14 Oct 2022 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

Photo: Shima Abedinzade

I went on my first political demo when I was a baby – joining the march against pit closures. For four decades I have been on demos to save jobs; on pickets to support striking workers and; on marches against racism and political extremism. I have participated in political stunts at elections and vigils to mark horrendous and heartbreaking events. Each has been newsworthy to some extent, each was meant to be a mark of solidarity with a community or a group whose voice needed to be amplified in order to be heard. Each was a statement of my personal values and a commitment to make our society a little better.

But none of these acts of democratic participation required me to be brave. Not really. I never once considered if my political views could, on that day, cost me my life. Although in hindsight some of them made me very vulnerable. But I never thought about it seriously because I am so incredibly lucky to live in a democracy, to have basic human rights which protect my right to be heard, to protest, to assemble. To speak truth to power. My biggest threats came from individuals who wished me harm – not a government or a police force or a judiciary.

I am lucky. I know I am. And I am so grateful for it.

Which is why it is so important that people like me, like you, use their voices to promote those who are brave, those who risk everything by walking down the street without a head scarf, those who stage a sit in outside the Kremlin against an unjust war, those who unveil a banner exposing the tyrant that governs them. These people are brave beyond words. They use the only things available to them – usually their bodies – to challenge an unacceptable status quo. And by doing so they build a movement. They move the dial just a little and they place untold pressure on the tyrants and dictators who strive to silence them.

We have a duty to support them, to tell their stories and to amplify their voices. Because otherwise nothing changes.

The tyrants win if we let these acts of protest pass without notice. If we let global news move on and forget the faces of those who have paid the ultimate sacrifice to demand their access to the universal values that we hold so dear and so easily take for granted. We have an obligation to support the Iranian women in their demands for equality. We have a duty to tell the stories of those Russian dissidents who push back against Putin’s illegal invasion. We have a responsibility to ensure that the democracy campaigners imprisoned in Hong Kong are remembered. Not just today but every day.

We have to be, today and always, a Voice for the Persecuted.

28 Sep 2022 | News, Russia, United Kingdom

Dr Emma Briant, one of the key researchers who uncovered the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018

The vortex of misinformation, conspiracy theories, hatred and lies that we know as the unacceptable face of the internet has been well documented in recent years. Less well documented are the players behind these campaigns. But a small and growing group of journalists and researchers are working on shining a light on their activities. Dr Emma Briant is one of them. The professor, who is currently an associate at the Center for Financial Reporting and Accountability, University of Cambridge, is an internationally recognised expert who has researched information warfare and propaganda for nearly two decades. Her approach is that she doesn’t just research one party in the information war. Instead Briant considers each opponent, even those in democratic states, a breadth and detail that is important. As she tells me you miss half the story if you concentrate on single examples.

“This is a world in which there is an information war going on all sides and you can’t understand it without looking at all sides. There isn’t a binary of evil and pure. In order to understand how we can move forward in more ethical ways we need to understand the challenge that we are facing in our world of other actors who are trying to mislead us,” Briant says.

“There are powerful profit-making industries that are reshaping our world. We need to better research and understand that, to not simply expose some in isolated campaigns like they are just bad apples,” she adds.

Briant is perhaps best known for her work on Cambridge Analytica. She was central in exposing the data scandal related to the firm and Facebook at the time of the USA’s 2016 election. So what drove her to this area of research?

“My PhD looked at the war on terror and how the British and Americans were coordinating and developing their propaganda apparatus and strategies in response to changing media forms and changing warfare. Now that led me to meet Cambridge Analytica or rather its predecessor, the firm SCL group. Cambridge Analytica were using the kind of propaganda that had been used in the military, but in this case in elections, in democratic countries.”

The groundwork for this research was laid much earlier, when Briant lived as a child in Saudi Arabia around the time of the Gulf War. She was shocked to find lines and lines of Western newspapers censored with black pen, to the point you couldn’t read them, and pro-US and anti-Iraq propaganda everywhere.

“I was amazed by the efforts at social control,” she said.

Then, during her first degree, she studied international relations and politics when 9/11 happened and, as she says, “the world changed”.

“I was really very concerned about what we were being fed, about the spin of the Iraq war,” says Briant.

Like many she was inspired by a teacher, in her case Caroline Page.

“[Page] wrote a book on Vietnam and propaganda, and she had interviewed people in the American government and I was amazed that a woman could just go over to America and interview people in politics and in government and get really amazing interviews with high level officials. This really inspired me.”

Briant was motivated by both Page’s example and her specific work.

“She wanted to really find out what was going on and understand the actors behind the propaganda. And that is what really fascinates me most. Who’s behind the lies and the distortions? That’s why I’ve taken the approach that I have, both in looking at power in organisations like governments and how that’s deployed, and looking at how we can govern that power in democracies better.”

Because of Briant’s all-sided approach, she says she can attract the ire of people across the spectrum. People who focus only on Russia, for instance, might dislike that Briant critiques the British government. Conversely, people who are critics of the UK and US government call into question whether she should challenge Russian or Chinese propaganda. But, as she reiterates, “it’s really important to have researchers who are willing to take on that difficult issue of not only understanding a particular actor but understanding the conflict, protecting ordinary people and enabling them to have media they can trust and information online which is not deceptive.”

Criticism of her work has at times taken on a sinister edge. Briant is, sadly, no stranger to threats, trolling and other forms of online harassment.

“It’s very difficult to even just exist online if you’re doing powerful work, without getting trolled,” Briant says.

“The type of work that I do, which isn’t just analysing public media posts and how they spread, but is also looking at specific groups’ responsibilities and basically researching with a journalistic role in my research, that kind of thing tends to attract more harassment than just looking at online observable disinformation spread. Academics doing such work require support.”

Briant cites the case of Carole Cadwalladr, a journalist at the Guardian, as an example of how online campaigns are used to silence people. Like Briant, Cadwalladr pointed the looking glass at those behind the misinformation that spread in the lead-up to the EU referendum. Cadwalladr experienced extreme online harassment, as well as a lengthy and very expensive legal battle. Taken by Arron Banks, the case had all the hallmarks of being a SLAPP, a strategic lawsuit against public participation, namely, a lawsuit that has little to no legal merit. Its purpose is instead to silence the accused through draining them of emotional, physical and financial resources.

Briant has not been the subject of a SLAPP herself but has experienced other attempts to threaten, intimidate and silence her. Meanwhile, the threat of lawfare lingers in the background and has affected her work.

“Legal harassment has a real impact on what you feel like you are able to say. At one point after the Cambridge Analytica scandal it felt like I couldn’t work on highly sensitive work with a degree of privacy without the threat of being hacked or legal threats to obtain data or efforts to silence me. You cannot develop research on powerful actors and corrupt or deceptive activities as a journalist or a researcher without knowing your work is secure,” Briant says.

“Legal harassment has a real impact on what you feel like you are able to say. At one point after the Cambridge Analytica scandal it felt like I couldn’t work on highly sensitive work with a degree of privacy without the threat of being hacked or legal threats to obtain data or efforts to silence me. You cannot develop research on powerful actors and corrupt or deceptive activities as a journalist or a researcher without knowing your work is secure,” Briant says.

The ecosystem might be changing. New legislation has been proposed that will make using SLAPPs harder in the UK, where they are most common (the US, by comparison, has laws in place to limit them). But, as Briant highlights, there is more than one way to skin a cat.

“I don’t think people really understand the silencing effect of threat, not necessarily even receiving a letter but the potential of people to open up your private world. The exposure of journalism activities before an investigation is complete enables people to use partial information to misrepresent the activities, it can even put sources at risk,” she says.

While Briant believes these harassment campaigns can affect anyone doing the sort of work that she and Cadwalladr do, she says we can’t ignore the gender dynamic.

“Trolling and harassment affects a lot of different women and women are much more likely to experience this than men who are doing powerful work challenging people. This is just true. It’s been shown by Julie Posetti and her team, and it’s also the case if you look at other minorities or vulnerable communities.”

Of course if Briant was just a bit player people might not care as much. Instead, Briant has given testimony to the European Parliament and had her work discussed in US Congress. She’s written one book, co-authored another and has contributed to two major documentary films (one being the Oscar-shortlisted Netflix film The Great Hack). In today’s world, the attacks she has received have become part of the price people are paying for successful work. Still it’s an unacceptable price, one that we need to speak about more.

Briant is doing that, as well as more broadly carrying on with her research. She’s also writing her next two books, one of which revisits Cambridge Analytica. In Briant fashion, it places the company in a wider context.

“I’m looking at different organisations and discussing the transformation of the influence industry. This is really a very new phenomenon. Digital influence mercenaries are being deployed in our elections and are shaping our world.”

16 Sep 2022 | Belarus, Brazil, China, Iran, North Korea, Opinion, Russia, Ruth's blog, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is in a period of national mourning, marking the passing of our head of state, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Global media has been transfixed, reporting on the minutiae of every aspect of the ascension of the new monarch and the commemoration of our former head of state. While the pageantry has been consuming, the constitutional process addictive (yes I am an addict) and the public grief tangible – the traditions and formalities have also highlighted challenges in British and global society – especially with regards to freedom of expression.

We have witnessed people being arrested for protesting against the monarchy. While the protests could be considered distasteful – I certainly think they are – that doesn’t mean that they are illegal and that the police should move against them. Public protest is a legitimate campaigning tool and is protected in British law. As ever, no one has the right not to be offended. And protest is, by its very nature, disruptive, challenging and typically at odds with the status quo. It is therefore all the more important that the right to peacefully protest is protected.

While I was appalled to see the arrests, I have been heartened in recent days at the almost universal condemnation of the actions of the police and the statements of support for freedom of expression and protest in the UK, from across the political system.

What this chapter has confirmed is that democracies, great and small, need to be constantly vigilant against threats to our core human rights which can so easily be undermined. This week our right to freedom of expression and the right to protest was threatened and the immediate response was a universal defence. Something we should cherish and celebrate because it won’t be long before we need to utilise our collective rights to free speech – again.

Which brings me onto the need to protest and what that can look like, even on the bleakest of days. On Monday, the largest state funeral of my lifetime is being held in London. Over 2,000 dignitaries are expected to attend the funeral of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, in Westminster Abbey. The heads of state of Russia, Belarus, Afghanistan, Syria, Venezuela and Myanmar were not invited given current diplomatic “tensions”. While I completely welcome their exclusion from the global club of acceptability, it does highlight who was deemed acceptable to invite.

Representatives from China, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, North Korea and Sri Lanka will all be in attendance, all of whom have shown a complete disregard for some of the core human rights that so many of us hold dear. Can you imagine the conversation between Bolsonaro and Erdogan? Or the ambassador to Iran and the vice president of China?

While I truly believe that no one should picket a funeral – the very idea is abhorrent to me – that doesn’t mean that there are no other ways of protesting against the actions of repressive regimes and their leadership, who will be in the UK in the coming days. In fact the British Parliament has shown us the way – by banning representatives of the Chinese Communist Party from attending the lying in state of Her Majesty – as a protest at the sanctions currently imposed on British parliamentarians for their exposure of the acts of genocide happening against the Uyghur population in Xinjiang province. This was absolutely the right thing to do and I applaud the Speaker of the House of Commons, Rt Hon Lindsay Hoyle MP, for taking such a stance.

Effective protest needs to be imaginative, relevant and take people with you – highlighting the core values that we share and why others are a threat to them. It can be private or public. It can tell a story or mark a moment. But ultimately successful protests can lead to real change. Even if it takes decades. Which is why we will defend, cherish and promote the right to protest and the right to freedom of expression in every corner of the planet, as a real vehicle for delivering progressive change.

2 Sep 2022 | Opinion, Russia, Ruth's blog

Mikhail Gorbachev in 2008. The former president of the Soviet Union passed away on 30 August. Credit: European Parliament

In every field there are people who become living legends, people who inspire their colleagues and shape their chosen field. They add to our collective knowledge, they shape the world we live in and their contributions ensure that we both question the status-quo and think again about our individual and collective core values.

Sometimes these people reach further than their own fields. Sometimes they inspire or challenge the world. Whether as thinkers, writers or leaders. Sometimes their experiences and their contributions come to define an era of history – for some maybe even just one year.

1989. A year of deep turmoil. A year that reshaped the world. A year that defined the next generation. A year of both hope and horror. And on a personal level, a year that defined the type of world that I was going to live in.

1989 saw the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Tiananmen Square protests, the Velvet Revolution, the Hillsborough disaster, the Exxon Valdez spill, Solidarity was elected in Poland, FW de Klerk was elected in South Africa, Sky TV was launched and the Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Salman Rushdie. In different ways each of these events shaped the world we live in today – 33 years later.

I often write that there has been too much news. Too many issues for the Index team to cover. Too many crises. In 1989 we published nine editions of the magazine, to keep up with the news and to ensure that voices of dissidents were being heard, as authoritarian regimes began to fall.

In the last month I have found myself thinking a great deal about the events of 1989 and what they led to. The path of history that was chosen on those pivotal days and the actions of our leaders whose immediate responses to these events had long-term consequences. Whilst there are many global figures who dominated the news during my childhood, two of them have this month caused me to pause and consider what the world would have been like if they hadn’t been brave enough to challenge the status quo.

Sir Salman Rushdie and Mikhail Gorbachev.

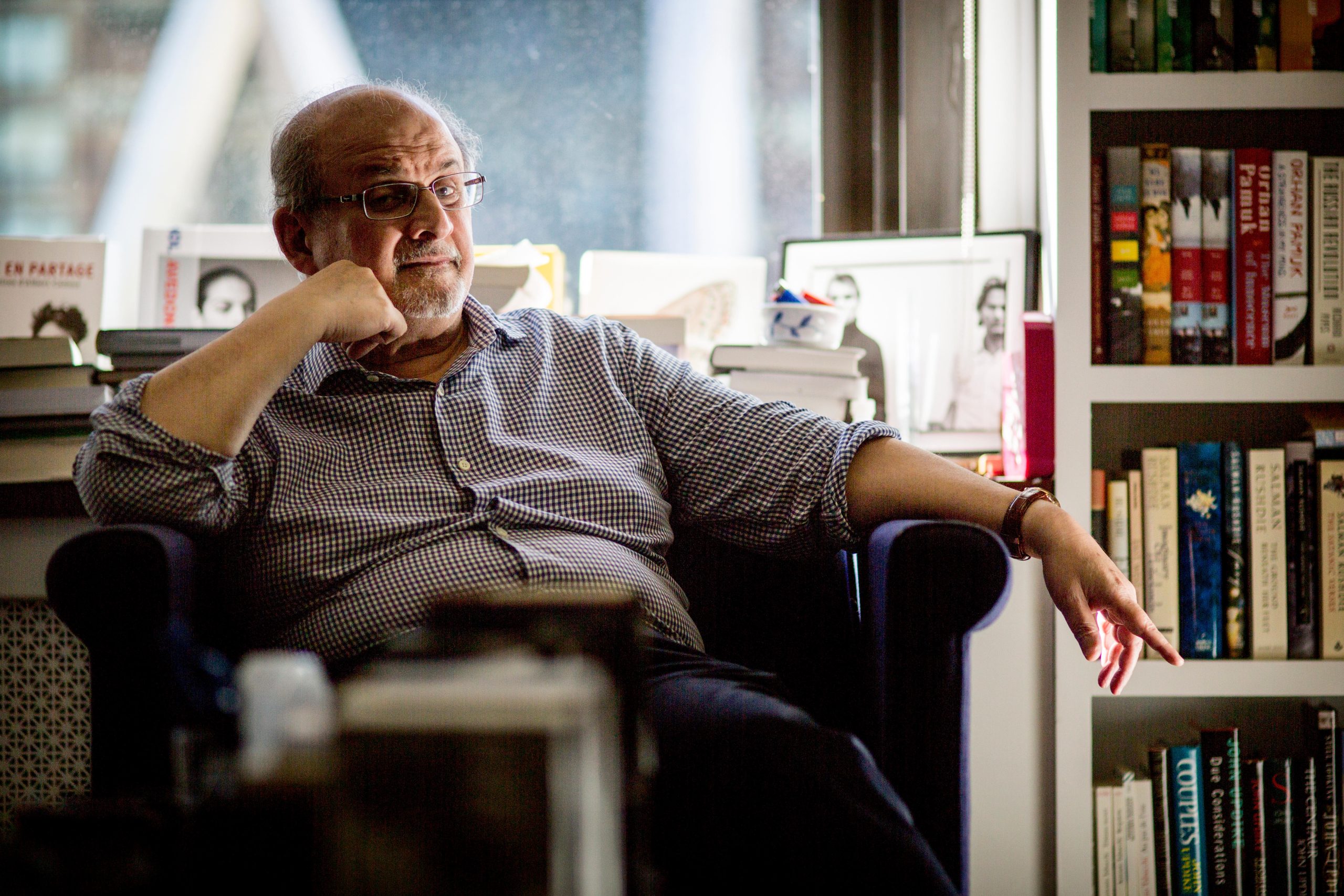

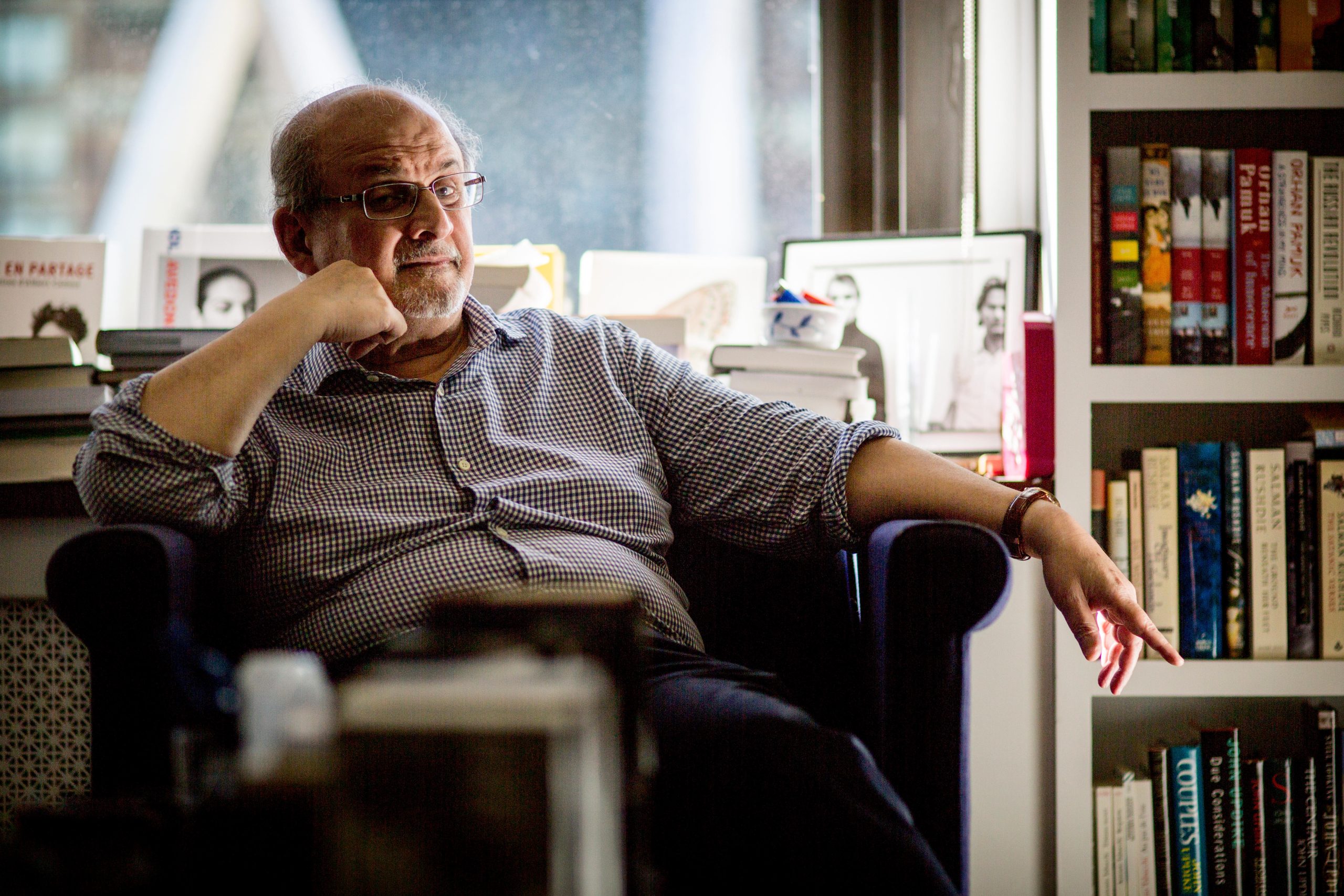

Salman Rushdie pictured in New York in 2016. Credit: Orjan Ellingvag/Alamy

Every day since the horrendous attack on Sir Salman, last month, Index has received messages of support for him as he recovers from his injuries. The messages have been touching, political and occasionally controversial – just like his writings! What they have demonstrated is regardless of people’s associations with him and their feelings towards him, his bravery and commitment to the values of freedom of expression in the face of the gravest of threats inspired a generation.

For over three decades he has refused to be intimidated, to be cowed. He continued to write, to speak and stay true to his values. He embodies the fight of the dissident, the determination to be heard and the power of words. He has shaped my approach to the world we live in and more importantly he has provided a role model for all of those that Index seeks to support and promote every day. I am so pleased that those who sought to assassinate him failed and we still have him amongst us.

In a different way Mikhail Gorbachev is just as fundamental to the history of Index. I’m not sure that Michael Scammell, the first editor of Index, would have believed that within a decade of Gorbachev’s coming to power in the USSR his writing would be in Index. His bravery in embracing glasnost provided hope for a generation.

The fall of the Berlin Wall without military repercussions provided hope of a peaceful transition to democracy – not just in central and eastern Europe but throughout the world.

This isn’t to say he wasn’t flawed. He was and his actions in the Baltics and the Caucuses were as expected from an authoritarian leader, and his support for the 2014 annexation of Crimea will forever tarnish his legacy.

But… Index was founded to provide a platform for samizdat, to provide a voice for dissidents who lived behind the Iron Curtain, to campaign for the right to freedom of expression both in the USSR and around the world. His bravery in embracing glasnost provided space for people to speak freely, to write and to be heard, even if Putin once again has shut the door. Gorbachev enabled people to get a taste of what they were missing. We can only hope that in the long arch of history glasnost will win out.

“Legal harassment has a real impact on what you feel like you are able to say. At one point after the Cambridge Analytica scandal it felt like I couldn’t work on highly sensitive work with a degree of privacy without the threat of being hacked or legal threats to obtain data or efforts to silence me. You cannot develop research on powerful actors and corrupt or deceptive activities as a journalist or a researcher without knowing your work is secure,” Briant says.

“Legal harassment has a real impact on what you feel like you are able to say. At one point after the Cambridge Analytica scandal it felt like I couldn’t work on highly sensitive work with a degree of privacy without the threat of being hacked or legal threats to obtain data or efforts to silence me. You cannot develop research on powerful actors and corrupt or deceptive activities as a journalist or a researcher without knowing your work is secure,” Briant says.