25 Nov 2015 | Asia and Pacific, Malaysia, mobile, News and features

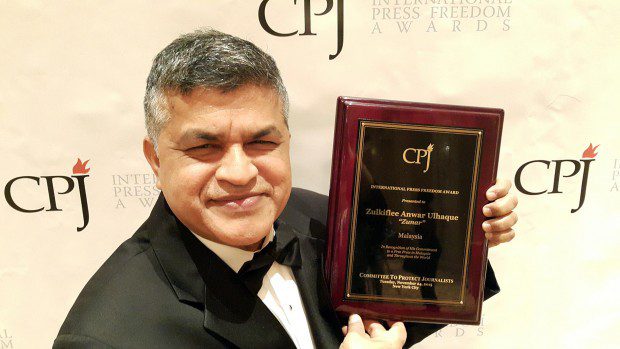

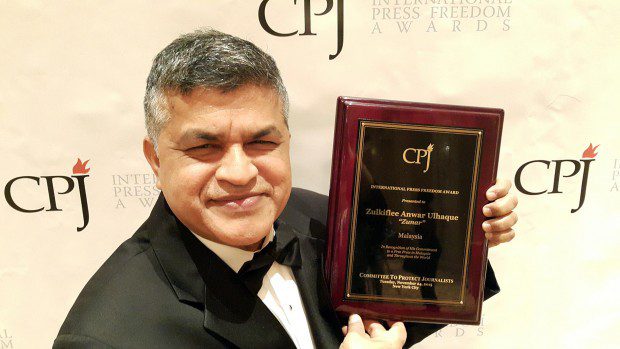

Zunar with his International Press Freedom Award

Malaysian cartoonist Zunar has won the International Press Freedom Award 2015 from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

The political cartoonist, who uses his work to expose abuses of power and corruption in Malaysia, was presented the award yesterday evening at a gala dinner at The Waldorf Astoria, New York.

In his acceptance speech, Zunar dedicated the award to “the Malaysians who have equally pushed for reform”. He also took the opportunity to criticise the Malaysian government: “It is both my responsibility and my right as a citizen to expose corruption, wrong-doing and injustices. Laws like the Sedition Act mean that drawing cartoons is a crime.”

“The government of Malaysia is a cartoon government; a government of the cartoon, by the cartoon, for the cartoon — sorry Abraham Lincoln,” Zunar joked. “For asking people to laugh at the government, I was handcuffed, detained, thrown into the lock-up. But I kept laughing and encouraging people to laugh with me. Why? Because laughter is the best form of protest.”

Zunar currently faces 43 years in prison on nine separate charges of sedition for tweets he wrote criticising Malaysia’s judiciary over the incarceration of a Malaysian opposition leader. His court case was due to begin on 6 November. However, the cartoonist and his lawyers applied to have the case referred to the High Court, delaying proceedings. The application is set for a hearing on 8 December.

The threat of imprisonment obviously hasn’t deterred him from continuing with his work. “My mission is to fight through cartoons,” Zunar said. “Why pinch when you can punch? People need to know the truth and I will continue to fight through my cartoons. I want to give a clear message to the aggressors — they can ban my cartoons, they can ban my books, but they cannot ban my mind.”

Four of Zunar’s most celebrated cartoons are on display at London’s Cartoon Museum until January.

This article was posted on 25 November 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Apr 2014 | Africa, News and features, Swaziland

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

The case against human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor of the independent Nation magazine, Bheki Makhubu, resumes today in Swaziland after adjourning over Easter. The two were arrested last month, and face charges of “scandalising the judiciary” and “contempt of court”. The charges are based on two separate articles, written by Maseko and Makhubu and published in the Nation, which strongly criticised Chief Justice Michael Ramodibedi, levels of corruption and the lack of impartiality in the judicial system in Swaziland.

Makhubu’s home was raided by armed police, and the men were initially denied the right to a fair trial when their case was heard privately in the judge’s chambers. They were also denied bail as they were deemed to pose a security risk. Over the last few weeks, they have been released, and re-arrested in a highly unconventional course of events, so far spending 26 days in custody.

Last week, armed police blocked the gates of the High Court and stopped members of the public and banned political parties from attending the case. Continuous requests to move the case to a larger courtroom so that journalists, observers and family members could monitor proceedings have been refused. The Judicial Service Commission (JSC) said this was in order to minimise disturbances in the court.

There was public outcry as the two men appeared in court bound by leg irons. This highly unusual treatment has been described as “inhumane and degrading” by the Swaziland Coalition of Concerned Civic Organisations (SCCCO). When questioned on the issue, Mzuthini Ntshangase, Commissioner of His Majesty’s Correctional Services told the media to “stay away from [commenting on] security matters”.

Maseko and Makhubu’s lawyers have claimed that the arrests are a blatant form of judicial harassment intended to intimidate the accused and are unconstitutional, unlawful and irregular. They are currently being held in a detention centre in the capital Mbabane, and journalists have been prevented from visiting.

The local press has faced severe censorship of its reporting on the case. The JSC warned the media and public against commenting on the case. It argues that: “[Freedom of expression] is not as absolute as the progressive organisations and other like-minded persons seem to suggest.” Managing editor of The Observer newspaper, Mbongeni Mbingo commented on the case in his editorial: “For now though, the rest of us will do well to toe the line, and hold our breath and mourn in silence for our beautiful kingdom.” One local journalist said he was scared to comment on the situation for fear of arrest – or worse.

Maseko and Makhubu’s articles highlighted the disturbing case of Bhantshana Gwebu, a civil servant employed to monitor the abuse of government vehicles, who was arrested after stopping a high court judge’s driver for driving without the required documentation. Gwebu was detained for a week without charge and initially denied the right to representation. He now also faces a contempt of court charge.

In his article, Maseko wrote that “fear cripples the Swazi society, for the powerful have become untouchable. Those who hold high public office are above the law. Those who are employed to fight corruption in government are harassed, violated and abused”. He described how the Swazi people have lost faith in the institutions of power, as cases like Gwebu’s show how such institutions are being used to settle personal scores “at the expense of justice and fairness”.

Their case has sparked both local and international condemnation, from civil society organisations and the Swazi business community, as well as EU representatives and the American Embassy. “The only crime in this case is judges abusing the judicial system to settle personal scores,” says CPJ Africa advisory coordinator Mohamed Keita. The Law Society of Swaziland has called the arrests an “assassination of the rule of law”. They claim that the Swazi court had become the persecutor instead of the defender of the rights and freedoms of the people. But many in the country are still scared to speak out. The media operates under strict government imposed regulations. Journalists are often forced to exercise various forms of self-censorship when reporting on sensitive issues.

The arrests and the continuation of an abysmal human rights record could have wider implications for Swazi society and the economy. The situation threatens to further derail Swaziland’s highly beneficial African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) with the United States, which is currently being reviewed in Washington. AGOA requires that a country demonstrates that it is making progress towards the rule of law and protection of human rights — including freedom of expression. “There is peace in Swaziland,” the head of the country’s Federation of Trade Unions, once said, “but it’s not real peace if every time there is dissent, you have to suppress it. It’s like sitting on top of a boiling pot.”

This article was originally posted on 22 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Sep 2013 | Americas, Mexico, News and features

This September marks the anniversary of the murders of four Mexican journalists. Alejandro Zenón Fonseca Estrada, Norberto Miranda Madrid, Luis Carlos Santiago and Maria Elizabeth Macías Castro were each killed within a year of each other, from 2008 to 2011. They were all covering drug cartels and corruption, and not a single person has been brought to justice in these murder cases.

This September marks the anniversary of the murders of four Mexican journalists. Alejandro Zenón Fonseca Estrada, Norberto Miranda Madrid, Luis Carlos Santiago and Maria Elizabeth Macías Castro were each killed within a year of each other, from 2008 to 2011. They were all covering drug cartels and corruption, and not a single person has been brought to justice in these murder cases.

Alejandro Zenón Fonseca Estrada, 33, host of a popular morning call-in show called “El Padrino Fonseca” (The Godfather Fonseca) was gunned down on September 24, 2008, by unidentified men as he was hanging up anti-violence posters.

Norberto Miranda Madrid, 44, was a Web columnist and host for the online station Radio Visión. He was shot multiple times by two masked gunmen in the offices of the radio station on September 23, 2009.

Luis Carlos Santiago worked as a photographer with the local daily El Diario. On September 16, 2010, he was shot and killed by unidentified gunmen. He was 21.

Maria Elizabeth Macías Castro, 39, tweeted about activities of criminal groups and covered the topic on the website Nuevo Laredo en vivo (Nuevo Laredo Live) using the pen name “La NenaDLaredo” (The girl from Laredo). On September 24, 2011, her decapitated body was found with a note that identified the website and her pseudonym.

Speak Justice Now is a campaign against impunity by the Committee to Protect Journalists. We encourage you to join thousands around the world to tweet Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto today demanding an end to impunity using the hashtag #SpeakJusticeNow.

8 Jun 2012 | Americas, Index Index, minipost

A constitutional amendment was given final approval in Mexico yesterday [7 June] making attacks on the press a federal offence in Mexico. The amendment, passed by 16 state legislatures, allows federal authorities to investigate and punish crimes against journalists, persons or installations when the right to information or the right to expression is affected. Press freedom group Committee to Protect Journalists heralded the “landmark legislation”, with the groups’s senior programme coordinator for the Americas, Carlos Lauría, deeming it a “first step to stop impunity in the killings of Mexican journalists.”