12 Oct 2022 | News and features

“If there is ever an opportunity to try and pretend a country is a nice country, it’s when everyone is diverted by someone kicking a football,” said Ruth Smeeth, CEO of Index on Censorship. Smeeth was introducing a panel discussion entitled “Qatar 2022: When Football and Free Speech Collide”. Hosted in collaboration with Liverpool John Moores University, the event marked the launch of the Autumn 2022 edition of the Index on Censorship magazine, which looks at the role of football in extending or crushing rights ahead of the Qatar World Cup.

Index on Censorship Editor-in-Chief Jemimah Steinfeld was joined by David Randles, the BA Sports Journalism programme leader at Liverpool John Moores University, who has spent much of his career on sports desks and in press boxes. She was also joined by Connor Dunn, a public relations account manager who deals with big names from the football world, including Liverpool footballer Trent Alexander-Arnold, and was formerly a journalist at Reach PLC.

The issue of whether the FIFA World Cup 2022 being held in Qatar will be a force of change for good was prominent. Dunn was unsure whether there would be any long-term change in the country but felt there will in the short term, saying that “Qatar will want to show the world they are the best country on earth. They’ll be lax with those sort of rules people in the West will be used to [the human rights violations], as there will be potential for stories to be blown up”.

Therein lies a danger, as Steinfeld pointed out. Reeling off a series of examples, she said: “All of the editorials said that while France won the 2018 World Cup Putin was the real winner. The world forgot about the invasion about Crimea.” The fear therefore is that Qatar will relax their attacks on human rights during the tournament, court international leaders, put on a great show and as a result people will walk away with a much better impression of the country than they really should.

Despite attempts to appear more moderate, Randles said that he thinks most minorities would not visit the country due to safety issues. He said: “Would you go to support your team in a regime which doesn’t support you? I don’t think so. If you don’t feel safe, why would you go?” He also pointed out the fact that in Qatar’s neighbouring country Saudi Arabia (whose Sovereign Fund bought Newcastle FC last year), women still cannot attend football games.

Naturally discussion came round to the issue of migrant workers, who have died in huge numbers during the building of infrastructure for Qatar. Sadly the exact numbers are hard to come by, a nature of how tightly information is controlled in the country.

Dunn though highlighted one potential positive that has emerged from the heightened awareness of awful working conditions in Qatar. With claims of potential slave labour being used due to Qatar’s punitive ‘Kafala’ system (which has since been reformed on the back of World Cup coverage), there are hopes for reparations in the future. Dunn said: “There are calls to give the same amount of money the World Cup winner will win, which is about 440 million dollars, to make reparations and give that to underpaid migrant workers and families of those who have died. It’s not a big chunk of the predicted profits from the tournament but goes some way to changing things.”

On other positives that could come out of Qatar, all the panel agreed that football still has a unique way to be transformative. Steinfeld cited Permi Jhooti’s story from the new magazine which inspired the film Bend it Like Beckham, an interview with the head of the Afghan Women’s football team and the England Lionesses winning the recent European Championships for the nation’s first major trophy in 56 years.

And of course footballers, with their millions of fans, are often more listened to than politicians and could use their platform when in the country to raise rights issues. While they accepted that footballers shouldn’t be compelled to speak up, the event was full of examples of those who have – like Marcus Rushford and his campaign for free school meals – and in so doing have brought about important and far-reaching societal change.

9 Nov 2020 | Africa, News and features, Nigeria

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Recent protest in Nigeria. Credit: TobiJamesCandids/WikiCommons

A few weeks ago, Nigeria looked to be at breaking point. President Muhammadu Buhari had called in the army to quash large-scale protests that had filled the country’s streets.

Rather than allow peaceful protests, the army were responsible for a number of state killings as they fired upon their compatriots. For example, on 20th October, in the city of Lekki, around 12 people were killed, according to human rights group Amnesty International. This and other examples of violence shown on social media provoked real anger.

While the protests have died down, the desire for change has not gone away. With their right to free speech violently infringed upon by their own army, Nigerians are looking for alternative ways of protesting.

Poet and journalist Wana Udobang shed light on how the movement has adapted and on the feeling in the country.

“I think that hope was so high that by the time the 20th happened, and the army opened fire, we all encouraged people to stay home,” she said. “We all wanted change but nobody wanted people to die.”

“We have moved into the stage of [looking at] what we do strategically. If you go on social media, a lot of the talk is about getting young people into leadership and where they can make and impact change. There is an active movement for a more sustainable change. In a way, the protests were a first step in demanding for accountability and change. For a long time we were just voting between the devil and the deep blue sea.”

The protests originally began against the Nigerian police unit known as the “special anti-robbery squad”, or “SARS”, but have since become more of a protest aimed against police brutality and wider law enforcement. SARS was actually disbanded on 11 October, but demonstrations continued thereafter.

Udobang said: “It [the protests] was necessitated by the end SARS protests but I think that became like an umbrella for so many unjust things happening in the country.”

“I think [we are in] a kind of limbo period,” she said. “The protests were so hopeful. Everyone was going out every single day, people were donating food and money. It really was something where everyone felt like for the first time they could channel their energy towards something and we were all united for the first time in a very long time.”

Founded in 1992, the extra power given to SARS led to repeated incidents of police brutality and a unit that exercised fear over the civilians they were supposedly meant to protect.

Media freedom has been a notable victim of SARS brutality, with reporters repeatedly attacked and threatened by the unit. However, for a shift to take place, journalists must be protected. This, as well as being able to voice criticism towards the authorities, will be key to any kind of movement that brings about change.

“I think the role of journalists is incredibly important now,” noted Udobang. “This protest was happening during a global pandemic. A lot of the images shared were coming from Nigerians themselves. So the importance of documenting change, movements and what was essentially a massacre. The government did not acknowledge it.”

The country sits 115th in the World Press Freedom Index. Press freedom protection organisation Reporters Without Borders describe why Nigeria is so low down the rankings.

“Nigeria is now one of West Africa’s most dangerous and difficult countries for journalists, who are often spied on, attacked, arbitrarily arrested or even killed,” they said.

“The defence of quality journalism and the protection of journalists are very far from being government priorities. With more than 100 independent newspapers, Africa’s most populous nation enjoys real media pluralism but covering stories involving politics, terrorism or financial embezzlement by the powerful is very problematic.”

“Journalists are often denied access to information by government officials, police and sometimes the public itself.”

While the true impact the protests have had on Nigeria and its institutions is currently unclear, the demonstrations seem like a turning point for people in the country. Let’s hope it leads to more freedoms.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”5641″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Oct 2020 | China, India, News and features, Pakistan

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The Indian government’s revocation of autonomy for Jammu and Kashmir has been a disaster for free speech.

In October 2019, Narendra Modi’s government rescinded article 370 of the Indian constitution which had given the region special autonomous status since 1954. The region is now run as two separate union territories – Ladakh, and Jammu and Kashmir.

Ever since its autonomy was curtailed, access to information for inhabitants has been greatly reduced.

Despite palpable risks to their safety, journalists in the disputed region have remained, but a lack of access to internet has hindered their progress.

Set in the Himalayas, the region is famously beautiful – often described as “heaven on Earth” – but this is in stark contrast to the fierce and often bloody dispute wracking Jammu and Kashmir.

As the situation worsens, we look back at pieces published in Index magazine and online exploring the impact the conflict has had on free speech, journalists and the people who call Kashmir their home.

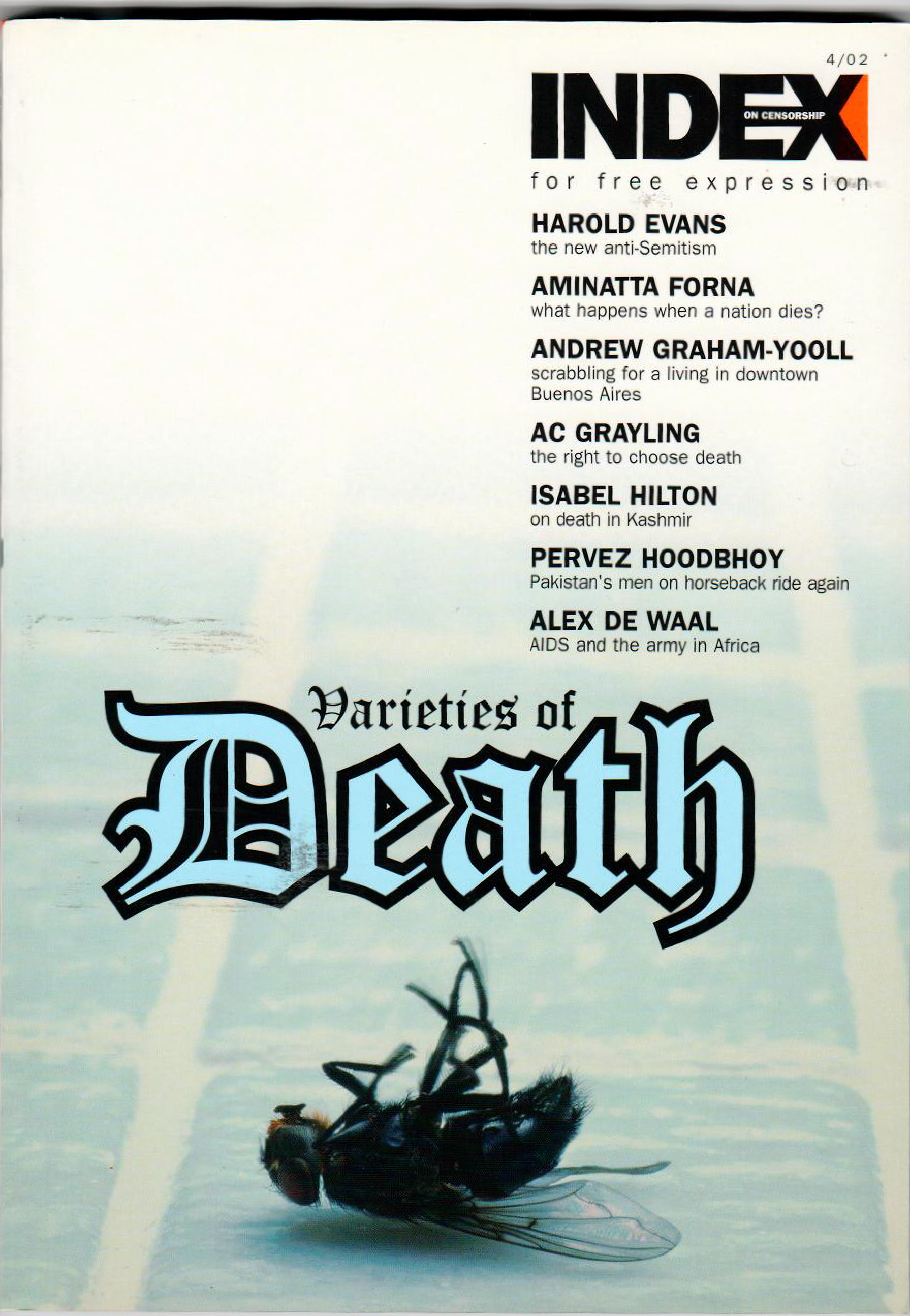

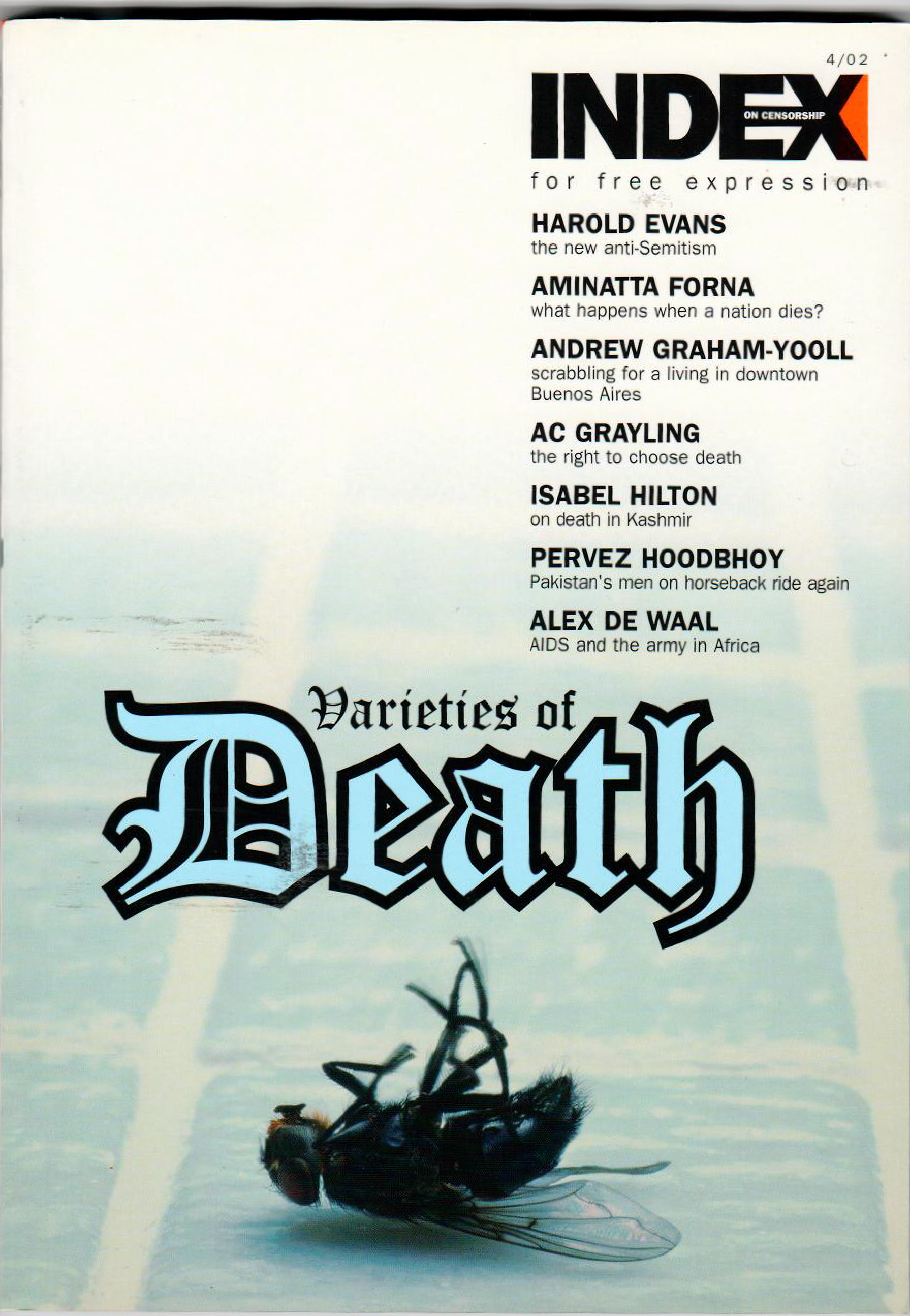

Varieties of death, the winter 2002 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Journalist and broadcaster Isabel Hilton visited Kashmir in the early 2000s. She documented her experiences in 2002 and spoke of her encounters with Pakistani military.

The piece is an insight into how much of major conflicts can seem underreported, but in fact are not. For journalists working in the region, the daily reports of death tolls and atrocities are both a livelihood and a duty, but only major events tend to make headline news across the world.

She wrote: “In Srinagar, the journalists — themselves constantly threatened and often attacked by both sides — have grown weary of looking for new angles on death. Only the larger outrages — such as the car bomb attack on Srinagar’s assembly building on 1 October last year which claimed more than 30 lives — are reported internationally.”

Index on Censorship autumn 2020 issue on the theme of the disappeared

In the most recent edition of Index (which can be read here), Bilal Ahmad Pandow discussed the experiences of journalists in Kashmir.

Since India took control and imposed direct rule, a feeling of (relative) security in the region has been lost and censorship laws have taken a firm grip, he writes.

A new policy for journalists introduced this year by the Jammu and Kashmir government imposes rules on restricting “fake news, plagiarism and unethical or anti-national content”.

“Pressure on media freedom was ratcheted up even further with the introduction of the New Media Policy 2020. Journalists were, of course, already operating under tremendous pressure – harassment, intimidation, the choking of advertisement revenue, imprisonment, draconian laws and a communication blockade – all of which are forcing journalists to self-censor.”

Index on Censorship summer 2020 issue on the theme of privacy

Earlier this year, Kashmiri journalist Bilal Hussain spoke with Index’s Orna Herr on life in the media in the region.

He told Herr of his personal struggles to get copy and videos past online restrictions and out of the country. Journalists have been creative in their attempts to get past the internet blocks designed to limit media freedom, he said.

“Since March 2020, the government allowed restricted internet access that blocked many news websites. So journalists installed VPNs that could break the firewall and enabled journalists to access those websites.”

“Some journalists used to travel to Delhi to access the internet and came back after filing their reports.”

“To get video interviews to my editor in Paris, I put them on a memory stick and gave it to a friend who was travelling to the USA, and he sent it on from there.”

Varieties of death, the winter 2002 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Poet Agha Shadid Ali was born in Kashmir in 1949. He moved to the USA in 1976 but his home was always at the forefront of his literary works.

His 1997 work Country Without a Post Office discussed the plight of Kashmir. At the time of their publication, he said: “My entire emotional and imaginative life began to revolve around the suffering of Kashmir.”

Ali died of brain cancer in 2001. Index included two of his poems following the 2002 Kaluchak massacre in which militants attacked a tourist bus, killing 31 people and injuring 47.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Media moguls & megalomania, the September 1994 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

This piece from 1994 by Caroline Moorehead shows how the human rights spotlight was finally being turned onto Jammu and Kashmir.

She writes: “In their war against the militants…the Indian police and security fores have come to treat disappearances with a combination of lethargy, obfuscation and threats, connived at by the judiciary. Court orders are ignored, relatives warned to stop making enquiries, and the case is shifted from place to place while documents are mislaid and those responsible posted to other places.”

It tells the story of the disappearance of 22-year-old Harjit Singh, a far from unusual story in the region.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Varieties of death, the winter 2002 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Beyond the Gun is a collection of photographs and statements from Kashmiri people in 2002. Its emotive language and testimony from residents who felt betrayed by India’s handling of the region, coupled with photographs of members of the community, make for a stirring read.

By Sheba Chhachhi, each photograph and collected testimony tells a different story. Some, like the words from carpet worker Jana, show the danger of bringing to light the problems caused by local authorities and provides a chilling account of escaping molestation by a border security force soldier.

Jana said: “I faced the power of his gun with the power of my mind. I felt no fear. I had the axe. Had the axe not been there; there was a rolling pin, a ladle. If I had a gun, they would have seized it long ago. These are my own implements. No one can take them away from me.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Partition, the November 1997 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

In 1997, Pakistan and India celebrated 50 years of independence, but continuing tensions between the two muted the festivities.

In this article from that year, Eqbal Ahmad set out the problems caused by a misguided approach to decolonisation by the United Kingdom, which led to the partition of Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Though not specifically about the troubles in Kashmir, much of the hostility between Pakistan and India is thoughtfully explained and ensures a greater understanding of the conflict.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Varieties of death, the winter 2002 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

In this 2002 article, Sidharth Bhatia claims India once had the world’s largest and freest media, something which has now changed. It takes a historical journey explaining chronologically just how India’s media freedom has been squeezed.

Bhathia ponders the problems populist jingoism can have on freedoms, citing the border war in 1999 as a prime example.

“More worrying is the decline in any challenge to the received wisdom on contentious issues such as human rights abuses, especially in Kashmir. This was seen at its most blatant during the border war at Kargil in 1999 between Indian and Pakistani soldiers (disguised as irregulars) who had infiltrated the area.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Feb 2013 | Uncategorized

Many, many things will be written about the papacy of Benedict XVI in the coming days (as a good summary of Ratzinger’s reign, I’d highly recommend this from John Hooper).

For me, it’s worth noting, briefly, Joseph Ratzinger’s historic association with Vatican censorship.

Previous to becoming Pope in 2005, Ratzinger had been head of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith — previously known as the Holy Office, and before that the Sacred Congregation of the Inquisition (bear with me).

The Holy Office had, in 1917, absorbed the Sacred Congregation of the Index. This was the body responsible for the maintenance of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum — the list of books and authors the Vatican prohibited Catholics from reading. This list, started after approval at the Council of Trent in the 16th century, contained authors from Giordano Bruno to Jean Paul Satre.

The Index was last updated in 1948. It’s very existence became an issue for debate during the discussions of the Second Vatican Council.

One of the main proponents of retaining the Index of banned books was Cardinal Frings, formerly the Archbishop of Cologne. Frings’s “Peritus” (theological consultant) during Vatican Two was Joseph Ratzinger. Frings and Ratzinger failed, and the Index Librorum Prohibitorum was abolished in 1966.

A few years later, when trying to think of a name for a new magazine documenting censorship around the world, poet Stephen Spender, journalist Michael Scammell and others settled, with an ironic nod to Rome, on “Index“.

And here we are today.