Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Kemel Aydogan’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Turkey. Credit: Mehmet Çakici

Hitler was a Shakespeare fan; Stalin feared Hamlet; Othello broke ground in apartheid-era South Africa; and Brazil’s current political crisis can be reflected by Julius Caesar. Across the world different Shakespearean plays have different significance and power. The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, a Shakespeare special to mark the 400th anniversary of his death, takes a global look at the playwright’s influence, explores how censors have dealt with his works and also how performances have been used to tackle subjects that might otherwise have been off limits. Below some of our writers talk about some of the most controversial performances and their consequences.

(For the more on the rest of the magazine, see full contents and subscription details here.)

Kaya Genç on A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream in Turkey

“When Turkish poet Can Yücel translated A Midsummer’s Night Dream, he saw the potential to reflect Turkey’s authoritarian climate in a way that would pass under the radar of the military intelligence’s hardworking censors. Like lovers in Shakespeare’s comedy who are tricked by fairies into falling in love with characters they actually dislike, his adaptation [which was staged in 1981 and led to the arrests of many of the actors] drew on the idea that Turkey’s people were forced by the state to love the authority figures that oppressed them the most. They were subjugated by the military patriarchy, the same way the play’s female and artisan characters were subjugated by Athenian patriarchy.

Kemal Aydoğan, the director of the latest Turkish adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, described the work as ‘one of the most political plays ever written’. For Aydoğan, the scene in which the Amazonian queen Hippolyta is subjugated and taken hostage by the Theseus marks a turning point in the play. ‘That Hermia is not allowed to marry the man she loves but has to wed the man assigned to her by her father is another sign of women’s subjugation by men,’ he said. This, according to Aydoğan, is sadly familiar terrain for Turkey where women are frequently told by male politicians to know their place, keep silent and do as they are told.’ ”

Claire Rigby on Julius Caesar in Brazil

“In a Brazil seething with political intrigue, in which the impeachment proceedings currently facing President Dilma Rousseff are just the most visible tip of a profound turbulence which has gripped the country since her re-election in October 2014, director Roberto Alvim’s 2015 adaptation of Julius Caesar was inspired by a televised presidential debate he saw in the final days of the election campaign, in which centre-left Rousseff faced off against her centre-right opponent Aécio Neves. ‘I watched the debate as it became utterly polarised between Dilma and Aécio, and the famous clash between Mark Antony and Brutus instantly came to mind,’ he said. ‘It was the idea that the same facts can be drawn in such completely different ways by the power of speech: the power of the word to reframe the facts, and its central importance in the political game.’ ”

György Spiró on Richard III in Hungary

“Richard III was staged in Kaposvár, which had Hungary’s very best theatre at the time. This was 1982.

Charges were brought against the production, because the Earl of Richmond wore dark glasses. A few weeks earlier, on 13 December 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared a state of emergency in Poland. For health reasons he wore sunglasses every time he appeared in public.”

Simon Callow on Hamlet under Stalin and the Nazis

“In 1941, Joseph Stalin banned Hamlet. The historian Arthur Mendel wrote: ‘The very idea of showing on the stage a thoughtful, reflective hero who took nothing on faith, who intently scrutinized the life around him in an effort to discover for himself, without outside ‘prompting,’ the reasons for its defects, separating truth from falsehood, the very idea seemed almost ‘criminal’.’ Having Hamlet suppressed must have been a nasty shock for Russians: at least since the times of novelist and short story writer Ivan Turgenev, the Danish Prince had been identified with the Russian soul. Ten years earlier, Adolf Hitler had claimed the play as quintessentially Aryan, and described Nazi Germany as resembling Elizabethan England, in its youthfulness and vitality (unlike the allegedly decadent and moribund British Empire). In his Germany, Hamlet was reimagined as a proto-German warrior. Only weeks after Hitler took power in 1933 an official party publication appeared titled Shakespeare – A Germanic Writer.”

Natasha Joseph on Othello in South Africa

“In 1987, actress and director Janet Suzman decided to stage Othello in her native South Africa, bringing ‘the moor of Venice’ to life at Johannesburg’s iconic Market Theatre. It was just two years since Prime Minister PW Botha had repealed one of apartheid’s most reviled laws, the Immorality Act, which banned sexual relationships between people of different races. Even without the legislation, many white South Africans baulked at the idea of interracial desire. No wonder, then, that Suzman’s production attracted what she has described as ‘millions of bags full of hate letters from people who thought that this was an outrage’.

But in a country famous for sweeping censorship and restrictions on freedom of movement, speech and association, the play was not banned. Why? Because the apartheid government ‘would have been the laughing stock of the world if they had banned Shakespeare’, Suzman told Index on Censorship. ‘Any government would be really embarrassed to ban Shakespeare. The apartheid government was frightened of ridicule. Everyone is frightened of laughter.’ ”

For more articles on Shakespeare’s battle with power around the world, see our latest magazine. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year, with a free trial). Copies are also available in excellent bookshops including at the BFI, Mag Culture and Serpentine Gallery (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon or a digital magazine on exacteditions.com. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

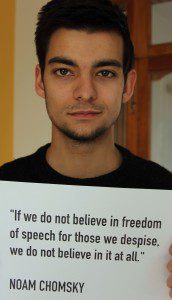

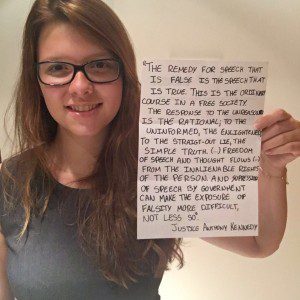

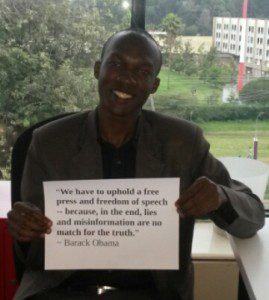

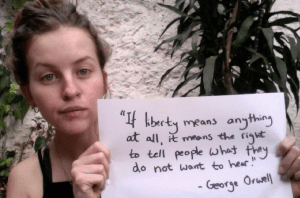

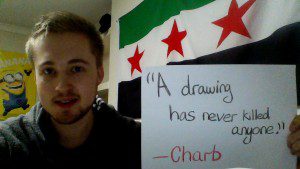

Index on Censorship recently appointed a new youth advisory board who attend monthly online meetings to discuss current freedom of expression issues and complete related tasks. As their first assignments they were asked to provide a short bio to introduce themselves, along with a photograph of them holding a quotation highlighting what free expression means to them.

Simon Engelkes

I am from Berlin, Germany, where I study political science at Free University Berlin. I have worked as an intern with Reporters Without Borders and RTL Television, which made me passionate about the importance of freedom of speech.

I believe that freedom of expression forms an important cornerstone of any effective democracy. Journalists and bloggers must live without fear and without interference from state or economic interests. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Journalists, authors and everyday citizens are imprisoned or killed by radicals, state agencies or drug cartels. Raif Badawi, James Foley, Khadija Ismayilova, Avijit Roy – the list is endless.

We need to remind ourselves and the powerful of today, that freedom of expression as well as freedom of information are basic human rights, which we have to defend at all costs.

Mariana Cunha e Melo

Mariana Cunha e Melo

I am from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. I graduated from law school in Rio and I have a degree from New York University School of Law. My family has taught me about the dangers of censorship and dictatorship, so I have always been interested in studying civil rights. This was the main reason I decided to study law.

I grew up listening to stories about the media censorship in Brazil during the military dictatorship. The fight against the ghost of state censorship has always sounded very natural to me – and, I believe, to all my generation. When I finished law school I found out that the new villain my generation has to face is the censorship based on constitutional values. The argument has changed, but the censorship is not all that different. So I decided to dedicate my academic and my professional life as a lawyer to fight all sorts of institutionalised censorship in Brazil.

Ephraim Kenyanito

Ephraim Kenyanito

I was born and raised in Kenya, and I am currently working as the sub-Saharan Africa policy analyst at Access Now, an international organisation that defends and extends the digital rights of users at risk around the world. My role involves working on the connection between internet policy and human rights in African Union member countries. I am an affiliate at the Internet Policy Observatory (IPO) at the Center for Global Communication Studies, University of Pennsylvania. I also currently serve as a member of the UN Secretary General’s Multi-stakeholder Advisory Group on internet governance.

The reason why I have always been passionate about protecting the open internet is that it is a cornerstone for advancing free speech in the post-millennium era and there is a great need to build common ground around a public interest-oriented approach to internet governance.

Emily Wright

I grew up in Portugal, and I am now based between London and Bogotá, Colombia. I am a freelance filmmaker and journalist. Working in documentary production and community-based, participatory journalism informed a growing interest in journalistic practices, freedom of expression and access to information.

I believe that one of the greatest threats to freedom of expression is the flagrant violation of civil liberties under the banner of national security. The war on terror, underscored by Bush’s declaration “You’re either for us or against us”, has collapsed the middle ground, suppressing any struggles that challenge that statement. Freedom of expression has become a pretext for silencing those who have the least access to it; those who do not fall in line with the global order’s supposed defence of freedom against barbarism and obscurantism.

Mark Crawford

Mark Crawford

I’m originally from Birmingham, and now a postgraduate student at University College London, specialising in Russian and post-Soviet politics. This has inevitably educated me on the pressures exerted upon freedom of expression in Russia, whose suffocated and disenfranchised opposition journalists I am currently investigating.

Hostility to free expression has become a staple of my university life. Rather than developing a coherent set of ideologies to challenge toxic values in the open, it has become mainstream for students of the most privileged universities in the world to veto them on behalf of everyone else, no-platforming and deriding free speech.

I am convinced that there is no point fighting for an egalitarian society if any monopolies over truth are permitted. Freedom of speech is, therefore, something I am keen to promote in whatever small way I can.

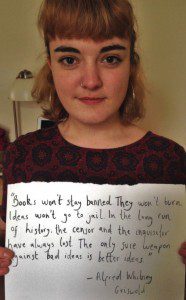

Madeleine Stone

My home is in south-east London but I spend most of my time in York, studying for my bachelor’s degree in English and related literature. I am currently the co-chair of York PEN, the University of York’s branch of English PEN, and a founding member of the Antione Collective, a human rights-focused theatre company.

Studying literature from across the globe has introduced me to issues of freedom and censorship, and the devastating effects censorship can have on national progress. Freedom of expression on campuses is hugely important to me as a student and it is currently under threat. Well-meaning individuals are shutting down the open debate that is vital to academic institutions. The only way to fight harmful ideas is to engage them head-on and destroy them through academic debate, not to ban them.

Layli Foroudi

I am a journalist and student currently studying for a MPhil in race, ethnicity and conflict at Trinity College Dublin. It was studying literary works from the Soviet period during my undergraduate degree in Russian and French at University College London that initially highlighted the issue of censorship for me. The quote I selected, “manuscripts don’t burn”, is from the book Master and Margarita by Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. He wrote about the hardship that many writers faced as they had to adjust their own writing in accordance with the authority, as well as the fact that not all that is written can be taken to be true.

I think that these themes are very relevant today. Whether people are censored or self-censor out of fear of punishment or of being wrong, limiting freedom of expression results in loss of debate, of exchange and of creativity. Being denied freedom of expression is being denied the right to participation in society.

Ian Morse

Ian Morse

I have been involved in journalism since I began studying at Lafayette College, Pennsylvania, USA, and have been engaged in press freedom and reporting in three countries since then. I studied in Turkey last spring, where I interviewed and wrote about journalists and press freedom. It motivated me to begin researching and writing on my own about these topics. Now, as I study for a semester in Cambridge in the UK, I continue to talk about and advocate for free speech and press.

I find it absolutely amazing the power words and information can have in a society. It becomes then extremely damaging to realise that some things cannot be published because they conflict with those in power. Free speech is now becoming a hot topic around the world, particularly among youth, and it makes it all the more important to be able to approach freedom of expression critically and objectively.

Contra Band is a new commission, by Leah Lovett, which brings together musicians and audiences from Brazil and the UK for an experimental live performance of songs censored in both countries between 1964-1985. These dates mark the duration of the military dictatorship in Brazil

Contra Band Tours – Saturday 26th July (6-7pm & 8-9pm)

Audiences are invited on a floating journey, whilst we connect to a live link up with CASA 24, an artist led venue based in Rio De Janeiro. Musicians in both venues will attempt to learn, play and understand their counter parts censored songs.

Contra Band Talk – 3.30-4.30pm

Artist Leah Lovett will be joined by Julia Farrington and Melody Patry from Index on Censorship for a discussion examining issues of cultural censorship within Brazil, explored in Lovett’s new live performance Contra Band for The Floating Cinema. The talk will take place at Kings Place.

Lovett draws on her experience of collaborating with musicians both in London and Rio de Janeiro, and will share her research into cultural creative strategies which respond to political instability and creative invisibility during the Brazilian military regime. Index on Censorship will examine the current challenges facing online freedom of expression, exploring the country’s growing profile in global internet governance debates and the potential consequence of its domestic internet policies.

Index on Censorship is an international organisation that defends and promotes the rights to freedom of expression. The inspiration of poet Stephen Spender, Index was founded in 1972 to publish the untold stories of dissidents behind the Iron Curtain. Today this organisation fights for free speech, challenging censorship globally whenever and wherever it occurs.

Leah Lovett is an artist and writer currently researching a PhD at the Slade, UCL, with support from the AHRC. Her project investigates the spatial politics of Brazilian theatre director Augusto Boal’s invisible theatre as a means of opening up questions and possibilities for her own performance-based practice.

BOOKING DETAILS

Talk: BOOK HERE Free (booking essential) – 15.30 – 16.30 (taking place at Kings Place)

Tour Tickets: BOOK HERE £5.00; £3.00 conc. – timings 18.00 or 20.00 (on-board The Floating Cinema)

Journalist and author Luiz Reffato (Photo: Companhia das Letras)

While researching Brazil’s legislation called the biographies’ law, Index on Censorship’s Brazil contibutor Simone Marques spoke to award-winning Brazilian author Luiz Ruffato, whose works include acclaimed novel They Were Many Horses.

Index: By defending the idea of controlling of literary works, such as biographies, wouldn’t some Brazilian artists be executing the role of a censor?

Ruffato: This is a paradoxical subject, because these artists live from the public image they built. People do not buy only a song or a film, people also buy the exposition of this artist. And the moment he becomes a public figure he is no longer a private figure. If this person is no longer a private figure, it is possible that he may have his own life scrutinised. I do not see any problem with that. I think anyone can manage their own life the way they feel like. Whoever wants to write a biography about me can keep calm. They will find absolutely nothing that may dishonour my image. But if they did find something, it would be okay, because I am exposing myself, I am living off that, I am somehow using my public image to make money. Therefore I think that when you move into this public world, you must be aware of that.

I believe it is everyone’s right to know who the people that make the history of their country are, and the artists also make the history of a country — with or without a political standpoint, he is contributing or not contributing to thinking about the country. Therefore I believe it is perfectly reasonable that you know who this person is. That is why I am a little bit shocked, because we must defend freedom under any circumstance; and it is not relative freedom, freedom for me is a universal concept.The freedom we have here appears more like a relative freedom.

We are living a very strange period in Brazil, a moment when the issue of intolerance is really present. This is very curious because we had a military dictatorship, we have a political history of intolerance. And it shocks me that in the exact moment when we are exercising the biggest continued period of democracy, we are at the same time living a moment of absolute intolerance. It is not just a matter of biographies. Politically, any criticism of your actions immediately positions you within a certain ideological bias. It is a binary judgment; it is yes or no. Moreover, life is not yes or no, life is often made up of maybes, and that is why I am shocked because this positioning of intolerance does not take us to a good place.

Index: Where do you notice this type of intolerance?

Ruffato: This intolerance occurs at all levels. For example, in the virtual world. It is the place of intolerant practices, because there people exercise their prejudices and their authoritarian world views, I am shocked, it is absurd.

This positioning against the biographies I think is a bias of intolerance, an authoritarian bias. It is as if you are being placed in specific niches all the time, and I refuse to do that. I try to exercise the freedom that fits me by never having truths — not imposing truths. I defend relative truths. As well as believing that freedom is absolute, I believe truth must be relative. There is only absolute freedom where truths are relative. Where there is absolute truth there is no freedom.

In Brazil, we have a very childish thing, something that children also have , that is of closing our eyes and pretending things have disappeared. I think we have this in our society, you know? It is as if we closed our eyes and that problem did not exist anymore. We have never stopped to discuss our political history, which is a history of dictatorships. For example, the end of the Brazilian dictatorship did not happen because there was a revolution: it was an agreement between the politicians and the military that included a wide amnesty, general and unrestricted. In other words, nobody killed nobody, nobody did anything to anyone, let us play forward. Obviously, this deeply marks our society. We are an extremely authoritarian and intolerant society.

We are xenophobic, we are racists, we are sexists, we are homophobic, and this shines well on the internet. And we are hypocrites as well. We are not a bit cordial. We kill: domestic violence in Brazil is among the highest in the world, and this happens inside our homes; urban violence in Brazil is among the highest in the world. No, we are not a bit cordial. We are only cordial when people agree with us. When somebody disagrees with us, our reaction is extremely violent. But the Brazilian does not disagree in front of the person. We are used to give a pat on the back and, when the person leaves, we stick the knife in their back. Nobody admits that they do it. People do things, or do not do things, and do not have the guts to tell you. We do not have the culture of divergence, of debate. When we diverge, we always react in a hidden way, because disagreement is something unacceptable, it is terrible.

Index: If the biographies’s law is approved in the senate, we will have, really, more freedom to publish books about people?

Ruffato: This is another problem. I think that where there is an excess of laws, they are meant to be circumvented. The less laws there are, the better, because then you know where you are going. Brazil is a country of lawyers, so you must make many laws so they contradict each other and have loopholes. Particularly, I assume that the biographer is a decent person, that he is an intellectually honest person. Therefore, when an author writes a biography, he will face the biographee as a fallible and susceptible to making wrong decisions human being. The author should have a very well grounded and contextualized story he is telling. If the author is not an honest, decent person, and if the biographee’s family feel somehow offended by the work, then I think it is absolutely correct that they bring an appeal or a lawsuit to force the author to confirm, correct or retract what was written. This is within the norm. We have to protect the biographee, this is indisputable. I think we have to have a legislation that protects the biographee, but that protects him from libel, slander and infamy, not from writing things that were factual and occurred. Because otherwise we will fall into a very curious situation. For example, an author who wants to tell the life story of a president would have to have the subject or his family authorise the biography: what kind of history will we tell? It is a government biography.

So, how will we tell the history of Brazil? A history where the ills of Brazil cannot be told? A history, for example, where there is no extermination of indigenous. So we run a very serious risk of failing to tell a more decent history, with its contradictions, because history is also not a truth, but it is a narrative, and biographies also help to compose these narratives. I think this is very dangerous.

Our laws are made to be circumvented and are not clear. I think that this [biographies’ law] should not be an issue. They exist, people live, and some people have importance beyond a moment. So, I think that that should not even be a matter of discussion. But as it is, I do not keep calm, things can end up taking an unexpected turn into intolerance. There will always be gaps because the laws are not clear. And it’s a huge pretension for someone to want to take care of their image as if it was something personal, of their own. It is so stupid! You may describe your father, and each sibling will tell the story a different way, no one will even have the same father or mother. It is a silly idea to think that someone can have an authorised biography because that biography tells “the truth”. I am very afraid of societies that have truths. I do not trust them, because a society that has absolute truths must be very sick, there is something very wrong with it.

Index: Have you ever faced any kind of censorship in Brazil?

Ruffato: The book Eles Eram Muitos Cavalos (2001) was adopted in a university of Minas Gerais admission test and later on was “unadopted”. Because the admissions test was of a religious institution, they claimed that there was too much bad language in the book. Yes, the book has some profanity, but they are in a context. There is no curse word just for the sake of being a curse word. It was the only episode about it. And if there was some problem of constraint in a work of mine, I would keep writing anyway. I write for my readers, not to please anyone.

Index: If you could write a biography today, within this context of censorship? Who would?

Ruffato: I would like to do a biography, yes, but of a person who probably will not cause any problems, someone who has been very biographed, which is Machado de Assis. Just to change the focus, there are already many biographies of him. My theory is that he would not have written what he wrote had he not been who he was. He was a person who had a look from the bottom up. It was this gaze that I think determines the type of literature that he wrote. But I’m very interested in writing a fake biography. When you tell someone else’s story, you are telling your own story, as psychoanalysis says. I want to radicalize it, though, creating a character whose biography I would write. It is not a novel. It is a fake biography, in which I would tell the story of the character with many witnesses, with hundreds of interviews, many documents read, but it was all fake. Maybe I get to be sued: it would be an authorized biography “unauthorized”.

This article was published on July 17, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org