26 Oct 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Wall Street Journal reporter Ayla Albayrak

Last week, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal was convicted of producing “terrorist propaganda” in Turkey and sentenced to more than two years in prison.

Ayla Albayrak was charged over an August 2015 article in the newspaper, which detailed government efforts to quell unrest among the nation’s Kurdish separatists, “firing tear gas and live rounds in a bid to reassert control of several neighborhoods”.

Albayrak was in New York at the time the ruling was announced and was sentenced in absentia but her conviction forms part of a growing pattern of arrests, detentions, trials and convictions for journalists under national security laws – not just in Turkey, the world’s top jailer of journalists, but globally.

As security – rather than the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms – becomes the number one priority of governments worldwide, broadly-written security laws have been twisted to silence journalists.

It’s seen starkly in the data Index on Censorship records for a project monitoring media freedom in Europe: type the word “terror” into the search box of Mapping Media Freedom and more than 200 cases appear related to journalists targeted for their work under terror laws.

This includes everything from alleged public order offences in Catalonia to the “harming of national interests in Ukraine” to the hundreds of journalists jailed in Turkey following the failed coup.

This abusive phenomenon started small, as in the case of Turkey, with dismissive official rhetoric that was aimed at small segments — like Kurdish journalists — among the country’s press corps, but over time it expanded to extinguish whole newspapers or television networks that espouse critical viewpoints on government policy.

While Turkey has been an especially egregious example of the cynical and political exploitation of terror offenses, the trend toward criminalisation of journalism that makes governments uncomfortable is spreading.

Mónica Terribas, journalist for Catalunya Rádio

In Spain, the Spanish police association filed a lawsuit against Mónica Terribas, a journalist for Catalunya Rádio, accusing her of “favouring actions against public order for calling on citizens in the Catalonia region to report on police movements during the referendum on independence.

The association said information on police movements could help terrorists, drug dealers and other criminals.

Undermining state security is a growing refrain among countries seeking to clamp down on a disobedient media, particularly in countries like Russia. In December 2016, State Duma Deputy Vitaly Milonov urged Russia’s Prosecutor General to investigate independent Latvia-based media outlet Meduza’s on charges of “promoting extremism and terrorism” for an article published the day before.

The piece written by Ilya Azar entitled, When You Return, We Will Kill You, documents Chechens who are leaving continental Europe through Belarussian-Polish border and living in a rail station in Brest, a border city in Belarus. Deputy Milonov said he considers the article a provocation aimed at undermining unity of Russia and praising terrorists.

German journalist Deniz Yucel

In Turkey, reporting deemed critical of the government, the president or their associates is being equated with terrorism as seen in the case of German journalist Deniz Yucel who was detained in February this year.

Yucel, a dual Turkish-German national was working as a correspondent for the German newspaper Die Welt. He was arrested on charges of propaganda in support of a terrorist organization as well as inciting violence to the public and is currently awaiting trial, something that could take up to five years.

Ahmed Abba

Outside of the European region, journalists regularly fall foul of national security laws. In April, journalist Ahmed Abba was sentenced to 10 years behind bars by a military tribunal in Cameroon after being convicted of non-denunciation of terrorism and laundering of the proceeds of terrorist acts. Accompanying the decade-long sentence was a fine of over $90,000 dollars. Abba, a journalist for Radio France International, was detained in July of 2015. He was tortured and held in solitary confinement for three months.

The military court allegedly possessed evidence against Abba, who was barred from speaking with the media during his trial, which they found on his computer. Among the alleged evidence was contact information between Abba and the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram. Abba, who was in the area to report on the Boko Haram conflict, claimed he obtained the information that was discovered on his phone from various social media outlets with the intent of using them for his report.

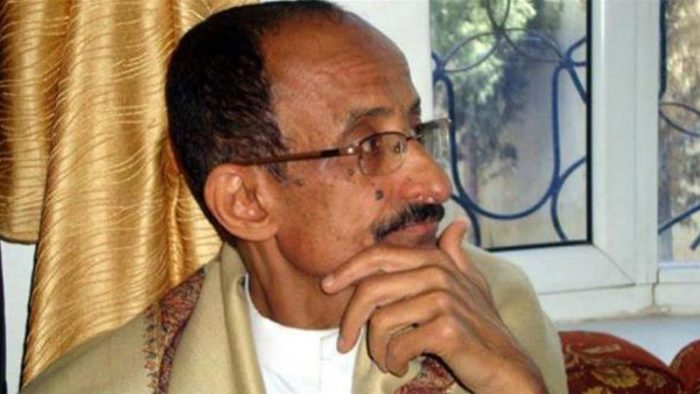

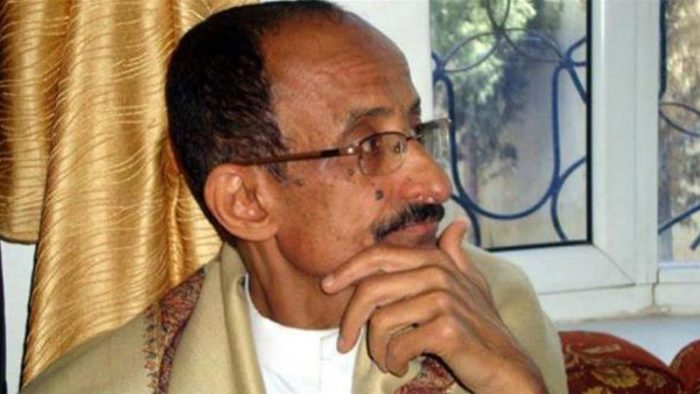

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb al-Jubaihi

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb Al-Jubaihi was sentenced to death earlier this month for allegedly serving as an undercover spy for Saudi Arabian coalition forces. Al-Jubaihi, who has worked as a journalist for various Yemeni and Saudi Arabian newspapers, has been held in a political prison camp ever since he was abducted from his home in September 2016.

Al-Jubaihi is the first journalist to be sentenced to death in Yemen following a trial that many activists believe was politically motivated because of Al-Jubaihi’s columns criticising Houthis.

Journalist Narzullo Akhunjonov

Increasingly, governments are turning to Interpol to target journalists under terror laws. Turkey has filed an application to seek an Interpol arrest warrant for Can Dündar, demanding the journalist’s extradition. In September, Uzbek journalist Narzullo Okhunjonov was detained by authorities in Ukraine following an Interpol red notice.

Uzbek authorities have issued an international arrest warrant on fraud charges against Okhunjonov, who had been living in exile in Turkey since 2013 in order to avoid politically motivated persecution for his reporting.

And governments are also using terror laws to spy on journalists. In 2014, the UK police admitted it used powers under terror legislation to obtain the phone records of Tom Newton Dunn, editor of The Sun newspaper, to investigate the source of a leak in a political scandal. Police powers under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which circumvents another law that requires police to have approval from a judge to get disclosure of journalistic material.

No laughing matter

The Sun editor Tom Newton Dunn

Even jokes can land journalists in trouble under terror laws. Last year, French police searched the office of community Radio Canut in Lyon and seized the recording of a radio programme, after two presenters were accused of “incitement to terrorism”.

Presenters had been talking about the protests by police officers that had recently been taking place in France. One presenter said: “This is a call to people who people who killed themselves or are feeling suicidal and to all kamikazes” and to “blow themselves up in the middle of the crowd”.

One of the presenters was put under judicial supervision and was forbidden to host the radio programme until he appeared in court.

Radio Canut journalist Olivier Combi explained that the comment was ironic: “Obviously, Radio Canut is not calling for the murder of police officers, as it was sometimes said in the press”, he said. “Things have to be put back in context: the words in question are a 30 seconds joke-like exchange between two voluntary radio hosts…Nothing serious, but no media outlet took the trouble to call us, they all used the version of the police.”

Fighting back to protect sources

Two Russian journalists — Oleg Kashin and Alexander Plushev — are pushing back, Meduza reported. Kashin and Plushev filed the lawsuit challenging Russia’s Federal Security Service’s demands that instant messaging apps turn over encryption keys for users’ private communications, which is being driven by Russia’s anti-terror legislation. The court rejected the suit with the judge reportedly found that the government’s demands do not infringe on Plushev’s civil rights.

The journalists had contended that the FSB’s demand violated their right to confidential conversations with sources. Kashin said that in his work as a journalist he had come to rely on apps such as Telegram to conduct interviews with politicians.

Human rights organisation Agora is representing Telegram in a separate case against the FSB, which has fined the app company for failing to comply with its demands.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96229″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/turkish-injustice-scores-journalists-rights-defenders-go-trial/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

About 90 journalists, writers and human rights defenders will appear before courts in the coming days[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96183″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/interpol-the-abuse-red-notices-is-bad-news-for-critical-journalists/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Since August, at least six journalists have been targeted across Europe by international arrest warrants issued by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Jun 2017 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Counter Terrorism, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]New laws to limit and surveil speech on and offline are not the way to tackle extremism. The terrorists who attacked Manchester and London want to undermine our democratic values — our response must not be to curtail those very freedoms.

Yet this is precisely what the heated rhetoric of UK Prime Minister Theresa May and others promises.

Like governments the world over, the UK has suggested that tighter controls over the internet specifically and speech more generally are the way to help prevent such attacks. “We cannot allow this ideology the safe space it needs to breed – yet that is precisely what the internet, and the big companies that provide internet-based services provide,” May said on Sunday in the wake of the London Bridge attack.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”lg” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

We must be extremely wary of the broad brush approaches being hinted at by the government to crack down on extremism on the internet

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]Much focus has fallen on the role of the internet as a venue for recruiting violent extremists, fomenter of propaganda and dark space where terrorists can plan their attacks in secret. It is unsurprising, therefore, in the wake of the recent terror attacks that the UK government has sought to find solutions it believes will make us safer by targeting the internet in particular: politicians thrive on the idea that they should and must do more, that the answers to indiscriminate and horrendous violence lie in new laws, that fresh legislation is always the panacea.

We must be extremely wary of the broad brush approaches being hinted at by the government to crack down on extremism on the internet and we must push back hard against the narrative that says what is needed are more laws — laws that specifically strike at the liberties that are essential for democracy to flourish. Britain already has one of the most advanced systems to detect, prevent and punish terrorism in the world. There is no need for new, indiscriminate laws to punish and surveil speech.

The online “safe spaces” for terrorists to which Theresa May alluded in her speech on Sunday are also the spaces globally that allow activism, information sharing and ordinary political dissent to flourish. Proposed knee-jerk responses — like banning or bypassing encryption — threaten not just the channels used by criminals but those that allow us to conduct secure financial transactions, protect personal data and enable persecuted groups in authoritarian regimes to communicate safely.

If we want to tackle the ideologies that threaten our existence we need to start by protecting democratic values – not diminishing them.

About Index on Censorship

Index on Censorship is a UK-based freedom of expression charity that campaigns against censorship and promotes free expression worldwide. Founded in 1972, Index has published some of the world’s leading writers and artists in its award-winning quarterly magazine, including Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa, Samuel Beckett and Kurt Vonnegut. It also has published some of the greatest campaigning writers from Vaclav Havel to Elif Shafak. Index is part of the Defend Free Speech Campaign, which brings together people from all walks of life, to combat the threat to free speech from the UK government’s extremism disruption orders. Defend Free Speech seeks guarantees for freedom of expression and the right to debate.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1496671071463-fc51cf93-e4eb-3″ taxonomies=”11489″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Dec 2015 | Belarus, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Credit: Shutterstock / Fedor Selivanov

Miklos Haraszti, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Belarus, has called for reforms to the country’s laws and practices that for two decades have stifled freedom of expression.

“Critical opinion and fact-finding are curtailed by the criminalisation of content that is deemed ‘harmful for the State’; by criminal defamation and insult laws that protect public officers and the president, in particular, from public scrutiny; and by ‘extremism’ laws that ban reporting on political or societal conflicts,” Haraszti said in a 6 November statement.

Belarus anti-extremism law came into force in 2007. According to Article 14 of the Law On Countering Extremism, it is prohibited to publish and or disseminate extremist materials, even through the media. Information products propagandising extremist activities can be seized by the decision of state security services, law enforcement agencies, prosecutor’s office or courts. If deemed extremist, the court can order the materials be destroyed.

The threat for free speech lies in the broad definitions of “extremist activities” and “extremist materials”. Under Belarusian law, extremist activities include “degrading of national honor and dignity”. Such provisions are contrary to international standards of freedom of expression.

“Unfortunately, this is one of the indicators of the current legislation of Belarus – the absolute vagueness of definitions and the absolute possibility of law enforcement to interpret them as they want,” Andrey Bastunets, chairperson of Belarusian Association of Journalists, said.

Critical materials regarded as extremist can end up banned. In 2011, the Ministry of Information issued a warning to Autoradio for broadcasting a message “containing calls for extremist activities”. The warning concerned a phrase by Andrei Sannikau, candidate for the presidency in 2010, that “the fate of the country is solved in the square, not in the kitchen”. The Supreme Economic Court and the National Commission on Broadcasting upheld the warning and the radio was stripped of its frequency.

The law has led to frequent seizures of imported printed material and videos by Belarusian customs offices. Usually, the seized materials are examined to determine if the items are extremist, but it is unclear how to properly get any property out of impound. Often the rightful owners are forced to repeatedly ask for the return of their material.

One of the most sensational cases related to “countering extremism” was the recognition of Belarus Press Photo 2011 album as extremist materials in 2013. The album contained images that won in 2011 the National Press Photo contest — an open annual contest of press photography. In November 2012, 41 copies of the album were seized for expert examination at the border with Lithuania border from three photojournalists, who were organisers of the contest.

Then the Belarusian KGB’s Hrodna regional department initiated proceedings to categorise the album as extremist material. Ashmiany District Court decided that the publication under consideration was extremist. The court’s decision was based on the KGB’s report that “the choice of the photos for the photo album in the aggregate reflects only negative sides of the life of the Belarusian people, together with the author’s own insinuations and conclusions, which, with the view of the socially accepted norms and morals, insults the national honor and dignity of citizens of the Republic of Belarus, diminishes the authority of the state power organs, undermines the trust of foreign states, foreign and international organisations to them.”

As a result, the seized copies of the album were ordered to be destroyed. Further, the court decision served as grounds to withdraw the license from Lohvinau, the publisher of the album. At least 17 anti-extremism motivated seizures of publications have been carried out by Belarusian customs officers since then.

In 2014, the National Commission of Experts on Assessment of Information Productions Regarding Extremist Contents was established as a permanent body with regional subcommissions set up in the regions. Two-thirds of the National Commission’s members are state officials — including representatives of the KGB and customs — who often initiate proceedings to recognise a material as extremist. In the first six months of its existence, the National Commission considered over 100 different publications, 25 of which have been recognised as extremist.

In November 2015, Belarusian customs officers seized two publications for expert examination.

On 10 November 2015, Oleksandr Doniy and four other Ukrainian TV journalists were interrogated and searched by Belarusian officers at the Ukraine-Belarus border while traveling by car to Vilnius, Lithuania. The journalists, who were working for the cultural programme Last Barricade, were held for five hours. A total of 22 items were seized, including five copies of a documentary about the Ukrainian Revolution (1917-1921) and 11 books, among them Confession From a Condemned Cell, Marshal Zhukov and Ukrainians During World War II. The Ukrainian journalists have been accused of importing “extremist literature and audio productions”.

On 19 November 2015, a number of human rights books were seized by customs officers from Aliaksandr Hanevich who was returning to Belarus from Lithuania. Those were De-facto Implementation of International Human Rights Standards: The Experience of Belarusian ILIA Program Alumni, Enlightened by Belarusianness by Ales Bialiatski, My Fight by Valery Hrytsuk, The Death Penalty in Belarus and Pervasive Violations of Labor Rights and Forced Labor in Belarus.

Besides the anti-extremism law, the grounds for stifling freedom of speech are contained in the Law On Mass Media. In the beginning of 2015, the new Article 51.1 was incorporated that set the procedure for restricting access to online information resources. It can be carried out extrajudicially by the decision of the ministry of information upon the request of any state body if the online resource disseminates information prohibited by law. The law also prohibits propaganda of extremist activities. Blocking websites can follow only one violation of the law, within three months since it occurred. This concerns access to both Belarusian and foreign websites viewed in Belarus.

In 2015, the ministry of information has restricted access to 40 websites, 11 of them have been blocked for disseminating extremist materials.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

19 Oct 2015 | About Index, Campaigns, Counter Terrorism, mobile, Statements

In its new extremism strategy, the government is proposing measures that will criminalise legitimate speech and shrink the space for open debate throughout society. There is already a wealth of legislation that deals with criminal offences, including the Terrorism Act and the Public Order Act, and there is no need for new laws that will seriously harm everyone’s right to freedom of expression in this country.

“We are concerned that the extremism strategy outlined this morning has the potential to massively damage the reputation of the British educational establishment – universities in particular which should be the home of debate and academic academic inquiry. This will have the effect of ramping up a climate of fear where both lecturers and students are afraid to speak,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO, Index on Censorship.

“The government has created an impossible bind for itself: in the name of protecting our values, it’s now seeking to undermine the most fundamental value of all for democracy – freedom of expression. This is a deeply misguided policy that will not only stigmatise minorities, it will criminalise political speech across society and introduce a culture of caution,” said Jo Glanville, director, English PEN.

The government’s counter-terrorism policy is already having a chilling effect on freedom of expression. Over the past six months, a series of incidents across society indicates that arts and educational institutions are censoring and self-censoring in the mistaken belief that any exploration or discussion of extremism is or may be illegal.

This includes the cancellation of the National Youth Theatre’s production of the play Homegrown, the banning of a Mimsy art work at the Mall Galleries that satirised Isis and the questioning of a school child who discussed ecoterrorism in class.

The space for political speech and artistic expression is rapidly diminishing.