggles. Nonetheless, Rebel Pepper keeps drawing, ferociously criticising the Chinese regime.

Fahmi Reza, Malaysia

On 30 January 2016, Malaysian graphic designer Fahmi Reza posted an image online of Prime Minister Najib Razak in evil clown make-up. From T-shirts to protest placards, and graffiti on streets to a sizeable public sticker campaign, the image and its accompanying anti-sedition law slogan #KitaSemuaPenghasut (“we are all seditious”) rapidly evolved into a powerful symbol of resistance against a government seen as increasingly corrupt and authoritarian. Despite the authorities’ attempts to silence Reza, who was banned from travel and has since been detained and charged on two separate counts under Malaysia’s Communications and Multimedia Act, he has refused to back down.

Two-tailed Dog Party, Hungary

A group of satirists and pranksters who parody political discourse in Hungary with artistic stunts and creative campaigns, the Two-tailed Dog Party have become a vital alternative voice following the rise of the national conservative government led by Viktor Orban. When Orban introduced a national consultation on immigration and terrorism in 2015, and plastered cities with anti-immigrant billboards, the party launched their own mock questionnaires and a popular satirical billboard campaign denouncing the government’s fear-mongering tactics. Relentlessly attempting to reinvigorate public debate and draw attention to under-covered or taboo topics, the party’s efforts include recently painting broken pavement to draw attention to a lack of public funding.

Campaigning

Arcoiris, Honduras

Arcoiris, Honduras

Established in 2003, LGBT organisation Arcoiris, meaning ‘rainbow’, works on all levels of Honduran society to advance LGBT rights. Honduras has seen an explosion in levels of homophobic violence since a military coup in 2009. Working against this tide, Arcoiris provide support to LGBT victims of violence, run awareness initiatives, promote HIV prevention programmes and directly lobby the Honduran government and police force. From public marches to alternative awards ceremonies, their tactics are diverse and often inventive. Between June 2015 and March 2016, six members of Arcoiris were killed for this work. Many others have faced intimidation, harassment and physical attacks. Some have had to leave the country because of threats they were receiving.

Breaking the Silence, Israel

Breaking the Silence, an Israeli organisation consisting of ex-Israeli military conscripts, aims to collect and share testimonies about the realities of military operations in the Occupied Territories. Since 2004, the group has collected over 1,000 (mainly anonymous) statements from Israelis who have served their military duty in the West Bank and Gaza. For publishing these frank accounts the organisation has repeatedly come under fire from the Israeli government. In 2016 the pressure on the organisation became particularly pointed and personal, with state-sponsored legal challenges, denunciations from the Israeli cabinet, physical attacks on staff members and damages to property. Led by Israeli politicians including the prime minister, and defence minister, there have been persistent attempts to force the organisation to identify a soldier whose anonymous testimony was part of a publication raising suspicions of war crimes in Gaza. Losing the case would set a precedent that would make it almost impossible for Breaking the Silence to operate in the future. The government has also recently enacted a law that would bar the organisation’s widely acclaimed high school education programme.

Ildar Dadin, Russia

A long-term opposition and LGBT rights activist, Ildar Dadin was the first, and remains the only, person to be convicted under Russia’s 2014 public assembly law that prohibits the “repeated violation of the order of organising or holding meetings, rallies, demonstrations, marches or picketing”. Attempting to circumvent this restrictive law, Dadin held a series of one-man pickets against human rights abuses – an enterprise for which he was arrested and sentenced to three years imprisonment in 2015. In November 2016, website Meduza published a letter smuggled to his wife in which Dadin wrote that he was being tortured and abuse was endemic in Russian jails. The letter, a brave move for a serving prisoner, had wide resonance, prompting a reaction from the government and an investigation. Against his will, Dadin was transferred and disappeared within the Russian prison system until a wave of public protest led to his location being revealed in January 2017. Dadin was released on February 26 after a supreme court order.

Maati Monjib, Morocco

A well-known academic who teaches African studies and political history at the University of Rabat since returning from exile, Maati Monjib co-founded Freedom Now, a coalition of Moroccan human rights defenders who seek to promote the rights of Moroccan activists and journalists in a country ranked 131 out of 180 on the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. His work campaigning for press freedom – including teaching investigative journalism workshops and using of a smartphone app called Story Maker designed to support citizen journalism – has made him a target for the authorities who insist that this work is the exclusive domain of state police. For his persistent efforts, Monjib is currently on trial for “undermining state security” and “receiving foreign funds.”

Digital Activism

Jensiat, Iran

Jensiat, Iran

Despite growing public knowledge of global digital surveillance capabilities and practices, it has often proved hard to attract mainstream public interest in the issue. This continues to be the case in Iran where even with widespread VPN usage, there is little real awareness of digital security threats. With public sexual health awareness equally low, the three people behind Jensiat, an online graphic novel, saw an an opportunity to marry these challenges. Dealing with issues linked to sexuality and cyber security in a way that any Iranian can easily relate to, the webcomic also offers direct access to verified digital security resources. Launched in March 2016, Jensiat has had around 1.2 million unique readers and was rapidly censored by the Iranian government.

Bill Marczak, United States

A schoolboy resident of Bahrain and PhD candidate in computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, Bill Marczak co-founded Bahrain Watch in 2013. Seeking to promote effective, accountable and transparent governance, Bahrain Watch works by launching investigations and running campaigns in direct response to social media posts coming from activists on the front line. In this context, Marczak’s personal research has proved highly effective, often identifying new surveillance technologies and targeting new types of information controls that governments are employing to exert control online, both in Bahrain and across the region. In 2016 Marczak investigated several government attempts to track dissidents and journalists, notably identifying a previously unknown weakness in iPhones that had global ramifications.

#ThisFlag and Evan Mawarire, Zimbabwe

In May 2016, Baptist pastor Evan Mawarire unwittingly began the most important protest movement in Zimbabwe’s recent history when he posted a video of himself draped in the Zimbabwean flag, expressing his frustration at the state of the nation. A subsequent series of YouTube videos and the hashtag Mawarire used, #ThisFlag, went viral, sparking protests and a boycott called by Mawarire, which he estimates was attended by over eight million people. A scale of public protest previously inconceivable, the impact was so strong that private possession of Zimbabwe’s national flag has since been banned. The pastor temporarily left the country following death threats and was arrested in early February as he returned to his homeland.

Turkey Blocks, Turkey

In a country marked by increasing authoritarianism, a strident crackdown on press and social media as well as numerous human rights violations, Turkish-British technologist Alp Toker brought together a small team to investigate internet restrictions. Using Raspberry Pi technology they built an open source tool able to reliably monitor and report both internet shut downs and power blackouts in real time. Using their tool, Turkey Blocks have since broken news of 14 mass-censorship incidents during several politically significant events in 2016. The tool has proved so successful that it has begun to be implemented elsewhere globally.

Journalism

Behrouz Boochani, Manus Island, Papua New Guinea/Australia (he is an Iranian refugee)

Iranian Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani fled the city of Ilam in Iran in May 2013 after the police raided the Kurdish cultural heritage magazine he had co-founded, arresting 11 of his colleagues. He travelled to Australia by boat, intending to claim asylum, but less than a month after arriving he was forcibly relocated to a “refugee processing centre” in Papua New Guinea that had been newly opened. Imprisoned alongside nearly 1000 men who have been ordered to claim asylum in Papua New Guinea or return home, Boochani has been passionately documenting their life in detention ever since. Publicly advertised by the Australian Government as a refugee deterrent, life in the detention centre is harsh. For the first 2 years, Boochani wrote under a pseudonym. Until 2016 he circumvented a ban on mobile phones by trading personal items including his shoes with local residents. And while outside journalists are barred, Boochani has refused to be silent, writing numerous stories via Whatsapp and even shooting a feature film with his phone.

Daptar, Dagestan, Russia

In a Russian republic marked by a clash between the rule of law, the weight of traditions, and the growing influence of Islamic fundamentalism, Daptar, a website run by journalists Zakir Magomedov and Svetlana Anokhina, writes about issues affecting women, which are little reported on by other local media. Meaning “diary”, Daptar seeks to promote debate and in 2016 they ran a landmark story about female genital mutilation in Dagestan, which broke the silence surrounding that practice and began a regional and national conversation about FGM. The small team of journalists, working alongside a volunteer lawyer and psychologist, also tries to provide help to the women they are in touch with.

KRIK, Serbia

Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK) is a new independent investigative website which was founded by a team of young Serbian journalists intent on exposing organised crime and extortion in their country which is ranked as having widespread corruption by Transparency International. In their first year they have published several high-impact investigations, including forcing Serbia’s prime minister to admit that senior officials had been behind nocturnal demolitions in a Belgrade neighbourhood and revealing meetings between drug barons, the ministry of police and the minister of foreign affairs. KRIK have repeatedly come under attack online and offline for their work –threatened and allegedly under surveillance by state officials, defamed in the pages of local tabloids, and suffering abuse including numerous death threats on social media.

Maldives Independent, Maldives

Website Maldives Independent, which provides news in English, is one of the few remaining independent media outlets in a country that ranks 112 out of 180 countries on the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. In August 2016 the Maldives passed a law criminalising defamation and empowering the state to impose heavy fines and shut down media outlets for “defamatory” content. In September, Maldives Independent’s office was violently attacked and later raided by the police, after the release of an Al Jazeera documentary exposing government corruption that contained interviews with editor Zaheena Rasheed, who had to flee for her safety. Despite the pressure, the outlet continues to hold the government to account.